Wrestling With Martin Scorsese's 'The Last Temptation Of Christ' As It Turns 30

Released this week in August 1988, Martin Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ is, by its very design, a challenging work of art. It's a film that engendered considerable controversy three decades ago and even now when people talk about it, there's a tendency to apply conventional Western thinking and set up a false — or at least greatly oversimplified — dichotomy between the film's detractors and its supporters.

It doesn't really give a full or fair picture to have someone who self-identifies as non-religious defend the film as a grand artistic achievement while summing up the controversy with fiery old stories of picket lines that formed outside movie theaters and death threats Scorsese received. What gets dismissed there is the whole spectrum of moderate responses from a wide contingent of people who wouldn't necessarily fall into one of two camps whereby you either love the film as a passionate cinephile or hate it as an overzealous fundamentalist.

Like Scorsese's other, more recent religious film, the quietly devastating Silence, The Last Temptation of Christ is a movie that stirs profound ambivalence (going by the Google definition of "ambivalence" as "the state of having mixed feelings or contradictory ideas about something.") Over the years, my struggle with the film has been one of biblical proportions, like the Old Testament figure of Jacob wrestling the angel.

A Dream of Domesticity

If you haven't seen the movie and aren't aware of what happens in it or why exactly it was so controversial beyond the obvious spoiler that, well, Jesus dies, maybe now's a good time to go watch it and let it hit you with the full impact that it had on people back in 1988. Then come back here and let's sort through the ensuing aesthetic and/or spiritual confusion together.

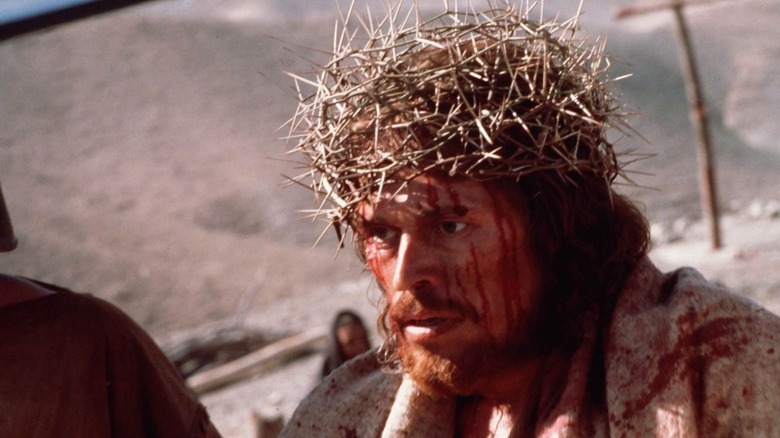

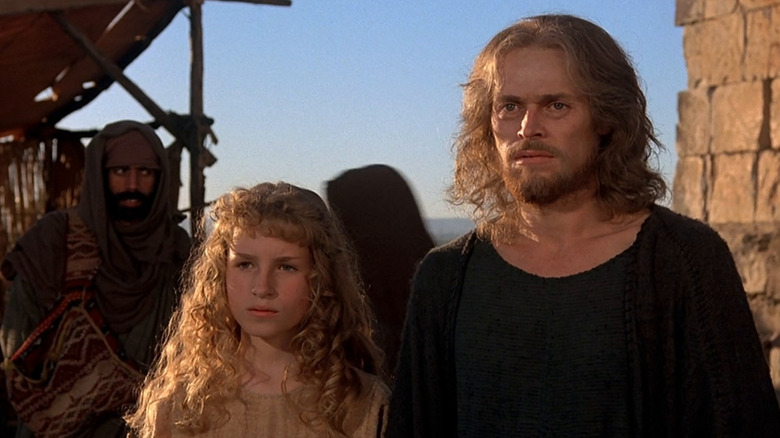

Suffice to say, The Last Temptation of Christ is a movie where Jesus says, "I have Lucifer inside of me," but also, "I'm God!" I'd have to go back and watch Willem Dafoe's eyes closely to see if he actually does it without batting the proverbial eyelid, but you get the point. It's a movie where Christ comes down from the cross and we see him living out a mortal life full of earthly pleasures: making love with his wife Mary Magdalene (played by Barbara Hershey), impregnating her, then taking two more wives and having children with them after she's gone.

This is revealed to be a fantasy sequence — a trick of the Devil, the movie's titular temptation — and The Last Temptation of Christ does include a disclaimer at the beginning that it is "not based on the Gospels, but upon the fictional exploration of the eternal spiritual conflict." However, it's easy to forget that disclaimer when you're a person of the religious persuasion, and you've been swept up in the movie for over two hours, and now, suddenly, the last 35 minutes present this new, extremely unorthodox imagery.

