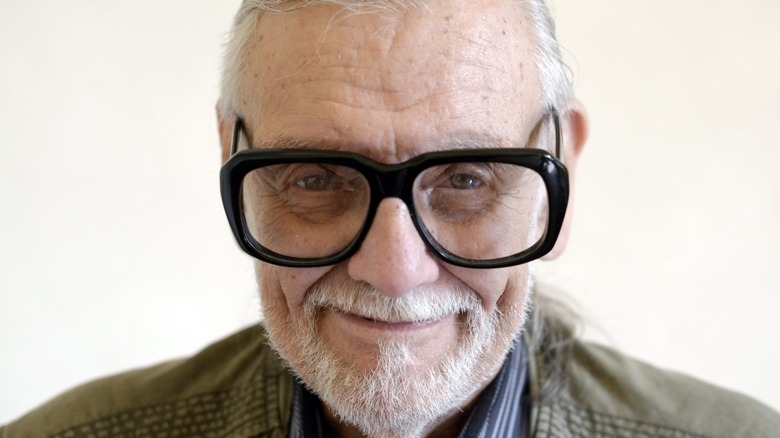

All 17 George Romero Films, Ranked Worst To Best

Even if George A. Romero had only made his zombie films, he would still have a well-earned spot in the cinematic canon. As famous as he is for his "...of the Dead" franchise, though, he's not recognized widely enough as a multi-talented auteur with an incisive lens on American politics and culture. Romero was a brilliant writer with an ear for naturalistic yet meaningful dialogue and an editor whose unique style — rapid-fire but loose, as narrative-driven as it is mood-driven — turned his films into arthouse fare for the masses.

Though most directors with any longevity have a few "lower-tier" works in their catalog, it can be difficult to rank Romero's films given how many bonafide classics he directed. This list will do just that. From missteps both early and late in his career to at least three masterpieces — each of which could easily take the number one spot — here are George A. Romero's films ranked from worst to best.

17. There's Always Vanilla (1971)

"There's Always Vanilla" is a bit of an oddity in Romero's filmography. It's the only romantic comedy in his oeuvre. Well, it's billed as a romantic comedy, but it plays more like a satirical drama. It even has occasional horror elements. One chase scene, in particular, would fit perfectly in Romero's zombie films. Horror and suspense were home to Romero, and his style shines through regardless of the film's purported genre. "There's Always Vanilla" is a film about disillusionment and eschewing conventionality. This fascination with counterculture is a throughline for Romero's work, but the movie is simply too aimless to rank among his best.

Despite script issues (this is one of the few films that Romero didn't write himself), Romero's political interests are on full display. Mentions of the Vietnam War float throughout the film. When Chris (Raymond Laine) is offered a job for an Army recruiting campaign, he refuses, even though he's in desperate need of money. His girlfriend, Lynn (Judith Ridley), attempts to get an abortion. The medical procedure was illegal at the time, and the horrific nature of her situation is where Romero's horror chops shine. These heavy subjects, combined with Romero's keen interest in exposing hypocrisy and injustice, don't make for a light-hearted romantic comedy. The result is fascinating in its mismatched oddness, though the movie can be a bit of a chore to get through.

16. Survival of the Dead (2009)

The National Guard is falling apart in the face of the zombie pandemic, and a small group of renegade soldiers robs its way across the countryside in search of a safe haven, ideally an island. When they learn of Plum Island from another survivor, they head there and find two warring Irish families: the O'Flynns and the Muldoons. The O'Flynns want to kill all the zombies they find, while the Muldoons want to keep their undead loved ones alive until a cure can be found. The "us vs. them" mentality that courses throughout Romero's work mutates again, and "Survival of the Dead" ends in a gorgeous final shot that underscores the futility of factionalism.

Romero's last film serves as a disappointing coda to his "Dead" franchise. It still finds new avenues to explore in his ongoing zombie saga, including the intriguing philosophical battle between the two families and the prescient inclusion of late-night talk show hosts making zombie jokes. Overall, though, it doesn't add enough to Romero's zombie mythos. It often feels like a retread of better movies rather than a fresh entry in the franchise. Add in CGI effects that have aged poorly instead of the stellar physical effects his other films are known for, and "Survival of the Dead" sees Romero's directing career end with a whimper.

