The 10 Greatest John Carpenter Characters Ranked

Over the course of a filmmaking career that's spanned five decades, director John Carpenter has created some of the most memorable monsters in the history of cinema, including Michael Myers in "Halloween" in 1978 and the Thing in 1982. But Carpenter also has a knack for well-crafted characters, which makes sense when you consider that, much like Orson Welles and his Mercury Theatre company of players, Carpenter tends to draw from the same stable of actors for much of his casting.

As much as Carpenter enjoys working with well-recognized names like Donald Pleasence, Jamie Lee Curtis, and Kurt Russell (although it was his films that helped make the latter two known), he also has an affinity for promoting talented minority performers such as Keith David, Dennis Dun, and Victor Wong. Even a supporting player like Thomas G. Waites (Windows from "The Thing") has said of Carpenter, "He doesn't claim to be an actor's director, but he really is an actor's director. He really does care about the acting," so it makes sense that Carpenter would care enough to give his actors some great characters to play.

What follows are Carpenter's 10 greatest characters. Yes, "Big Trouble in Little China" and "Halloween" score two entries each on this list, and Kurt Russell alone plays three of these characters. Moreover, two characters on this list have proven so enduring that other filmmakers couldn't resist the temptation to pick up their stories and continue them.

10. David Lo Pan, Big Trouble in Little China

He's an ancient Chinese sorcerer who has to marry, then sacrifice, a green-eyed girl to regain a tangible, healthy body. His aspirations include ruling the universe. But what elevates David Lo Pan beyond an offensive "Yellow Peril" stereotype is his attitude toward the absurdity of the proceedings that surround him. Like Alan Rickman as Hans Gruber in "Die Hard," Lo Pan is a man with a plan that necessarily incurs collateral damage, but as far as he's concerned, he's done his homework, paid his dues, and earned what he sees as his inevitable victory. Then, all of a sudden, some rando interloper interrupts his long-awaited third act.

James Hong could imbue even cipher roles, like the Replicants' eye-maker in "Blade Runner," with a soulful humanity. Here, he makes Lo Pan's frustrations over having his schemes interfered with hilariously relatable, such as when he snarls, "You were not brought upon this world to 'get it,'" or when he sees our heroes' allies have arrived: "Now this really pisses me off to no end!"

And yet, Lo Pan utters a gleeful "Indeed!" when Jack Burton quotes his goals, because he briefly believes he's found someone else who "gets it." And when Jack notes that, after 2,000 years of searching for an eligible bride, "You must be doing something seriously wrong," Lo Pan chuckles about "the difficulties between men and women ... yet we all keep trying, like fools," assuming that his adversary understands.

9. Stevie Wayne, The Fog

She's the single mom and radio station DJ whose alluring voice bewitches the local weatherman and the fishermen at sea, but when the ghostly crew of the sunken ship Elizabeth Dane come calling with the fog to claim their vengeance on the coastal town of Antonio Bay, Stevie Wayne proves to be the heart and soul of the community.

"The Fog" casts top-flight actors like Janet Leigh and Hal Holbrook as the town's mayor and parish priest, respectively, but their characters' most effective crisis responses range from well-intentioned impotence to an alcoholic breakdown. It's the sexy DJ with the saucy asides who proves her mettle by standing her ground when the dead captain Blake and his crew start pounding on her door.

Adrienne Barbeau's acting talents have been frequently and unfairly dismissed over the years, but the role of Stevie Wayne affords her the range to display both empathetic panic, as when she pleads over the radio for someone to rescue her son from the fog, and steely resolve, like when she apologizes to her son over the air for not going to save him herself. Especially worth noting is Stevie Wayne's final speech to her listeners, telling the ships at sea, "Look for the fog," which parallels the ending of 1951's "The Thing From Another World," in which a radio reporter warns the world to "Keep watching the skies!"

