Meet The Robinsons At 15: An Oral History Of Disney's Underrated Gem

Disney's post-Renaissance era was marked by frustration and internal strife: The films were less financially successful, the studio was suffering a creative identity crisis, morale had hit a new low, and questionable management was a constant issue. While DreamWorks and Pixar were on the rise, Walt Disney Animation was floundering. But even as the slump persisted, optimism bubbled under the surface in the form of Stephen Anderson's "Meet The Robinsons."

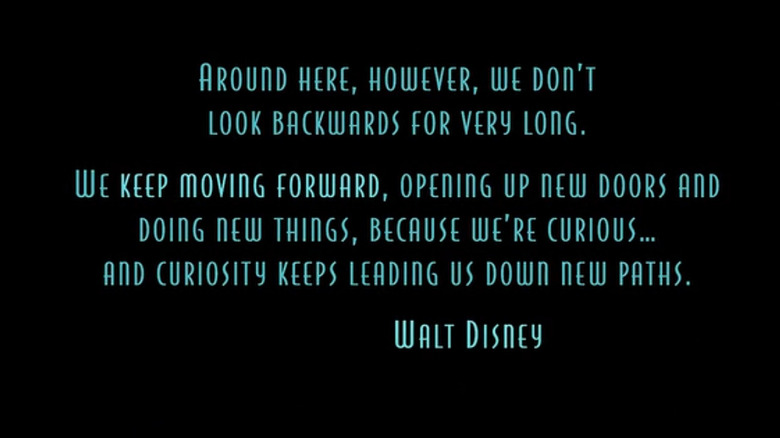

At the heart of "Meet The Robinsons," there's a very delicate balance between the past and the future. It's a fitting tension for a film that arrived just after the studio's golden era, but before its grand revival. As though blithely self-aware of its positioning, the movie begins with a logo that calls back to Steamboat Willie and ends with a powerful mantra from the man who started it all, Walt Disney. But the mantra in question warns the audience (and studio) away from dwelling in the past, calling us to stride towards the future with three simple words: Keep moving forward.

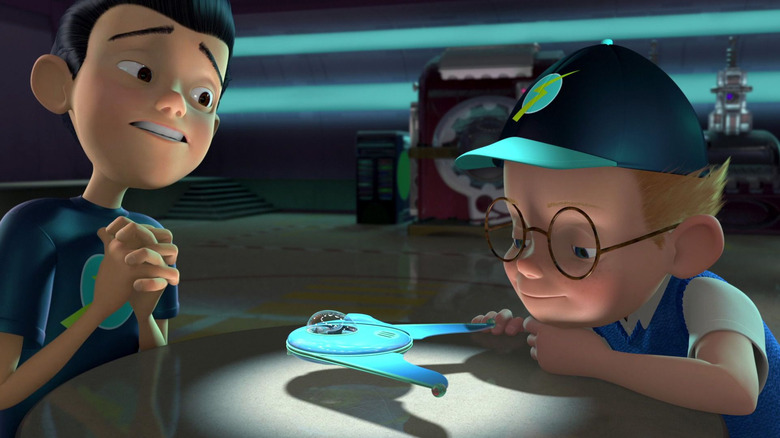

A Disney veteran who served as story supervisor for "Brother Bear" and "The Emperor's New Groove," Anderson chose "Meet The Robinsons" as his directorial debut, jumping at the chance to tell the story of Lewis, a young orphaned genius who makes a new friend, travels into the future, and defeats a villainous mustachioed man-child in a bowler hat. But most importantly, Lewis meets the surrogate family of his dreams — an imaginative, whimsical, weirdo bunch called the Robinsons. Space travel and singing frogs are their norm, a much preferable alternative to days in the quiet orphanage where he still hasn't been adopted. But jumping ahead to the future is no way to live your life. Before he wins his happy ending, Lewis must toil through his present. That's something he and the movie shared in common.

As the studio's second fully CGI-animated feature, "Meet The Robinsons" revolutionized how Disney rendered human characters and paved the way for more complex CG projects. But that doesn't mean the film had an easy journey to the big screen. It took over a decade before the draft first penned by William Joyce even gained traction. When at last production began, it was interrupted by one of the biggest turning points in Disney Animation's history: The acquisition of Pixar.

So how did the filmmakers cross the finish line? Below is the story of how "Meet The Robinsons" came to be, told 15 years after its release.

A Day With Wilbur Robinson

The story of "Meet The Robinsons" began in 1989 with a mere 32 pages. There was no orphanage, no bowler hat, and no mysterious connection between the two boys — just friendship, adventure, and a picture book called "A Day With Wilbur Robinson," written by acclaimed children's author, William Joyce.

Bill Borden (executive producer): The story of Wilbur Robinson is actually based on Bill [Joyce] growing up in Shreveport.

Willam Joyce (author, executive producer): When I was a kid, I had this friend who lived this very Gatsby-esque life. They lived in this huge, crazy mansion. It took up an entire city block in my hometown of Shreveport, Louisiana. And his family was wildly eccentric — as was mine, but in a much more middle-class way.

So the catalyst is Lewis comes in the gigantic front door and is greeted by this octopus named Lefty. And he walks in and there's Uncle Judlow shooting himself out of a cannon, and they're walking the tigers. And it's just presented so matter-of-factly because that's the way it was in real life. If I went over to Jan Parker's house, his mom would pick me up in her purple Lincoln Continental and she would drive up the purple driveway and open the purple gates, and we'd park next to the purple swimming pool. And their two standard poodles, which were dyed purple, would run up to us and greet us. And then we'd go in and get a snack in the purple kitchen.

And nobody said a word like, "Gee, isn't this neat," or "Wow, everything's purple," it just was the way things were. So I was like, "That'll be the fun, if these people do the most fantastic stuff, but it's what they do every day."

"Things are kind of boring here today," says Wilbur, "But we can't find grandfather's false teeth." And that's what they go looking for. That's the catalyst of everything in the story. Dinosaurs show up and time travel is used, epic pillow fights are had and songs are sung, and then the teeth are found and it's time to go home. It's all one day. And then our hero goes back to normal — whatever normal is. So that was the framework. That's how I came up with it.

Borden: I think Walt Disney would've loved Wilbur Robinson because [Bill Joyce] created a world and lived in it. He created the Robinson house, which was a magical place: A full-size train could come through the living room! A frog could sing! There was a frog band! Mom and the sisters wore these beautiful hats and sang! There was an adventure you could go on and find grandpa's teeth! For me, Wilbur Robinson is a story that is the perfect Disney story.