15. Diary of the Dead (2007)

Much like "Survival of the Dead," Romero's foray into found footage, "Diary of the Dead," often feels like a retread of his earlier films rather than a fresh take on zombies. However, Romero mines the found footage concept for some interesting cultural commentary, which earns it a higher spot on this list than his final film. At the beginning of the zombie outbreak, a group of students shooting a horror movie and a news crew reporting on reanimated corpses find themselves fighting zombies and recording the entire saga.

Fascinating ethical questions arise. Romero was never the most subtle filmmaker (though that doesn't dull his sharpness in the slightest), and he writes a few lines here that give viewers plenty to chew on. "Is it your job as a journalist just to keep shooting?" becomes more and more relevant every day, as bystanders record horrific events on their phones rather than stepping in to help people. Where is the line between reporting on an event to inform people and spur them to action and simply gawking at the terrors of daily life?

Debra (Michelle Morgan) narrates the film, and when she witnesses the common Romero trope of small-town locals making a game out of killing zombies, she asks, "Are we worth saving? You tell me." Romero often blurs the lines between humans and zombies, but rarely is he more pointed in the comparison than in this question posed directly to the audience. "Diary of the Dead" doesn't rank among his best films, but it still has something to say.

14. Two Evil Eyes (1990)

George Romero reunites with "Dawn of the Dead" co-producer Dario Argento on "Two Evil Eyes." Each director gets half of the movie to tell a story based on the works of Edgar Allan Poe, with Romero's "The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar" constituting the first half of the film. Romero's segment is the better of the pair. If Argento's "The Black Cat" had been stronger, "Two Evil Eyes" likely would have ranked higher on this list.

Based on the Poe short story of the same name, "The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar" follows Jessica Valdemar (Adrienne Barbeau) as she and her lover, Dr. Robert Hoffman (Ramy Zada), try to swindle her elderly, dying husband, Ernest (Bingo O'Malley), out of his fortune. When Ernest dies too early for them to collect, they hide his body in a freezer. Ernest isn't quiet in death, though, and his haunting of Jessica and Robert drives them mad.

Though there's less tongue-in-cheek humor, there's still a delightful "Creepshow" vibe to Romero's entry in "Two Evil Eyes." Part of that is owed to the cast (Barbeau, O'Malley, Tom Atkins, and E.G. Marshall appear in the film), and part is owed to the spookiness of Romero's approach to anthology horror. When he adapts other horror writers' material, he approaches it with an irrepressible love for the genre. He's clearly having fun, and that love for horror comes through on the screen.

13. Bruiser (2000)

"Bruiser" is a very Y2K film, but that's not meant as an insult. Like many films, its wardrobe and production design immediately identify it as a product of its specific time. However, there's a universality to Romero's depiction of corporate culture at the turn of the 21st century that, like so much of his work, only gets more and more relevant as time goes on. Henry (Jason Flemyng) is the creative director of a magazine called "Bruiser." His boss, Milo (Peter Stormare), is the walking embodiment of toxic masculinity — and he happens to be having an affair with Henry's wife, Janine (Nina Garbiras). Consequently, Henry feels invisible at home and work. One morning, he awakens to find his face transformed into a blank, white mask and begins a killing spree as an outlet for his repressed rage.

"Bruiser" is fascinating when viewed in connection with Romero's "Dead" films. Both deal with dehumanization, but in "Bruiser," no radiation is needed to begin the apocalypse. The toxicity of American corporate culture and warped ideas of masculinity are all you need to turn people into the living dead. Stripped of individuality, mindlessly following rather than using their own free will, shambling through life with no aim other than to consume and kill or be killed — it's hard to tell the difference between a zombie and a typical office worker. "Bruiser" might not reach the heights of Romero's greatest films, but it's still a disturbing, prescient look at American life.

