'Us' Movie Explained: Exploring The Biggest Questions And Craziest Twists In Jordan Peele's Film

(Us, the new horror film from Jordan Peele, is in theaters now and it's the kind of movie that demands a conversation. So Jacob Hall and Ben Pearson are here to do that. Let's unwrap this movie's mysteries, shall we?)Jacob: So you've just seen Jordan Peele's Us. And you have questions, right? Trust us – we know the feeling. Peele's follow-up to Get Out is a shotgun blast of ideas smuggled into a crowd-pleasing horror movie. Its themes are troubling. Its concepts are tricky. Its perspective is deliberately obfuscated just enough to demand conversation and debate, because the text itself isn't going to offer up easy answers. That's why we're here. Not to fully "explain" Us, a film that defies categorization and easy definitions, but to dig in, to grapple with it, and hopefully inspire you to continue this conversation with your friends after you see it again. Because we're all going to see it again, right?Ben: I know I will. In this piece, we'll present a recap of some of the most head-scratching aspects of the film and try to dig into the thematic meanings behind them – or rather, some possibilities about their thematic meanings. We've included several quotes from Peele throughout, but he's (rightfully) been cagey so far about definitively explaining...well, just about anything. To be clear: this film isn't a puzzle to be solved, but it was specifically designed to spark conversation. So let's dive in, but be warned: there are major spoilers ahead.

Who Are the Tethered?

Jacob: Peele's screenplay deliberately leaves many questions unanswered when it comes to his main villains. Understanding the exact hows and whys of these doppelgängers is shuffled into the corner, a beguiling mystery that exists to fuel the threat our heroes face, create a set of terrifying villains, and present tough questions about how we, as a species, actually operate. What we know for sure is that "the Tethered" are the result of a massive government program of some kind, conducted in miles and miles of concrete tunnels underneath the United States. Everything has that sterile, blank look of a laboratory, but the connection between the Tethered and those above suggests something more...occult.

In fact, it's said this experiment was all about controlling the human soul (shades of that infamous mind control/fluoride conspiracy theory mentioned earlier in the film), which suggests an experiment that is attempting to meld science and mysticism. But are they clones? If so, where did they get the DNA? Are they some kind of occult copy, like a VHS tape recording of the proper high-def broadcast? If so, how has this power gone unnoticed? Peele goes out of his way to make sure we don't know more than this. It's intentional. Those who started this experiment abandoned it – and the millions of subjects – underground decades ago. The only person who lives there after experiencing life above has lost her mind. Part of the terror of the film is knowing that these gaps will probably never get filled.

What else am I missing, Ben? I know people from my screening and yours alike feel like they missed something important here. Is it that deliberately opaque?

Ben: I think you covered the basics. For most of the film, we're kept in the dark about who or what the Tethered are. But late in the film, Adelaide and Red – the two characters played by Lupita Nyong'o – come face to face and the explanation is laid out like Goldfinger telling James Bond about his evil plans. Scenes like that can be tough to follow sometimes, and I think even viewers who have been fully engaged up until that point have found their eyes glazing over a little during that scene.

Naturally, when a movie presents the idea of an entire society living in underground tunnels, it's going to raise some questions for literal-minded viewers. But we'll talk about that in a minute. Before we get there: Jacob, what do you think Peele is trying to say with the Tethered?

What Do the Tethered Represent?

Jacob: Oh, boy. Here's where we have to start wading into the murky swamp of metaphor Peele has laid out before us. I think everyone is going to have a different read on what the Tethered represent and what their mission means. But that's part of the fun, right? I like that there are no hard truths presented here – only an opportunity for conversation. With that said...the Tethered are totally a metaphor for the forgotten people from the forgotten corners of America, right? Your own personal politics may inform where that forgotten corner is and what kind of person it represents, but the allegory feels unmistakable.

We'll dive into more details as we get more specific, but this is a giant, coordinated uprising of people who have been literally left underground by the government, ignored by the social safety net, and forced to watch as people just like them prosper above. And there is nothing they can do about it. There is no way up. Literally. Not until a leader arrived to help them rise up. It's an awfully malleable metaphor, so much so that Peele has already made it clear that Us is not explicitly about race. His goal with casting black actors in Us, he said, was more about representing talent that Hollywood often ignores, overlooks, and misunderstands. Then again, that in of itself is a political act:

"Obviously, my first film had a black lead and it was very much about race, but I think it's just as much of a statement to make a horror movie with a black family at the centre of it and to just have that be so."