Joyce: The weird thing was, the book wasn't even published yet. But this producer [Bill Borden] was in my hometown making a movie. In fact, it was Reese Witherspoon's first film called "The Man in the Moon." We got to know each other and he saw the galleys and said, "I think this would make a great movie. What do you think?" And I go, "I agree." And he goes, "All right, I'll call some execs at Disney that I know. How long do you need?" I go, "I don't know." He goes, "Well, can you have it ready by Friday?" This was on Monday. So I worked up a treatment.

Borden: There was an executive at Disney, Bridget Johnson was her name. I called her up, I sent her the book, and I set up a meeting. Then we got on the phone and we pitched Wilbur Robinson as a live-action feature film.

Joyce: It was totally quiet. They didn't laugh at anything. They didn't ask any questions.

Borden: Bridget listened, was quiet, and said, "Thank you for the pitch." We hung up and I called Bill back. He said, "That didn't go very well. That was not very good."

Joyce: It was my first movie pitch. They just said, "Thank you," after I poured my heart and soul into this thing. [After] I hung up the phone, I was like, "That was so miserable. I'll never do that again."

Borden: Bridget called the next day and said, "Okay, we'll option it."

From live-action to animation

"A Day With Wilbur Robinson" went into development as a live-action feature. William Joyce was asked to pen the screenplay and landed on a story that closely resembled his book.

Borden: It started with a baseball flying over the fence. That's how Lewis meets Wilbur. He was playing baseball and he hit it over into the Robinson yard. He goes to get his baseball back and [ends up] on an adventure with Wilbur.

Joyce: They were bringing in things from the dinosaur era, but the crux of [the story] was not about time travel and adoption. It was about Lewis finding his way. It was also about how two friends helped each other find their place within their families. And it took place in one spectacular day.

But the project fell into "development hell." Joyce worked on various drafts, the script was passed around, and the live-action adaptation of "A Day With Wilbur Robinson" always felt on the verge of entering production, but never did. It even got to the point of courting big-name directors, including Peter Jackson and Francis Ford Coppola.

Joyce: I wanted George Miller or Steven Spielberg. I was aiming high. Miller hadn't done "Babe" yet, I don't believe. But god, "Thunder Dome" was so awesome and I was like, "This guy, he's a great stylist." That didn't get much traction. So then I started developing a film with Francis [Ford] Coppola, and I tried to get him interested in it. He was doing "Dracula" at the time and wanted to do "Pinocchio," so that's where his head was at. Then [future President of Buena Vista Motion Pictures Group] David Vogel came in, and Vogel tried to get Spielberg. It didn't happen.

That's when the Peter Jackson stuff was bandied about. He had just done "Heavenly Creatures." We [also] talked about Diane Keaton directing it, because she'd done a film called, "Unstrung Heroes," which is exquisite, and so seldom seen, and it just didn't succeed, and that kind of dashed that idea.

I was in Shreveport, Louisiana going back and forth, and new to the intrigues of Hollywood. You never know, until the papers get signed. There can be all the enthusiasm in the world. People will say such nice things — "Oh, he loved it" — but you don't know.

Borden: We took several stabs at a [live-action] feature film.

Joyce: I wrote 11 drafts. Maybe 12.

Borden: But the response that we got was, "Oh my God, how are we ever going to make this? It's too expensive. It's too big. Singing frogs? Spaceships?!"

Joyce: David Vogel was a mercurial head of Disney. And so I got the feeling after the Spielberg thing didn't pan out, it seemed to die. And in that way studios can be, when something dies for them, they just move on.

Borden: We tried and we tried and we tried for a few years. Then all went quiet.

Joyce: Things got quiet for a long time. And there was this exec at Disney named Leo Chu, who was a real fan of the project. I'm pretty sure that I'd gotten to know Leo, and I talked to him about how unhappy I was with just "Wilbur" not going anywhere. And he goes, "Well, let's try to bring it over here. Can you write me a letter explaining why you'd like to do it in animation so that I can show Tom [Schumacher, then President of Walt Disney Feature Animation]?" I did and it worked.

Leo and David Stainton, when he became Head of Animation, were really pushing it. And they were the guys who made it come together and start to actually become a film. I remember having this meeting ... they asked me to do a parade for Disney's California Adventure and I did the pitch for that with Michael Eisner [then CEO of The Walt Disney Company] and he said, "I'm very excited about Wilbur Robinson. I hear we're finally in production. How long has it been, like four years?" And I go, "11. It took 11 years."

Borden: It took on its own life. Once it fell into the animated world, Bill stepped up and did a lot of the designing. The script was developed a bit outside of my purview. It was like, "Oh, it's an animated film now. We'll produce it. We'll pay you. We're going to make a good movie." Disney is very proprietary about their in-house producing [and] at the time, I wasn't an in-house Disney producer. The longer it went on, the less involved I was. I was a producer getting scripts, but I wasn't that active.

A fresh take on the Robinsons

Just like that, development for "A Day with Wilbur Robinson" began anew. Disney Animation took over, with Dorothy McKim signing on as producer. A new script was penned by John Bernstein, fleshing out a grander story around the Lewis and Wilbur friendship: Lewis became an orphan and Wilbur became a time-traveler.

Borden: My one argument at the time was that I'm not a big fan of "Jimmy Neutron." I felt like it was stepping into the "Jimmy Neutron" world and not into the Bill Joyce world. They took it in a different direction than I would've taken it — let's put it that way. That was when I was like, "Okay, that's what you guys are going to do." They did a good job, but it wasn't the direction that I thought it should go. I made that clear.

Joyce: The one tonal difference that I missed was that [in my book] they played it so chill. I mean, this is how they live, this is what they do. They were much more like the family in "The Philadelphia Story," Katharine Hepburn's family. Just breezy and sophisticated and unflappable. And the Robinsons in the animated film are a little more goofy.

Borden: When you start creating time travel and meeting yourself, and the orphanage — it just took it in a direction that I didn't think was Joyce-ian. That's all. If you read all his books and if you know Bill Joyce, there's a youthful positive joyfulness about how his characters approach the world, which I love. I would love to live in that world. Jimmy Neutron's a different thing. Time travel and meeting yourself, that is just a different direction.

In 2002, Stephen Anderson had just wrapped up work as the story supervisor on "Brother Bear." Anderson knew he wanted to direct and even expressed that interest to Disney — but it was all about finding the right project. As if by fate, he was given a script that struck a very personal chord.

Stephen J. Anderson (writer/director, voice of Bowler Hat Guy): I was handed the script for this project called, "A Day With Wilbur Robinson." I knew that the studio had off-and-on been developing a take on the project over the years, but I had no knowledge of the specifics. So [Pam Coats], the head of development at the time, said, "Why don't you read this, and see if it's something you'd be interested in developing and possibly directing someday?"

