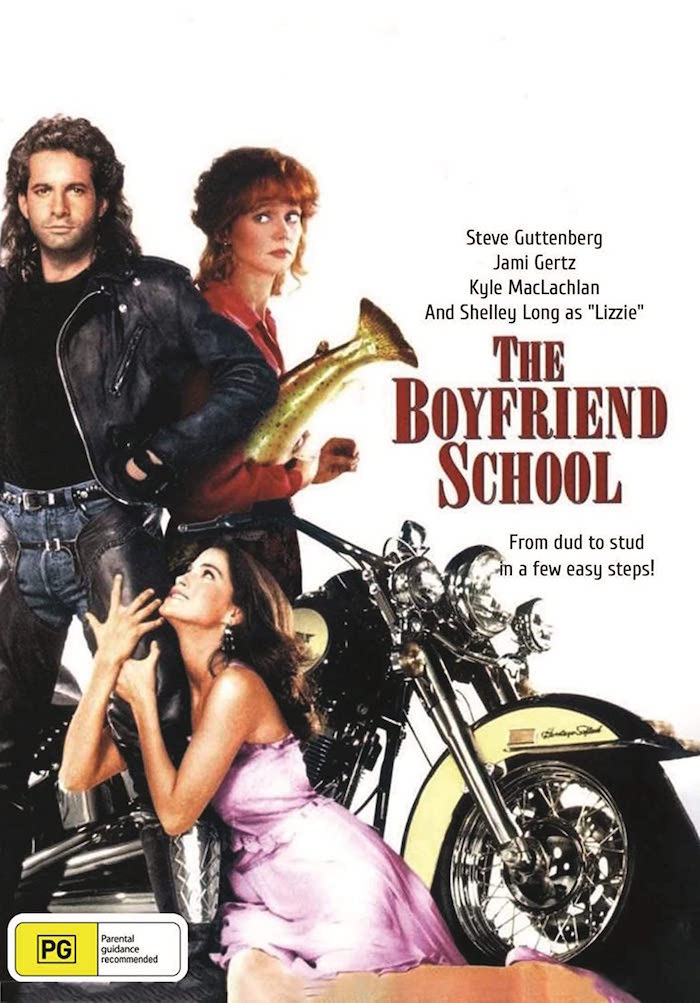

How Did This Get Made: A Conversation With The Producer And Editor Of 'The Boyfriend School'

This week, the gang at How Did This Get Made? covered The Boyfriend School, a 1990 romantic comedy starring Steve Guttenberg, Shelley Long and Jami Gertz.To better understand how (and why) this film got made, I spoke with the film's editor, Marshall Harvey, and its producer, George Braunstein. Given that George Braunstein hasn't produced a film in several years, and that he's best known in Hollywood as an entertainment attorney (he's a partner at Braunstein & Braunstein), I was particularly curious to hear how he had gotten into producing films. And the answer to that question begins in the late 1940's... The interview below has been lightly edited for clarity.

Part 1: “You Don’t Learn from Success, Brother”

GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Initially, my father (who's unfortunately not alive now) was an attorney and a CPA in New York. And he had been approached by some people that—right after the war—wanted to do a movie with Polly Bergen, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis called At War with the Army. The film was going to be black and white and relatively inexpensive. So my dad put up the money for the movie. And, you know, because no one can second guess show business, right? It was a hit. At War with the Army—a musical comedy with the tagline "America's Funniest Guys are GI's!"—was released by Paramount in December 1950. The film was a success—becoming the eighth highest-grossing film in the US (and finishing as Paramount's most successful film in 1950). GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: I was a little boy then, I was just five years old. But I remember meeting with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, and going on set. And just early on in my life—because of my dad—I kind of got interested. And then my father had... so growing up, a very good personal friend of my dad was an agent (whose unfortunately not with us) by the name of Irving Lazar— [who went by the nickname] "Swifty" Lazar. And so my dad told Swifty that he had optioned this book, The Young Lions. The Young Lions is a novel by Irwin Shaw—set during World War II—that was published by Random House in 1948. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: And the way it was done back then... [restarting] Swifty was on a flight—either to New York or from New York—with some executive at Fox. He said, "Hey, how about The Young Lions by Irwin Shaw?" And on that transatlantic flight he set it up.The Young Lions—starring Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift and Dean Martin—was released by 20th Century Fox in April 1958. The film was a success—finishing the year as the ninth highest-grossing film in the US.GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: And then Swifty [Lazar] introduced my dad to a screenwriter named Ben Hecht. And Ben Hecht was kind of at the end of his life, more or less. But he still was a powerful writer...and there was a book out—this was prior to The Godfather—called Brotherhood of Evil that was a bestseller. It was a "tell all" book about organized crime in America. So my dad optioned that, took it to Ben Hecht. And then Ben Hecht wrote a screenplay. That film, however, was never made. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Unfortunately Ben Hecht died, then my dad died. I still have the script. It's one of those projects that you say you're gonna do one day...Braunstein isn't being flippant here—he's been passionate about getting it made for several decades now. Per a Los Angeles Times article from 1987: "[a] script about the drug world from legendary screenscribe Ben Hecht—willed to an 11-year-old—may find the light of the silver screen as a contemporary drama. 'Brotherhood of Evil,' perhaps the last unproduced Hecht screenplay, was willed to producer George Braunstein by his late lawyer dad, who got it as payment for packaging the 1952 Dean Martin-Jerry Lewis comedy 'At War With the Army.' GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Meanwhile, I went to high school; went to college; and when I went to UCLA, I thought about taking film, or theatre arts courses, but I got a degree in biology and biochemistry. I don't want to date myself, but I have no choice. I graduated UCLA in 1969, so it's the height of the opposition to the war in Vietnam; the music revolution; it's hard to even describe what a different time it was. So here I was...I was a nerd walking around with