What The Sandman Looked Like Before The Visual Effects [Exclusive]

When making a television series, trying to do justice to something as beloved and as iconic as "The Sandman" comic series is undeniably a daunting task. For those unfamiliar with the comic, "The Sandman" was the blueprint that goth teens in the early '90s based their entire world around: it ran from January 1989 to March 1996. Written by Neil Gaiman with artwork by several talented artists, every panel is dense with spectacle. The series follows a family of metaphysical entities that personify several aspects of our reality. The main character Dream, aka Morpheus, leads us through a tale that spans the history of humanity and is as poignant as it is horrifying.

To bring stellar artwork and timeless characters to life on screen, Netflix needed a magnificently talented visual effects team and someone to lead them with skill and passion. Netflix hired VFX Supervisor Ian Markiewicz, known for his work on "Agent Carter," "Black Sails," and "The Flash." I had the pleasure of speaking with Markiewicz about the show's design, receiving an inside look at the tremendous effort it took to make each scene worthy of "The Sandman" legacy. Markiewicz and his team used a mix of practical effects and CGI to translate the comics into a living, breathing world filled with beauty and terror. Below, I've collected some stories of how he did just that.

The Palace of Dreaming

"The first thing that we were tasked with was figuring out Dream's palace," Markiewicz said. "That becomes a real interesting question where it's like, 'Okay, so this is a palace of the dreaming.' It's supposed to be something that is, in my mind, a mosaic of all different forms and things and shapes. In the comic books, there's a wonderful progression — depending on Morpheus's mood, that palace is a reflection of that, or where he sits in time and space, that palace is a reflection of that."

Markiewicz took inspiration from a sculptor, Kris Kuksi, to design Dream's palace. "He does this amazing thing where he takes all these different bits of iconography," he continued. "So they could be these amazing sculptures. So it's like a Michelangelo sculpture. Then he mashes it with all this other stuff that he finds that are kind of parts of online little pieces. What it felt [like] to me was a dream mosaic, where it was, if we think of these building blocks of this structure as the dreams of not only humanity but also of anything that has a consciousness. That's one of the things that's so fascinating about Sandman in terms of [its] comic book mythology. It's not just humanity that dreams: it's anything that dreams is reflected in the dreaming."

Turning a cathedral into a throne room

Very few scenes of "The Sandman" were filmed in a full-green box. Shooting at real locations was a priority, as it contributed physical and spatial references for the cast and crew. "It gives us, as visual effects artists and technicians, a huge amount of information to go on when we've got photography on the plate," Markiewicz said. "It means that we can usually do that much better to make sure that those integrations are seamless."

For scenes in Dream's throne room, the show was filmed on-location at Guildford Cathedral in the UK. "A very big decision that was made early on, was to try to get a real space to shoot Dream's throne room. We knew that the throne room was going to have to be heavily augmented. Any reasonable person might say, 'Okay, this should be a fully virtual environment and we should shoot this on a full green screen stage or on an LED array volume, et cetera — if that proves cost-effective, and worthwhile for the production.' I was really opposed to that idea. I felt like, for me, what I have experienced time and time again is despite everyone's best efforts — and that it goes for myself and the entire crew and the cast when we're working in green boxes — I do feel like there is a loss in the artistry of the filmmaking craft."