8. Frank Armitage, They Live

"They Live" is not subtle about its politics. Its plot is that rich elites are literally zombie-faced aliens who use capitalism and mass media to enslave humanity, and it makes each of its three central characters the representative of a specific ethos. "Rowdy" Roddy Piper's John Nada is the reactive revolutionary, already accustomed to the world's economic inequities as a blue-collar drifter, but who is still so unprepared for how much worse the truth is that he reacts with impulsive outrage and violence. George "Buck" Flower, in his best-ever onscreen role, is a nameless homeless camp dweller who's collaborating with our planet's oppressors, and who can't betray his own kind fast enough once he sees the material benefits.

But Keith David is tasked with the toughest lift, and the most complex performance of the film, as Frank Armitage, the pragmatic realist who wants no part of this class warfare. As a Black man coping with the same economic struggles as Nada, Frank knows he'll suffer far worse consequences than Nada simply due to his race.

Carpenter's screenplay is deft and confident enough that it doesn't feel the need to spell out this intersectionality out loud, but it's why Frank keeps his head down and focuses on survival. At the same time, Frank is a giving, moral man, inviting Nada to his shantytown to get fed, handing him money after he becomes a fugitive, and joining his fight when he sees the face of their shared enemy.

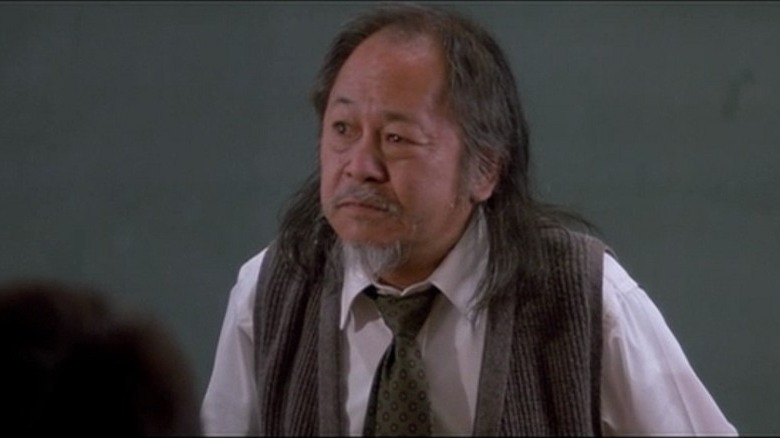

7. Prof. Howard Birack, Prince of Darkness

Who wouldn't want to sit in on a lecture by physics professor Howard Birack? Within a wild ride of a single minute, his opening speech to his students shatters their notions of "classical reality." As one student observes, "He wants philosophers, not scientists."

And yet, like British film and television writer Nigel Kneale's Bernard Quatermass — Carpenter wrote the screenplay for "Prince of Darkness" under the alias of "Martin Quatermass," and worked with Kneale on "Halloween 3" — Birack successfully roots out the scientific underpinnings of the seemingly supernatural. In a scene which sees Victor Wong hold his own with the formidable Donald Pleasence, Birack reconciles an old priest's religious faith with scientifically confirmed facts, positing the existence of a Satan who lurks in subatomic particles and a mirror-universe of antimatter.

Birack embodies all the characteristics of the best teachers; he's passionate about his field of expertise, he's able to articulate complex concepts in ways that even disinterested or inattentive students will find comprehensible and compelling, and he's wryly rueful enough toward his more underachieving students to make them want to do better ("Participating in this examination will greatly improve your classroom averages, I might add"). Plus, Birack takes his star pupils on extended sleepover trips to fascinating locations like creepy abandoned inner-city churches with impossibly old canisters of swirling green liquid in their basements. Granted, those excursions tend to have not-so-great mortality rates, but I've seen professors with worse reviews.

6. Jack Burton, Big Trouble in Little China

The greatest trick John Carpenter ever pulled on studio executives and moviegoing audiences was using Kurt Russell to sell them on "Big Trouble in Little China." While Russell's boastful, brawling Jack Burton is initially pitched as the film's protagonist, he's actually the Han Solo-esque sidekick in a mostly Asian "Star Wars," with his best friend Wang Chi (Carpenter favorite Dennis Dun) playing the role of a snarkier Luke Skywalker.

