'Neon Genesis Evangelion' And The New Religion Of 21st-Century Fandom

Fandom is a religion that thrives on killing its own gods. In Neon Genesis Evangelion, there's a passing line of dialogue that suggests self-destruction is the natural endpoint of evolution. The Japanese television and film series periodically evokes deicide with exotic Judeo-Christian imagery, such as god-killing spears and figures nailed to crosses. Yet it's known for the line, "The fate of the destruction is the joy of rebirth." Evangelion is a franchise that evolved to the point of self-destruction, only to be reborn, or rebuilt, numerous times over. Its latest rebirth is on Netflix, where it became available to watch last Friday.

The ability to conveniently view one of the greatest anime works of all time should be cause for celebration among U.S. fans, whose main avenue for watching the series since the DVDs went out of print years ago has been illegal streams, expensive copies from third-party Amazon sellers, or the sketchy online market of bootlegs. Due to licensing entanglements, however, the situation with Evangelion has come to resemble Star Wars, whereby the original, unaltered theatrical trilogy is unavailable on home media. Here again, the version that is out there for mass consumption is different from the one fans first experienced, with redubbed voices, new subtitles, censored relationships, and missing music.

The reaction on social media had been typically harsh, enough so that it almost plays right into Evangelion's metaphorical god-killing cycle, as complaints drown out discussion of the anime epic's lasting virtues and the baby gets thrown out with the bathwater all over again. What's important is that the series is catching a wave of renewed interest, and as it finds a fresh audience, it's ripe for discussion, particularly as it relates to themes of personal dysfunction, social withdrawal, and the intersection between fan culture and storytelling.

This article contains spoilers for the entire series.

The Evangelion Bible: New Revised Netflix Version

In Neon Genesis Evangelion, the fate of the world rests on the shoulders of a lanky mech piloted by a 14-year-old. If Shinji Ikari could just manage to get his act together, he might actually be a hero. As it is, he's a self-loathing mess who is often depicted hanging his head in shame and who is likely to strike some new viewers (or even old ones) as a pathetic protagonist. But really, that's the whole point.

Creator Hideaki Anno's struggle with depression deeply informs the character of Shinji, just as end-of-the-world fears fuel Evangelion, an easily binge-able, 23-minute show that began its run on Japanese television in 1995, months after a devastating earthquake struck the city of Kobe and a doomsday cult carried out the Tokyo subway sarin attack. As a resident of Tokyo, I may have a slightly different perspective on the Netflix iteration of Evangelion, especially since my day job is that of a language teacher, meaning that much of my existence revolves around the fluidity of words and their meanings. In general, I think that once a thing ceases to be fluid and starts to become rigid, it's as good as dead.

Years ago, before leaving the states, I divested myself of all DVDs, abandoning physical media for digital purchases via the iTunes Store. This included my eight-disc Neon Genesis Evangelion: Perfect Collection set, as well as my copies of the two movies, Death and Rebirth and The End of Evangelion. In college, those movies, along with the 1988 classic Akira, were my introduction to anime. The End of Evangelion, in particular, left me thunderstruck with its apocalyptic imagery, and to this day, it remains my favorite anime film.

I always just sort of took it for granted that if wanted to, I could go out and buy Evangelion on Blu-ray at a store in Tokyo. Not everyone has this Blu-ray option at their disposal, and I can appreciate how frustrating that might be. This week, I mounted my Evangelion rewatch on Netflix Japan, where the integral outro song, "Fly Me to the Moon," was intact at the end of every episode. As a fan of "Ewok Celebration" (a.k.a., "Yub Nub," the original song at the end of Return of the Jedi, before it received the Special Edition treatment), I can appreciate, also, how stateside Evangelion fans would decry the loss of "Fly Me to the Moon."

With the Netflix translation of Evangelion, there's been a lot of hand-wringing about the changing of certain lines of dialogue, too. That didn't bother me any more than it would if I was at the bookstore and saw a new translation of a classic work of literature like Dante's Inferno (which, in the Rebuild of Evangelion film series, helps furnish the levels of Nerv's Bethany Base with names, so that they sound like the Circles of Hell.)