Anyway, the Tethered are an unsettling stand-in for Americans who feel wronged and angry and want to shock the system. Ben, I know you followed this through-line to a completely different endpoint than me, but do we agree on this much?

Ben: I think so, yes. Here's my overarching take on Us, the foundation from which the rest of my thoughts are built: I think this is one of the first overtly political mainstream studio movies of the Trump era. We've been pointing out political references in dozens of movies over the past couple of years partially because we've been constantly inundated in the political news cycle, but many of those films were in some form of development before the 2016 election. That's not to say that a film like Black Panther, for example, didn't feel strikingly resonant at the time of its release, but Us was conceived, written, and directed after the most recent presidential election.

On a recent episode of The Big Picture podcast, Peele said:

"With Us, it wasn't until I realized that there was another suppressed piece of [cultural] conversation that I could acknowledge with this movie that I realized I had to make, and that suppressed piece of the conversation is our inability to point our finger inward at us, at our faction. Be it our family, our country, or even us as individuals, our part in it. We're so trained to point the finger outward...for the past year and a half, I've been on a 'them, them, them' mentality the same way the people that I think are wrong [have been]. Whether I'm right or wrong doesn't matter – we all have to soul search and figure out what our part in evil is."

I think The Tethered represent the modern Republican party. That sound you hear is many people angrily clicking away, but follow me on this: they're cloaked in red (the color associated with Republicans), they're a united front during a time when Democrats are quibbling among themselves, and as you mentioned, they feel wronged and angry. When asked who they are, Red answers, "We are Americans." The Tethered have been there all along, and they look just like we do. During that big Bond-style exposition dump, Red says that the scientists who created The Tethered "forgot about us," reflecting the fears of white rural Republican voters in coal country. There's a huge visual cue in the film that lends the most support to this read, but we'll get to that shortly.

The Final, Tragic Twist

Jacob: I know the final twist in Us has proven divisive amongst those who saw the film early, but I love it. And I love it because it's a big twist that manages to be genuinely surprising, fuel the larger themes of the film, and force you to re-examine earlier scenes in a context that transforms their horror into tragedy. So let's address those one at a time.

First, that twist arrives and it shocks you and then you think about it and yeah, it's airtight. Nothing in the movie feels like a cheat once you know that Adelaide and Red switched places years ago and have been living each other's lives. Like the best climactic twists, the ones that serve as the final exclamation point to the movie, it enhances what came before and never diminishes the drama. Good stuff!

Second, a Tethered switching places with her above-ground counterpart and thriving in her life adds a sobering wrinkle to the entire mythology here. We see the Tethered as blank zombies, these approximations of human beings who don't belong in polite society. They are the other. But when a Tethered steps into our society, when she is given every opportunity an above-grounder is given, she achieves it all: she's a remarkable dancer, she marries the man of her dreams, and builds a wonderful family in a comfortable middle-class existence. She was given the opportunities purposefully denied to the other Tethered. She just needed the privilege that so many millions of Americans take for granted.

And finally, how deeply sad are the early scenes between Adelaide and Red once you know the truth? What previously looked like an anxious woman battling PTSD while being menaced by a killer sociopath becomes something profoundly tragic. We realize in retrospect that we're watching a guilt-ridden woman, waiting for the day when her past sins would catch up with her, face down a counterpart who is rightfully seeking vengeance against the person who destroyed her life. And yet, we know "Adelaide" has used her privilege well. And yet, we know "Red" would have also thrived if she was allowed to keep her life. They're trapped in a circle of loathing, rage, and fear – that high-concept home invasion becomes something so much more when you know why it's happening. Honestly, I love that Universal is releasing this movie because it means Red can be a classic Universal Monster alongside Dracula, Frankenstein, and the Wolf Man. She certainly fits in with that sad, broken bunch.

What do you think of this twist, Ben?

Ben: On a purely narrative level, I suspected something might be amiss from the first time we see young Adelaide watching her parents in the therapist's office, but then I promptly forgot about it for the rest of the movie and found myself totally sucked into the story until the reveal came. I love that Peele baked this in so you immediately want to see the movie again, and of course the twist makes Nyong'o's performance even more stunning in retrospect.

On a thematic level, I'll admit the ending was the aspect I struggled with the most as I wrestled with whether or not it aligned with my political read. Unwitting or not, Adelaide is a wolf in sheep's clothing, and though the audience has been rooting for her the whole time, the rug is pulled out from under us and we realize the truth is more complicated than we thought. Sound familiar? It probably does to Trump voters who are doing their taxes right about now.

