Inherent Vice Ending Explained: Lost My Train Of Thought

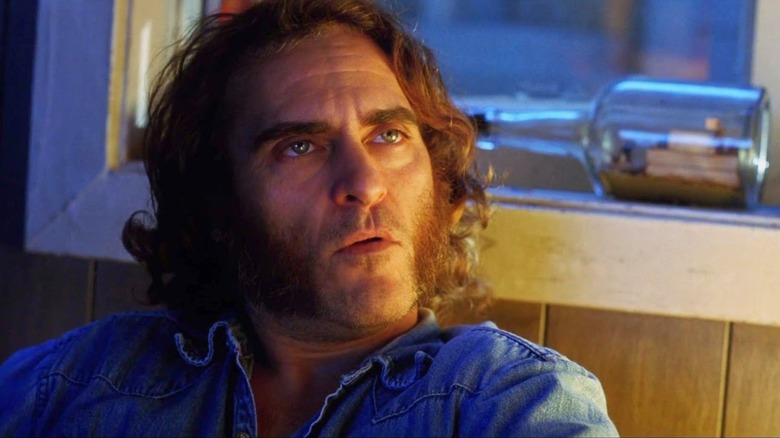

Based on the labyrinthine and deliberately oblique 2009 novel by Thomas Pynchon, Paul Thomas Anderson's 2014 film "Inherent Vice" retained the book's convoluted opacity but added a stoner's whimsical lack of focus. The film's main character, "Doc" Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix), is ostensibly a private investigator, but he's typically too stoned and/or distracted to focus on the case(s) at hand. As the film is set in Los Angeles, Doc is seemingly lost in multiple Raymond Chandler novels simultaneously. In one scene, it will take the film's mostly off-screen narrator Sortilège (Joanna Newsome) to contact him psychically — stoners share a psychic bond, it seems — to remind him that he's lost the trail and to pick up the pace. It's fitting that the film is 150 minutes. It takes the slow-moving Doc that long to make it through the machinations of the plot.

And, at that, the plot is incidental. "Inherent Vice" is, kind of like "The Big Lebowski" before it, a collection of vignettes constructed around people who are just feeling their vibe, man. Some of them are aggressive, some are docile, some are oversexed or strange, but they all are slaves to their appetites.

"Inherent Vice" is set in 1970, a post-Altamont time when the idealism and "be you" ethos of the hippie movement was staling into the cynicism and "f**k you" ethos of the disco era. In a way, "Inherent Vice" is a paean to a lost era of hope when it seemed that smoking weed, making art, and dreaming were enough to change the world. In a way, for Doc, that kinda, sorta, maybe proves to be true a little bit in a small way, kinda sorta. Maybe.

Huh?

The plot of "Inherent Vice" is difficult to surmise even among repeat viewings. As clearly as possible, here's the simplest way to describe it: Doc's ex-girlfriend Shasta (Katherine Wateraston) hires Doc to investigate a wealthy real estate developer named Mickey, whose wife may be trying to have him illegally committed to an asylum.

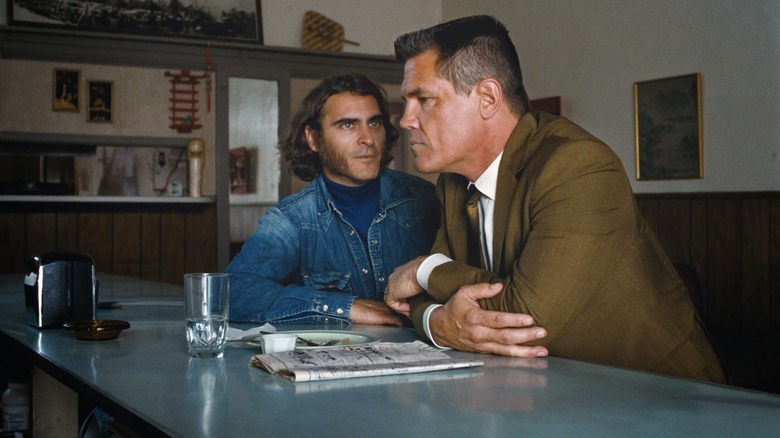

Meanwhile, Tariq (Michael K. Williams) hires Doc to find a man named Glen, a white supremacist, a debtor, and a bodyguard of Mickey. This case leads him to visit one of Mickey's developments, only to find an illegal brothel run by Jade (Hong Chau). There, Doc will be knocked out, only to wake up just outside ... handcuffed to the dead Glen and surrounded by cops. Law and order are represented by the hippie-hating block of wood Lt. Christian F. "Bigfoot" Bjornsen (Josh Brolin).