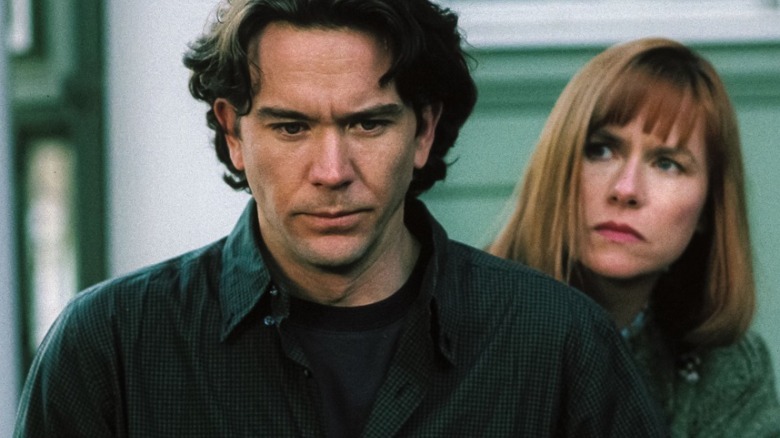

12. The Dark Half (1993)

Though George Romero had worked with Stephen King before, "The Dark Half" was his first time adapting one of King's novels into a feature film. The results are mostly good, though the movie falters near the end and could stand to be shorter. Romero was an expansive filmmaker who often let his stories unfold at a deliberate pace. Usually, that approach worked for him, but it doesn't coalesce as neatly when adapting King's novel. Still, "The Dark Half" is a fascinating story with an impressive dual performance from Timothy Hutton at its center.

Hutton plays Thad Beaumont, a writer of literary fiction (i.e., "respectable" books), who writes less critically lauded novels under the pen name George Stark. Stark's books are bestsellers, though, and Beaumont is torn between his artistic aspirations and his financial ambitions. He's also torn between his "civilized" self and the more brutal aspects of his personality that Stark represents. It's an intriguing meditation on the relationship between art and the self. King loves writing about writers, and it's compelling to see two horror masters reflect on the duality inherent in exploring the darker parts of humanity.

Although the film meanders a bit in the middle, Hutton's performances alone are worth the price of admission. Romero adds some imagery that foreshadows the mask in "Bruiser" (along with what seems to be a reference to the trailer for "Suspiria," directed by his friend Dario Argento) and a scene that calls to mind the recent horror hit "Malignant." It's especially chilling viewing for writers, as they're hit with the profound and disheartening simplicity of the line, "The only way to do it is to do it."

11. The Amusement Park (1975)

Only George A. Romero could turn an educational film commissioned by the Lutheran Service Society of Western Pennsylvania into the bleakest and most frightening film of his career. "The Amusement Park" was intended to be a film about elder abuse, but rather than focusing on individuals responsible for such horrors, Romero and writer Wally Cook indict the entire country for their systematic abuse and neglect of the elderly. "The Amusement Park" is an absolute nightmare of intentionally jarring edits, uncomfortable warped close-ups, discordant tones, and ticking clocks that underscore the inevitability of its horrifying scenes happening to the viewer in the future.

The film uses an amusement park as a metaphor to show the discrimination and lack of compassion that elderly people deal with as well as the hurdles they face. There is no safety net or infrastructure in place to make sure elderly people can live with dignity. The film places the viewer squarely in the shoes of star Lincoln Maazel, who begins the film cheery and eager for the amusement park but ends up battered, bruised, and hopeless. He tells the viewer in a wraparound segment: "Remember as you watch the film, one day, you will be old." Rarely has such a chilling reminder of mortality been put on film, and rarely has there been such a stirring call to change the system that fails the elderly every single day in America.

10. Season of the Witch (1973)

"Season of the Witch" is George Romero's most openly feminist film. It tells the story of Joan Mitchell (Jan White), a neglected suburban housewife who lives with her husband, Jack (Bill Thunhurst), and her 19-year-old daughter, Nikki (Joedda McClain). Jack alternates between ignoring Joan and abusing her, verbally and physically. Joan longs for some sort of escape, and she finds it, first in an affair with Gregg (Raymond Laine), a student teacher at Nikki's college, and then, in the practice of witchcraft. Newly empowered, both literally and figuratively, Joan finds a way to free herself from Jack and become the person she was meant to be.

"Season of the Witch" opens with a dream sequence that encapsulates exactly how Jack makes Joan feel. He leads her on a leash and then places her in a kennel. Once again, Romero explores the alienation, isolation, and dehumanization of modern life, but this time, he focuses specifically on how and why these issues affect women, who are often trapped by domesticity. Romero's artful, quirky editing is on full display again. The first witchcraft scene, in particular, is edited to keep the viewer off balance with a unique tempo that only Romero could conceive. The sound effects sound like electronic screams that perfectly match the frustrated screams that Joan keeps stifled inside as she tries to make it through each day. There's a fascinating generational divide at play between Joan and Nikki, and it's a joy to see Joan revel in shedding the propriety expected of her as a middle-aged woman. Combine the sharply feminist tone and a well-timed Donovan needle drop, and you've got a Romero film that belongs in the top ten.