Again, I can understand the disgruntlement about seemingly unnecessary changes. Texts like Evangelion become as sacred as a bible to some fans, which is fine until you stop to think that the actual, you know, Bible-bible has been translated and re-translated, interpreted and re-interpreted, ad nauseam. Which is the "correct" translation (if there even is such a thing): the King James Version, the New Revised Standard Version, or one of the other innumerable versions? The way I look at it, only a literalist or fundamentalist would get so caught up on the details in a book of parables that he or she missed the point of the parables entirely.

Evangelion is a parable about a dysfunctional human being and his fumbling attempts at being a participant in life, which eventually lead to a burgeoning selfhood on his part. Shinji Ikari was born to pilot an Eva ... he just doesn't know it right away. No sooner does he arrive at Nerv Headquarters in the first couple episodes than he's having to leap into the fray with zero experience.

At that point, he can barely walk in his Eva. We're initially led to believe that his first at-bat proved disastrous, as it cuts from the Angel pummeling his Eva on the battlefield to him waking up under the "unfamiliar ceiling" of a bleached-out hospital room.

The twist comes when there's a flashback later, revealing that he won the battle and is a something of natural when it comes to Eva piloting: able to tear through glowing force fields, or A.T. Fields, and dismantle his Angel opponent. If only that could cure loneliness...

Shinji Ikari, God’s Lonely Man

Shinji craves approval and when he doesn't get enough of it, his efforts leave him hollowed out, going through the motions of shooting a gun while robotically repeating the words, "Center the target, pull the trigger." In his new bunking place at Misato's apartment, he lays on his bed, replaying moments from the day's interactions in his head. He can't even bring himself to unpack the boxes in his room. He spends much of the time with his ears walled off by headphones, listening to music, playing and replaying tracks 25 and 26 on his Walkman, as if Anno already somehow knew that he would one day cycle back on those same episode numbers with Evangelion.

Shinji runs away from Nerv, attempting to quit, only to return and face the same hedgehog's dilemma whereby the closer he gets to people, the more he gets hurt. Quiet at dinner parties, he just doesn't know how to act around people, we're told. He has a growing network of acquaintances but he's "the sort of person who can't make friends easily." At school, he gets punched around by his own Flash Thompson, Suzuhara, who goes from bullying him to being his most vocal cheerleader and eventually his unwitting victim in an Eva-on-Eva fight.

Like his aloof father and his fellow pilot, Rei, Shinji is simply "all thumbs at living." He undergoes "unison training" with Asuka, but he's perpetually out of synch with her and the world around him. The one constant is that he endeavors to please his father and people in general, yet as his new friend (maybe, first real friend) Kaworu notes toward the end of the series, he goes to extremes to avoid making first contact with anyone. If he avoids other people, he'll never be betrayed.

Not realizing that "people can't handpick a series of pleasant events to make up their lives," Shinji has (again, we're told) spent his whole life ignoring or avoiding anything he doesn't like. In this respect, he's maybe cut from the same cloth as the rest of the Tokyo-3 populace. Fuyutsuki, who serves as a second-in-command to Shinji's father, describes the city as "a paradise we built for ourselves to insulate our kind from the terror of death and satisfy our carnal desires" It's a city of cowards, he says, "shelter for those fleeing an outside world full of enemies."

As the series progresses and Shinji's confidence as a pilot takes shape, being inside the Eva, taking up the fight against the Angels — wrestling with these gods — is how he comes to justify his existence. It's not so different from the life of an otaku, Japanese, American, or otherwise, who seeks fulfillment in his or her own fandom, saddling up street-side in a lawn chair to cheer and heckle the procession of pop culture giants, year after year. Maybe Shinji's there along the parade route, too: "just sitting around, waiting for someone to bring false happiness to him."

Shinji's not the only one who lives to impress the father who abandoned him. When Misato talks about her father, she describes him as, "A man who lived in his own dreams. A man who was absorbed in his research. A spineless man who couldn't stomach reality." Then she realizes that she and her father are just like Shinji and his father.

