Steven Spielberg's The Fabelmans Hits Close To Home

Spoilers ahead for "The Fabelmans"

At the start of "The Fabelmans," young Sammy Fabelman goes to his first motion picture — "The Greatest Show on Earth" — and dreams of the epic train crash he saw on the screen. He wants so badly to recreate this celluloid nightmare that he films it over and over again with his model train set and his dad's 8mm camera. It's the first hint of a virus that will never let him go.

For the longest time, I thought I was alone — myself solely afflicted with this disease, but watching Steven Spielberg put his semi-autobiographical film on the big screen felt like a revelation. Maybe I'm "normal." Maybe I'm not so "crazy." Maybe I'm not so unique.

In the film, Sammy Fabelman takes his filmmaking one step further through each stage of his life, set against the backdrop of his lovely but at times tense and heartbreaking home life. He sees the truth through the lens of the camera, even when he's not intending to. Filming a camping trip with the family 8mm he even catches glimpses of his mother's shocking truth, cheating on his father.

Understanding me

Until "The Fabelmans," I've never watched a film before that understood that drive to piece film together — to cut it, to handle it, to live it, to breath it. Some have had their moments— "Cinema Paradiso" feels closest. But "The Fabelmans" understood me — Spielberg understood me — in a way I sometimes barely understand myself. Michelle Williams and Paul Dano bring Sammy's parents to life with rich depth and honesty. Sammy's mother understands at once the difficult choices Sammy will have to make for his art and encourages him. Sammy's father struggles to comprehend it and nurtures it as best as he can but is lost in his own, more science-minded head.

For Sammy's part, he's alone. Yes, he has siblings, but the film feels like he's apart from them unless they're the subject of his films.

He's singularly afflicted with the desire to make films that no one else can be that close to him.

The film is about much more than the sickness of film, but more broadly the sickness of art. We live in a society that does not promote art or value it in a way that makes it an easy life for those without privilege. How many Steven Spielbergs has the world missed out on because of the demands of supporting a family or the ills of a capitalist society? How does one live with that virus of artistic expression in a world that doesn't care, let alone thrive?

A family story

The film is as much Michelle Williams' story as Mitzi Fabelman as much as it is Gabriel LaBelle's as Sammy. She's an artist who has had to put aside her dreams of being an artist for the standard '50s dream of raising a family as a housewife. The story hits hard and she has to make impossible decisions.

But that's what every artist goes through, isn't it? Mitzi wants to be a concert pianist. Sammy wants to be a picture maker. They both want to make art and it drives them. I can attest: film is one of the most powerful of the artistic viral infections. As I watched, I saw visions of my own life, then and now, wrapped up in a powerful package that left me speechless.

As Sammy gets his first editing machine, I was taken to my time cutting short films shot on compact VHS, tape to tape at my school's single edit bay. As Sammy makes his World War II movies, I was transported to my days in high school, cruising the local second-hand and military surplus stores every week with a friend so we could make our own World War II and Vietnam movies, collecting props and costumes with every stray penny we had. As Sammy wheels out his camera on a stroller, I think of every borrowed wheelchair my friends and I used. And I think of all of the camera gear we built from scrap lumber to get that one cool shot to capture with our Hi8 cameras.

And as Sammy nears the climax of the film, I saw myself rejecting school as he does. Right out of high school, I couldn't afford to go to film school, so my friend, writing partner, and co-director since we were 13, built a spaceship in my mom's backyard and filmed a movie inside of it. Nothing would stop us from living our dreams as filmmakers. I worked at movie theaters, devouring every movie I could, drinking in their xenon-lit promises, cutting and splicing 35mm prints by night and doing my best to shoot short films in 16mm and feature films that failed to launch. I wrote screenplay after screenplay after screenplay. The bug never left.

I wrote and produced award-winning documentaries and made my life as a freelance filmmaker and writer.

It was working.

But in the midst of all of that, I got married. I filmed my wedding on 8mm. I had a couple of kids and things were great, but choices had to be made. My oldest son lit himself on fire at one point, just as the economy went belly-up. I took a steady paycheck in an adjacent but less creative field, never quite losing my dreams.

Just keep shooting

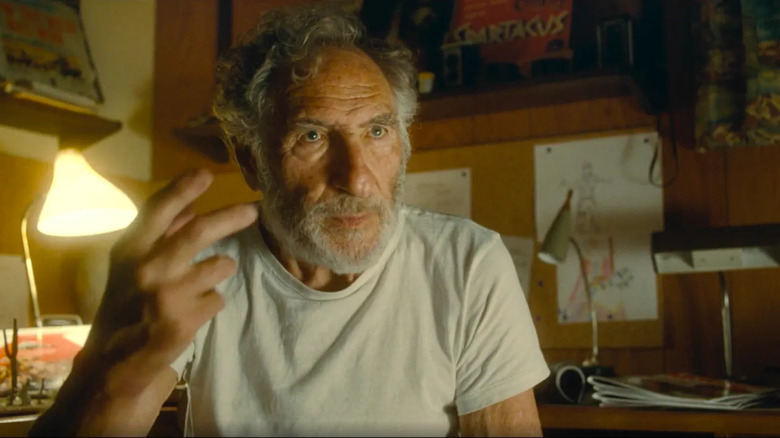

In the film, when Mitzi begins to falter in her life because she's turned into something she wasn't built to be, I saw myself in her every bit as much as I saw myself in Sammy. Uncle Boris — played by Judd Hirsch in a small but vital role — sees it, too. He tells Sammy he's going to have to pick between his family or his art and there won't actually be a choice. And Mitzi has to make that choice, too, between what makes her happy and what is expected of her. I've been there, having to sit there for an announcement of divorce and having to sit the kids down for it myself. It's hard and it's photographed here in such a moving, honest way that it shows us something about ourselves and each other. Though all of my circumstances leading to be a child of divorce and divorced myself are different, the scene in "The Fabelmans" is so unflinchingly honest.

Uncle Boris's prediction leaves Sammy in disbelief, but deep down he knows it's true. No matter what, Sammy has to follow his dream and that leads him all the way to John Ford's office. Ford (played to perfection by David Lynch) gives Sammy all of the bizarre advice he needs from exactly the right person he needs to hear it from. Just like Steven Spielberg in his early days. Spielberg has related this story many times in his life. There's a YouTube video of him relaying it to Jon Favreau, Brian Grazer, and Ron Howard and I must have watched it a hundred times in awe. And I realized I had a John Ford moment like that myself. If you read my work here at /Film, you know I'm a big "Star Wars" fan and I met Rick McCallum at a convention once. He was smoking like a chimney, indoors, despite the prohibition of it. He saw my Panavision shirt and asked if I was into film. I told him how inspiring he was and how inspiring "Star Wars" was and he put his hand on my shoulder and said, "Just don't stop shooting, kid."

A cautionary tale

Mitzi's story is a cautionary tale for Sammy. He just needs to keep shooting at that horizon line — top or bottom — but never the middle of the road.

And that's what "The Fabelmans" aims to teach us. To put us in the shoes of those who understand that virus of art and to remind us to keep shooting. But it's also to remind us of those who haven't contracted it, and to see how they can function, too, and to see how difficult life can be for them, living adjacent to those of us with the sickness.

As the film ends, Sammy is at the beginning of his career with a bright future. I hope he's able to keep it, just like Steven Spielberg did. And for those of us who lost sight of our own dreams, let's hope we can take that crashed train and get it back up on the rails.

Let's just keep shooting. I think that's what Uncle Steven would want.