9. Monkey Shines (1988)

George Romero takes aim at issues surrounding the rights of the disabled, animal rights, and medical malpractice in "Monkey Shines." The film is slightly different from most of his other work. Again, part of the difference seems to be in adapting others' material vs. writing his own original screenplays, as the film was based on Michael Stewart's book of the same name. It's also a major studio film, which rarely meshes well with the indie outsider sensibilities of an auteur like Romero.

Allan Mann (Jason Beghe) is an athlete who gets hit by a truck and becomes a quadriplegic. His friend, Geoffrey (John Pankow), recommends a service animal in the form of a Capuchin monkey, whom Allan names Ella. Unbeknownst to Allan, Geoffrey has been experimenting on Ella to increase her intelligence. The serum he injects her with seems to have caused a psychic link between Allan and Ella, both of whom grow increasingly angry and irritable. As Allan's bitterness over his condition grows, especially after he finds out he may have been misdiagnosed by an unethical doctor, Ella begins lashing out in increasingly troubling ways at the people Allan believes have wronged him.

Regardless of studio interference, George A. Romero knew how to maintain tension, and "Monkey Shines" is a sharp thriller that takes more than a few cues from Hitchcock but still remains very much Romero's movie. Most of the action takes place in Allan's home, but Romero steadily builds suspense despite the limited location. It may be slicker than most of his other films, but "Monkey Shines" is still an effective horror movie.

8. Land of the Dead (2005)

"Land of the Dead" is only the fourth best in Romero's zombie franchise, but considering the films it's up against, that's not a bad place to be. Years after the zombie outbreak began, feudal governments have popped up in major cities in the United States. In Philadelphia, the privileged few live in a high-rise called Fiddler's Green (a clear reference to Nero fiddling while Rome burned), while the rest of the survivors subsist on the streets. A group of fighters comes into conflict with the leader of Fiddler's Green, Paul Kaufman (Dennis Hopper), and, inevitably, his palatial fortress comes crumbling down around him.

There are two fascinating things about "Land of the Dead." First is how it advances Romero's idea of the zombies evolving. A zombie called Big Daddy (Eugene Clark) watches and learns, teaching other zombies to use weapons and walk underwater to reach Fiddler's Green and tear it down. Second is Romero's evolution of the idea that the zombies aren't the true villains in his films. That has always been the case, but it has never been more clear that zombies and underprivileged humans are in a class war against the rich. "Eat the rich" becomes literal in "Land of the Dead," as Big Daddy nods in salute to the underprivileged survivors after attacking Fiddler's Green. Romero has always been keenly interested in how class issues affect human survival, but "Land of the Dead" is his most explicit exploration of class solidarity.

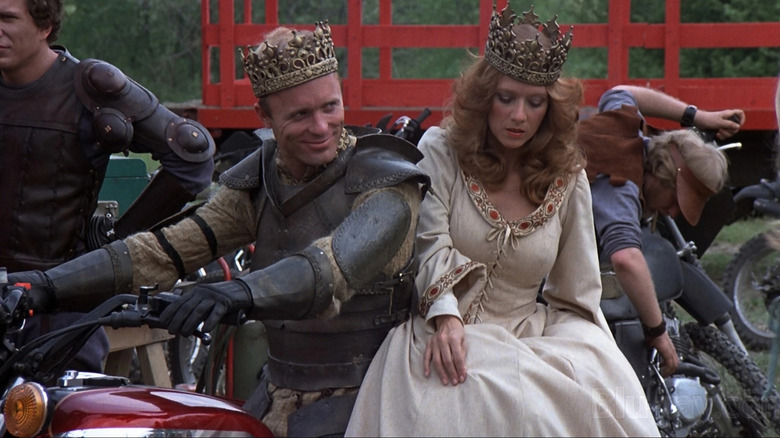

7. Knightriders (1981)

If the premise of "Knightriders" sounds like a joke, that's because it is. Motorcycle-riding Renaissance fair performers travel the country, living and breathing the courtly life they play-act for paying crowds. King William (aka. Billy, played by Ed Harris) begins to see splintering factions in his group, with the largest one led by Sir Morgan (special effects master and frequent George Romero collaborator Tom Savini). Though there are suspenseful sequences, there's no horror in "Knightriders." Still, Romero's political fascinations are clear and present, and the narrative's interpersonal dynamics are fascinating and heartbreaking.