Gendo Ikari never paid any attention to his family, either. It left his motherless child struggling to fill the hole in his heart where a parent's love should have been. Asuka pointedly teases Shinji about this, asking him if being in the entry plug of his Eva feels like being back in the womb. On the outside, an umbilical cable connects his unit with a power source, while on the inside, said entry plug is filled with LCL, a breathable liquid that surrounds Shinji like amniotic fluid.

Fans are weaned on a steady diet of pop culture; Shinji is weaned on a succession of Angel battles. One of those battles ends with his Eva going berserk and eating the Angel it has defeated. Shinji has already learned to miraculously reactivate the Eva unit after it has detached from its umbilical cable and its 5-minute power supply has run down ... but when it devours the Angel, it also absorbs the Angel's engine, giving it a new source of unlimited energy. For the first time, it and its young pilot stand truly self-sufficient.

The Fan That Shouted “I” at the Heart of the World

Shinji's ability to stand on his own brings to mind a speech that Ritsuko gives in the Dummy Plug Plant, right before she destroys the tank full of floating Rei clones. It's a speech that's key to understanding Evangelion as a kind of geek empowerment document, whereby the fan evolves from a passive viewer to an existentialistic participant and finally a potential creator. We have no ownership over this work but we're free to ascribe meaning to it and use it as inspiration for our own creations:

"Mankind stumbled across God. Overjoyed, we tried to possess it. And so, we were punished. That happened 15 years ago. The God we were so excited about vanished. Undeterred, we then tried to resurrect God. That was Adam. We made humans from Adam in God's image. Those are the EVAs. ... The EVAs are intrinsically soulless, so we imbue them with one. They're cobbled together with salvaged material."

Evangelion is full of quasi-religious babble, but read euphemistically, with "God" substituting for art, this whole speech can be seen as a description of people trying to recapture the magic of the art that once moved them. As fans, we stake our claim on stories that inevitably conclude and leave us searching for the next source of inspiration. Maybe some fans, like Anno, respond by cobbling together salvaged impressions into their own artistic constructs.

It's no coincidence, perhaps, that "Eva" is a shortening of Evangelion, the very title of this tale. On one level, the battles with Angels can be seen as Anno — the otaku, or obsessive fan, turned artist — contending with his own influences, the creative and philosophical giants that came before him. In order to make this piece of art come to life, however, he needs to imbue it with a soul, and that's where Evangelion's fans come in.

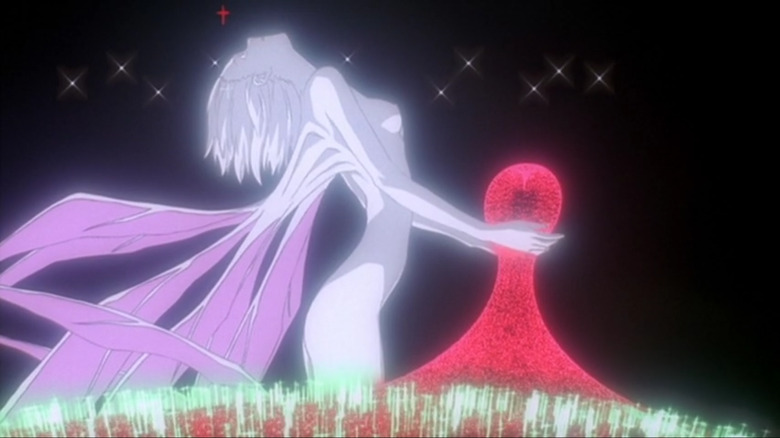

Below it all, there's the strange, seven-eyed figure of Lilith, who hangs on a red cross deep underground and seems to draw the Angels to Earth. Lilith functions as the captive monomyth in this story about stories and how we relate to them.