Then, Hope (Jena Malone), a former heroine addict, hires Doc to find her missing husband who is presumed dead, but whom she insists is alive.

There is also a drug smuggling ring called the Golden Fang. Martin Short is a randy dentist who is involved in some of the things or some other things perhaps. Reese Witherspoon shows up as D.A. that Doc is having an affair with. Benicio Del Toro appears as a guy who hangs out for a little bit. Doc is kidnapped, but flees. Once again, the thread is lost.

The important thing to remember is that Doc and Bigfoot have an increasingly antagonistic relationship over the course of the film, and it will be their conflict that will inform Anderson's entire work. "Inherent Vice" is a battle of a laidback, kind of filthy peacenik and walking, steel-eyed crewcut conservatism. Which one, "Inherent Vice" seems to ask, will have the energy — not the resources or intelligence, just the energy — to culturally prevail?

Wha?

Bigfoot represents the square, cruel "law and order" that Doc seems genetically engineered to avoid. Early in "Inherent Vice," Doc enters a police station, and mockingly hunches into a protective fetal position when a retinue of uniformed cops walk by. The police are the enemy. They are the ones who beat up protestors. Bigfoot is the face of that violence. Tightly wound and buttoned up, Bigfoot cannot abide the chaos and apathy that Doc personified. In what might be considered the film's epilogue, Bigfoot visits Doc, who is, naturally, consuming a great deal of marijuana. In a display of what might be solidarity, Bigfoot takes a hit from a joint. Then, in a bizarre example of what might be defeat, Bigfoot tips a giant try of marijuana leaves into his mouth, eating it all.

Doc is baffled by this, as perhaps is the audience. It is, however, the crux of their conflict. The hippies weren't right, but the world was too chaotic and strange to expect and enforce order. In his own way, Bigfoot seems to be admitting, Doc has found the best way to traverse the world. Not that Bigfoot could ever give up on his in-born instincts for gruff, bullying law enforcement; during the climax of "Inherent Vice," a frustrated Bigfoot plants heroin in Doc's car.

Doc, taking the world in stride, gives it back to drugs dealers in exchange for a hostage.

Doc might be compared to Jeffrey Lebowski from his eponymous film. Doc, however, is a man of action. Someone who loses the thread, but still has a streak of agency. Lebowski only knows creature comforts.

Howzatagain?

As for the conclusion of the plot, the narrator helps. Doc, near the end of "Inherent Vice," is more or less told in plain English that he needs to wrap up, well, something. If not, the narrator seems to imply, the movie he's in won't have a satisfying conclusion. Doc elects to wrap up the most emotional storyline: Hope's. She was the former drug addict who longed to reunite with her husband. The missing real estate tycoon is found, but that ending wasn't so great. Glen was located, dead, much earlier in the story, so that wouldn't provide a proper denouement. So it must be Hope's story that will satisfy. "Inherent Vice" seems to be working out the machinations of its own screenplay in real time.

Doc locates the missing husband (Owen Wilson), uses the drugs Bigfoot planted in his car as a ransom payment, and presumably Hope with have a rudimentary family back. In the film noir sense, the good were rewarded and the wicked were punished. This is as palpable a solution that a scattered film like "Inherent Vice" can provide.

Some audiences may not find this ending to be satisfactory, so baffled they might be by the film's many, many wriggling loose threads and disconnected vignettes. Some critics weren't kind because of that. Dan Callahan at The Wrap felt that Anderson had lost himself to a weary sense of cinematic duty, rather than lose himself in the joy of the craft.

In a logical, analytical sense, "Inherent Vice" falls flat. As a half-remembered essay about the power and pervasiveness of human folly, "Inherent Vice" is first rate.