a slide-rule in my pocket—a math and science major. BJH: So on your graduation day...what did you think you were going to [do as a career]?GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Well that's just it. So graduation day, a friend of mine says: hey, George, why don't we go down to this night club [in South Central]? I grew up in West LA. I'd never hung out in South Central LA in my entire life. Never. I hate to sound like an asshole but...I lived a block away from UCLA. And that was my orbit, more or less. I said, "Hey, why not? Let's do something crazy." So I went down to this night club called "The Apartment" on Crenshaw. And I was the only white person in the club. And there was a band that had just come in from Kansas City. The band was a doo-wop group called The Sinceres. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: You're not gonna believe this story...so they were singing, you know, Temptation songs; Smoky Robinson songs. But what I noticed was they were self-contained. In other words: they didn't need a band. They had a lead guitar, a bass guitar, a drum, an organ and percussion. So they were like a rock n' roll...they were like a rock n' roll band, but that sang rhythm and blues. And [after they finished their set] my friend took me backstage to meet the band. You guys are great! I wanna buy your album! And whatever we were saying back in the 60s: far out! BJH: [laughs]GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: And they said, "We're here from Kansas City, we're trying to get a label." Now, at that time, I knew nothing about music. Nothing about anything. But I thought to myself: wow, wouldn't it be cool to be in the music business and, like, "join the circus" for a year and then go to medical school. So I say [to the band], "Hey, that sounds great! I'll help you do it!" I mean, it was just like the influence of having a beer (because I didn't really drink) and then this romantic idea of getting involved with this rhythm and blues band. BJH: How did your family feel about this bold move? GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Yeah. So I go home. By this point, my dad had died. I tell my mom: hey mom, I'm gonna take a year off [to help out this band]. She tells me, "you can't do that, you're nuts." Verboten. BJH: Ha! So what did you do next? GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: [At that time] English rock was so popular. With The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. And I had spent two summers in England. UCLA had a student travel program [in conjunction with] an airline called "Dan Air." [laughing at the memory of "Dan Air."] So Dan Air was, like, they would get recycled jets with everything falling off...BJH: [laughs] Did you know anyone in England? Anyone who could help with this new career? GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: We had a family friend who happened to represent The Beatles...this friend was a lawyer—his name was Bruce Grakal—and Bruce says: don't do it! Go to medical school. It's too difficult! 10 records come out a week, you'll never get airplay! He told me all the reasons why it was impossible. But the more the people told me "impossible," the more I thought: I can do that! BJH: I like that. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: So we buy the Dan Air tickets...I tell [UCLA] that the band is studying "ethnomusicology" and we get the cheap ass tickets to London. BJH: [laughing]GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: And these guys, you know, believed in me. I don't know why. They were all grown adults. They should have looked at me and said, "Who's this freak?!" But I had a lot of enthusiasm. And the band was good. They were a good band...BJH: You said they were called "The Sinceres," right? GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Yeah. But [after becoming their manager] I said, "You can't be the Sinceres!" So we came up with the new name: Bloodstone. BJH: Gotcha...GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: So we go to London. I start scrounging around. I find an agent who doesn't care that we're illegal aliens there [in the UK without the proper work permits needed at that time] and he gets us on the Curtis Mayfield. And at that time in England, The New Musical Express was a big deal. And they had a stringer [at the Curtis Mayfield concert] to cover the show. We open the act. We had 10 minutes...singing songs like "I'm so Happy I'm Black" and the next day we're on the front page of The New Musical Express. BJH: That's wonderful! GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: And then the agent who booked us...he said, "Hey, man, the record companies are calling." Now remember: I don't know anything. I've got Bruce Gakell here in LA giving me advice over the phone. So I go to Decca; to EMI; to Island, to Polydor—all the big record companies...and I just went 'til the bidding stops. Decca gives us a big recording contract and then we stayed in London and made records. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: The first two records were flops, but the third one we released was a #1 international hit. Worldwide hit. Called Natural High...BJH: Wow. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: [Nevertheless] it was so difficult. We had been on tour with Al Green. We had been on tour with Elton John. We had been on tour in Europe. And to go on tour as a rhythm and blues band is very, very difficult. I mean it's really hard work. Every day's a different gig; you're flying, you're traveling. BJH: Sure. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: So I went to see [the head of Decca Records] Sir Edward [Lewis], who liked me. I think I went in with a Gold LeMay Suit with, like, 6-inch platforms. BJH: [laughs]GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: And because I was making a lot of money for him. I said, "The Beatles are doing movies. The Monkeys are doing movies...give me the money to do a movie. And he writes me a check. And I come back here to LA and I have a budget for a movie for this group Bloodstone. BJH: That's wild. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Now at that time, there was a screenwriter who was my dear friend. He was dating my niece. And we graduated UCLA together. His name was "Dan Gordon." I don't know if you're familiar with his credits but he [later went on to write] The Hurricane, Murder in the First, Wyatt Earp. BJH: Oh, I definitely know Dan. I did a long interview with him a couple years ago. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: So then I tell Dan the story I just told you...and he says, "Hey man, I'm your guy! I'll write the movie for you!" So, yeah, Dan writes me a script. He calls it Night Train. We ultimately called it Train Ride to Hollywood. And then Dan goes to Israel and gets drafted.BJH: I remember!GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Now, [at this point] I know less about the movie business than the music business. Because in the music business I'd had some disappointments. Which I learned from. And you don't learn from success, brother, you just learn from when you screw up! BJH: [laughs]GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: So I knew more about the record business. And now I'm interviewing directors and I'm going to studios and I'm thinking about my dad who's not alive. Braunstein ended up hiring the director Charles Rondeau.GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Charlie had done [episodes of] F-Troop and Love, American Style. And Charlie says the script is shit. We need to bring in a new writer. So I call Dan in Israel and he's on active duty in the Golan Heights. BJH: [laughs] Wow. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: He's a Corporal in the Golan Heights and they're fucking shooting at him! I said, "What do I do, man?" He says, "Bring me back there." I said, "Okay, well how do we do that." I forget exactly what I did, but eventually I found someone who knew someone who knew someone and...Dan Gordon's Commanding Officer pulls him out of combat and says, "You're needed in Los Angeles to go work on the movie on Night Train."BJH: Ha! That's amazing. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: So Dan comes back. He gets off the plane in his fatigues. A car backfires at the airport and Dan, like, hits the ground. Like someone was shooting at him. He was still in a total state of alarm. So Dan comes and rewrites the script. We reach a happy medium with Charlie Rondeau's writer. We get the movie done and [famous] people were looking at and liking the movie. Groucho Marx asked for a screening. Mel Brooks. But I didn't know how to capitalize on it. I didn't know anything at that point.BJH: Still, that's really impressive. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: So that was how I first got into making movies. Then I had the bug and I just wanted to make more movies. After Train Ride to Hollywood, Braunstein would next produce Fade to Black (1980) and Surf II (1984); then five years after that would end up producing a film called The Boyfriend School.