I was immediately taken by it for all kinds of reasons. The number one reason being that I was adopted, so I completely understood this protagonist, Lewis. I completely understood his emotional state as a young boy, wondering where he came from and who his birth mother was. I had asked the same questions as a child.

The studio had no idea that I was adopted, it was a complete coincidence. So I went back and I said, "Yeah, you don't understand, I have to do this. I have to work on this project." So they said, "Great," and we started.

We assembled the story team. We brought in a different writer, a new writer, and then we had small editorial team, and we were writing, storyboarding, and building animatics throughout that year.

Robh Ruppel (art director): I started just by doing exploration: How could we take William Joyce's characters and make them animation friendly? He tends to draw these tiny little eyes that look great, but it's harder to get the acting out of that. So [I was] playing around with that and doing some very simple mock-ups. What does the robot look like? What does their house look like?

Anderson: I remember as a kid, if I read a book and then saw a movie adaptation of it, I always liked to be able to compare and contrast and see what was different, what was similar. I always thought it was neat if the filmmakers were able to find ways to connect back to the original source material. So I wanted to make sure that we were faithful to the book. And William Joyce [came on] as a consultant and an executive producer. We wanted to make sure we were honoring his original work, and that it was something that he could be proud and supportive of.

Joyce: All the elements of the finished film are pretty true to what was going on in the atmosphere of the live-action versions. And what I described as the plot from the live-action version was just the version we landed on, but we went through three or four. It's what made me realize that for an open-ended story, where the world-building is [already] done, the story was almost of no consequence. It was just an excuse for a series of tableaus. Then you have all the license in the world to prowl around in story possibilities.

Anderson: From a personal standpoint, I wanted to bring more of that adopted child perspective to the story. If I remember correctly, the first draft that I read talked about the adoption angle, but it was just a framework — the beginning and the end. I wanted to bring that to the forefront. So that was really what Lewis's emotional journey was throughout the story, was wanting to find somebody to connect to. Wanting to find someone who wanted him.

Storyboarding the way to success

Anderson: When I was handed that original script, they said, "If you're interested in doing this, we want to do something different than what we usually do with our movies. We want you to build a story team and an editorial team. You're going to storyboard the entire movie, all the way through. We'll put it up on an animatic, we'll screen it, and then we'll decide if we want to make it or not."

Ruppel: It was a thing [Disney] did at the time called the "Bake-Off," where everyone presents the things [that are] up next for production.

Mike Belzer (animation supervisor): That tended to be the launch to get people energized about a film, see what kind of pull it has to get talent to come over and say, "Yeah, I really want to work on this."

Anderson: There were two other movies that also screened their development screenings that same week. One was called "Gnomeo and Juliet," made by a different group of people [than the eventual 2011 version]. The other one was such a cool project that many people are sorry never saw the light of day. It was called "Fraidy Cat."

It was like a whodunit mystery with animals, with a cat as the main character. It was an homage to Alfred Hitchcock movies. So the cat was, let's say, like a Jimmy Stewart character in "Vertigo." It was very paranoid, witnessed a murder, and was trying to unspool what actually had happened. And it was done in a very Hitchcock-style noir-ish presentation in the boards. It would've been really great. I wish it could have been made, but unfortunately, it didn't make it.

Those other movies were not the whole movie. I think "Gnomeo" was the first act. I think "Fraidy Cat" was act one and act two. But I think that's only because we had been working a little bit longer on our reels.

Ruppel: Steve was the only one that had all three acts up.

Anderson: It was actually quite an anomaly at the time because the studio would storyboard things piecemeal, and you would just put parts of it on an animatic. Sometimes you'd start production before you had the whole thing storyboarded. So this was a really exciting opportunity.

The whole story team thought it was fantastic, because as a team, as storytellers, we [could] make our full statement. Say what we want to say all the way to the end. It was almost like "Hey, if they don't make it, we made the movie anyways." Because we got to tell the complete story.

Ruppel: It was rare, at that time, to have all three acts in ... All the other shows that presented had a first act and maybe a second act. They were still finding their legs. "Robinsons" was fully formed and ready to run.

Anderson: It was probably one of the most satisfying creative experiences I've had in my life, building that first version of the movie, because it was just nothing but pure, positive creativity.

During this development period, the bowler hat became a sentient henchman, Tom Selleck got a meta shoutout, Lewis accidentally turned his exhausted roommate Goob into a supervillain, and many of the film's most memorable gags were born.

Anderson: There's an illustration in the original book where the Robinsons are having dinner and they are shooting meatballs out of little cannons. So we had a dinner sequence in the film and it was storyboarded by an artist named Nathan Greno, who ended up directing "Tangled." We talked through how it needed to progress the story but then the specifics were just left up to Nathan. So he went away and just storyboarded a bunch of ideas. And we knew we wanted to pull some of the elements from the book into it. So the meatball thing was one of them, and he turned it into this ninja-movie type sequence.

A low point for Walt Disney Studios

Anderson: There were four films at that time that were being seen as the future of the studio. It was "Chicken Little," "Meet the Robinsons," "American Dog," [which was reworked into "Bolt"], and then a film called "Rapunzel Unbraided," which ultimately became "Tangled." But this version was more of a "Shrek"-type take on Rapunzel — it was more of an irreverent sort of fairytale parody. Those were the four big films.

That was 2003, so Walt Disney Feature Animation was pretty beaten down at that point. People were less and less interested in seeing our movies. Pixar was really growing. DreamWorks was really growing. Those studios were having huge success, while Disney was really struggling at the time. And there was a general feeling that all the best people had left Disney and went to Pixar or DreamWorks.

So while I'm not saying that our first screening was perfect or brilliant by any stretch of the imagination, it was a nice galvanizing moment for the studio. The cumulative effect of that week [of screenings] was a huge motivation boost for everybody there, because it felt like, "Okay, we have some fun, exciting projects in development, and we do have a bright future here at Disney. And there are still great people left at Disney — not everybody left." We were all really proud to be part of that moment [when] the studio came together and felt inspired again.

Belzer: Those [development screenings] always meet mixed reviews. But when Steve put together the pitch for this film and he put it to storyboard and had a screening of it ... I've never seen, and I'm sure others would agree, a film that well-received. People were just like, "This is amazing. This needs to be made now and don't change it, let's just animate it."

Mark Anthony Austin (animator): Normally, the initial screening is a great blueprint to work upon, and then you develop a story, and it gets stronger and stronger and stronger over time. But Steve Anderson's first version of the movie that he showed in storyboard frame was by far the movie we should have made.

Ruppel: It was the sharpest, the cleanest, the tightest. It was just like, "That's it. That's the one that's ready for production."