Our Greatest Fear is Ourselves

Jacob: During an audience Q&A following the premiere of Us at SXSW, Peele directly addressed the themes of his film:

"We are in a time where we fear the other, whether it's the mysterious invader who might kill us or take our jobs, or the faction that doesn't live near us that votes differently than we did. Maybe the evil is us. Maybe the monster that we're looking at has our face."

But as we're exploring here, and as Peele himself would later allude in many other interviews, it's hard to come up with one single tidy definition for what's going on in Us. Here's what I like about this quote, Ben: he doesn't specify which side of the coin is intended to be "evil." After all, isn't Red right to seek vengeance? Isn't Adelaide right to grab her one and only opportunity to escape the vicious cycle that has entangled the Tethered? And as the film goes to show, the above-grounders are just as effective at killing as the "barbaric" doppelgängers from beneath the surface.

Americans are their own worst enemies, Us says. And our knee-jerk desire to label good guys and bad guys has created a mess that will take generations to fix, even if we bothered to pause and actually diagnose the rot. Am I making sense? This movie is bending my brain.

Ben: Yep, that all tracks. After getting a glimpse of how the Tethered live below ground, I don't blame Adelaide one bit for making the switch.

Speaking to Fandango All Access, Peele said:

"This movie's about trauma, and generational trauma, and this idea that what happens in our ancestry or what happens the generation before us affects us and sort of trickles down...it's about [how] what we bury deep and try not to face affects the world that we make around us."

The generational trauma he mentions there obviously applies to Adelaide and Red, but don't forget about the Wilsons' daughter, Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph). You talked about above-grounders being just as brutal as the Tethered, and there may be no greater example than Zora, who grabs a golf club and seems to really relish bashing Tethered heads in with it. She's this movie's version of Game of Thrones character Arya Stark – yes, she lost her innocence, but that traumatic event seems to have resulted in her maybe being just a bit too into the whole "gruesome violence" thing. Peele isn't interested in drawing a clear distinction between good people and bad. He knows life is more complicated than that.

The Haves and Have-Nots

Jacob: In the front half of Us, we're introduced to not just the Wilson family, but their friends and lake house neighbors, the Tylers. This other couple (Elisabeth Moss and Tim Heidecker) and their obnoxious daughters serve a dual purpose. Narratively, they give our heroes somewhere to flee, and the arrival of Tyler doppelgängers is the sudden and brutal reveal which makes it very clear that Red's assault on the Wilson house is not an isolated incident (Ben, when I realized the sheer scope of the attack via the first scenes in the Tyler house, I lost. My. Mind.)

But like everything else in the film, the existence of the Tylers is further enforcing what feels to me like one of Peele's most timely social statements. The Wilsons have a comfortable middle class income. They can afford a lake house and a boat. They can go on family vacations to the beach. They're not wanting for anything. Food is always on the table. But the Tylers? The Tylers have more. They have the nicer house, the nicer boat, and the flare gun that Gabe totally forgot to buy. It's a classic case of have and have-nots – someone is always going to have more than you.

In the case of the Tethered, they're the ultimate have-not story. They'll never have a lake house or a boat. They'll never go on a trip to the beach. They're damned to roam their blank hallways, imitating an existence they can only imagine. Dreaming, if you will, of a life they can never obtain. The rich get richer and buy a boat. The poor get poorer and eat rabbits for every meal. The resentment that digs itself in like a ditch between the Tylers and the Wilsons is amplified to horrifying levels with the Tethered. But they aren't going to be satisfied by sniping about it behind one another's backs. They're going up with scissors. They're going to get those boats. They're going to get those houses. Someone can only be deprived for so long before they snap, right?

Ben, I think...I think I sympathize with the Tethered? Or at least have empathy for their plight, even if their methods are, uh, extreme. I know you ended up taking away a far different message from the final scenes of this movie than me (we'll get there!), but am I crazy?

Ben: Far from it. It's easy to sympathize: Red was forced to marry Winston Duke's Abraham, the Bizarro version of his goofy dad character Gabe, and forced to have two children against her will. That shit is dark.