The love-making scene between Jesus and Mary Magdalene is a dream of domesticity, one where Magdalene's excited whisper, "We can have a child," is retroactively tempered by the knowledge that this can never be. It adds poignancy to the sacrifice on the cross because now we see what the human side of this fictionalized version of Jesus gave up. Maybe Scorsese underestimated the power of that imagery, or maybe he understood fully the provocative nature of it and that was what drew him to the project in the first place. Whatever the case, it's a lot to digest.

This wouldn't be the only case where Scorsese flipped the script on the conventional Christian narrative. What makes The Last Temptation of Christ so tricky and troubling for some believers, perhaps, is that it borrows things from the Gospels, but then its "fictional exploration" takes the form of a vivid inversion of the Gospels. Everything is upside down, like the cross used to crucify Saint Peter.

Judas and Jesus

Take Judas, for instance, who is rather opaque in his Biblical portrayal beyond being "the betrayer" who commits suicide (in two different ways; the Bible's inconsistent like that). In the film, Harvey Keitel's Judas is the best disciple, the one who is good, faithful, and strong.

Before 1988, there were other Judas-friendly films about Jesus, like the 1973 rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar (which is celebrating its 45th anniversary this week). That film sought to explore, in song, the character of Judas and add some dimension to him — making him more sympathetic and deepening his relationship with Jesus so that there was more pathos behind that notorious betrayal for 30 pieces of silver. Yet The Last Temptation of Christ takes this Judas revisionism to another level in that it makes Jesus seem utterly passive, at times self-loathing, even feeble, and reliant on Judas for strength.

He's a man filled with crippling doubts. Seeing Jesus build crosses for the Romans prior to his ministry is definitely a new twist on the accepted image of him as a carpenter. At one point in the movie, Judas actually shouts, "Traitor!" at Jesus. It's as if we're watching a stage production of Shakespeare's Othello where the scheming betrayer Iago has now become the virtuous hero.

In the 21st century, framing a story around the villain, making him or her the protagonist and the traditional hero the antagonist, is ground well-trod on television and in movies. That's not exactly what's going on here, but it's a similar role reversal and I don't know that one like it had ever been done to such highly visible effect with a pair of religious icons before The Last Temptation of Christ.

In Silence, Scorsese would toy with the Jesus and Judas dynamic again, only this time, both figures would be embodied as dual aspects of the same character: the Jesuit missionary Rodriguez, played by Andrew Garfield.

The Apostle Paul

Another Biblical character that the film radically reimagines is the Apostle Paul, who was recently played by James Faulkner (alongside Jim Caviezel as Saint Luke) in the faith-based movie Paul, Apostle of Christ. Paul's conversion tale, as told by the New Testament, is widely known through literary osmosis even by those who never attended Sunday school. Under the name of Saul, he started out persecuting Christians, only to be blinded on the road to Damascus and later have the scales fall from his eyes, at which point he was baptized and took the name of Paul as a sign that he had been reborn into Christ.

Almost half the books in the New Testament are attributed to Paul. His epistles, or letters, helped form the backbone of early Christianity and the Church as we know it today, so in some ways, he's a figure whose importance to the Church is second only to that of Jesus himself.

The movie shows us a Paul, played by Harry Dean Stanton, who is a murderous opportunist. He's the zealot who slips a knife into the gut of the resurrected Lazarus. It's a moment that seems tailor-made to foster audience resentment for this character, who undoes the beauty of a divine miracle. At this point, viewers invested in the story are leaning forward in their seats, inwardly hissing at Paul's villainy, thinking, "No! You killed Lazarus! Who does that?!"

When Jesus, now an aging father with grey hair, later runs across Paul preaching in public and he angrily confronts Paul about the lie he is selling — namely, that of a virgin-born Jesus who conquered death — the blustery, disingenuous Paul stops bloviating just long enough to take Jesus aside and say:

"Look around you. Look at all these people. Look at their faces. Do you see how unhappy they are? Do you see how much they're suffering? Their only hope is the resurrected Jesus. I don't care whether you're Jesus or not. The resurrected Jesus will save the world and that's what matters. I created the truth out of what people needed and what they believed. If I have to crucify you to save the world, then I'll crucify you, and if I have to resurrect you, then I'll do that, too, whether you like it or not."

Fantasy sequence or not, this whole speech, which Stanton delivers with wide-eyed, absurdist conviction, offers a pretty dim view of religion, one that seems to say it is indeed no more than an opiate for the deluded masses who need some sort of false hope to get through their otherwise miserable lives. What's more, this message is delivered using co-opted characters, icons from the very religion it seems to be criticizing.

