Kamen Rider Black Sun Retells The Origin Story Of Modern Japanese Politics, Just With More Gore

"Kamen Rider" celebrated its 50th anniversary on April 3 2021 by announcing three big new projects. One was "Fuuto PI," an anime sequel to the popular detective series "Kamen Rider W." Another was "Shin Kamen Rider," the newest film by "Neon Genesis Evangelion" director Hideaki Anno. The last was "Kamen Rider Black Sun," a reboot of the classic "Kamen Rider Black." Each pays homage to the past while working to redefine the future of "Kamen Rider" in anime, film and live-action television.

"Kamen Rider Black Sun" was uploaded to Amazon Prime on October 28th, 2022. "Kamen Rider" fans had a tough time finding the series through Amazon's search engine; some resorted to posting direct links to the series via social media so their friends could check it out. (The series is now much easier to find on Prime, thankfully.) "Black Sun" earned a positive write-up on Crunchyroll via tokusatsu expert Alicia Haddick, but has otherwise been completely ignored by the United States television press. This is too bad, because "Black Sun" is a fascinating and unabashedly political superhero epic that's worth examining. Like "Watchmen" or "The Dark Knight," "Black Sun" uses its superhero trappings to comment on recent events. Also, a grasshopper man decapitates a giant spider in the first episode.

Birth of the eclipse

Before there was "Black Sun," there was "Kamen Rider Black." Released in 1987, "Black" broke continuity with earlier "Kamen Rider" series that had aired since 1971. The Riders of the past were nowhere to be seen. The hero "Black," Kotaro Minami, fights an evil cult called Gorgom. Kotaro is a straightforward hero, but the monsters he fights are genuinely scary. Even worse is his stepbrother Nobuhiko, who has been brainwashed to become the terrifying Shadow Moon. Their rivalry was the first in the franchise to pit rider against rider, paving the way for hero battle royale shows like "Kamen Rider Ryuuki." The first episode of the series, which you can watch for free on YouTube courtesy of Toei, is strikingly confident. Its costume designs are excellent, the fighting is frenetic, and the night scenes (filmed in ten whole days) impress even compared to modern tokusatsu series.

"Kamen Rider Black" has serious problems, of course. Its lead writer, Shozo Uehara, left the production early on. Much of the series consists of monster of the week episodes that vary in tone and quality. Shadow Moon, the show's greatest innovation, only becomes a major player in the last fifteen episodes. "Black" aspired to be the darkest, most serialized take on the "Kamen Rider" formula yet made — but it also features a friendly sentient motorcycle alongside episode plots that wouldn't be out of place in "Sailor Moon." So of course, "Black" was a hit. In fact, the series was so popular it became the first "Kamen Rider" to earn a direct sequel, "Black RX." Notorious anime scriptwriter Gen Urobuchi, who co-wrote "Kamen Rider Gaim," credits "Black" for spurring his interest in the franchise.

Humans and kaijin

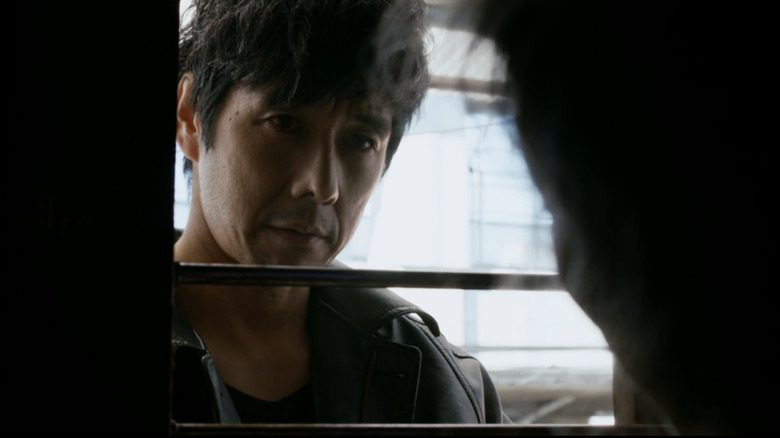

The broad strokes of "Kamen Rider Black Sun" are superficially similar to its predecessor, "Kamen Rider Black." The story begins with two boys, Kotaro and Nobuhiko, who are transformed into monsters and must fight each other to the death. They are once again threatened by the Gorgom cult, which includes many characters fans may remember from "Black." Yet "Black Sun" is a different animal than "Black." Kotaro and Nobuhiko reunite in the very first episode, rather than the 34th. They initially transform into horrifying grasshopper men, rather than the stylish masked heroes of "Black." Not to mention that while Gorgom remains a cult, it is now also a political party.

The first big change that "Black Sun" makes to "Black" is how it characterizes mutants, or "kaijin." In "Black," kaijin are devoted cult members transformed by Gorgom to take on the characteristics of plants and animals. They are solely villains that Black must defeat. In "Black Sun," kaijin are everywhere. They are indistinguishable from humans so long as they do not transform. Even so, they are persecuted by hate groups whose language evokes xenophobic rallies that still occur in Japan today. In short, "Black Sun" is an "X-Men" story, similar to 2020's similarly pointed anime series "Brand New Animal."

