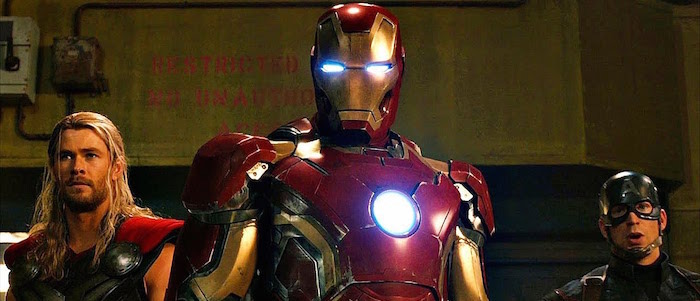

Road To Endgame: 'Avengers: Age Of Ultron' Balances The Legacies Of Gods, Monsters And Human Beings In One Marvel's Most Underrated Movies

(Welcome to Road to Endgame, where we revisit the first 22 movies of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and ask, "How did we get here?" In this edition: Avengers: Age of Ultron digs in to the superhero's religious subtext)Avengers: Age of Ultron is a big ol' action beat-'em-up between superheroes and robots. It also uses genre trappings to dramatize the creation of God and the Devil, in order to tell a story about why we create, and why our stories matter.By 2015, our entertainment landscape had become dominated by violent Übermensch in visages of childhood fantasy. DC's Man of Steel, which attempted to reframe one of pop culture's premier icons two years prior, caused widespread debate about civilian casualty and the role of the superhero. As if in response to that conversation, Avengers: Age of Ultron placed similar debates in its crosshairs; first, by making its characters re-establish their objectives — the protection of individuals — and second, by challenging their methods.This narrative not only helped set up future installments, it also forced the Avengers to contend with their in-world legacies as a means to explore the series' legacy on-screen. The Marvel Cinematic Universe is the most successful franchise in history, and so a $300 million blockbuster that acts as genre self-critique (to varying degrees of success) is noteworthy.

Would You Sacrifice Millions to Save Billions?

Through most of the series, our heroes have responded to this question with a resounding "No." In The Avengers, they stopped a nuclear attack on New York City meant to prevent global invasion. In Captain America: The Winter Soldier, they opposed H.Y.D.R.A.'s plan to use mass murder as a shortcut to peace. Even on a personal scale, the Avengers have always leaned toward altruism; in Thor, Captain America: The First Avenger and Guardians of the Galaxy, heroes sacrificed themselves rather than letting a single person die.When villains decide to trade lives, the heroes' decisions are clear. But what if the Avengers were forced to choose between atrocities of their own? In the aforementioned films, the heroes were only ever tasked with stopping someone else's weapons. In Avengers: Age of Ultron (and Avengers: Infinity War, for that matter), they're forced to confront a superhero Trolley Problem, a conundrum designed for the express purpose of bringing their violent natures to the surface and proving their futility.Tony Stark (Robert Downey Jr.), a futurist who repeats his past mistakes in newer, greater iterations, creates the Artificial Intelligence Ultron (James Spader). Ultron's mission, logistically speaking, is peace. But it's peace without conscience — not unlike H.Y.D.R.A.'s "Project Insight," or Thanos' snap — a utilitarian peace, divorced from empathy. Ultron has the tools to build and destroy, but he's a reflection of the Avengers without their protective instinct (Their humanism is eventually granted to J.A.R.V.I.S., Stark's personal A.I., reborn as Ultron's foil).Ultron's idea of harmony is a world where humans can no longer do harm. Like the Mad Titan Thanos in Infinity War, his answer is genocide.As if in response to criticisms of the genre, Tony Stark now uses non-lethal means to incapacitate soldiers; he even scans a building for civilians before tossing a rampaging Hulk into its structure. However, this more cautious M.O. doesn't ignore what came before. Ultron still deems the Avengers unworthy of heroism, since they've all killed at some point. A simple course-correction isn't enough; there needs to be reckoning.To prove the futility of human heroes, Ultron raises the country of Sokovia miles in the air and plans to drop it like a meteor. The result would be human extinction, but the Avengers destroying Sokovia before rescuing every one of its citizens would be catastrophic too.Avengers: Age of Ultron is the O.M.A.C. Project film we may never get from DC, a story of global security A.I. run amok, calling into question the responsibility of superheroes and their use of lethal force. It's also the closest thing to a big-screen adaptation of Warren Ellis and Garrie Gastonny's Supergod, in which humanity creates superheroes as weapons of war, but fashions them in the image of religious deities — as if our need to create, and our need to believe that we were created, are intrinsically bound.The seeds for the film's massive third act are planted throughout, with each Avenger having to contend with the nature of their past, and how their actions might dictate their future. As much as Age of Ultron is about holding on to the idea of humanity in the face of a soulless being, it's about why these specific heroes must re-establish their own humanity if they're to be worthy of heroism, and their stories worthy of telling.