Austin: You'd have to have seen that first screening, but it wasn't just me. It was unanimous.

Anderson: A few people stood up and applauded at the end, which was really touching. [It was] probably one of the most euphoric days I've ever spent in my career.

Austin: Everybody that was in animation that wasn't an exec thought that we should have just made that first [version], without changing anything. Instead, it went through these rounds. Disney, when Walt was alive, Walt had the vision, and his vision got put up on the screen. In modern days, the director isn't given that kind of power. The director's vision is used as a starting place, and then [the movie] is made by committee. In "Meet the Robinsons'" case, the vision was perfect.

Welcome to a new era of animation

Of the three movies screened, "A Day With Wilbur Robinson" was chosen to move forward and officially began production in 2004, with its release scheduled for 2006. But it was not smooth sailing ahead. There were unexpected financial constraints to grapple with, and for some folks on the team, making a CGI-animated movie meant exploring brand new territory.

Anderson: Unbeknownst to us, we were already in a financial box before we got the green light. Whatever movie was going to go forward out of those screenings had to fit in a certain financial box and when we were boarding the movie, we were just trying to make the best movie we could. So we weren't trying to think about complexity, or how much something would cost, or how difficult it would be to produce. We were just thinking about the best movie. So when it came time to figure out how to make it, we realized, "Oh boy, we may have overshot the box that we're supposed to be in."

So in terms of financial issues and technology, we had to start figuring out, "Okay, how can we be smart? How can we be economical? How can we make this movie for a smart price?"

Adam Dykstra (animator): By the time the animation crew came in, they had already gotten pretty far with the story. We had all three acts boarded and everything up on the screen, at least in rough form.

Anderson: So we would do a new storyboard screening probably every three to four months, implementing notes and trying to make them better. And then began the process of building the sets, modeling the characters, trying to figure out the design philosophy — all that good stuff to get the production up on its feet.

Ruppel: So first you focus on getting all the designs ready for modeling. What does the classroom look like? What does the school auditorium look like? What does the memory machine look like? Once that's designed, it goes into modeling [and then] surfacing, which is texture, paint, and color. And then of course, the characters have to be modeled and rigged. They have to put a skeleton in them, so when they raise their arm, the shoulder crinkles appropriately. [Then] layout: Where's the character in the relationship to the camera? Do they cross screen left? Does she pick up something? Does the camera follow her? Do we cut to another scene? Once that's all set, we go into final layout and then lighting.

All the final stuff gets cut into the reels. So you always have screenings where you might have 50% rough animation, 50% storyboard. And then at some point it's 50% layout, 25% final layout, 10% color. So more and more of the shots get finished and come online. They get cut into the reel, to the point where you are starting to see the film evolve.

Anderson: There was a big learning curve for me, because my background was in traditional animation. So I had to, as quickly as possible, learn as much as possible about this new world of computer animation, so that we could bring that to life.

Belzer: "Chicken Little" was the first completely CG animated film [from Disney].

Dykstra: They trained a bunch of us to go from traditional animation to CG and we basically cut our teeth on "Chicken Little." And the next project up for CG was "Meet the Robinsons." That's how I got involved.

They decided to take a big group of us and they put us in a building. It was roughly about three days a week for six months in Glendale. We trained over there and then we would work on tests and assignments and then show them. And at the end of that training period, they would decide who was making the transition successfully. And some people who didn't might go into another division of animation, but generally speaking, most people were able to adapt and make it through the process.

Belzer: There was some fear involved, and understandably so.

Joyce: For people who had been in 2D, it was tough to make the transition. A quantum shift like that doesn't happen very often. Think about it: In the history of film, there was silent film and there was sound. There was black and white and then there was color. Those are the only things I can think of that were this pivotal. [With] computer animation, you can make an entire film with an entirely different set of tools. And I don't know when we'll ever see something shift like that again. Who would've thought, in 1950, there'd be this thing that you could make up a movie with?

Belzer: I always equate it to, when people say "Is 2D gone" or "Is 2D dead"? It's like, well, no, it's just a different art form. You don't throw out all the oil paintings because watercolor came along. There's certain principles that are in line with one another, but it's a very different process. And there's a number of individuals who came over from the 2D world to work in that realm, and they did very well. Others struggled.

Dykstra: The best description as an animator, it's like trying to draw with a 20-foot pencil at the beginning. You spend your whole career having the shortest distance from your brain to the paper and when you suddenly switch to CG, you've got a gazillion buttons to push and all these technical things to remember to accomplish the same task.

Anderson: My concern was that, as a director coming in and not really knowing anything about the technology, that I would be looked upon as, oh, this guy doesn't know what's doing. But everybody was so excited to help me learn what I needed to know to direct the project, and actually very respectful of the fact that I didn't know everything, but I wanted to learn. [They] were very willing teachers to me, and it was a great education in that new form of how to make animation.

Belzer: There's some directors you just remember. Steve was one of the best. I really loved working with Steve. He gave credit where credit was due and he let the people do their job. And that's often not the case with many directors that I've worked with over the years, where they try to stranglehold, "No, I want it done this way." Steve was genuinely curious. He'd listen and he'd accept ideas, but it was very clear, too, he was the director.

Finding the Robinson look

At this point, Disney Animation wasn't new to the world of CGI. Many Renaissance-era films made use of the technology (think the "Beauty and the Beast" ballroom scene or "The Lion King" stampede), and "Chicken Little" had earned the title of Disney's first full CGI release. But translating the Robinson story presented a new set of challenges because it sought to veer away from "cartoony" human characters.

Anderson: We did go through a bunch of different iterations of the style of the film. Questions being, do we want to make it look exactly like Bill Joyce's illustrations? Do we want to bring a little more of a Disney feel to it? Our character designer, Joe Moshier, his style is even a bit more cartoony than what the film actually ended up looking like, in a great way. Joe's an amazing designer. But he tends to be pushing shapes and proportions even more than what the average Disney film might do, and certainly what Bill Joyce's illustrations look like. So we had quite a range in there.

At the heart of it, it had a very heartfelt story about this boy looking for a place to belong. The look of it had to be grounded in some believability and reality so that you would feel those emotions. So we never wanted to go quite as cartoony as a "Chicken Little." There was a lot of research and development that had to be done there, which was later leveraged for subsequent films like "Tangled," "Wreck-It Ralph" and "Frozen." It was all part of development there at Disney.

Belzer: You look at something like "Toy Story," which was the first computer-generated film, and how it holds up to a computer-animated movie of today. The difference there being, they were smart in that the first CG-animated movie was [about] plastic toys. We wanted to push the envelope. We wanted human characters. And one of the challenges with a human character is that we are all humans and so whether you're an artist or not, you inherently know how a person might move or look. If you're watching a performance of a CG character [and] it doesn't move properly, you're going to feel it. You don't know necessarily why, but it's something that's just not right.