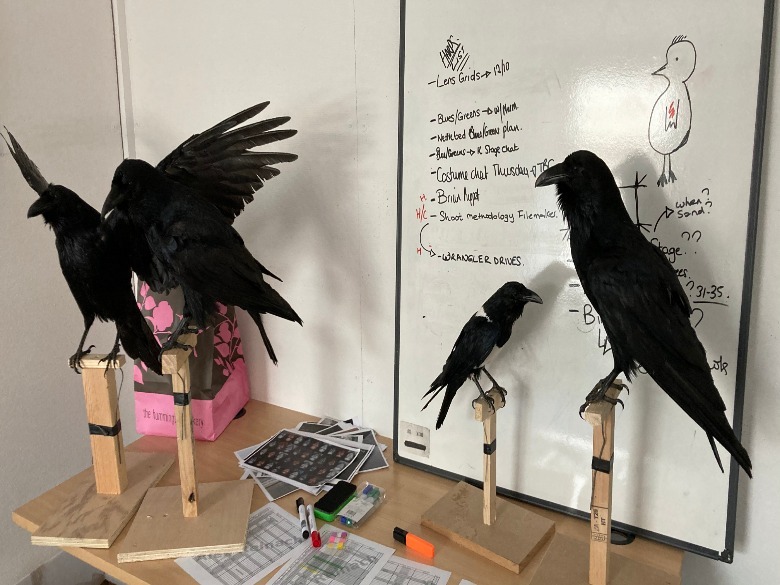

Matthew's design came from real birds

Markiewicz noted that Matthew (voiced by Patton Oswalt) was one of the more exciting designs the SFX team tackled. "Our objective was to make a completely photo-real raven that was a human trapped inside a bird with all of the physiology of a bird, but with the mind of a human being and the ability to talk. What we were able to achieve with him, whether it be the night wind blowing through his feathers, and curling them back — whatever the case may be — the very particular performance quirks that are part of that character, but still I think are successful in feeling very birdlike. I think that we, as a team, were all pretty proud of what that looked like."

According to Markiewicz, about 95 percent of every shot of Matthew is full-CGI. However, the production used live birds on set to provide references for the CGI team to work with during their creation process. Matthew and Jessamy were brought to life with the help of 3 trained birds each.

"So in visual effects, we would take that reference and use it as a sort of goldmine of performance, reference lighting, reference of everything. Take all the best moments across 15 takes and figure out how to generate a character that then had Patton Oswalt's personality as part of its overall behavior classification, and basically recreate that bird."

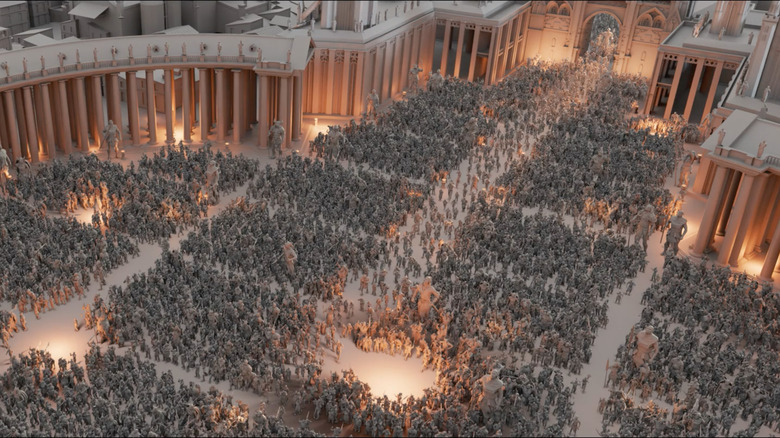

Lucifer's palace

"When someone says, 'Okay, design Lucifer's palace,' it's terrifying," Markiewicz noted."You're like, 'Okay, well I don't know how that's ever going to feel satisfying to anybody.' But that's a fun challenge creatively to then set out, say like, 'Okay, well what do I think this should look like? What reference images do I gather to start that process?' A decision that we made — that I was a little worried about was going to be a little bit of a third rail, but I think everybody understood the intention behind it — was that we deliberately modeled the back of the palace, in terms of the balcony, after St. Peter's square at the Vatican, which was not intended to be any sort of tongue-in-cheek statement about Catholicism at all. It was about Lucifer being a fallen angel. Lucifer is shaping this space as they see fit. I thought it was a really interesting angle into the psychology that allowed for some sense of that iconography."

To make the most of this ironic allusion to a real-world location, the VFX team intentionally played off the expectations of that space. They adjusted the height of the balcony, changed the sculptures, and added small details that evoked hell's version of this iconic space. "I also felt like it was in keeping with Neil's approach to how he finds these direct cultural touchstones, and these real religion, myth, fable. These are things that are Sandman. This is, to me, why the comic is so interesting. [It's] how it's able to gather and recombine all of these amazing literary references and architectural references."