Avengers Disassembled

The film opens with a single, unbroken take following the Avengers through the forests of Sokovia as they dismantle H.Y.D.R.A.'s remnants. The visual language evokes the sprawling long-take between skyscrapers in The Avengers, which arrived soon after the team first learned to work together — video essayist Patrick Willems compares this to the use of splash-pages in comics. Three years on, the Avengers are introduced in their sequel as a well-oiled machine, before being scattered by the rest of the narrative.Loki's scepter from their previous film — revealed to be an Infinity Stone — is being used for human experiments, and the Avengers believe it's their job to intervene. The citizens of Sokovia, however, aren't pleased by this largely American outfit launching attacks on their soil. Sokovian graffiti portrays The Iron Man as a war profiteer, clutching guns and money in the background while his drones dictate terms of safety. The Avengers function as a singular unit, but do they function within the world at large?The team is brought together by a desire to do good, but they're torn apart when Wanda Maximoff (Elizabeth Olsen) unearths their deepest fears. Her scepter-derived abilities fill our heroes' heads with nightmares; Tony Stark sees his friends dead at his feet, after Earth is left vulnerable to invasion. He's unable to shake the idea that he should be doing more to prevent future catastrophe, so he proceeds to create Ultron without consulting the team.Steve Rogers (Chris Evans) finds himself at an end-of-war party in 1945 — the kind of peaceful day he's never seen — forcing him to question his place in a world without war. Even if he can return to wanting love, a home and a family, things that were lost to him decades ago, would he be able to stop seeing evil and conflict at every turn? Spilled wine turns to blood, and a celebration turns to violent disagreement. Rogers' experiences have left him too paranoid for a peaceful world, and too afraid of a sense of normalcy.Iron Man has seen what happens he isn't prepared. Captain America knows how even peacekeeping forces can be used for harm. While Tony Stark accelerates the path to peace, Steve Rogers begins to question it at every turn.Once our heroes inadvertently wreak havoc in Johannesburg, they're forced to lay low at Hawkeye's farmhouse. This detour was almost cut from the film, but director Joss Whedon was right to fight for it. Given the dire circumstances, the Avengers spending quiet, contemplative moments together helps focus the story at hand.