Think of a doll. If you just put your finger on that eyeball and you move it, the face doesn't move at all, but the eye rotates within it. And that's fine for a doll, but if it's trying to convince the audience that it's human, it looks a little creepy. So having the skin move a little with the eye helps tie in the realism. That's what animators do, right? We analyze movement.

It's like, "Well, how does that move? Why does it look that way?" As you're talking, the tip of your nose might be going up and down a little bit. It doesn't just stay rock solid. If it does, well, that's a stylistic choice, but it could look a little odd. So all these things had to be figured out and mapped out ahead of time.

Anderson: Bowler Hat Guy was a challenge, because at the time, computer animation in general didn't have quite the flexibility that it has now. We wanted to give him that slinky, snaky quality in some of the shots when he was being villainous. So that was a challenge, because you couldn't quite bend or break character rigs like that back then.

Belzer: The human characters wear clothing and the clothing was, for lack of a better term, stuck to their body. It's almost a rubber suit. So as a character might reach across themselves, the way your shirt is going to wrinkle, it didn't do that. It just sort of stretched as a piece of rubber might do, like a Spider-Man outfit or something. And that wasn't ideal-looking. We really pushed for cloth. We didn't win the battle, because it [would've been] too expensive to do too many cloth renders at that time.

Anderson: I look at something like "Hotel Transylvania" now, and those characters are just so rubbery, and cartoony, and it's great. I would have loved it if we had that ability back on "Meet the Robinsons," but it just wasn't quite there yet.

Enter the Pixar Brain Trust

Anderson: I'm going to guess it was maybe early 2006 that the title changed. It could have been late 2005, but the feeling was that maybe "A Day With Wilbur Robinson" was a little bit of a mouthful. We wanted to try to find something a little sharper.

We brainstormed a lot of titles. The one that I really liked was "Inventing Lewis," which I think was maybe a little too artsy-fartsy for the studio. Funny enough, I remember there was talk of calling it "Tomorrowland." Because we had the Tomorrowland/Todayland reference in there, and it's all about the future, and inspired by Walt Disney's vision of a positive future. But we really wanted to have the name Robinson in the title somehow — that was very important to everybody. So then "Meet the Robinsons" became the title.

Settling on a title was hardly the biggest development of 2006. This was also the year of Disney acquiring Pixar and shaking up management by putting then Pixar chief creative officer John Lasseter and president Ed Catmull in charge of Walt Disney Animation Studios.

Joyce: Every regime change is going to be tough. [Steve] started out with Schumacher, then came Stainton, and then Lasseter. Three captains. Three admirals. Three warlords.

Anderson: John and Pixar became part of Disney in early 2006, so we were probably two thirds of the way through the movie. I love their movies, and had huge respect and admiration for what they did. So I was very intimidated, and already pretty exhausted, having gone through about three years of not only the production, but also what I feel was, frankly, some not very solid leadership at Disney animation, prior to John coming in. Leadership that had their priorities a little out of wack [and] was more reactive to what other people and other movies were doing.

Austin: We were pumping out movies that weren't doing half as well as Pixar movies, and I think most of the problem was that Disney was still adamant that they were making movies the same way as they'd always made them, which was the classic way of making movies. But making a digital movie is a different approach to a classic movie. You have to approach it differently. It isn't the same medium, so the process is slightly different.

It took them a while to adjust from basically saying, "Don't tell us how to make movies, we're Disney!" to learning that, "Oh, there is another way to make CG movies, and it's this way." And Pixar had made that evolutionary step, but Disney hadn't. Pixar was on the fast track, looking at cinematography and making digital movies more like live-action movies, and Disney was still locked-off cameras.

Anderson: When John and the Pixar folks came in, I feel like I didn't quite have enough energy to really stand on my own two feet and kind of say, "Here's what we want to do," and push back a bit on some of the notes that I didn't always agree with.

Disney was at the bottom of the heap at the time. So there wasn't a lot of respect for what we were doing. I didn't feel like I had any creative leg to stand on, to talk to Pixar on their own level. So I think there were some things that I went [along] with that made the movie different — but maybe not better — that I wouldn't have done.

Belzer: Often when you have a film that's being created, you'll have periodic screenings and you'll get notes. I remember there was one on a different film [where] a very high-ranking person — it's hard to get a higher up ranking individual than this at Disney — was making calls to add a certain character or make changes based on just a whim of a feeling of what he might want to do.

A lot of thought has gone into why these characters are this way, their character arcs, how they're responding to one and another. It's a very complex puzzle that's being created. So arbitrarily throwing something out is pretty disheartening. But when you have a high-ranking person tell you something, often it has to be done.

But now, flash forward, here we are with Disney and John. He is the high-ranking official, but he is an animator, primarily. He came from being an animator and he knows film. He's a wonderful director. So getting notes from John was very different.

Anderson: It was an interesting situation because on the one hand, having John coming in to lead the studio was so much better for the creative process because he's actually a filmmaker. We knew we were going to be led by really good creative as opposed to the business first or marketing first of the previous leadership.

However, it was tough because we'd already had a lot of struggles getting the movie to that point in early 2006, when the leadership changed. Ultimately, I felt like a lot of us were just trying to protect the movie from ... I don't know what the right words are, but notes that were less about making it a better movie and notes that were more about, "How do we make it more commercial?"

I understand that there is a reality to the world and that Disney is a large company and that we do have to make money to keep making movies. But I think everybody's feeling was, "If you make the best possible movie, you will find the audience, you will get the people, you will get the box office." But sometimes it felt like it was a little bit backward, putting the cart before the horse a bit.

In which the Bowler Hat comes to life

Joyce: I've read a lot of stuff about how John came in and they threw out 50% of the movie, and that's just not true. But it was tough for a little while there. It wasn't the easiest way to finish a movie.

Anderson: I remember one comment being something to the effect of, "This is a great foundation. Now, how can you paint with a deeper brush? How can you deepen the emotion, deepen the stakes of the movie?" It stayed pretty light, that first version. We still had all the adoption stuff and the Bowler Hat Guy and all that, but there wasn't the evil future [and] there wasn't the dinosaur, the T-Rex character.

Belzer: [John] basically said there was one character aspect that had to be changed, and that was the villain, the Bowler Hat Guy. It was met with mixed emotions. Because, of course, you're close to what you've been working on for two years and now somebody's coming in and pulling the rug out and throwing away a lot of work. But he's making changes for what he feels are good reasons. Steve had to pivot and make some major adjustments with that character in order to lead him back into the story the way John [wanted]. And I think he pivoted really well.