Part 2: And It Went Downhill from There!

In 1989, editor Marshall Harvey was flying high. He had just finished cutting the Tom Hanks comedy The 'Burbs and—with that film now in the can—he began looking for his next project... MARSHALL HARVEY: My agent set me up on an interview with Malcolm Mowbray, the director. I had seen a film he did in England called A Private Function that starred Michael Palin from Monty Python and I really liked it. So I was excited to meet him. And we hit it off right away. Especially when he found out my film teacher in college was Alexander Mackendrick, who had done a lot of classic British comedies in the 50s (with Peter Sellers and Alec Guinness). Those were films that Malcolm had grown up with...BJH: Right. What kind of stuff do you remember him saying about The Boyfriend School? Like: why was he excited to do it? How was he sort of pitching it to you? MARSHALL HARVEY: Who? Malcolm?BJH: Yeah. MARSHALL HARVEY: I think he had a two or three picture deal with Hemdale Corporation. He had done a movie before called Out Cold—a black comedy with Jon Lithgow and Randy Quaid....I think he just loved kind of quirky, dark comedies; as do I. And so, you know, it was a gig. [laughs] He was trying to get a foothold in America as a director. But unfortunately, the first movie, Out Cold, made no money whatsoever. Hemdale, at that point in the late 80s—this is John Daly's company: Hemdale Corporation—they were riding high on co-producing the first Terminator movie and winning the Oscar for Platoon. So they—like some other companies in the late 80s decided: well, we'll distribute the movies we make. But, you know, the distribution is so much different than making movies. And like De Laurentiis had "DEG" in the 80s, that went belly-up and so did Hemdale; not long after Boyfriend School came out.BJH: Ah, okay. That makes sense. MARSHALL HARVEY: Anyway, [Malcolm and I] we hit it off right away. So I got hired. We went to Charleston, South Carolina, which was beautiful. I enjoyed that. And it went downhill from there! BJH: [laughs] What do you remember about the title change...? Harvey excitedly pulls out an old newspaper ad for The Boyfriend School—mentioning that when he was hired and all throughout production the film had been called Don't Tell Her It's Me. MARSHALL HARVEY: But by the time the film was finished, I guess they had a test screening and people didn't "cotton to" the title so much. I was long gone by then. And only found out about the title change when it was released in theaters. And I just thought: this is a terrible title. It just reeks of desperation, ya know? It's one of those forgettable titles that...I never liked it. Harvey was not alone in feeling this way. In fact, the opening line of Variety's review of the film says exactly that (and worse): "Don't Tell Her It's Me starts with an awkward, impossible-to-remember title and goes downhill from there. This grotesquely unfunny comedy, with Shelley Long as a romance novelist transforming shy brother Steve Guttenberg into a swaggering stud, should escape quickly from theaters."MARSHALL HARVEY: Yeah, it got bad reviews. It made no money. Partly because Hemdale didn't have enough clout, or money, to really advertise enough. Or book the theaters. That was the trouble with a lot of these small companies making smaller movies. You know, a major studio can say to a theater chain: well, you want our next Back to the Future movie? Then you gotta book Don't Tell Her It's Me or yada yada yada. But a company like Hemdale: they have no clout. So it's like: please take our movie!BJH: What do you remember from the editing of the film? Any particular challenges stand out? MARSHALL HARVEY: It was a long time ago. We were still cutting on film. I was on location for the 6 [or] 7 weeks, whatever. Malcolm and I got along really well. There were really no problems until later in post-production over the final cut and whatnot. BJH: Gotcha. MARSHALL HARVEY: I don't remember cutting too much out. But watching it last night I do recall there were at least a couple of short scenes with Kyle MacLachlan and Mädchen Amick that got deleted. And I think that set up kind of a subplot that MacLachlan was two-timing Jami Gertz and Mädchen had a rich father who was gonna put money into his business. Or something like that. There were a couple of scenes. And those got tossed. Probably for pacing reasons. And also in the last scene where we see them in the movie their dialogue kind of explains all that. But other than that I don't recall any real problems. Sometimes a lack of coverage. Mostly with the little girl. But she actually came across really well. BJH: One final question: When was the last time you saw the movie? MARSHALL HARVEY: [excitedly] Oh! I did listen to the podcast. And I was pleasantly surprised by how much they liked it, actually! Mostly for the cast (which was great). I hadn't seen it in 30 years. But I did find a VHS copy and watched it last night to refresh my memory. Because they talked about a lot of things that I completely forgot about. BJH: What did you feel watching