Escape From New York Ending Explained: Bandstand Boogie Apocalypse

Snake Plissken doesn't give a damn.

When audiences see a bitter or misanthropic character in a movie, optimism likely leads them to search for the disappointed idealist underneath. One example: Rick (Humphrey Bogart) from "Casablanca." Rick is bitter and cynical about the world and doesn't care when scoundrels are taken away by the Nazis in Morocco. When Rick is asked about his nationality, he declares himself to be a drunkard. Audiences, however, will eventually learn that Rick lost his idealism years earlier when an affair with his ex-lover Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman) was cut off abruptly. Rick will eventually find a new lease on life by helping Ilsa out of the country, grateful for the time they spent together. "We'll always have Paris," he says wistfully.

Imagine an ending where Rick did not help Ilsa, and she was apprehended by the Nazis while Rick stood idly by, indifferent to her fate. That kind of bitter nihilism would have made "Casablanca" into a very different film indeed. Not a bad ending, necessarily — it would certainly appeal to cynics — but definitely a sour one. One that would perhaps have prevented "Casablanca" from becoming the enduring, celebrated film it is today.

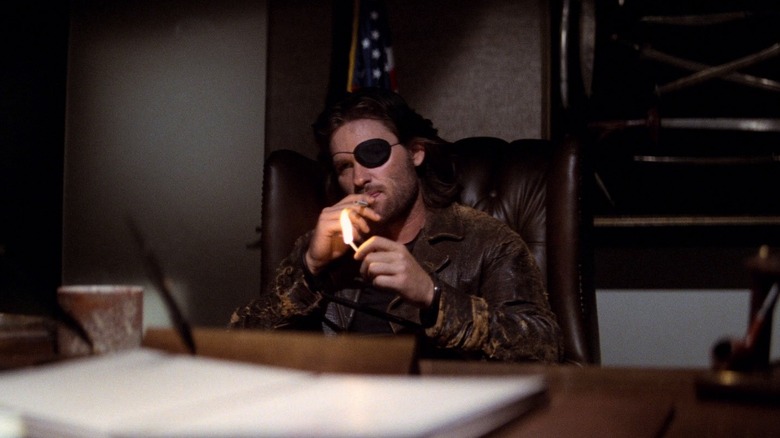

As such, an average filmgoer might be tempted to look inside Snake Plissken (Kurt Russell), the protagonist of John Carpenter's dystopian 1981 sci-fi film "Escape from New York," and seek the optimist lurking inside him. One will be sorely disappointed. Snake Plissken could care less if the world were to burn down around him. When presented with the opportunity to aid the world, Snake not only refuses but deliberately stymies the effort. Snake is a classic antihero in the Man-with-No-Name mold, complete with bitter stoicism, but without warmth or compassion.

In short, he's really f*****' cool.

Snake Plissken doesn't give a damn

Snake Plissken is, of course, an archetype. The stoic, uncaring antihero is a character that can be found throughout the history of literature. Indeed, as flip indifference came to represent the modern notion of "cool," flip or blasé protagonists became more and more common. For many years — and still to this day — anti/heroic characters in fantastical fiction are often heard commenting wryly on their own strange situations, bored more than astonished. One might call the most recent iteration the "That Just Happened" phenomenon.

When writing Snake Plissken, John Carpenter and co-screenwriter Nick Castle were likely not reaching back to the origins of antiheroes, but to more recent iterations taken from the works of Sergio Leone. Plissken, with his growly voice, a permanent scowl, and propensity for violence, closely resembles several characters played by Clint Eastwood. Snake, however — coming into the world in 1981, a time of Reagan, nuclear fear, and punk rock dismissal of an increasingly conservative America — did not possess his uncaring nihilism as an effect or as a clever analysis of character types. He, and presumably Carpenter and Castle, seemed to come by their hatred of the world honestly.

The premise of "Escape from New York" seems to be a theoretical extrapolation of neo-fascist, right-wing policies in the early 1980s. Set in the future of 1997, crime has shot up in New York City by 400%. The government's solution was to simply build a massive wall around Manhattan, transforming the entire island into a giant, unsupervised prison. Food is dropped in occasionally, but anyone who gets too close to the wall from the inside will be shot by guards.