Gods and Monsters

After three film appearances, Thor (Chris Hemsworth), the God of Thunder, is finally faced with the consequences of his warmongering. During his hallucination, he sees his countrymen cast to Hel, the Asgardian underworld, as his full destructive potential comes to the fore. Even once he snaps out of his trance, he's rattled after treading on a child's toy house, while its owner, Hawkeye's daughter, looks up at him. His legacy is ruination.While Thor's removal from the narrative is inelegant, the questions posed by prior films — both directly and through omission — still remain. Can Thor use his hammer to protect? Can this destroyer be compelled to create? He does, bringing to life The Vision (Paul Bettany) and choosing to trust in him, but is this leap of faith enough?Thor's compatriots Bruce Banner (Mark Ruffalo) and Natasha Romanoff (Scarlett Johansson) however, don't have the luxury of creating in order to atone for their pasts. Their first encounter in The Avengers took place beside an empty cradle. In Age of Ultron, their most vulnerable exchange occurs in the room of one of Hawkeye's children — with Hawkeye's pregnant wife just doors away — as they wonder if parenthood, or peace of mind, is something their destined for, or something they deserve.At times, the actors' romantic dynamic feels forced and awkward. Their chemistry doesn't quite work; then again, nor should it. Both in their initial flirtations ("And here comes this guy, spends his life avoiding the fight") and in their private confessions ("Where can I go? Where in the world am I not a threat?"), the characters are brought together not so much by mutual interest, but by a shared desire to escape — both the larger conflict, as well as their own legacies.Romanoff, having had her world turned upside down in Captain America: The Winter Soldier, has trouble seeing herself as a hero. The Hulk regularly endangers civilians, and rather than a dream or vision, we see his fears manifest in the form of a rampage. Having taken and endangered countless lives, both characters see themselves as monsters.They're also both unable to procreate. Banner might endanger a sexual partner, or pass down his irradiated blood. Romanoff was sterilized by the K.G.B., since fewer attachments meant easier killing. They believe this gives them one less chance at bringing something good into the world. Like Thor, all they leave behind is destruction.And finally, there's Hawkeye (Jeremy Renner), the most stable of the bunch, and the only Avenger whose legacy is clear. Clint Barton remains unbroken by Wanda. He's forced to take on a paternal role and keep the team together, despite their awareness (and his) that he's the most expendable Avengers. Unlike the others, we don't ever see him experience his greatest fears first-hand. But we know what he fights for: the wife and two children (soon to be three) whom he's carefully hidden from the world.Barton is the film's most grounded character. He provides the story with a human perspective, but just a few scenes in, he has part of his torso synthetically replaced. He claims to feel the same, but his wife can tell the difference. He is, in microcosm, an embodiment of the Theseus Paradox the Avengers now face. In creating Ultron, another artificial being, Tony Stark re-assembles puzzle pieces of humanity and heroism in a form resembling a protector. The result, however, is something uncanny: a reflection of the Avengers' physical selves without the presence of a human soul.

The End of the Line

Each Avenger is tested in the film's final battle. No amount of preparation or scientific process can help Stark out-think the problem. In The Avengers, saving the day came down to his singular decision, when he flew a missile through a wormhole. Here, for once, the self-proclaimed leader has to rely on the rest of his team, hoping they'll ferry everyone to safety before he's forced to destroy Sokovia.Steve Rogers is placed in a seemingly impossible position: letting the world end, or killing a few thousand civilians in order to save it. Yet he doesn't abandon his post, choosing instead to go down with the ship, because he would rather die than compromise. Romanoff, the only Avenger who refuses to try and lift Thor's hammer, stays by Rogers' side, finally choosing to stand her ground rather than running from the question of her worth.While the resolution to Rogers and Romanoff's last stand feels too narratively convenient — the remnants of S.H.I.E.L.D. show up in Helicarriers to rescue civilians, preventing the duo's decision from being dramatized through action — the moment remains impactful, because it's where both their stories culminate. Captain America remains uncompromising in this grey new world, even in the face of extinction. Black Widow finally stops being defined by her past, and rather than running away from the killer she once was, she decides to pay her dues and wipe the red from her ledger.Upon appearing to the Avengers for the first time, Ultron questions how the group could be "worthy" if they've been killers. Romanoff's stand is the answer, as is S.H.I.E.L.D.'s heroic re-emergence after being twisted into a killing machine in Captain America: The Winter Soldier."This is S.H.I.E.L.D.?" asks speedster Peitro Maximoff (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), whose only context for American power thus far has been the bombs dropped on his family. Steve Rogers responds: "This is what S.H.I.E.L.D. is supposed to be."

The United States of S.H.I.E.L.D.