Fandom is hardly a new thing, but the rise of the Internet in the 21st century has mobilized it like never before, giving it a more proprietary and domineering, if not outright controlling influence on the media it consumes. On this front, Evangelion strikes me as having been years ahead of its time. This is a show that literally redid its own ending after fans were dissatisfied with the first one they got. Just last month, with a petition that gathered over a million signatures, we saw Game of Thrones fans lobbying for their favorite show to do the same thing.

Thrones is a show that was mired in the male gaze; Evangelion, too, indulges in a fair bit of scopophilia, lingering in frame on cartoon female anatomy, lifting up characters like Misato and Rei as purple- and blue-haired lust objects for Shinji and the viewer. Early on, the whole living-with-Misato scenario turns the vivacious 29-year-old into a surrogate mother who is a focus of Oedipal desire for Shinji and the other hormonal teenage boys at his school.

It's all part of the fan service (bearing in mind that this term originally had more of a sexual connotation to it, as it applied to pieces of entertainment like Evangelion, which started out its life by pandering to a base of mostly male otaku in Japan). When not playing the titillation game, the show employs tongue-in-cheek sight gags and other bawdy humor. Episodes end with the words, "Tune in next time for lots more fan service!"

Gratuitous as they are, Evangelion wields these tropes as genre staples. The series is as much an extension of the anime tradition as it is an extension of its creator.

After delivering his original, small-screen ending to Evangelion, Anno received death threats; some of these are shown onscreen in The End of Evangelion. Such threats have become yet another unfortunate byproduct of fan culture in the franchise-filled new millennium, as viewers looking to hold someone accountable for their disappointment lash out online at filmmakers and showrunners. This is the dark side of fandom, whereby the rabid fan goes truly feral and becomes the titular "Beast Who Shouted 'I' at the Heart of the World."

Entertainment as the Opiate of the Masses

Clearly, Shinji Ikari fits the profile of a certain breed of introspective fan. Adventuring in his Eva is his substitute for socializing and forging meaningful connections with people. In the original ending to the Evangelion series, episodes 25 and 26 (cue Walkman), we get lost inside Shinji's headspace and that of other characters as the Human Instrumentality Project threatens to bring about the loss of individuality, merging all human souls into one gestalt, super-evolved entity.

These characters have always been separated by their own Absolute Terror Fields, inner walls that represent "the light of the heart." But now the walls come tumbling down and the series descends into the pit of its own navel, with each character gazing deep at his or her true self as the voices of others begin to intrude on their headspace. In among the flashing words and visual abstractions, there are nuggets of profound insight. The voices tell Shinji, "You wished for a closed-off world that's comfortable for you and only you. To protect your fragile heart. To protect your pleasure." But "people can't live in a closed-off realm."

He's forced to examine how he has used the Eva as a means from escaping reality. We often speak of cult followings in entertainment, but that old bit of Marxian paraphrasing, "Religion is the opiate of the masses," takes on new meaning when you think of fandom as a nascent religion—one for those who have none, like Anno, who identifies as somewhat of an agnostic.

The problem, for Anno, develops when one's fix of self-medicating entertainment becomes a dependency. Strip away the drip-feed of anime or comic book movies, and what does a fan have left? Is it enough? "You have no identity outside of being a pilot, do you?" one of the voices asks Shinji. Another says, "If you become dependent on it, the Eva will dictate who you are. Your identity will be defined entirely in terms of the Eva."

It would be easy to see all of this as a repudiation of fandom, as if Anno were somehow chastising his audience for liking this thing he's put out into the world. However, he was working through his own issues with Evangelion, using the series as a form of personal therapy, perhaps seeking to overcome his own "myopic worldview" as an escapist and to heal a "heart that perceive[d] reality as being ugly and painful."