If it's just part of the temptation Jesus' subconscious is indulging in, then perhaps the speech can be viewed on one level as Jesus realizing internally that his life would become a lie unless he actually followed through with his divine mission and died on the cross. The average viewer, however, isn't going to have an appreciation for that kind of nuance. Is it any wonder some people were upset?

Personal and Messy

The great take-it-or-leave-it concept at the heart of The Last Temptation of Christ is that it's essentially an artist superimposing his own spiritual struggles over the life of Jesus. In everyday life, of course, people project their own attributes onto their vision of God all the time. God becomes made in their own image, as opposed to the other way around. At the end of the day, all any us can ever claim to really know about God is the conception we carry. We conceive of a higher power this way or that or maybe we conceive of a universe with no God at all.

They're all just human conceptions. Even people who look to the Bible and try to use it as the basis for their conceptions are liable to take certain verses or chapters out of context and maybe come away with horrible misconceptions that are not scripturally sound. This summer, references to Romans 13 suddenly popped up in the news, as its citation by a politician caused journalists online to unpack the dark history of that particular Bible chapter being used to justify slavery.

In high school, while I was still reeling from the head trip of seeing The Last Temptation of Christ for the first time, it prompted me to check out Scorsese biographies from the local library, since this was just before the rise of the Internet when there were only tattered old books to give information. If you've watched The Wolf of Wall Street, then you wouldn't need to read a Scorsese biography or even just a revealing interview to guess that he was no saint. A self-described "lapsed Catholic," he's a man who once struggled with a serious cocaine addiction and has been married five times. Many of his films seem to willfully embody the sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll lifestyle and if there's a moral in there, you'll need to wade through some wickedness to get it.

"It's a funny feeling being taken under the wing of a dragon," says Leonardo DiCaprio as Amsterdam Vallon in Gangs of New York. Scorsese's films are full of dragons in human form, like the one with the devilish grin played by Jack Nicholson in The Departed, who even quotes Lucifer's own Latin via James Joyce, saying, "Non serviam." I will not serve.

Growing up in the rough neighborhood of Little Italy in Manhattan's Bowery district circa the 1950s, Scorsese seems to have gravitated toward the philosophy that he himself narrated in voice-over at the beginning of Mean Streets: "You don't make up for your sins in church. You do it in the streets. You do it at home. The rest is bullsh*t and you know it." His films often showcase the worst aspects of a fallen humanity.

This has resulted in the proliferation of the priestly quote, "too much Good Friday, not enough Easter Sunday," in reference to Scorsese's work. It's a quote that grew out of an old remark made by Scorsese's own parish priest. Understanding that — knowing his foundation of Catholic guilt — when you sit down to watch The Last Temptation of Christ makes it easier to come to terms with the film as a cinematic prayer, one where the sinner, misguided or not, takes comfort in imagining that his savior was maybe not so different from him.

It's a messy process, this act of unfolding an imperfect prayer on celluloid. In a lot of ways, Scorsese's most personal film is also his untidiest, both in terms of its theology and in terms of its production. To get it made, Scorsese agreed to do it in 58 days for half the original budget, with little rehearsal and scenes being improvised. In an interview this year, Dafoe said they were doing two or three takes for scenes—a far cry from the stories of Scorsese doing a hundred takes for scenes in New York, New York.

Maybe that's why the acting is so bizarre in The Last Temptation of Christ. You've got characters in robes and sandals using the modern vernacular and speaking with Brooklyn accents and it takes a while to surrender oneself to that interpretation and get past the point where the whole thing feels like a heaving melodrama with community actors. Influenced by world music, there's no denying the power of Peter Gabriel's soundtrack, however, and 30 years later, the film's striking images — like the one where Jesus reenacts Roman Catholic iconography by pulling his own heart out of his chest — remain undiluted in their potency.

Churchgoer, Moviegoer

For some, the very idea of rewriting the Bible, turning the "greatest story ever told" on its head, dooms this movie from the start as a hubristic, sacrilegious endeavor. Some of the film's most vocal detractors — possibly that fellow holding a "God damns blasphemy" sign outside the theater in 1988 — are people who have never even seen the film and in fact, vowed never to watch it on principle. They have base-level objections to the movie because unlike the Gospels, it balances itself rather unsteadily on the idea of Jesus as a flawed messiah who is subject to the same lusts and human weaknesses as the rest of us.

Whether that's an ill-conceived idea or not, it definitely pushes some buttons, and for believers, it surely doesn't help the movie's cause that it seemingly delegitimizes things they regard as holy like the aforementioned virgin birth and resurrection and Saint Paul. Belief is a lens but it also might be called a prism (or prison) through which an individual sees the world.