Here's a big part of why I love this movie: your explanation in this section perfectly aligns with your larger read on the film, but doesn't even come close to aligning with mine. But how great is that? It's rare we get to see a mainstream Hollywood film with so much care devoted to its metaphors and symbolism that there's this much room for different interpretations (and I'm sure there are several we're not even mentioning). The last time we got anything remotely close to this was Darren Aronofsky's mother! back in 2017, and that too felt like a huge outlier.

The Escalator

Jacob: I feel like there are certain images in Us that carry a heavy thematic weight and defy the internet's obsessive "everything must be explained or it's a plot hole" mentality. In other words, Jordan Peele doesn't make movies for the CinemaSins audience and he shouldn't have to cater to them. So he doesn't! I want to talk about the escalator, the one that runs down from the funhouse maze on the boardwalk and into the secret Tethered tunnels. Does it make literal sense that an escalator is the only thing keeping the Tethered from escaping? Of course not! Is it the most clever way imaginable to showcase how a system is built to keep people from rising above the station they're born into? Of course it is! One of Jordan Peele's heroes is Rod Serling – he knows when subtlety won't get the job done. Sometimes, you need that sledgehammer.

Were there any specific visual metaphors that stood out to you, Ben? I feel like future viewings are going to reveal so much more.

Ben: That's such an astute observation about the escalator. I caught the fact that there wasn't an "up" escalator anywhere to be seen, but because I had a different take on the whole movie, the larger meaning behind it completely passed me by.

There are some relatively obvious things I picked up on (notice how Adelaide's white shirt slowly becomes more red with blood as the film progresses, hinting toward that big twist ending), but I did notice one metaphor that wasn't visual because it technically happens off-screen. When the Wilsons are watching a news broadcast, a woman is being interviewed and says she's "seeing red" – a phrase associated with anger. The interviewer follows up with her, and the woman clarifies that the killers she witnessed were wearing red, but I don't think that was a slip-up. I read it as a commentary about outrage culture, about how easy it is for us to get angry and point our fingers at the other side without actually doing the work of, as Peele said, examining "our part in evil." There are a couple more visuals I want to talk about too, but we'll get to those in just a second.

11:11

Jacob: There's a great deal of mirror imagery in Us, from characters seeing their reflection in glass to characters literally staring their own doppelgängers in the face. So the Tethered attack essentially beginning at 11:11 at night could, at first, feel like a cheeky continuation of that. Four identical numbers in a row, four members of the Wilson family, etc.

But if you think Jordan Peele is smarter than that...well, you're right. 11:11 is considered significant in New Age philosophy and numerology. Some see it as a warning, a sign that something terrible is about to happen. Others associate it with Carl Jung's theory of synchronicity, which suggests that "events are 'meaningful coincidences' if they occur with no causal relationship yet seem to be meaningfully related." Without diving too deep into this, synchronicity suggests that events can be connected purely by meaning instead of causality. In other words, the things that happen around us aren't always the result of our direct actions, but the result of a shared common purpose or need. (This could explain why certain tropes and concepts recur throughout stories told all over the world, despite massive distances between cultures.) Could it be that the seemingly "random" Tethered attack happens not because of anything the above-grounders did (causality) but because of what they represent (synchronicity)?

But maybe I'm biting off more than I can chew here. There's also a Bible verse that fits this, right?

Ben: Oh wow, I've never heard about the significance of 11:11 in numerology, and I feel like there's enough there for an entire thesis paper on that angle alone. (Have I mentioned I love this movie?)

But yes – the Bible verse. In the opening scene, young Adelaide walks across the Santa Cruz boardwalk and sees a man holding a sign that says "Jeremiah 11:11". Here's what that verse says:

Therefore this is what the Lord says: 'I will bring on them a disaster they cannot escape. Although they cry out to me, I will not listen to them.'

So in addition to that mirror imagery, there's some classic Old Testament doom and gloom here to boot. Two things jump to mind here, and they largely support your read: the "disaster" taking the form of a revolution, and that haunting shot of Elisabeth Moss's Tethered character Dahlia trying to scream ("cry out"), but not having the voice to make a sound.

The Dance

Jacob: Okay. *cracks knuckles* Let's do this. Before we even started writing this article, Ben and I spoke at length about this scene and what it means and how it spirals into the rest of the movie. It could even be the most important moment in the whole story. But Us doesn't make it easy to dissect (which I say with total adoration).