Anderson: That was the big trigger that turned Doris into the main villain, like the real villain. With Bowler Hat Guy being in charge, he was such a moron that nobody believed that he was ever a threat. So they said we need a villainous threat. Their suggestion was to make him an actual serious villain, and we really didn't want to do that.

As the character developed, and we started developing that relationship between Bowler Hat Guy and the hat, we started thinking, "Oh, what if [the hat] is actually the mastermind behind the whole thing?" It was neat, because then we were able to redeem the villain. He was misguided, and he was hurt once upon a time, and then manipulated by this hat. He himself is not a bad person, he just got sent down the wrong path. So he was able to come back from that. And I like that because it didn't really happen a lot with Disney villains at the time.

I think Bowler Hat Guy got a little more manic, a little more of that man-child quality as we leaned into the fact that this character is actually a 10-year-old kid whose growth has been stunted. While his body has grown up, his heart and soul really haven't. It's frozen in time to when he was a little kid and he felt like he was wronged by Lewis.

Belzer: I'm not going to sit here and say, "It was better first time." Art is subjective. It changes. It's fluid. And where you have a director's vision and somebody comes in more than halfway through with different ideas, well, it's understandable. It's not their project, they're going to see it differently. The choice is to accept it or not. And again, largely because John did have a track record and he was the one in charge, Steve and the crew had to bend to that new beat of the drum. And I think we did pretty well.

Anderson: We did so many iterations of the movie. Many things stayed the same almost through every version. And then a lot of other things were wildly different from screening to screening. The first act of the movie, I felt like we had better versions of that. Not to say that I don't like what we ended up with, but I remember in general feeling like there was a different opening of the movie that I thought was better, that was changed from the Pixar notes.

It's like having a big table full of puzzle pieces, and in my head it's like, "There was a piece from that screening that I really liked and there was a piece from that one that I really liked. Let's put that with what we have here and we could make the ultimate version of the movie, or at least my ultimate version of the movie." I don't know if there was a wholesale complete 100% version that is the ultimate version for me. It was more like we could cherry-pick from some of these other versions and bring those in.

The Robinsons find their voices

Over the course of its many years in production, "Robinsons" also put its crew to work in the recording booth. And as the film entered its final stages, the cast was finalized.

Jen Rudin (casting director): So many of the in-house Disney Animation folks ended up staying in the movie. I think at one point, I recorded an art teacher or something because that's what happens when you're experimenting. Instead of having to hire an actor every time you want to hear something, you just grab people from the building and you're like, "Hey, can you go downstairs and record a couple of lines?"

Anderson: We call [them] scratch voices. So we did all of our own scratch, and it was very nice. Everybody really liked what I'd done as Bowler Hat Guy, but we did start talking with casting about potential candidates for the character — professional actors. But then soon after that, the studio said, "You know what, we decided we think you should stay doing the voice, because it has meshed with the character [in] everybody's minds." I was shocked. And then as it turns out, pretty much everybody on the story team does have a voice or two in the movie.

Rudin: Sometimes you get comfortable with a voice that you're like, "I can't even picture anybody else doing it." And then sometimes you're like, "That was great. Thank you so much for volunteering and helping us get the storyboards up. And now it's time to bring in Laurie Metcalf, a professional actor to voice the role."

Anderson: We got people like Laurie Metcalf, Angela Bassett, Harland Williams, Tom Kenny, and Ethan Sandler. This great cast of performers who really understood more of a theatrical animation voice type of acting. People with stage experience or stand-up comedy backgrounds who know how to appeal to an audience, which I personally think is better for animation than a lot of superstar actors. While many of them are great at what they do, I find that for animation, it's better to get people that have more of a stage background.

Harland Williams (voice of Carl): I think there was quite a few people up for the role of Carl. I like to improvise a lot during my auditions and just kind of let it fly. I think they really responded to that.

Anderson: Harland fit that bill perfectly. I had directed on a really silly cartoon show many years prior to "Meet the Robinsons" at a different studio, and he had done some voices for that show. His ability to improvise and come up with just off-the-wall, crazy things out of left field was so impressive that I thought, "Okay. I really like the notion of having that kind of mind in this movie."

And he was great. I mean, we would do it as written and then I would point to a particular line and say, "Can you just play around with that? Is there something else besides what we wrote on the page?" And he would just make stuff up. Some of it unusable. Funny, nonetheless. I have all the recordings and I used to listen to him in the car on the way home, on my commute, and just crack up and be so entertained by his ad-libs that we couldn't use.

I find improvisation to be really great in animation because there's just so much more that you can discover with the characters. It lets the actor own the character and inhabit the character when they're improvising in that character's skin.

Williams: It's helpful in everything really, just to be able to kind of fly by the seat of your pants. If your instincts are good, it can help. And if you're just being an attention hog, it can hurt. When you improv, you try and do it strategically, so that it's not overwhelming, but it's hopefully adding something that's usable. [In] most of my movies, I've been able to drop some good golden nuggets in. It's nice to have the freedom to do it.

Anderson: The philosophy we all had with casting the movie just in general was, "Can we find people that are really great performers?" And we tended to focus more on people that can do improv. People that have worked on the stage, in theater or stand-up comedy, that kind of thing. People that really understand how to play big and how to create broad characters.

For a while, because we had so many smaller roles in the movie, we thought, "What if we got one male and one female actor to come in and do all of the parts? All of the male Robinsons and all of the female Robinsons?" We started talking with a couple of female actors to do that and it didn't work out, which was totally fine. But, there are folks like Ethan Sandler in the film, who was a product of that. He does five or six characters in the movie, because he's extremely versatile and great with improvisation.

For the main roles of Lewis and Wilbur, we have to rewind back to the early storyboard screenings.

Anderson: The producer at the time very wisely said, "Since the main characters in this movie are two kids, we probably shouldn't have 30-year-old men do the voices. So what if we do actually hire some kids to come in to do scratch?"

Rudin: I understand it's much easier to hire a legal 18-year-old to voice a child. But to me, there's just nothing as authentic as a real 11-year-old boy playing an 11-year-old boy versus a grown woman playing that role.

Anderson: We didn't cast them. They weren't hired to do the roles. They were just hired to do the early versions. I think that's one of the hugest successes of that first screening, because [the kids] have to carry the movie, and boy did they ever. They really brought those characters to life, [so] we ended up offering the role to those two kids. So the two leads were set.

Assembling the ensemble

After recording scratch audio for the storyboard screenings, Wesley Singerman was cast as Wilbur and Daniel Hansen as Lewis. But "Meet The Robinsons" still had many years of production ahead — including the period after the Pixar merger, requiring rewrites and re-recordings.