I can sympathize with that a great deal. Where I'm coming from is the perspective of a moviegoer who also happens to be a churchgoer. Since gaining exposure as a teenager to his legendary collaborations with Robert De Niro, I've been mentally wrapped in the robe of a Scorsese acolyte. However, I also put on a real robe and served as an altar boy alongside legit church acolytes on Sunday mornings.

There's undoubtedly a paradox at play in serving two masters like that. Movies like Goodfellas and Casino, which my church youth group friends and I quoted endlessly in our best De Niro accents, still rank high on the list of films that most frequently use the f-word.

Watching Goodfellas one night, I remember my conservative Christian father walking in the living room as my mother and I were right in the middle of the famous "Funny how?" scene, where Joe Pesci is dropping f-bombs left and right. My father was disgusted with all this cussing garbage. He wasn't in the mood to hear such filth in his own home. Scorsese's parents were apparently no different: addressing the vulgarities in Mean Streets, his mother once said, "I just want you to know one thing, we never use that word in the house." But at any rate, my father made us turn off the movie that night. It's one of the greatest motion pictures of the 20th century...but I had to wait until later, after my parents had gone to bed, before I could sneak back out to the living room and finish watching Goodfellas.

Tailored Christ Narratives

Despite the incongruence of experiences like these with the way I was raised, I never let go of the faith my parents had instilled in me. Call it brainwashing, if you want. They even programmed me with a name, Joshua, derived from the same Hebrew name as Jesus. If you've seen The Passion of the Christ, where Jesus is notably referred to as "Yeshua," then you've heard that Hebrew name. As mentioned in my article earlier this year about four of the best religious films, my own religious background led me to a pre-seminary stint in New York similar to the one Scorsese had before he became a movie director.

Studying the literature and history of the New Testament at a private Lutheran college in Bronxville, I learned that what the Gospels presented was not differing eyewitness testimony but rather a transcription of oral accounts where the writers each had a different audience in mind. They took license with the story and maybe changed certain details to fit their audience better. This explains some of the contradictions in the Gospels, why the genealogy of Jesus, for instance, doesn't match up between the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke (the former being written to a Jewish audience and the latter being written to a Roman audience).

In the oral tradition, it was the moral of the story that was important, not the minutia of every last little thing that happened. If this sounds like a devil's-advocate argument on behalf of Scorsese's right to reinterpret the story of Jesus for a secular audience, it's not that, per se. It's just to say that there are aspects to the Bible that are undeniably literary rather than historical and should be considered as such. A more straightforward adaptation of the Gospels brings with it its own questions, like which version of events in which Gospel should be given preference.

The screenplay for The Last Temptation of Christ was written by Paul Schrader, a frequent Scorsese collaborator who came from a strict Calvinist background and minored in theology at a Christian Reformed Church college before earning his master's degree in film studies at the UCLA film school. Like Scorsese, Schrader's filmography juxtaposes religious concerns with sex and violence, stringing up the sacred and the profane in an apparent web of worldly contradictions. His most recent film, First Reformed, which is also his best-reviewed directorial effort, stars Ethan Hawke as a Protestant minister undergoing a crisis of faith.

In exploring questions of faith on screen, did Scorsese and Schrader go too far with The Last Temptation of Christ? To this day, it's the kind of movie where you don't have to look hard to find YouTube commenters describing it as "diabolical." Elsewhere online, the bad blood engendered by this film still manifests itself in polemical blog posts. A former nun turned PhD, for example, who served as a theological consultant on The Passion of the Christ, paints Scorsese as spiritually immature, "a lifelong flailing apostate," who was equally unfit to adapt a complex Catholic novel like Shusaku Endo's Silence.

To be honest, if you scrutinize some of the things Scorsese and his religious critics have put out into the world, administering the test of that old line of scripture, "You will know them by their fruits," both sides come out looking bad, as if neither one of them had any business commandeering Christ in the first place. No one stands unimpeachable at the judgment seat. Such is the world we live in.

Jesus Fandom

It sounds ridiculous, but from an objective standpoint, what a lot of the flak for this movie boils down to is that Jesus has a significant fan following, like Batman or Star Wars, only much more intense since he's regarded by 33% of the world's population as the Son of God and his fandom, as it were, is tied to bracingly real life-or-death matters. The Last Temptation of Christ is a movie that was clearly made in earnest, but if you're a Jesus fan, you might see it as a film helmed by the wrong guy whose take on the material leads the 2,000-year-old franchise of the Christian religion astray. The parallels between this movie and The Last Jedi are something Bryan Young delved into just last month in a feature for /Film.