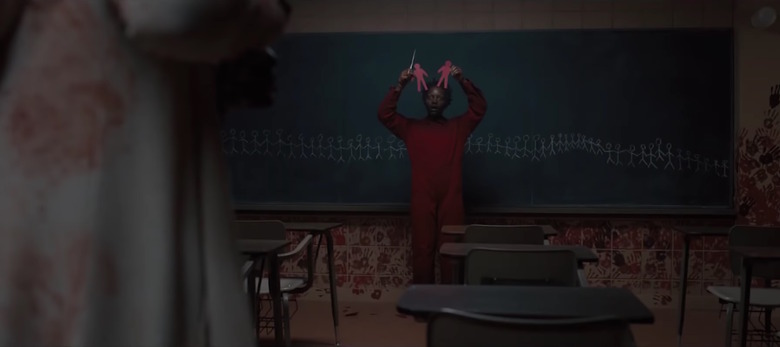

We learn that Adelaide used to dance ballet and that she was promising. A natural. We also learn that the Tethered go through the basic motions of their above-ground counterpart, a pale imitation of life and existence. This means a guy playing a game on the boardwalk will influence his Tethered counterpart to play an imaginary game himself, but without the understanding of what he's doing, of why he's doing it, or even the knowledge of what a game is. But as Red adjusts to her nightmarish existence among the Tethered, Adelaide adjusts to life above ground. She takes up dancing, a suggestion from her therapist, and performs a stunning routine.

And below, in the tunnels, Red imitates it. And it's flawless. And it's beautiful. And it awakens something in the other Tethered. For the first time in their existence, have they actually seen what real life looks like? Have they tasted what it means to be complete, to have an actual piece of the soul they seemingly have to share? If Adelaide can do this above and Red below, what separates them from us? Naturally, this is what gives Red the confidence to lead her assault on the above-grounders. What do you think this scene is saying, Ben? About life? About the soul? I know you mentioned art when we spoke before.

Ben: I really want to watch this scene again, because it seemed to me like Red's dance differed slightly from Adelaide's. That act of independent creation seemed especially important (possibly even symbolizing the power of art itself), but more than anything else in this scene, I was struck by the Tethered's reaction to Red after she finishes. Until that point, we had only seen the Tethered masses hypnotized into repeating the actions of their counterparts, but after Red concludes the dance, the Tethered seem to break from their trance as they gather around her with their arms outstretched, almost as if she's a savior they desperately want to touch.

Remember that Bible verse we talked about? The verses that bookend Jeremiah 11:11 talk about people worshipping false gods, and how they "will go and cry out to the gods to whom they burn incense, but they will not help them at all when disaster strikes." Maybe Red is one of those false gods, a leader whose plan results in untold amounts of death and destruction.

What's Up With the Rabbits?

Jacob: I was prepared to just say the rabbits are hanging around the Tethered tunnels because all scientific experiments begin with rabbits and these rabbits were clearly abandoned by the same researchers who abandoned the Tethered and the rabbits bred like, well, rabbits and became the only food source down there. That's painfully literal, but I'll admit: as much as I enjoyed the haunting imagery of these guys (especially over the opening credits), any additional meaning flew over my head as I grappled with other elements of the film. But Ben! I know you have more to say.Ben: The first thing I thought about was the opening scene of Get Out, which features that super-creepy song Run Rabbit Run as Lakeith Stanfield's character is captured on the street, so this is a fun little callback to the Jordan PeeleVerse.

But more importantly, I think that entire underground compound is a stand-in for the Internet – an entire unseen world just below the surface of our visible one – and the rabbits represent ideas. That long dolly shot over the opening credits reveals that all the rabbits are in individual cages, walled off from one another. But later in the movie, when the cages are opened, the rabbits are let loose, wandering free throughout the hallways, spreading quickly and proliferating uncontrollably. The film opens with a few lines of text about how there's a network of tunnels underground, and late in the movie, we see these tunnels seem to stretch out into infinity, mirroring the infinite vastness of the Internet, with doors lining both sides and rabbits (ideas) hopping in and out of each one. It all struck me as a perfect metaphor for the algorithms of a site like YouTube, where people who are ravenously hungry for ideas (eating rabbits raw) are often led down a "rabbit hole" where they can be radicalized by the fringe views they stumble upon.

At the end of the movie, the Wilson family's son Jason (Evan Alex) has a rabbit in his hands when the family escapes in the paramedic vehicle. What kind of rabbit (idea) did he pick up? Is he infected or enlightened? The answer may lie in his reaction to Adelaide's final realization – but having only seen the movie once, I couldn't quite get a read on what Jason thought about his mother's half-smile as they all drive away at the end.