it last night? MARSHALL HARVEY: That it has its moments. The running gag with the little girl always worked in screenings. We knew that was gonna work. The scene with Beth Grant as the sex teacher always worked. [But overall] it's just one of those premises that...it's a hard sell. BJH: Right. MARSHALL HARVEY: [after a moment of reflection] I felt bad for Jami Gertz because she has to play it real. But unless she was a complete idiot, how could she not see through this plot? But anyway...but the cast, for the most part, is good. And there's some good moments in it. What happened in post-production, I think, is they said that Malcolm's early movie made no money and the people at Hemdale (John Daly, specifically) really started getting cold feet when we were in post-production. And especially there were a lot of executives meddling—fighting with the director over god-knows-what. Stupid stuff. And most importantly: they kept cutting the post-production budget down. Which may be the reason I don't remember going to the sound mix. I think they let me go early. To save money.

Part 3: Producers and Prize-Fighters

Trying to "save money" is by no means unusual during post-production. Though it's a bit odd to try and find those savings in the editing department. That, however, makes more sense when factoring in the challenges facing John Daly, Derek Gibson and their Hemdale Corporation at this time. But before that, let's go back to 1984—to right after George Braunstein had produced his first three films: Train Ride to Hollywood, Fade to Black and Surf II. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: I'd made three movies and...none of them were big hits. Train Ride got locked up with Billy Jack. Fade to Black, American Cinema bought it and then went out of business. And then Surf II, nobody went to see it. So I thought: I'm never gonna work again. I'm not gonna be able to support my family. So I started to go to law school at night. BJH: Ah, okay. So that's how you ended up becoming a lawyer. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Yeah. So during the day, I'd [continue producing] with my 100% rejection rate. I had a 50-cents-per-square-foot office in a warehouse in Santa Monica. And then at night, I went to law school. So needless to say, I'm not sleeping at night, and the weekends are gone; but I produced three movies while I was in law school. BJH: Wow! The first of the three films that Braunstein produced while in law school was And God Created Woman (1988), directed by Roger Vadim. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: And by this time I have people who know people who were giving me projects. And I had gotten a script called Hamburgers. It was about a butcher who has a relationship with his partner's wife and they...it was a comedy murder mystery. And I give it to this English director Malcolm Mowbray and he says, "Oh, I love it." BJH: What made you think of Malcolm for that movie? GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: I had seen this film I just loved called A Private Function that Malcolm had directed. Braunstein—with Malcolm Mowbray attached to direct—then took the "comedy murder mystery" script to John Daly and Derek Gibson at the Hemdale Corporation. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: They were big fans of Malcolm. BJH: What were they big fans of Malcolm from? From the same film you had seen? GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Yeah, A Private Function. John Daly was English and he was a great...I'll tell you: I did two movies with John Daly. And any day of the week, I would rather do a movie with John Daly and Derek Gibson than do a movie with a studio. Because with all of my studio experiences: I never knew who I was talking to. But when I showed up with John Daly, he wrote the checks. He was in charge. If you could deliver the groceries mono-a-mono with John Daly, you got your way. If you couldn't support what you wanted; if you couldn't support your position, or you lied to him, you were out. But at a studio: everybody's lying!BJH: Ha!GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: So [the script] Hamburgers was turned into...fuck, what's the name of that movie?BJH: Out Cold? GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Out Cold. Thank you. Jesus Christ, Man. I gotta get to the "Memory Center" right away. BJH: [laughs]GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: John wouldn't do the movie until I got some cast. He said, "Look, I like you George. I like the script. I love Malcolm." But he had a deal with Tri-Star and Tri-Star had certain minimum requirements. And so I said: how about John Lithgow? Lithgow, at the time, had just been nominated for his second Tony Award for his performance as "Rene Gallimard" in M. Butterfly. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: CAA represented me, but they wouldn't give the script to John Lithgow. So I get the fucking script to John Lithgow. And I sent him a copy of A Private Function. And he calls the agent up and says, "Why are you keeping the good material from me? I love this!" Then I go to John [Daly], who writes [John Lithgow] a million-dollar check, pay-or-play. So John [Daly] gives me the money for Out Cold. We set up a production office in San Pedro. We do it on location in a butcher shop there. We had John Lithgow; we had Terry Garr; we had Malcolm; we had so much fun doing Out Cold. But then John [Daly] got into a fight with Tri-Star and the picture never got distribution. Unfortunately. It was never released...BJH: Damn...GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: I mean, when the movies get out there and you get in front of a bunch of eyes, you create, kind of, a critical mass that helps you in your career. If you make a movie and nobody sees it, then you're just another dope, you know? Anyway [after Out Cold] Malcolm and I read a book called The Boyfriend School. Written by Sarah Bird. It was a romantic novel and we thought it would be fun so we took it to John [Daly]. John agreed to do it. Again, I had to get cast. He wanted Jami Gertz. And I'd always been a huge fan of Steve Guttenberg. So Guttenberg said yes. Jami said yes. John said yes. And then we went to South Carolina and did the movie. BJH: Was it hard to get Steve? He was so popular at that point in time...GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Well, you know, it's all the material. He and his manager loved the material. They loved the director. And I think he wanted to get out of...he had done multiple versions of Police Academy and then the three-bachelor dad movie [Three Men and a Baby].BJH: Right. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: In other words: they kept him working—getting the paycheck—but not doing anything artistic. And so I came to him with Malcolm and with [a project] that wasn't a "remake" of Police Academy. BJH: [laughs]GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: So I brought him something different and he was a dream to work with. Shelly Long was a dream to work with as well. And she and Steve got along—so we all got along. I remember on the set one day...now, mind you, I'm telling you this from a place of love for John Daly and Derek Gibson. A lot of people have horror stories, but I loved them. Because John Daly was a true grit. He was a hero. So was Derek Gibson. They were great guys. But you had to be. You had to match 'em mano-a-mano. You had to show up and be prepared to take the consequences. BJH: Gotcha...GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: So we're on the set. So now John assigns a studio executive to the set. We're in Charleston, we're on location, we're about a week away from shooting. Great city. I mean, I could talk for hours about Charleston, but I'm just gonna give you the highlights here. And then we're getting ready to shoot the movie—we're a week away—and this guy shows up; he was an accounting major, or some relative of a friend of John's. He says, "Hi, I'm the executive that's assigned. I'm going to be the liaison between you and John. He's doing four other movies, so I'm gonna be here. And report to John." And I sat him down in my office in Charleston. I can remember it as if it was yesterday (though I don't remember his name, of course). And I said, "Listen, pal, I'm going to give you access to everything. You can come to the dallies. You can be on set. You can come to the production meetings. You can be a fly on a wall to everything going on. I want John to know everything that's going on in this movie. There won't be one thing I keep from you. But by god if you turn out to be a rat and you start sending information that is not truthful, or you try to curry favor with John Daly by doing something that will hurt this production, it's over for you. It's your choice. BJH: Okay... GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: I didn't really trust the guy. You know, I made the speech. But you know how you get a feeling sometimes where a guy's just a snake? Like he wouldn't make eye-contact with me. Anyway, so we gave him an office and we gave him a fax machine...and unbeknownst to him I had our tech guys wire the fax machine so that when he sent a fax—no matter where it went to—I got to read it first. And, you know, after the first day of dallies he [faxes John] that "the production's in chaos" "people are running here and there." Because he didn't know! He'd never been on a set before in his whole fucking life. And I see this fucking fax that never got to John Daly and I called him in and said, "Pal, you make the actors nervous." And I'd told everybody; I'd told everybody the story I just told you. And then I said, "You make the actors nervous. You're banned from the set. You can't eat with the cast and crew. You're banned from dailies. Just stay in your fucking hotel room and if something comes up, I'll let John know and then maybe he'll let you know." He says, "You can't do that! I'm the studio executive on this film." I said, "Watch me!" BJH: Ha!GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Then John called me up and says, "George, you're disrespecting me. This is my eyes and ears on the show. You can't do this to him." I said...