How Wes Craven Accidentally Fell Into A Career Of Making Horror Films

Director Wes Craven (1939 – 2015) changed the face of horror three decades in a row. In 1972, he pushed the genre toward a bleaker, harder-edged tone with "The Last House on the Left," a grindhouse remake of Ingmar Bergman's 1960 film "The Virgin Spring." In 1984, he introduced the indelible pop figure Freddy Krueger into the gestalt with "A Nightmare on Elm Street." Then, in both 1994 and 1996, he openly dissected the relationship horror audiences have with the genre in "Wes Craven's New Nightmare" (for horror authors) and "Scream" (for teenage fans).

Craven never intended to become a horror filmmaker, or indeed even a filmmaker at all. In college, Craven studied psychology and earned a Master's degree in philosophy. The first leg of Craven's professional career was in classrooms, and he taught many students throughout the 1960s. It was only when teaching jobs dried up that Craven turned to filmmaking, initially of pornography. In the documentary "Inside Deep Throat," Craven admitted to making several porn movies, although he will never, ever say which ones or what is screen name was. He did, however, claim to have worked on Gerard Damiano's infamous 1972 film "Deep Throat" in some capacity. The same year, Craven would also make his first horror feature.

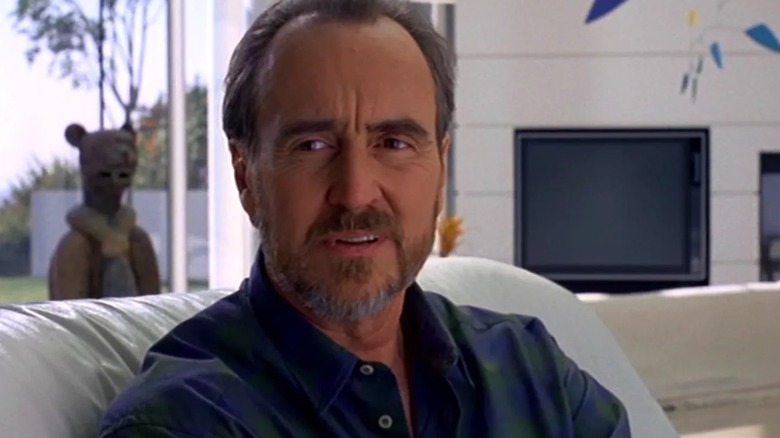

In a 2015 interview with The Front, Craven's last before his death, the nightmare maker talked about his early days as an arts enthusiast, his Baptist upbringing, and how he kind of stumbled into filmmaking. He revealed that he always had an interest in horror, but it was by no means an obsession.

Couch surfing through the summer

Craven, as so many people have experienced, went through a painful bout of unemployment early in his career. He would fly back and forth between New York and Los Angeles, hoping to land a nice teaching gig on the east coast. The clock was ticking, as Craven was only going to be paid through the summer (a bonus from his old employer, he explains, because he had a wife and child). It was when he was sleeping on his brother's couch in New Jersey that an opportunity opened up. Not a job, but a formative experience that would set Craven on an alternate career path. He learned to edit. Craven said:

"One of my students told me he had a brother in New York who was making movies, something called "Industrials" for IBM. At the end of the second summer, still without a job, I went and saw him. He told me he didn't have a job for me but he could show me what he was doing. There, he taught me the basics of editing. I just sat by him and sucked it all up. His name was Harry and my student's name was Steve Chapin, and it was two years before he became the folk singer Harry Chapin."

Harry Chapin, who released his debut album in 1971, might be best known for the hot song "Cat's in the Cradle." If you want to make a middle-aged man weep like an Oscar winner, play him "Cat's in the Cradle."

The teacher becomes the student

So there was Craven, a 30-year-old professor with a Masters in philosophy, sitting next to two younger guys in an analog editing bay learning all about the way industrial films were put together. Craven's drive toward filmmaking wasn't driven so much by a need to tell stories as a practical job he had the skills to execute. Sometimes, all it takes is getting good at something, even if it's something you're not wholly interested in.

While learning about editing, Craven finally caught wind of a job — a very bad one — that he was forced to take. He essentially had to step into a position usually reserved for high school students. In so doing, however, Craven met the right people. With some luck and passion, he climbed the ladder quickly. Teaching, it seemed, would have to wait. Craven said:

"I was watching him, learning, and the guy who ran the post-production house that Harry was running a room in fired his 16-year-old messenger. He asked Harry if he had anyone to fill in and I said I would do it. He said, 'Are you the guy with the master's degree who is a professor?' It paid something ridiculous, but I agreed. That was my first paying job. It was the ticket. Once you get your foot in the door you can show your skills. I worked my way up, first learning post-production, then I moved into synching up dailies and working in editing rooms."

Craven essentially broke into the industry the way any ambitious post-production intern or hopeful office-bound teen dreams to. Work hard in a peripheral field, and soon you'll move up. That's what happened next for Craven.

A run-in with Sean Cunningham

Craven, to skip ahead a moment, would create Freddy Krueger in 1984. As it so happens, one of the people Craven floated into the orbit of was a horror producer who, years later, would create a scary figure who would end up — in 2003 — appearing in a feature film with Freddy Krueger. This person needed a director and editor of a low-budget horror movie that he intended to produce. Craven was coy for a moment, but eventually revealed that man to be the inventor of Jason Voorhees. He said:

"I met a guy whose tiny little film I worked on, got an offer by some theater owners to make a scary movie. He told me to go write something scary, and if they liked it I could direct it. He owned a little Steenbeck editing table, he said, so I could cut it on that and direct it; he'd produce it. That was Sean Cunningham who did 'Friday the 13th.' That's how I got started making scary movies. It was 'The Last House on the Left.' Before that, I had no impulse. I immediately tried to move away from it."

So Craven had made some adult features and a horror movie just to make ends meet. Craven admits in the interview that he finds "The Last House on the Left" to be particuarly nihilistic and brutal, even for his own taste ... and he wrote it! Looking into the abyss wasn't something Craven ever wanted to do, as he seemingly never wanted the abyss peering back.

Horror as therapy

Craven admits he didn't quite know where the brutality of "The Last House on the Left" came from, apart from its Swedish source material. He posits, however, that — after talking to other filmmakers in the horror scene — that the genre was made as a form a therapy. Craven had a very strict Baptist upbringing, which, he theorizes, instilled in him a fear of Hell and sin. That, he says, must be where "Left" came from. As he said:

"[People ask] 'Where does this come from?' I don't know. Now I know most of the major guys and girls who make horror films and they are a jolly bunch. We've all talked about it amongst ourselves and we were scared in school or bullied or whatever, or had scary fathers. It's partially a way to immune yourself from terror and fear. And I'm sure there is a certain amount of anger and even rage in being raised in a way that says half of the great sources of inspiration and joy in life are sins and you burn in hell forever. I'm sure that had done a lot of psychic damage."

Craven, at the end of the interview, was lackadaisical about his legacy. He was demure about his influence on the genre, and still seemingly felt that he was more a philosophy man than a "horror guy." But, even if Freddy Krueger was to be listed first in his obituary, he knew that it touched a lot of people. At the end of his life, Craven was pragmatic and humble.

"I wrote and directed it, and that's what I did. A lot of people love it, a lot of people got inspiration from it, I got a lot of letters from young women saying I empowered them. It could be worse, you know?"