After the series bungled its American military metaphors on numerous occasions, including and especially military-funded entries like Iron Man, Iron Man 2, Captain America: The Winter Soldier and Captain Marvel, Avengers: Age of Ultron's employment of metaphor feels less like shifting the blame for American war crimes, and more like a logical narrative extension.The Avengers are no longer a band of rogues. They're a fully-equipped, billionaire-funded paramilitary unit, self-appointed saviours carrying out foreign operations with relative impunity. When the film kicks off, they seem to have enough support (or lack enough government opposition) to operate independently.The graffiti of Iron Man clutching cash and rifles was as much Sokovia's criticism of the Avengers as it was the series beginning to introspect. This is both how a fictional European nation sees Iron Man, and how most nations around the world (especially those under U.S. military occupation) view American power. The camera never points to the actual American military as a superior in-world alternative, the way several other Marvel films have done. Granted, the film doesn't frame the Avengers as having foreign political interests either, so the metaphor is imperfect, though it's a significant improvement over the majority of the series (especially the entries that happen to be literal government propaganda).Captain America, in his stars and stripes, looks up at warships whose guns have been replaced by lifeboats; a reflection of his own ideals, as man whose only weapon is a shield. "This is what S.H.I.E.L.D. is supposed to be" is as much a winking line about the Avengers as it is about the United States; the metaphor is framed to be aspirational, rather than to deflect real-world blame.While the re-appearance of S.H.I.E.L.D. dissolves much of the tension for characters like Rogers and Romanoff, its metaphorical function speaks to the larger idea of trading lives; for instance, in a historical context. To this day, the United States justifies killing hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians to save millions of Americans — the dropping of A-Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 — a position the Avengers are now forced into. However here, the remnants of an American military outfit show up to help circumvent that dilemma; if this is what America is supposed to be, then the idea of trading lives on this scale ought not to even be entertained."This is what S.H.I.E.L.D. is supposed to be" is also a statement rooted in character. Captain America's trust in authority structures has all but been eroded — with good reason, given the events of The Avengers and Captain: America The Winter Soldier — thus setting up the conflict in Captain America: Civil War. As the grounding point for the series' overarching morality, Steve Rogers acts as an apologetic mouthpiece for the Marvel Cinematic Universe here, expressing something the Avengers have thus far failed to: a desire to improve the status quo.While the heroes constantly fend off external threats, they rarely seek to better the equilibrium. This wishful throwaway line from Steve Rogers is the rare exception. Even though the rest of the series is yet to follow up on it — Black Panther aside — Rogers hints at the kind of better world he might someday hope to create. This makes him not only a beacon of heroism, but a human grounding point for the film's own views on creation.

