Rocky Has The Greatest Training Montage Of All Time

What do we want out of a training montage?

I mean that question seriously. What, do movie viewers truly want out of a sequence where the main character improves, grows stronger, and collects a new set of skills in a matter of minutes as the magic of movie editing compresses hours (even days or weeks) of backbreaking, bone-crushing work into a few shots? If you were to quiz the pop culture zeitgeist at large, the answer would be clear: bombast. The big picture view of the training montage is one that is inherently silly, one that is easily parodied, one that suggests anyone can get better at anything as long as they have some great music and some rapid cuts of them leaping from one activity to another. Training montages are silly, pop culture tells us, and the zanier and wilder and bigger they are, the more we remember them.

But the beauty of the training montage in the original "Rocky," released in 1976 ahead of winning Best Picture at the Oscars and inspiring one of the greatest and most inconsistent franchises in all of moviedom, is that it's not silly at all. Sure, its very existence inspired later sequences of such excess that they tend to dominate the conversation, but a look back reveals something very special. The key to the training montage in "Rocky," the greatest training montage of all time, is not its excess. It's how low-key it is. How achievable it is. How grounded in character and story it is.

An invitation to pant and bleed

While Sylvester Stallone would take the "Rocky" series to levels of '80s excess worth exploring and celebrating in their own right with the sequels, he wasn't behind the camera for the debut entry. That responsibility was on the shoulders of director John G. Avildsen, who treats Stallone's script (and performance) with a low-key, gentle touch that wouldn't be seen in the series again until 2006's understated "Rocky Balboa." Before Rocky himself became a millionaire action hero capable of conquering the Soviet Union, he was just a good-hearted schlub, a bruiser with a heart of gold, a bit of a dummy who was so sweet that you couldn't help but like the big ol' lug. Rocky Balboa circa 1976 felt like a real human being, one who ran out of breath when he worked out, went home sore after a long day at the gym, and could barely afford to pay his rent.

The training montage in "Rocky" reflects this and builds on it. When we see Rocky train, we're not just outside spectators appreciating the grandiose irony of increasingly ridiculous acts of physical empowerment. We're invited to pant and bleed and feel the anguish of every step ... and the triumph of a task well-accomplished.

So how do Avildsen and Stallone pull this off? Why do you actually feel the training montage of "Rocky" when its many siblings and descendants ask you to view and admire (and often mock) from a distance? Look at where Avildsen puts the camera, how long editors Scott Conrad and Richard Halsey hold their cuts, and how Stallone, a few years before movie star ego would temporarily rob us of a humane and naturalistic performer, sells how much it all hurts.

Something spiritual

It's no accident that Avildsen, Conrad, and Halsey all won Oscars for their work on "Rocky." Avildsen's camera exists largely in medium and wide shots, showcasing not just Rocky himself, but his environment and his spectators (or often, lack thereof). It's not just a sequence of Rocky getting stronger, but a sequence of Rocky in his surroundings, making use of the oft-limited resources available to him.

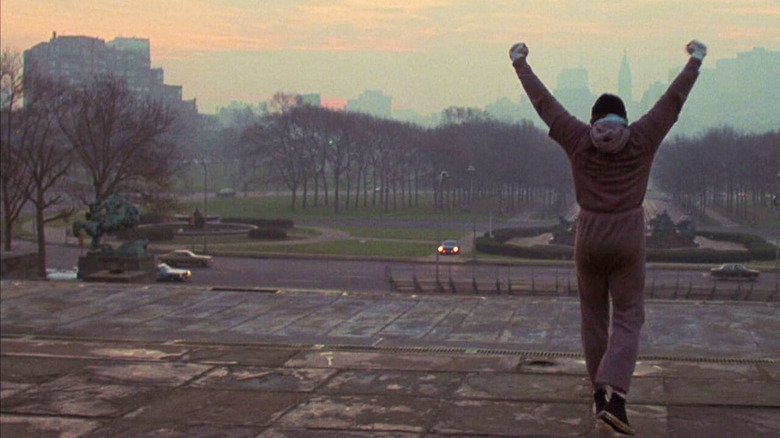

He pounds the pavement of Philadelphia (a city that looks like its crumbling at best through Avildsen's lens), jogging through a crowd that mostly ignores him — this is his fight, not theirs. He sprints down the docks, the only human being in the frame, a speck in the distance — his astonishing speed is for his own benefit, not the crowd. When he climbs those famous steps and raises his fists in the air, the camera retreats to a comfortable distance to showcase Rocky's victory — but also his isolation. He's alone as he celebrates, but it's still joyous and still feels like nothing less than a grand accomplishment.

Rocky did this for himself, and by emphasizing that the streets of Philly are largely neutral to his very existence — that he's not drawing a crowd, that Rocky and only Rocky can celebrate what he's done here — Avildsen transforms the character's journey up those steps into something spiritual. He's done it. No one saw him do it, but he did it. And Rocky, who just wants to go the distance, needs nothing more than that.

Bill Conti's soaring, iconic score explodes out of the gray visuals, lending Rocky's backbreaking training the transcendence one can only feel when they've accomplished a grand task and the only reward is your own satisfaction.

The invisible spectators

Through it all, Stallone looks tired. He looks spent. He looks like he's going through hell. Find the pain in his face as he tries a little bit harder. See the concentration in his eyes as he punches the meat and performs one-armed push-ups. This is Rocky Balboa the man, not the icon, and everything hurts. Unlike the superheroics of the sequels, we can actually fathom the pain Rocky is feeling as prepares. The audience doesn't know what it's like to lug trees in the Russian wilderness, like in "Rocky IV," but we sure as hell know what it's like to feel our lungs burn as we climb a flight of stairs. Stallone's willingness to allow Rocky to look vulnerable in this training montage is key — we can understand and feel the accomplishment like we rarely do with other movies.

Conrad and Halsey's editing, which holds on shots for far longer than you see in other training montages, allows the performance to sing. It allows Avildsen's framing to really hit home. The pain, the isolation, the loneliness, the triumph — it works because the sequence is cut to maximize the sheer difficulty of it all. Only that soundtrack works in a different step, but it's all by design. Conti's score draws the internal majesty of a hard-fought battle to the surface, while the filmmaking emphasizes the external pains and anguishes.

The training montage in "Rocky" is the greatest of all time because it's the rare example of the form to put character first, to ask us to empathize with the person growing stronger rather than to be in awe of them. Every choice made is built around this core idea: Rocky has to work hard, and we're going to feel it. And that makes Rocky's triumph our triumph, as the invisible spectators who cheer him on when he scales those empty steps. He doesn't know we're rooting for him, but we are.