Not one gram of difference

Just like "Brand New Animal," "Black Sun" comes with built-in limitations. Real minority groups do not transform into super strong animal people when they become upset. Neither can they regenerate their injuries by consuming Heaven, a superfood whose origin you'll almost certainly guess before it's revealed. Even so, I was surprised by how many big swings "Black Sun" makes within its format. This is an "X-Men" story that distrusts both politicians and police. Rather than superhero fights, the heart of the series lies in youth activist Aoi Izumi's struggle against a cynical right-wing government led by off-brand Shinzo Abe. "Black Sun" even finds (limited) roles for people of color in Aoi's activist movement, demonstrating solidarity between kaijin and Japan's ethnic minorities.

"Black Sun" is at its best when the Gorgom Party is front and center. Like in the original "Kamen Rider Black," Gorgom is the front for a cult that worships powerful Creation Kings. But it began as a group of political activists who fought for the rights of kaijin in the 1970s, and directly inspired Aoi's present-day organizing. Kotaro and Nobuhiko were once part of that movement, only to turn against it after an inter-party schism. From the second episode onwards, "Black Sun" leaps back and forth between the past and future of Gorgom, depicting the absorption of the kaijin rights movement into establishment politics. The series could do more to let the viewer know when it switches time periods, but the 1970s costuming and set design is consistently great.

The past and present of Gorgom

"Black Sun" unabashedly draws connections between its narrative and real Japanese history. Gorgom's beginnings as a nexus for student activists and workers evoke the Zenkyoto movement, the "All-Campus Joint Struggle League." Its assimilation into establishment politics, and the bitterness with which Kotaro sees the current political status quo, reflects the failure of Japan's left to seize the levers of power. The Japanese government's deal with the kaijin ties directly into its ambitions of military expansion, which drove real-life protests through the '60s and '70s. The villainous prime minister, Shinichi Dounami, might as well be Japan's former (assassinated) prime minister Shinzo Abe, even having a grandfather accused of war crimes. You could even argue that Dounami's connection to Gorgom, intentionally or not, is reminiscent of Abe's ties to the Unification Church.

"Black Sun" is not the first Japanese superhero series to grapple with politics. "Concrete Revolutio," the anime passion project of former tokusatsu writer Sho Aikawa, imagined a parallel 1960s Japan where every character from Japanese pop culture was real. (The series even takes place across two time periods, just like "Black Sun.") "Gatchaman Crowds" theorized how superheroes might change in a world of social media, and its sequel "insight" predicted Trump's election three years before it happened. Like these two series, "Black Sun" is not subtle. If anything, it is even more willing than its predecessors to go for the audience's throat. There are moments in "Black Sun" that directly evoke real-life murder and brutality; whether these scenes are effective or shockingly insensitive depends on the viewer.

This is unforgivable!

Even so, there's something thrilling about seeing a superhero show (and a "Kamen Rider" series, to boot) so willing to challenge the politics of its home country. Marvel movies paper over the realities of drone warfare and American hegemony; even exceptions like "Black Panther" end with an argument for the status quo. The most successful film ever based on a DC character, "The Dark Knight," can be read as an argument for the necessity of the War on Terror. "Black Sun" has the grittiness of "The Dark Knight" but is far more mistrustful. Its sympathies lie not with superheroes or politicians, but with ordinary people navigating a complicated landscape.

So "Black Sun" is a fascinating, if uneven series. But is it "Kamen Rider Black?" That, to me, is the real question. "Black Sun" has much better cinematography, costuming and acting than average for a tokusatsu series. The stripped-back kaijin designs and gross aesthetic have their distinct charms. But "Black Sun" can't help but look poor compared to the best episodes of "Black." Its action scenes aim for realism, but in so doing dampen the energy of tokusatsu. The lack of colors and ugly art direction can't help but evoke the worst excesses of modern DC films. Worst of all, the bike isn't there. Modern viewers might ask why a show for adults should have a sentient bike in it, but the absurdity and pathos of that bike embodies the strengths of "Black." "Black Sun" is a weaker series without those elements.

The tokusatsu spirit

"Kamen Rider Black Sun" was built from the ground up to diverge from the rest of the franchise. Series director Kazuya Shiraishi is best known for violent crime films like "Last of the Wolves." "There's a reason why 'Black' is in the title," he insists in an interview with Tokusatsu Network. His ally, legendary special effects designer Shinji Higuchi, says that "I want to start from scratch and consider why [monsters] exist." Together they reimagine the melodrama of "Black" as an epic political drama and crime thriller, a world apart from the toy-centric realm of mainline "Kamen Rider" titles. Yet the harder "Black Sun" works to differentiate itself from its peers, the deeper it sinks into the quicksand of genre.

That said, I can't help but admire "Black Sun." "Kamen Rider Black" dared to imagine a world free of the restrictions of earlier "Kamen Rider" series, and found an adoring audience even if it couldn't quite go all the way. "Kamen Rider Black Sun" fails to capture the exact appeal of "Black," but is similarly ambitious in its efforts to create an entirely new kind of "Kamen Rider" story. At those moments when its reach exceeds its grasp, "Black Sun" channels the tokusatsu spirit: To accomplish the impossible with meticulous craft and such confidence that the audience cheers even if you fail.