Creation

While Captain America is a fixed moral point, and Black Widow's arc culminates in self-actualization, the other Avengers fulfill more allegorical functions. To save humanity from Ultron, an omnipotent, omnipresent force with the destructive impulse (and retributive disposition) of the God of the Old Testament, Thor, Banner and Tony Stark create a divine being in the form of The Vision.Stories are usually the sum of their creators. Their thoughts, their hopes, their perspectives — often conflicting ones, as articulated by this video essay by Cameron Carpenter on the film's Biblical allusions. Creating is one of the ways we leave a part of ourselves behind; a legacy, made tangible.Creating Ultron and The Vision are the logical extension of Tony Stark's God complex. He creates a fallen angel before creating a savior — as if to re-write his gift to humanity — though Stark's story here is also akin to that of a storyteller wrestling with a conflicted worldview.Stories help us make sense of the world; concepts like God and the Devil, or any governing forces of Good and Evil, stem from that very instinct. The world is chaotic, and we create our own mirrors to bring it into a form resembling order. The same can be said of Tony Stark, whose hallucination feeds off his fear and P.T.S.D., throwing him deeper into his obsession to encase the world in armour. In order to do so, he needs to create, but he first creates from a place of fear and isolation. He sees bringing order to the world as his sole duty, regardless of what the world might think, and so he flirts with pure utilitarianism for the first time since Iron Man. The result is more important.In his cynicism, Stark fashions a being that absorbs only the worst in humanity, reflecting it back to him tenfold. Ultron, in his infancy, learns about humanity's destruction without learning about humanity itself. He understands the art of war, but can he appreciate art?Tony Stark's second creation in the film comes from a place of understanding. While Stark has no control over how The Vision will turn out, he creates him by using J.A.R.V.I.S., a program written explicitly to protect. This is the same A.I. that has been looking after Stark all these years, and an A.I. that, even when seemingly destroyed, followed its base protocol and shielded the world from nuclear attack.Rather than being created cynically, or in secret like some Frankenstein's monster, The Vision feels divinely inspired. He's made from Iron Man's technology, Thor's otherworldly lightning, Banner's engineering, and the same material Captain America uses for a shield — like a collaboration born out of conflict, wherein each creator shares a common goal.The result is a being who speaks with kindness, and whose every movement is graceful; the other side of the Ultron coin. The Vision ascends to the sky in a golden cape, not unlike the heroic Yellow Emperor of the Taoist religion, who rose to heaven in plain sight on the back of a golden dragon. Whereas magician Ye Fa-shan, another prominent figure in Taoist views on death, was said to have turned his own corpse into a sword, the way Ultron replaces his old bodies with newer, more destructive ones.Even if these specific parallels to Taoist shijie (or transformation in death when one's spirit is released) were accidents, they speak to the themes of balance at the heart of Taoism, whose symbols the film explicitly references.

Yin And Yang

When Sokovia is lifted into the air, it cracks along a specific trajectory. Half the meteor is a dark forest. The other half is white marble. The curvature of the border between the two resembles the Taoist yin and yang. Nature, and manmade structure, in perfect balance, like the opposing light and dark within all people, each giving rise to the other.Ultron and The Vision represent competing schools of thought on humanity. They act as opposing narrative forces, pushing and pulling the world between their respective desires. Ultron sees destruction as the only path to salvation. He's an externalization of Stark's violent past, unintentionally quoting him from his days as an arms-dealer ("Keep your friends rich and your enemies rich, and wait to find out which is which"). He has Stark's sense of humor, but he also has Stark's condescension — that is, the condescension of the pre-Iron Man Tony Stark — thus embodying the very worst parts of his creator.The Vision however, accepts humanity's imperfections. Like Captain America, his mission is not to kill, but to save. He claims to be "on the side of life," an affirming reminder of what the Avengers' objective ought to be. These competing narratives will determine not only the fate of humanity, but who the Avengers are at their core. Should they fail, they'll fall in line with Ultron's view of the world, wherein humanity is only capable of destruction, and deserves to be replaced by a perfect race of soulless, metallic beings. From that point on, stories themselves will cease to matter.But should the Avengers succeed, despite their many failures in the past, they'll align with The Vision's outlook, which he explains to Ultron in the forest: order within chaos, grace within failure, and of the beauty of human imperfection. The idea that people can still be good, even when intrinsically flawed.The dichotomy between Ultron and The Vision is very basis of storytelling throughout history. It cuts to the heart of conflicting human impulses: to create chaos, and to cede to it; to control, and to be controlled; to create divine beings, and to believe that were divinely created. Dualities we cannot begin to reconcile until we self-actualize through our own stories, drawn from our pasts and written with an eye toward our futures.Ultron and The Vision are abstract extremes. The Avengers are imperfect beings who fall somewhere in between them. Ultron's army of thousands may be in perfect harmony with one another, but they're eventually bested by the varying abilities and perspectives of our discordant heroes.The Vision may lift Thor's hammer by virtue of his divinity. But at the end of the day, as if to justify an otherwise imperfect narrative formula, the film's quippy, comedic scenes brimming with camaraderie, like the Avengers trying — and more importantly, failing — to prove their worth, are what make them feel human.

***

Expanded from an article published April 16, 2018.