So, Where Did the Tethered Get Those Matching Red Jumpsuits and Scissors?

Jacob: Part of me just wants to wave this question away and just mumble something about how "Eh, Jordan Peele just thought red jumpsuits and scissors look scary and he's right, it works, so let's move on." But I do think people are going to want to address this, both literally and metaphorically. So let's address it! Maybe we can assume that countless Tethered living in a network of tunnels underground have tracked down enough abandoned janitorial uniforms so they can match? And maybe the scissors are leftovers from whatever experiments were being done decades ago? You've got to use something sharp when dissecting a rabbit.

Still, the bottom line is that the Tethered make for an immediate and terrifying image. The red jumpsuits themselves are a brash statement: they are not here to hide – they are here to be seen. These are not monsters creeping in the dark. These are people who are not going to be quiet about their revolution. As for the scissors, Peele has addressed that choice elsewhere:

"There's a duality to scissors — a whole made up of two parts but also they lie in this territory between the mundane and the absolutely terrifying."

What do you think, Ben?

Ben: If I had to single out one aspect of this movie that will drive people nuts, this would be it. And weirdly, if this were practically any other movie, I'd be asking the same question myself. But Peele is so clearly working on a higher level with this film that I didn't even think about it while watching. He's far more concerned with crafting striking, memorable imagery than answering questions like this. That will infuriate some viewers, and might even be so insurmountable that it will prevent them from fully connecting with the movie. You're right: it feels sort of dismissive to just shrug and recommend that people don't think about this part too hard, but...maybe just try not to think about this part too hard? No satisfying answers lie at the end of that line of questioning.

Hands Across America

Ben: Jacob, I know we've kept the same "call and response" format throughout the entirety of this article, but I want to jump ahead of you in this last section because Hands Across America is the element that most solidified my take on the film. The Tethered (including that one old white guy who explicitly has blood on his hands) are all clad in Republican red, and they join hands to form a literal wall across America. That alone might have been enough to justify my read, but it's the way the movie ends that truly hammers it home: the wall serves no real purpose. Having slaughtered an untold number of people and formed this wall, a long helicopter shot reveals that it's standing firm as the world burns around it. It's completely ineffectual. But I know you have a different take on this aspect of the movie, and I think Peele has said something that backs up your interpretation?Jacob: First of all, your read on this ending chills me to the bone and I love how completely and totally valid it is despite being very different from my own. I'm just picturing Jordan Peele chuckling as everyone draws such different conclusions from his work.

In it's opening moments, Us plants the seeds for the Hands Across America climax with a scene that feels wholly out of place. A young Adelaide (soon to be trapped underground, where she'll become "Red") watches a promo for this famous charity benefit, which was held on May 26, 1986. As the video reveals – filling in the gaps for younger viewers who have never heard of it – Hands Across America would see millions of Americans unite to form a continuous chain across the United States, symbolizing a nation united to work for a better future. It cost $10 to join the line, with proceeds going to fight homelessness and hunger.

Of course, Hands Across America didn't defeat homeless and hunger. It was a loud, flashy stunt that made people with ten bucks and a few hours to kill feel good about themselves. And when it was all over, more than half of the $34 million raised had to be spent on operating costs. It was a grand gesture that actually meant nothing. It didn't move the needle. It didn't fix what was broken.

In an interview with Ebony, Peele addressed this directly:

"Hands Across America was a demonstration that holds the duality of America in it perfectly symbolically for me. This hope – if we hold our hands, we'll cure homelessness, we'll cure hunger – it was well-intended, but was that a solution, or was that a way of not actually dealing with it?"

Still, it's easy to imagine a young "Red" seeing this image, this concept, and believing in it. Believing that if we're loud enough, bold enough, flashy enough, we can make change happen. All it takes is enough people united for a cause. And so, the Tethered rise and they kill those who they see as their oppressors and they unite in a grotesque parody of Hands Across America. Already a naive symbol of hope, this version twists the knife deeper. It's still little more than a gesture – what do the Tethered do now? A bold stunt, whether it's for charity or the climax of a killing spree, is still just a stunt.

Hands Across America didn't fix anything. It became a footnote, a piece of '80s trivia more famous for its cheesy theme song than the money it raised. It's a defunct, broken dream: we stand together and we'll achieve great things. But the Tethered have only achieved death and destruction. And once that chain comes apart, the problems plaguing us will remain...and they'll only get worse.