Russell underscores his character's white-guy arrogance by having Jack Burton habitually refer to himself in the third person, and even narrate his own supposed exploits over CB radio while driving his truck, complete with a full set of catchphrases he's obviously honed to sound cool. And yet, during the film's key fight sequences, Jack spends extended stretches of the action ignominiously sidelined by his own short-sightedness, knocking himself out with the falling rubble from his gunfire spray and pinning himself beneath the body of a vanquished minion.

Even when Jack strikes the killing blow against Lo Pan, it comes after an embarrassing fumble of a knife-throw, prompting Lo Pan to offer the sardonic compliment, "It's a good knife." Even so, it's easy to imagine an entire film series following Jack Burton's misadventures while driving the "Pork Chop Express," even if his role had remained that of the ignorant outsider who wanders into other people's epic sagas.

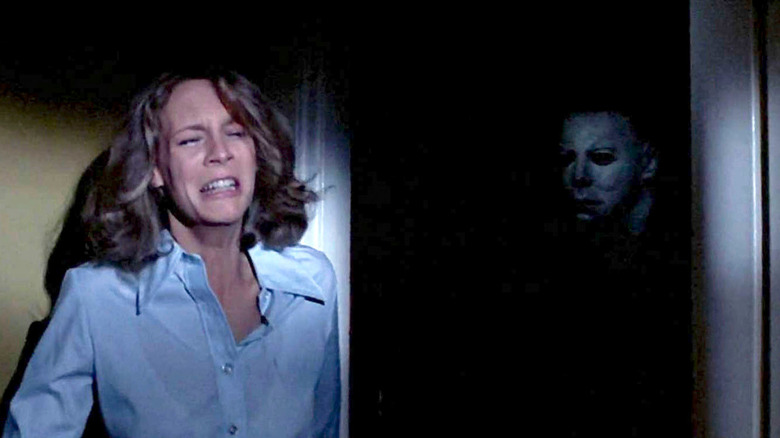

5. Laurie Strode, Halloween

Laurie Strode is horror's original "final girl," and thanks to the quirks of the "Halloween" franchise, we've been treated to a multiplicity of perspectives on how her adulthood turned out, à la Gwyneth Paltrow in 1998's "Sliding Doors."

What makes us root for Laurie Strode is how much she cares for others. Laurie not only empathizes with her friends over their troubles, but also covers for them so they can hook up with each other on Halloween night, as she earnestly seeks to assuage the fears of the kids she's babysitting about "the Boogeyman."

When Jamie Lee Curtis turned down "Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers" in 1988, Laurie Strode was killed in a car accident offscreen. But when Curtis signed up for "Halloween H20: 20 Years Later" in 1998, Laurie was established as having faked her death, changed her name, and taken a job as headmistress of the school attended by her teenage son. Outwardly, Laurie was a portrait of success, but her repressed PTSD drove her to drink, and when we saw her again in "Halloween: Resurrection" in 2002, her guilt over having accidentally killed a paramedic landed her in a sanitarium, where Michael Myers finally killed her.

The "Halloween" of 2018 erased the preceding sequels and presented Laurie as more openly traumatized — alcoholic, twice-divorced and estranged from her adult daughter — but also more empowered, having prepared for Michael's return by fortifying her house and undergoing combat training.

4. R.J. MacReady, The Thing

To survive an environment as harsh as Antarctica, you have to be already hardened by some tough experiences going in, and you have to be able to adapt to unexpected conditions as they change on the ground. This describes the Thing that crash-landed in Antarctica from outer space at least 100,000 years ago, and it also describes R.J. MacReady, helicopter pilot for U.S. outpost 31.

One of Kurt Russell's signature skills as an actor is his ability to turn his twinkling blue eyes ice-cold, and what makes MacReady a bit of an enigma is that you can't quite pin down how much of his ruthless survival instinct was developed before he set foot in Antarctica, and how much of it was honed by the unforgiving weather and isolation that's broken the psyches of his fellow outpost members.

Which is not to say that even someone as hardy as MacReady doesn't have his limits, as when he records a tape, in case no one at the outpost survives, and quietly confesses, "Nobody trusts anybody now, and we're all very tired," before he reconsiders this vulnerable admission and records over it. Because even before "The Thing" comes to their outpost, the researchers are all very tired, whether from watching tapes of game show episodes they've already seen, or from losing at chess to the computer (MacReady accuses it of cheating, right before he pours his drink into the computer tower).