Much of Romero's work is preoccupied with biker subcultures, and "Knightriders" certainly features a unique one: jousting bikers. His movies also have a decidedly anti-authoritarian slant, and this film is filled with critiques of corrupt cops in the small towns Billy and his troupe travel through. One of the last things Billy does in the film is beating up a crooked cop, and it's a refreshingly cathartic moment. Romero was fond of ambiguity and realistically downbeat endings, so Billy doling out some well-deserved justice in the final reel is a welcome change of pace. "Knightriders" might have an offbeat premise, especially for a director known for his horror films, but this is, first and foremost, a Romero movie, and fans are missing out if they dismiss it.

6. The Crazies (1973)

George Romero was rarely subtle, but he was always artful. "The Crazies" is a scathing critique of the U.S. military's actions during the Vietnam War, but in true Romero form, it's eerily prescient now. It's easy to draw parallels between the government's botched response to a viral contagion in the film and the COVID pandemic.

Also known as "Code Name Trixie," the film centers on a small Pennsylvania town as an experimental military bioweapon is accidentally unleashed on the residents when a cargo plane crashes near its water supply. The virus either kills you or drives you mad. There are no other options. When the military intervenes to try to stop the spread of the virus, they round up townspeople, terrifying them or outright killing them. Romero reveals that many men in the chain of command are just following orders from higher-ups that come up with evil schemes and then try to cover their tracks once word gets out. "The Crazies" is one of Romero's most cynical films, but it's also one of his most enduring.

There's some brilliant imagery in the film. The framing keeps the viewer off balance and reflects that the residents' world is now off-kilter. At one point, a soldier, his identity hidden by a gas mask and a white biohazard suit, knocks over some toy soldiers that a young boy had been playing with just before being dragged out of his house, kicking and screaming. Those few seconds perfectly encapsulate the film's message: "The Army ain't nobody's friend, man."

5. Creepshow (1982)

"Creepshow" is George Romero's most successful collaboration with Stephen King, who wrote this horror anthology film. Inspired by the EC horror comics of the 1950s, with their gleefully gruesome tales and bitterly ironic endings, "Creepshow" has a wicked sense of humor. Romero can be very funny, but the goofiness of this film is unrivaled by any other work in his filmography. In "The Lonesome Death of Jordy Verrill," a farmer (played by King himself) finds a meteor and daydreams of getting paid for it by the "Department of Meteors." In "The Crate," Professor Henry Northup (Hal Holbrook) daydreams about shooting his abusive wife, Billie (Adrienne Barbeau), as his friends and colleague look on and give him an approving golf clap. It's a very silly movie, but charmingly and hilariously so.

In keeping with both EC Comics and Romero's penchant for darkness, there is an acid tinge to the goofy anthology. The Creep, who shows up as a spectral Grim Reaper figure in the wraparound segments, appears before a young boy (King's son Joe Hill) uses a mail-order voodoo doll to get revenge on his abusive father (Tom Atkins), who doesn't want him reading comic books. Making sure no one escapes unscathed, the stories warn of the dangers of vengeance, greed, and cruelty. Always taking aim at human failings, Romero combines his fascination (and disappointment) with human nature with his love for the comic books of his youth, and the result is a horror classic.

4. Day of the Dead (1985)

"Day of the Dead" has the best opening in George Romero's entire filmography. A rotting corpse missing its lower jaw, its tongue lolling, stands silhouetted against a tropical blue sky as the title comes up. Newspapers with the headline "The Dead Walk!" blow around an abandoned town as the best gore and effects in the "Living Dead" franchise take center stage.

More than any other "Dead" film, "Day of the Dead" is a pressure cooker. The tension is almost unbearable as a group of scientists butt heads with a small military squad in an underground bunker devoted to finding a scientific way to defeat the zombies. The search is futile, though. As John (Terry Alexander), the helicopter pilot, says, "This is a great big 14-mile tombstone, with an epitaph on it that nobody gonna bother to read." This is the genius of Romero's dialogue. He can give his characters beautiful, bleak words that are profound and mundane all at the same time.

The line between zombies and humans continues to blur, as the zombies evolve and the humans devolve. The military men kill the scientists on a whim and threaten Dr. Sarah Bowman (Lori Cardille), the only woman on the base, with sexual violence. Once again, Romero's anti-authoritarian and anti-military stances show up as does his ability to take a limited location and turn it into a nightmare of tension and suspense. There's not much to criticize "Day of the Dead" for, and a film of this caliber in many other directors' filmographies would nab the top spot.