This is America, 1997

The president (Donald Pleasence) is flying over New York when his plane is attacked. The president escapes in a pod, lands in New York, and immediately goes missing. Snake Plissken, recently arrested for various crimes, is coerced by the police commissioner (Lee Van Cleef) into trekking into New York to retrieve the president and a cassette he possesses that might prevent war from breaking out Snake refuses until a time bomb is implanted in his neck. If he doesn't rescue the president in the next two days, his head will explode.

Snake, like John Carpenter, saw the bloviating politics of a foolish president as not worth saving. Carpenter famously ridiculed Reaganomics throughout his career. Look at the picture above and not the flag. Carpenter and Nick Castle's President John Harker in "Escape from New York" was a stand-in for the ineffectual president at the time, armed with nothing more than self-interest and florid language. His 1988 film "They Live" posited that advertising and '80s economics was secretly ruled by disguised aliens hellbent on brainwashing the human population. Even his killer car film "Christine" was about the dangers of conservative nostalgia. That film is about a haunted Plymouth Fury built in 1958 that infects the mind of a teenager in the 1980s. Looking back to a "more innocent" time reveals the demons that always lurked there.

Snake is coerced by a neo-fascist police state to rescue a president he doesn't care about. Notably, Snake has no solution for "fixing" the world. He doesn't want to end prisons, he doesn't team up with activists, and he doesn't ever talk about how much better things used to be. He has evolved to develop indifference as a survival trait. The human race would be better off with a lot less of it.

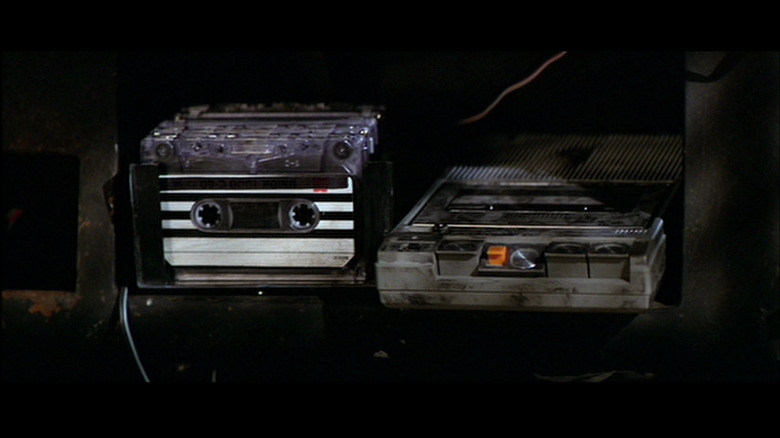

The cassette

With the nihilism of the hero firmly established, and the punk rock rejection of politics as presented by the filmmakers, we come to the end of "Escape from New York." In the film, the president is in possession of an audio cassette that contains nuclear secrets. This cassette must be played at an upcoming international summit to placate the planet's nuclear bomb-owning players. Snake barely escapes New York with the president in tow. Multiple compatriots that Snake met while inside are killed off by the gang leader the Duke (Isaac Hayes), an act of sacrifice that the president doesn't much acknowledge. Snake, perfunctorily, has the bomb in his neck defused just in time, and he is pardoned of all his past crimes. He is not relieved, so much as disgusted by the whole scenario.

Just in time, the president makes it to the political summit and prepares to play the nuclear cassette on the world stage. Out of the speakers comes "Bandstand Boogie," a song by Artie Shaw composed as the theme song for "American Bandstand" (1952-1989). Snake, it seems, swapped out the cassette for one belonging to the jovial Cabbie (Ernest Borgnine), a taxi driver he previously befriended. Snake walks away, casually ripping the magnetic strips out of the cassette, destroying it. Snake Plissken deliberately stymies peace talks, and may very well have put the world at risk merely to humiliate a terrible president. Audiences cheer.

Snake is a walking middle finger to the status quo. "Escape from New York" is a glorious, punk eff you to the politics of the world. Sometimes, one doesn't want diplomacy or solutions. Sometimes, one just wants to rip the guts out of the system in place. Snake, vicariously, does that for us.