[this guy] shows up and Steve [Guttenberg] gets nervous. He can't deliver his lines. Shelly Long...she gets a case of the vapors, she can't do anything. I said, "I can slow the production down, but then we're gonna go over budget. If that's what you want, I'll have him sit right there." He says, "Oh, forget it. Forget it." [laughs] BJH: [laughing]GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: But then we made the movie and it just...you know, John was struggling to [keep the company afloat]. He was totally financed by Crédit Lyonnais. And when the banks get ahold of your company...he had this incredible [film] library. He had Platoon, Hoosiers, The Last Emperor. I mean, John was a genius. He'd made all these great movies. He signed them all over—lock, stock and barrel—for loans in the future. And then they called in the loans. And then he didn't have the distribution necessary...and when you can't pay the bank, the bank comes and takes your marbles away. BJH: Given the distribution difficulties facing Hemdale at the time, what was that like for you—as a producer? GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: At one point, John [Daly] called me and says, "George, there's no belly laughs in this movie! We need someone to go out and, like, set a paper bag on fire that's got some dog shit in it. Or something." BJH: [laughs] GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: "We gotta get some American humor going. And if you don't put some belly laughs in there—we're trying to make a comedy for an American audience; not a refined English audience—you're fucking fired, pal! I need someone in there to give me a comedy with belly laughs so that the distributors, or exhibitors, are laughing their head off." I said, "Well, John...what's funny for one person isn't funny for another. And we have a script. We have a book. We have a script based on a book and it's not, you know, pie-in-the-face-type stuff." [But] you know, I had a duty to talk [to the cast and director].BJH: Of course. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: So I get Guttenberg and I get Shelly and Malcolm and I say: look, I don't know how to do something like that. I mean, you have a script; you have sets; you have a budget, you have a schedule; what are you gonna do? Bring a comedy writer in from TV and start writing blackouts or something? It wasn't possible to do. And John and Derek were frustrated because they didn't have distribution. So without distribution—without platforming a picture they were fucked, you know? And they thought, well, maybe if George can deliver some belly laughs, maybe he can save the company. BJH: Right. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: So we all agreed that it was an impossible thing that John asked me to do. I went back and I said, "John, I talked to everybody, and I talked to the writer too, and there's just nothing we can do." He says, "Okay. Pack your fucking bags, asshole. You're fired. I'll be out there on Monday and I'll do it. I don't need you to do it. It's my money, it's my company, I'll do it. I'll tell 'em what to do." BJH: Gotcha. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: [laughing] So I went back and told everybody what John had told me. Shelly was the first person—she said, "George, I'm you're going, I'm going." Steve said, "I'm going." Malcolm said, "I'm going." The cinematographer said, "I'm going." And the sound man said, "I'm going." So I called John back and said, "John, it's all here waiting for you when you come out on Monday...but unfortunately, when I'm gone, everyone's going with me!" And there was silence on the other end. And then John said, "Just finish the fucking movie!" And hung up on me. [laughs]BJH: Wow. That's a great story. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: That was kind of the way it was. Then we finished the film. John didn't have distribution and the lack of distribution was probably the death knell to one of the most successful production companies of all time. I mean...John Daly, Derek Gibson and Hemdale will go down in my mind will go down in history. Because they were mavericks and they just...and I think because they were Mavericks, people were jealous of them. Studios would spend more money than God and not get an Academy Award. And John would do things cleverly and won Academy Award after another. He was really a genius. And a great guy. John Daly passed away in 2008. He was 71 years old. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: I think part of the reason John Daly was such a genius (and I credit Derek Gibson with a lot of this too) is because he was a fight promoter, man. BJH: I didn't know that. GEORGE BRAUNSTEIN: Yeah. And the movie business is not "oh, let's have tea and crumpets." The movie business is getting down into a mud pit and battling for exhibitor dollars—it's battling for dollars out of people's pockets; it's battling for eyes on a TV screen. It is warfare...and John knew that world. He came from the prize-fighting world and he understood where it was at.