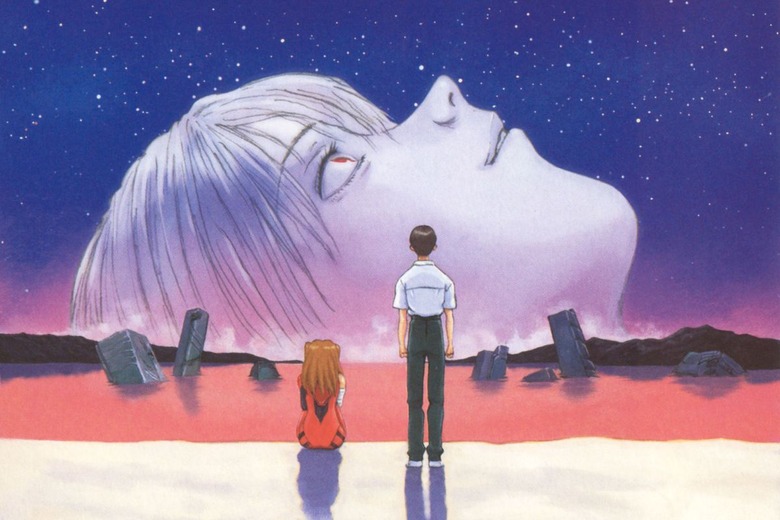

It's important to remember that even in The End of Evangelion, Shinji chooses to retain his individuality along with all the joy and pain it encompasses. He doesn't get the same round of congratulations that he did in the original TV ending, but that's only because the world's population has been reduced to a primordial soup, leaving him and Asuka to make a fresh start as a new Adam and Eve, the last man and woman on Earth.

There are no more Angels left for them to fight. Now there's just the business of being human, finding meaning in a world where the old structures underpinning duty and comfort have collapsed.

The Gospel of the New Century

As I was writing this analysis of Neon Genesis Evangelion, I had a Shinji moment, where I was filled with self-doubt and started to wonder if I was off-base with my interpretation. It's a work that's densely layered and maybe I was just reading things into it that weren't there. Searching around online for other perspectives, I came across a post on The Artifice with a view that mirrored mine. Titled, "Otaku as Artist: Hideaki Anno and Neon Genesis Evangelion," it notes how Anno "began his career by embracing his identity as an ardent anime fan, and later formed the thematic arc of his premier work around his evolving relationship with the Otaku lifestyle."

There's another quote that neatly sums up my view of Evangelion and the lessons it holds for the new religion of 21st-century fandom:

"Shinji Ikari's story has much in common with the millennial narrative at large, because Evangelion essentially charts his struggle within a world that threatens to discard him for not serving it in a specific way. In order to reclaim his sense of self, he must first overcome a deeper psychological dilemma. He must stop using fantasy to escape the real world, and instead use his imagination proactively, to create a better reality for himself and for others."

When I first watched and rewatched Evangelion, all those years ago on DVD, my comprehension of Japanese was limited to about five words: konnichiwa and sayonara, ohayo (easy to remember because of Ohio), gaijin (a word I picked up from Wolverine comics), and of course, the ever-popular, "Domo arigato," (as immortalized by the Styx song, "Mr. Roboto.") That made it very surreal to reunite with the series this time around, given that I'm surrounded by the language now on a daily basis.

I was aware before that there was some debate concerning the last line of The End of Evangelion and how it should be translated into English, but when I got to the end of the rewatch this week and heard Asuka say, "Kimochi warui," it was like realizing that a piece of linguistic lint I had pocketed was, in fact, an important puzzle piece. I say that because, "Kimochi warui," is such a common phrase in Japan — you hear it all the time in a variety of situations where people are grossed out or feel nauseous or think something is creepy — but I didn't know that before I lived here and so it didn't stick with me that those specific Japanese words were the last line of Evangelion.

It's an old message-board argument, but which translation do you prefer, "I feel sick," or, "How disgusting?" The very fact that there's room for debate and that each translation carries a different meaning makes it the perfect last line, ending the series on a note of ambiguity, leaving it open to interpretation. There's no one "right" interpretation of Neon Genesis Evangelion, but with everything said here, one last point of consideration might be the very title of this anime masterwork.

Translated literally, the Japanese title, Shinseiki Evangelion, means, "The Gospel of the New Century." With this story, Hideaki Anno shared his vividly colored testament of life on Earth, inviting fans to go forth and share their own gospel. You don't need a mech to do it.