Rudin: I cast "The Incredibles" with Spencer Fox, who voices Dash, and that timing worked out great because we were able to record the entire movie and he did all of the toys and ancillary products and his voice didn't change. But "Meet the Robinsons" was a couple of years. So you would start with an 11-year-old boy and the next thing you know, they're 14 and you know that their voice is about to change. It's so amazing to cast authentic child actors, and yet you're always faced with adolescence.

There ended up being two boys who voiced Lewis. Daniel Hansen was the original and then Jordan Fry came in and did some additional voices.

Jordan Fry (voice of Lewis): This was all just told to me when I was an 11-year-old kid: Stephen apparently was watching "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory" and heard my voice when I was playing Mike Teavee and was like, "Oh wow, that kid sounds very similar." So they had me come in and read for it.

When I was auditioning for "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory," I went through five rounds of auditions before I found out that I got it. The first thing that my mom said was, "Yeah, you're going to go in and it'll be like an audition." So I went in and I recorded at Disney, and it was really fun, really cool, and, no, I didn't really hear anything, but they kept having me come in and do recording sessions. I think it was probably around the fifth or sixth recording session that I was like, "So when am I going to find out whether I got this part or not?" And my mom was like, "Oh yeah, you've already had it for the last five sessions that we've done."

While plenty of crew members got the chance to contribute voices to the final film (including Anderson and writers Don Hall, Nathan Greno, and Joe Mateo), other characters were filled by well-known professionals Laurie Metcalf, Angela Bassett, and Adam West.

Rudin: This is so long ago that everything was still pretty much cassette tapes. So we would have a movie on a DVD and we'd be playing it in our office and then we would press record and take some sample dialogue from the movie, put it on a cassette tape, label it "Angela Bassett," and bring it upstairs to the development floor. The casting process was looking at the artwork of the character, closing your eyes, listening to the voice, and then thinking, "Is this the right voice to come out of the skull of the character?" We probably took Angela Bassett's voice from some random movie or TV show, cut it to a picture of Mildred, and then said, "Okay. Yeah, sounds great. Let's do it."

Angela Bassett was a big get for us and really exciting to have in the building. I always like to say she can read the phone book and it's fascinating. Every time she came for a recording session, I always popped down to listen.

Anderson: Rewinding a couple of years earlier, when I was working on "Emperor's New Groove," one of the iterations of the movie that didn't obviously didn't make it was that Kuzco spent a lot of time in the second act of that movie in Pachas village. And he met weird characters and one of them was this crazy conspiracy theorist whose name was Mochi. It was storyboarded, it was written, and they actually cast Adam West as this character and recorded him. He was hilarious as this character. And so — not that I didn't know he would be great anyways — but, having watched that recording session, I thought, "Okay, he's going to be that same kind of performer that we really need."

As for the Tom Selleck joke, it took on new life in the casting room.

Anderson: That was one of the moments that never changed in the entire evolution. It was by one of our story artists, Nathan Greno. He was storyboarding the idea of Wilbur [introducing] everybody in the family. So we gave him that assignment, he went away, he came back, and he had this weird out–of-left-field joke of, "What does your dad look like?" "Tom Selleck." [It was] a way to throw Lewis off the scent of who he really is.

And then as things went on, the idea was, "Well, what if we could actually get Tom Selleck to do the voice of Cornelius?" Which I never thought would happen, but lo and behold, there we are sitting in the story room with Tom Selleck and his team, pitching the movie to him.

We always wanted to make sure that the image onscreen was very realistic. Not caricatured and not Tom Selleck in the style of the movie, but either a photo or a realistic painting of Tom Selleck. Because then it's very clear that Wilbur is lying. That's really all that mattered — you need to laugh at the fact that Wilbur pulled something out of thin air that's totally not appropriate, but Lewis goes with it. Because why would he doubt him? And then if you know who Tom Selleck is, there's that extra layer.

Settling the soundtrack

Anderson: It's so lucky with all of the music folks that we were able to get unique and original music in the film. There were so many animated movies doing needle-drop-type things like "Shrek" and the Smash Mouth song. Even [at] Disney, "Chicken Little" had R.E.M in it.

There were several discussions around our movie. We had to demo a few versions of certain sequences with pop songs in them. One in particular that I remember was when Lewis and Wilbur go to the future, there was the Green Day song, "Welcome to Paradise," which was a hundred percent [because] it has the phrase "welcome to paradise." But the rest of it's not a really positive song so I was like, "No, no, no." Those were the kind of hoops we had to jump through with leadership before John came in. Luckily those didn't stick. Nothing against the Green Day song, because it's a great song, but I don't think that's the right marriage of music and moment.

The "Meet The Robinsons" soundtrack ended up including four original songs written for the film, performed by Rufus Wainwright, Jamie Cullum, and Rob Thomas.

Anderson: We had a temp song, "I Can See Clearly Now," that was in everybody's head for years as the end song. And then came our music executive, Chris Montan. I forget how Rob Thomas came up but we went, we met with him, and he was really great. We talked about him doing the end song and then he said, "I'm playing around with something. Let me finish it up and send it to you guys and see if you think it would work." And of course, when we heard it ... the fact that it starts with "Let it go," which is, essentially the theme of the movie: Keep moving forward! He hadn't even seen the movie at that point. So, as far as I remember, none of that was intentionally put together, but it's one of those things that just was right.

As soon as I heard it, I thought, "Yeah, that's the song." It's a lovely, sweet, emotional song. His demo was just him on a piano, so it was even more melancholy versus the produced version that ended up in the movie. But beautiful nonetheless. So we replaced, "I Can See Clearly Now" with Rob's demo for the next screening, and people didn't know how to process it because "I Can See Clearly Now" is this very upbeat, peppy kind of positive. Rob Thomas' song was positive, but the sound of it was so much more deep, so people thought it was a beautiful song, but they were like, "Oh, but I don't know, does that work?" But I was like, "Yeah, trust us. It'll work." And of course, once it was all produced and put together, it was perfect.

Another meaningful collaboration

Despite all of the original songs penned for the film, pop music still found its way into the "Meet The Robinsons" legacy. The soundtrack (which also features The All-American Rejects and They Might Be Giants) includes the Jonas Brothers' rendition of "Kids of the Future."

Anderson: I think Disney Channel saw an opportunity to do a cross-promotional thing with our movie and the Jonas Brothers. They did a music video of it that aired on Disney Channel and it did have scenes from the movie cut into it. And the Jonas Brothers were at our first press junket, so they did help promote the movie. They even played at the premiere and I have a photo. My son was probably six or seven at the time, so big Jonas Brothers fan. I have a picture of him with the Jonas Brothers, which I'm told he used at school for some playground cred for quite a while.