3. Martin (1977)

It's very tempting to put "Martin" at the No. 1 spot on this list. It's George Romero's most arthouse film, though its roots are squarely in working-class Pittsburgh. Martin (John Amplas) is a young man who goes to live with his elderly cousin, Tateh Cuda (Lincoln Maazel). Cuda believes that Martin has inherited the family curse and is a vampire who must be destroyed if he kills again. Martin mocks Cuda for his superstitions, but he is a serial killer who preys on women and drinks their blood. It's a fascinating look at the darkness within the human soul, the impact of superstition on the human psyche, and generational trauma. If Martin hadn't grown up being told of this family curse, would he have had such a fascination with human blood and connected it in his mind with his burgeoning sexuality?

Romero's talent for filming suspense was never better than in "Martin." In one standout sequence, Martin breaks into a woman's house to attack her after her husband has left town, but he unexpectedly finds her in bed with her lover. The cat-and-mouse-and-mouse game that arises is the most white-knuckle sequence Romero ever filmed. Its surprising cuts and claustrophobic framing turn the spacious house into a series of traps, both for Martin and his intended victim(s). "Martin" is a horror masterpiece that features some of the best scenes and raises the most interesting philosophical questions of Romero's career. The only reason it's not No. 1 on this list is that Romero made a few masterpieces — two of which are even better than this one.

2. Night of the Living Dead (1968)

Though George Romero often downplayed the cultural significance of his first film, it's hard to overstate what a watershed moment "Night of the Living Dead" was. Not only did he reinvent the zombie movie by connecting the undead to radiation from a NASA probe rather than Haitian Vodou, but he also made a Black man (Duane Jones) the hero of his film in 1968. With its famously downbeat ending that tapped into contemporary concerns about racism and police brutality, "Night of the Living Dead" was a game-changer, pure and simple.

Given its legendary status, it can be easy to forget how watchable it is. "Night of the Living Dead" is no historical document. It's a living, breathing film that gets richer as the years go by. Though this was Romero's feature debut, many hallmarks of his artistry are already evident. The framing of the people huddling for shelter in the farmhouse is thrilling and unsettling, with the low angles turning a small limited location, with no action other than listening to a radio, into an incredibly dynamic scene. Barbra's (Judith O'Dea) face seen through a twirling music box is a standout shot, and Duane Jones's monologue about a pack of zombies chasing a flaming truck is a master class in both acting and screenwriting.

Jones' performance is chilling. His thousand-yard stare tells you everything you need to know about the horrors these people are experiencing. It's also a brilliant way to deliver exposition on a budget. When you have an actor of Jones's caliber, he can give a speech that conveys more than actually showing a flaming truck being chased by zombies ever could. Visceral and unvarnished, "Night of the Living Dead" is a gut punch to viewers that's both a wake-up call and a landmark in independent filmmaking.

1. Dawn of the Dead (1978)

Filming a sequel to a groundbreaking film 10 years later and creating another masterpiece is quite the cinematic flex. That's George A. Romero. Like "Night of the Living Dead," "Dawn of the Dead" takes place at the beginning of the zombie outbreak. This time, it's in the city rather than the countryside. Overpopulation, particularly in low-income housing where residents of color are crammed in, makes the zombie problem that much worse, as does the media's insistence on staying relevant rather than being accurate. Police discipline (a phrase Romero would have scoffed at) breaks down as SWAT members begin to lose their minds or desert.

Two such deserters are Peter (Ken Foree) and Roger (Scott Reiniger), who join forces with helicopter pilot Stephen (David Emge) and his girlfriend, news producer Fran Parker (Gaylen Ross). They fly off in search of a safe haven, and they think they've found it in an abandoned shopping mall. In a clear jab at American consumerism and the emptiness of modern life, zombies have overrun the mall. The four survivors band together as best they can to defend the mall, but they soon encounter even more interference, this time from human invaders. Greed and toxic masculinity are the true villains of the film.

"Dawn of the Dead" is more epic in scale than its predecessor. Its runtime, physical locations, and philosophical interests are more expansive than in "Night of the Living Dead." Romero leveled up from his previous work, sustaining a sprawling narrative, tracking the evolution of the zombies, and introducing new sociopolitical concerns into his filmography. It may seem impossible to follow up a groundbreaking film such as "Night of the Living Dead" with an equally impressive one, but that's exactly what Romero did, and that is why "Dawn of the Dead" remains his finest film.