How Skinamarink Uses Television To Put You In The Mindset Of A Child

This post contains spoilers for "Skinamarink."

Kyle Edward Ball's "Skinamarink" has become an indie horror phenomenon. For those who need catching up, the micro-budget film was financed via GoFundMe and was shot in Ball's childhood home for a thin $15,000 budget. It initially premiered at the Fantasia Film Festival in 2022, but soon after, the film leaked on the internet after a digital festival screening and became a viral sensation. "Skinamarink" was soon spread all over YouTube and TikTok; the grainy found footage video aesthetic made it an interesting and horrifying watch for those locked in their houses during COVID-19. This month, the film has been enjoying a successful limited theatrical run before it launches on Shudder on February 2nd.

"Skinamarink" follows two children who wake up in the middle of the night to find out that their parents have gone missing. Not only that, but all the doors and windows in their house are starting to vanish. To cope with the darkness and dead silence, the siblings decide to bring all their toys and blankets downstairs to commune near the television, playing tapes of cartoons on repeat to drown out the bumps in the night. Soon, it becomes clear that these children are not alone, that there's someone — or something – that lurks within their home.

Ball's feature-length debut is an experiment in analog horror, tapping right into the specific fears and paranoias some of us have experienced as children alone in the dark, begging the audience for their full attention and immersion into its crunchy, digital aesthetics. In my case, I found "Skinamarink" to be a movie about the act of watching movies as a child, and what happens when a young, active imagination learns to perceive the world through the act of consumption.

Obsession turned into consumption

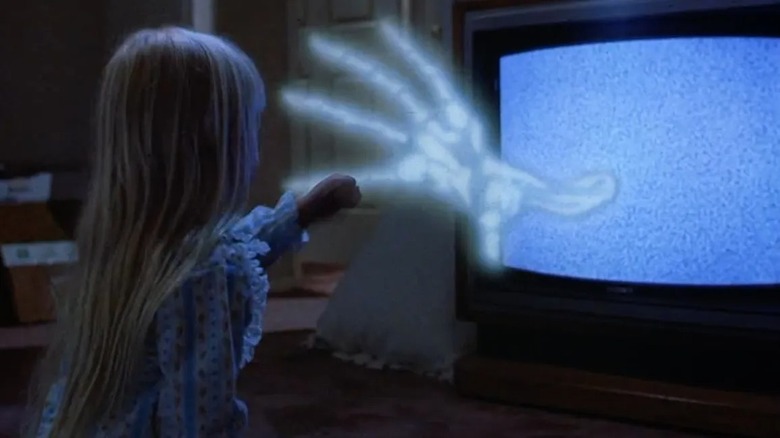

There's a famous horror motif that conjured in my mind as I watched Kevin (Lucas Paul) and Kayle (Dali Rose Tetreault) escape from their material danger into the safety of their zany cartoons. I immediately thought of 1982's "Poltergeist," specifically the image of a young Carol Anne (Heather O'Rourke) pressing herself up against the screen of a TV set. The way the bright light seems to radiate around her, overtaking her physical outline. I think of the opening images of the film, how the blurry shapes that make up The White House and Lincoln Memorial become distorted and warped into static nothingness, with which Carol Anne becomes fascinated. Peering into a void, her festering obsession with the TV set enables the angry spirits in her home to whisk her away from her family.

In both movies, there's a striking sense of comfort that the TV provides for these children. In "Poltergeist," which takes place in the mundanity of a Reagan-era Californian suburb, Carol Anne is drawn to the voices that emanate from the set that only she can hear. In "Skinamarink," the TV becomes the one and only source of light in the entire film. When you're a kid waking up in the haunting hours of the night and your parents are asleep or far away from home, what else is there to do besides succumb to images and sounds coming from the TV?

Ball's use of public domain cartoons seems thematically purposeful (and just downright creepy), but also evokes vague memories of childhood programming that feel imprinted on one's mind as they begin to loop and distort.

Retraumatizing the inner child

"Skinamarink" is a unique film in that the horror it evokes is subjective and doesn't seem to work on everyone. Depending on who you ask, it's one of the scariest films of the year, or it's just a glorified clip-show of walls and ambient noise. In my view, the film is full of very specific triggers that speak to some of us who had very specific childhoods and hyperactive imaginations.

Growing up in a divorce-torn lower-class household, my parents were often at work. I spent many nights with just my siblings beside me, or unattended with just a TV to keep myself company. On one hand, this was a very beautiful start to my relationship with movies. As an introverted kid who often stayed at home, the media I engaged with as a child was my window into perceiving the world around me. My curiosity burned through our home video collection. On one hand, this can be a positive experience. I found escape, learned valuable morals, and gained an appreciation for art.

On the other hand, that specific relationship with media is haunting in its own way. While watching "Skinamarink," I found myself easily identifying with the specific kind of loneliness and fear evoked by the children. The emotions that the TV made me feel were powerful, far past my own comprehension. Sometimes, the images on the screen become a threat in their own right. Repetitious, unpleasant, and eerie. I felt the way I did when I watched "Ju-On" when I was way too young, or would switch to the news to hear about some crime or tragedy that I could barely understand. I was horrified to think that the screen that nurtures me could also strike genuine fear into my heart.

A movie about watching movies, but in a twisted way

This is the core fear "Skinamarink" successfully exploits: being a growing, ignorant child living through a profound change without having any of the language, tools, or experience to even express what's happening, or what's wrong with you. In a later part of the film, Kevin calls 911 to tell them that he "hurt himself," but when the operator asks him follow-up questions, he's unable to respond or elaborate. It's viscerally upsetting to listen to, because at this point, the film has already reduced you to your inner child.

Ball's film sacrifices traditional plot structure to portray a collection of these anxieties in vignettes. How long do we need to wait until our parents are home? What if Mom and Dad never come back? What do we do then? What if I go back upstairs to get my toys, and there's something there waiting for me?

When you're alone in the dark and you need to calm these adolescent thoughts down, all you can really do is drown them out with the noisy glow of the television. If you're lucky, it won't end up staring right back at you.