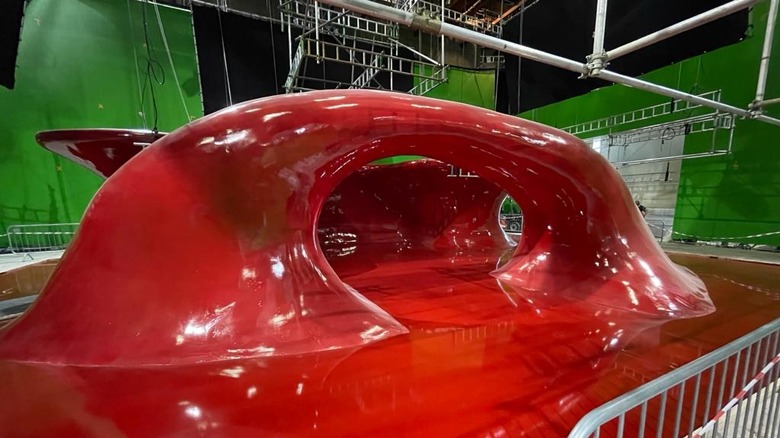

The Threshold of Desire

The Threshold of Desire was painstakingly carved out of foam blocks by production designer Gary Steele ("Luther," "Outlander") "It's not easy to move onto an existing cathedral... So, there was always this discussion of, 'Can this be a real place?' If it can, let's start with that, and that will be our first ask. If it can't because of any number of reasons — it's too far away, geographically, it's too expensive, it doesn't give us what we need — can we then build it? Then, it became a question of, 'Well, Gary... what can we make on stage to make this work?' So, the Threshold of Desire is a good example where Gary was able to build a section of that set, which is this beautiful curved arch and curved back area where sigils hang in terms of the gallery."

In the original comic, Desire's dwelling isn't well defined: the walls are dark, allowing the reader to focus on the characters. This artistic choice in the original work left space for Steele to design a set reminiscent of something akin to Roger Dean's architecture, as it would look if carved out of a human heart. By giving the interior a more defined look, it becomes luxurious and sensual, yet slightly disturbing — an absolutely perfect domain for Desire.

Gregory's puppet

The scene where we meet Gregory the Gargoyle is one of the saddest in "The Sandman" television adaptation — despite the brief time viewers have with him. The visual effects team had the challenge of not only crafting a believable gargoyle but finding a way to get the audience to quickly connect with Gregory.

"For us, we knew that was always going to be full CG, Gregory. Of course, he would have to be, but it wasn't just going in, and shooting after with the tennis ball... Brian (Fisher) was our puppeteer and he did a phenomenal job of giving that character personality, even in the plate photography passes. So if you look at the before and actors of those sequences we have, it looks goofy, but we've got Brian in a full-green suit, but he has a 3D printed head of Gregory, which our props department was able to provide, which was awesome. So we said, 'Here's the model. Here's what we're going to build digitally.' We gave them that VI, and then a week later, they came back with this wonderful stuffy head for us."

"Then we had Brian who was able to go away and think about what that character's performance would be. And then on the day, you can feel that performance with the actors. I think that even [when you're] watching a guy in a green suit, it still has emotional potency and resonance. I think the actors are responding really well, and you already feel that connection. For us, that groundwork was, once again, laid on set even before that well into prep in terms of all the pre-vis, all the sort performance stuff that we did with Brian."

Gregory the puppy

Once the recording session with the actors on set was complete, the special effects team worked on finding ways to make the audience fall in love with Gregory.

"In the later stages of that development, it was all about just trying to find things that I'm a softie for. So I'm a total dog lover, I've got two dogs. I spent a lot of time studying one of my dogs who's a German shepherd mix and tried to get a lot of the same kind of gestures, a lot of the same kind of eye movements... So it's no accident that he's very doglike in his behavior.