3. Scott Hayden, Starman

"Shall I tell you what I find beautiful about you?" Jeff Bridges' alien visitor asks a SETI scientist, referring to humanity as a whole. "You are at your very best when things are worst."

Everyone forgets that John Carpenter made this film, because while the rest of his canon is typified by existentially harrowing revelations and a cowboy-noir rough-riding ethos, "Starman" is a heartbreaking, life-affirming elegy to grief itself.

In "Starman," Bridges plays an alien who crash-lands on Earth after interpreting the Voyager 2 space probe as an invitation, uses a dead man's DNA to clone a human body for himself, then coerces the man's widow into taking him on a road trip to the site where his people will pick him up. Bridges conveys the sense of an alien piloting a human body by adopting an awkwardly birdlike gait and a halting yet melodic cadence to his speech, cocking his head inquisitively and attempting to mimic the accents and hand gestures of the strange beings whom he finds so fascinating.

As "Scott Hayden," the Starman discovers love with the still-bereft Jenny Hayden (a movingly wounded Karen Allen) and helps her heal from her loss, all while basking in the beautiful, ridiculous diversity of the human race. "We are very civilized, but we have lost something, I think," the Starman says of his people. "You are all so much alive, all so different. I will miss the cooks, and the singing, and the dancing. And the eating!"

2. S.D. "Snake" Plissken, Escape From New York and Escape From L.A.

If Kurt Russell's stare is chilling in "The Thing," it's downright reptilian as "Snake" Plissken. What could have remained a mere riff on Clint Eastwood's Man with No Name was distinguished by how Russell and Carpenter worked together and, occasionally, at cross-purposes to define the character. In the commentary for "Escape From New York," Carpenter touts what he sees as Snake's inherent sexual magnetism, while Russell explains how he intentionally played Snake as asexual, but both are true onscreen.

The deleted opening scene of "Escape From New York" shows Snake not even bothering to count the loot from his bank heist, because he trusts his robbery partner to split their take fairly. Beneath the mean hombre exterior, there's still a shred of the U.S. Army war hero who was awarded two Purple Hearts, and became the youngest man ever decorated by the president for bravery.

We're never told what turned a veritable Captain America into an unrepentant career criminal, but when you combine Snake's oft-touted Special Forces resume with news stories about Vietnam and Watergate predating 1981's "Escape From New York" by barely half a dozen years, one suspects Lt. Plissken saw something in the field of battle that permanently altered his worldview, beyond whatever injury left him with only one eye. As deceitful as Snake can be, he's nonetheless relatively reliable about honoring agreed-upon deals, even with former partners-in-crime who have double-crossed him.

1. Dr. Samuel J. Loomis, Halloween

For most folks, "evil" is abstract or metaphorical. For Dr. Sam Loomis, evil is real. It's a person, made of flesh and blood. It has a name, and it has a Shape.

In 1963, 6-year-old Michael Myers killed his sister, and Dr. Loomis spent the next eight years devoting all his skills as a credible psychiatrist to understanding why. As surely as Joe Chill's bullets killed part of Bruce Wayne with his parents, those eight years destroyed whoever Sam Loomis was before, because for the seven years that followed, it became his Ahab-like defining purpose to make sure Michael Myers would never be free again.

From the original "Halloween" through its sequels, this mission cost Loomis everything, including his professional reputation and his physical health. The scars from setting himself and Michael on fire in "Halloween 2" in 1981 are still visible on his face in "Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers" in 1988, and remain through "Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers" in 1995.

"Halloween 4" delivered the brutal double-punch of Loomis' greatest triumph and tragedy, as Michael Myers finally appeared to be dead, but his niece, Jamie Lloyd — while wearing a clown costume like the one Michael sported during his first kill — stabbed her foster mother. Loomis whips out his pistol without hesitation, and when the sheriff prevents him from shooting Jamie, he collapses into tears, utterly defeated by the realization that you can't stop The Shape.