But they were also lovely. I mean, my gosh, they were so nice. I remember the press day that we had, the first press junket, was at the studio in Burbank. And I remember just sitting in a big green room and chatting with them and they were just so nice and so down to earth and complimentary about the movie.

I don't even know who wrote the new lyrics for the song. I remember being in a meeting with the idea being rolled out to us. They'd already shot the video [and] recorded the song. It had already been written. I remember sitting at a table with the lyrics printed out on a piece of paper as we were following along. And to be honest, kind of going, "What is this and where? How did this happen? What's going on?" Because this doesn't have anything to do with the movie. But again, it became clear that, "Okay, this is a great tool to promote the movie."

As for the soundtrack, decorated composer Danny Elfman stepped in.

Anderson: It was an absolute dream come true for me to be able to work with Danny. There's only been a couple times so far in my career that I've been really starstruck and he was probably the first one. I learned quite a lot from Danny about process, which is something that had gotten teed up earlier in the development of "Meet the Robinsons," but working with Danny really hit home.

We first sat down to what we call a spotting session, where we watched through the movie and talk about what music do we want and where we want the music. He came to the studio and we sat down in the editorial room and started going through the movie and I would stop and say, "Okay here, what if the piece of music is X, Y, and Z." And I would try to describe the piece of music. How it should sound, how it should feel.

He was like, "Okay, okay," but didn't seem incredibly comfortable with how I was talking about things. After doing that a few times, he finally said, "Okay, you know what? Let's stop here for a second." He said, "Rather than talk about something that doesn't exist yet, why don't we just decide where we want music and I'll go away and write a bunch of stuff, and then we can talk about it after I write it. But then we'll be talking about something that actually exists that we can set in front of us on the table."

That was really eye-opening [and] maybe obvious to a lot of other people, but there was just something about that moment, that I realized, "That's exactly right." There [have been] so many times since then where I sit in meetings and we're talking about something that doesn't exist yet. If you want to make a drawing, it's so easy to sit and stare at the blank piece of paper and think about all the things you could draw as opposed to, well, just draw something. And then if you don't like that, you can draw something else, but at least now you've started.

It was a great lesson about how to approach working with a composer and the bigger picture for me was this really amazing way of looking at the creative process.

Finding the right words

Dykstra: I think every movie means different things to different people. ["Meet The Robinsons"] had an edge to it that caught my attention personally, and that is the whole mantra of "Keep moving forward." And of course, that quote came from Disney himself. I think that's such an important part of life. That quote at the end of the movie just really hit home for me. It's so easy to live in the past and not think about the present or the future, and it's very important to think about where you are right now. I think that Steve really brought that home.

Anderson: Having "Keep moving forward" in the movie came very early on in our story development. It came from myself and the original writer, his name is John Bernstein. He was talking about a friend of his who was adopted, and who had actually found his birth parents. And then I was talking about my own experience, knowing very early that I was adopted and as a kid being very passionate about one day finding out who my birth parents are. And then one day realizing, "You know what? I've exceeded the age where I could find out who they are."

My parents always said, "When you're 18, you're going to be old enough to go get your birth records and find who they are." And then cut to, years later, I'm 25. I realized, "Oh, I could have been doing that. I could have been searching for them all these years, but actually forgot about it because I was more focused on the family that I do have; on the family that I'm now creating with my wife and son, and the future that I'm building in animation at Disney." That became more important to me than looking backward. And so all of those things combined to create that notion of finding hope in life by looking to the future and not dwelling on the past. And then we were able to then distill that down into that motto, "Keep moving forward."

That was what Wilbur was driving into Lewis' head through the whole movie. And that was Wilbur's father's motto. And then even several years later, I was reading a book of quotes by Walt Disney. And I found that "keep moving forward" quote, and people said, "Oh, you should put that at the end of the movie, because that's amazing that Walt Disney actually said those three words."

So much of the DNA of "Meet the Robinsons" is rooted in that futurism, that optimistic look at how the world can be a better place — like Walt Disney had through Tomorrowland in the theme parks, and Epcot in Florida. I was always inspired by those things as a kid, and I really wanted to bring that feeling to the future of Robinson's. So then once we put that on the end, it brought every thing together and made it all come full circle.

Keep moving forward

"Meet the Robinsons" finally arrived in theaters in March 2007, a year later than it was originally slated for release and nearly two decades after William Joyce and Bill Borden first pursued the adaptation.

Joyce: ["Meet The Robinsons"] was my first movie deal and it took the longest to get made. I didn't contractually have the controls that I would [today], but I learned a lot about how to make sure that I do. On the whole, for all the years that tumbled by, and all the changes that were made, and all the possibilities that came and went, it stayed true to the spirit of the idea. Which is better than most people can say in the propitious land of filmmaking. There was something about that 32-page picture book through all those years. There's something hopeful and optimistic and lyrical and lovely about the idea that it just wouldn't die.

Anderson: I'm very proud of the movie that was released. There's always things that you look back on and say, "Oh, maybe that would've been better or what if we'd done that," or "What if we had more time to do this?" But that's the filmmaking process. I think it's any creative process. A creator will always be able to look back on previous iterations and wonder, "Would that have been better?"

Joyce: Animation, as far as my experience, tends to always go through one gigantic panic where everybody's tearing their hair out and jumping out the window for a little while, but then the ship manages to make it into harbor.

Belzer: Often with change, there is challenge, but there's also reward at the end. And the reward I look at is the film. I'm still very, very happy and proud to have been part of that film, all the way from the designs of Bill Joyce to how Steve put it together. It's a fun process, animated films. And when you work on a project like that where everybody's pulling together for a common cause, a common good, and it comes out as well as it did, it feels pretty great and happy to be a part of something like that.

Joyce: When I go to events, when I go speak at schools or speak at book signings or speak at conventions, there will be people in line that will recite snippets of dialogue from "Meet the Robinsons," and explain, "Oh my god, I loved that movie so much when I was a kid." Now they're 20 and they're bringing their kids to get my books. And it's extremely satisfying to sit there and hear that. To hear that it mattered to somebody when they were 5, 6, 7, and it still matters to them and that they're sharing it with their kids, that is every storyteller's dream come true.

So however hard it was to make the thing, whatever anguish went into it, whatever money was thrown out the window or ended up on the screen ... all the blood and all the carnage, the audience has no clue. A seven-year-old saw [the movie] when it came out, or sees it now for the first time and they don't know any of that stuff. They enjoy it for what they see. They don't know what we didn't get to do or what we fought over. And if it pleases them, then everything's fine. It's a victory.