Scorsese's film is problematic; it poses questions without pat answers. Is it even great art, top-tier Scorsese, or do the issues that plagued the production spill over into the film frame? What does it mean to be a Christian or any kind of person who feels a higher calling in life? What is it like to resist, then respond, letting that "still small voice" that is speaking to you out of the innermost recesses of your own mind finally take control of your actions, dictating your destiny?

If you strip away all the religious trappings, The Last Temptation of Christ is, at its heart, a movie about staying true to your purpose. At one time, Scorsese thought his purpose was to be a priest. Maybe he was still wrestling with guilt for denying that calling, or maybe he had simply found a new vocation to be a filmmaker.

As for the controversy and whether or not it's deserved, if you're not religious — if you don't have a dog in that fight, as Mel Gibson once infamously put it — then think of it this way. Imagine your absolute favorite book was getting made into a movie. Now imagine there was a different, non-canonical version of the events from that book floating around out there in the form of a fan fiction story. Rather than adapt the book itself (in this case, the Bible), the director of the movie decides to adapt the fan fiction story (in this case, the novel by Greek author Nikos Kazantzakis). Obviously, there are going to be some fundamental differences between the text you hold sacred and the big-screen adaptation — which is, after all, an adaptation of a different story featuring the same characters.

In theater, there's this idea of the worshipful versus the heretical approach to a stage play. Those terms are borrowed from religion, which makes it potentially confusing to apply them to a religious film; but the point is, with the heretical approach, the play is not sacrosanct and the director is free to offer up his or her own new dynamic interpretation of the material. An example of this in cinema might be Baz Luhrmann's interpretation of Romeo and Juliet, which rejiggered Shakespeare's play as a modern-day gangland story where the Montagues and the Capulets were feuding crime families in a place called Verona Beach.

It is Finished

The Last Temptation of Christ is a heretical take on the life of Jesus. Some religious viewers might regard the movie as literal heresy. Unfortunately, I dropped out of my pre-seminary program, so I don't have a clerical collar to lend authority to my film analysis. I'm nothing more than a layman, like Scorsese himself professes to be. All I can say is, in endeavoring to be open-minded while also attempting to reconcile the movie with what the churchgoer in me believes, I've always referred back to that disclaimer, the one I quoted before, warning that the film is "not based on the Gospels, but upon the fictional exploration of the eternal spiritual conflict."

In some ways, Scorsese's film still seems cleaved to a limited perspective, unable to conceive of a resurrected life where the spirit and the flesh are not diametrically opposed forces vying for the soul of the believer. Steeped in dualism, this Gnostic worldview is hammered home everywhere from the film's epigraph, where it talks about the "battle between the spirit and the flesh," to Dafoe's prayer as Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane, where he says, "Father in heaven. Father on earth. The world that you've created, that we can see, is beautiful. But the world that you've created, that we can't see, is beautiful, too."

As a Christian, my knee-jerk reaction to the film on a recent rewatch, after not having seen it for some years, was that it got the character of Christ completely wrong, turning him into a cockeyed lunatic. The suffering servant was there, maybe, but the confident king — that regal presence who spoke authoritatively — was nowhere to be found on screen. When Dafoe's oddball Jesus finally gets over his self-doubt and rises above the crowd in the temple, galvanizing his followers, ready to embrace the way of the ax, vociferating about setting fire to the world, the level of histrionics makes him seem like a man who is dangerously unhinged.

It is possible, however, to hold a mixture of feelings about this film, simultaneously recognizing its artistic merits and recognizing where Dafoe's Jesus might be more relatable to some people, insofar as it's a little hard to build your narrative around a protagonist who's without peer as God's only begotten Son. Maybe the only way to do a really compelling, faithful film adaptation of the Gospels in post-modern times would be to make it a perspectivist story told through the eyes of Jesus' disciples.

In the end, I can relate to The Last Temptation of Christ on the level that I'm human and hypocritical and I've certainly found that my own desires are in outrageous conflict sometimes, much like those of Scorsese's atypical Christ. If what Scorsese set out to do is make a movie that would speak to people who have walked the line in their lives between opposing hemispheres of human experience, warring selves, contradictory actions and beliefs, then the film succeeds resoundingly in that aim.

If I live another 30 years and grow a grey beard like Old Man Jesus, maybe I'll outgrow this film and be able to dismiss it...or maybe I'll still be contending with The Last Temptation of Christ. Like many artists, Scorsese seems most comfortable operating in the ambivalent realm, the grey zone rife with paradoxes and penumbras. As viewers, maybe that's right where he wants us, too.