"I think that we lean into... any soft spot that anybody has for an animal. I think that's why those scenes are potent. Again, I'll credit the artists who were executing that, because that was one of those things where we would talk about performance, talk about all these things, but when we'd start seeing these full renders come back, it was like, 'Oh, my God, he's there. He has a personality. He has warmth. He is communicating even though he's not speaking.'"

Goldie's unique texture

Goldie provided a different challenge for the SFX team of "The Sandman," who decided to match the creature's appearance in the comic book series. Markiewicz focused on getting Goldie's skin coloration and textures right to make the baby gargoyle as realistic as possible.

"Like yes, he's Goldie, and yes, he's gold. But we need to look at wildlife and need to look at reptiles and see how, even if something is one color, there is a variation over different parts of the body, and how it wears different areas of skin and scales. How they stretch so that it doesn't just look like he's been coated in gold paint. In our first early, early draft of him, he looked excellent. But that's exactly what he looked like. He looked like he was a cute little toy that was dipped in gold paint. I think that finding the difference between a toy dipped in gold paint and a cuddly little gargoyle baby character, was the artistry of that particular adaptation. Yes, he is very much one-to-one, but we still had to figure out how to give him life in a way that made him feel authentic to the show and faithful to the books."

Dream's sand magic

Dream has a bag of magical sand that he uses in several ways — puts people to sleep, transports himself, and sprinkles it into everything he does. Markiewicz revealed that in the early stages of filming the team used six different piles of sand with various combinations of color, glitter, and details that the effects team could manipulate on film. But the practical effect never quite had the elegance they wanted.

"It would be a really, really good reference, but it would never do exactly what it needed to do," he shared. "No surprise. We didn't expect that it would, but just those very subtle art direction things, any one of those, and the same is true for the reabsorption of Gregory in terms of what is Dream stuff in our show." When Gregory dissolves, Markiewicz didn't want to show the viscera of the character but instead conveys the idea that a dream doesn't have mass. He described Gregory the gargoyle as hollow like a chocolate bunny. He used that imagery to guide how the sand would move. "When that facade starts to crack and separate, and then that then separates into smaller individual component granules that hopefully then recombine into this sand stuff — that became a little bit of the language of figuring out how that would be."

Wrangling 1,000 cats

In the final season 1 episode of "The Sandman," there's a bonus story that covers the dreams of cats. To give the episode a unique feel and look, Markiewicz brought on the artist and filmmaker Hisko Hulsing. "Hisko was somebody who Alan (Heinberg) and I found online based on some of his short films from several years ago," Markiewicz said. "Hisko's now doing "Undone", a series for Amazon. So he's since gone, and blown up, and doing this style. But it was a really interesting art style that we hadn't seen before, where it was this really cool blend of live-action photography that was then rotoscoped, but then he oil paints. So, the backgrounds are physical oil paintings that artists paint as real canvases, these large, big canvases. And then there's an additional painting done on top for the characters themselves."

Of course, real cats are notoriously hard to direct, so a company called Untold ended up creating all of the cats with CGI and then passed the footage to Hulsing to rotoscope the work and then paint. Under Hisko's oversight, the independent production company Submarine handled the oil painting and compositing. "In Hisko's studio... He's got 40 or some of these massive canvases, which are amazing, and then additional hand paintwork on top of that. I love the fusion of what the technology was able to do for that particular sequence. I just thought that the way that they handled that was so interesting."

Over 800 crew members worked on The Sandman

The amount of work that goes into a show like "The Sandman" is staggering. The production had around 12 companies, including ILM, Frame Store, ILP, Rodeo Effects, Untold, One of Us, Union, CBFX, and Resonance. Approximately "The Sandman" had 800 staff members when counting its production and support management teams.

As Markiewicz noted, many times the vast number of individuals who work on these shows are invisible to the public. But without them, our gargoyles would be nothing more than tennis balls on a stick and our dreaming cats would snub the script for a nap.

"I think that recognizing the sheer volume of individuals who were working on this for a very long time and spent a lot of energy trying to come to something that they were excited about and passionate about. I think that in our visual effects field, that recognition is too few and far between... To the credit of those craftspeople, and to those companies... I hope we did it justice."