A Simple Rule Made Sure Buster Keaton Could Always Throw In Some Improv

Buster Keaton was one of the biggest names in early cinema, famous for his physical comedy. He thrived on an ability to improvise these gags; Keaton grew up as a vaudeville performer, and spent his childhood improvising slapstick routines with his father onstage. As a Hollywood filmmaker, Keaton continued to rely on improvisation for his comedy — but this required him to follow one simple rule.

Keaton got his start as an entertainer traveling in a company alongside Harry Houdini. It was here that he learned to improvise fluidly and hilariously. His first time in front of a camera was in Fatty Arbuckle's "The Butcher Boy." "[Arbuckle] only had to turn me loose in the set and I'd have material in two minutes, because I'd been doing it all my life," Keaton explained (via A Hard Act to Follow).

When it came to his own films, Keaton made sure there was space for on-the-spot creative decisions: "Well as a rule, oh about 50 percent you have in your mind before you start the picture, and the rest you develop as you're making it," Keaton told Studs Turkel. "We never even thought of writing a script, we didn't need to."

Silent film stars often left lots of room for improvisation in their work — in fact, they would often approach a film with only the beginning and end in mind. As far as Keaton and his counterparts were concerned, the path from point A to point B was half of the journey. "When we get the start and the finish, we've got it, because ... the middle we can always take care of. That's easy."

There was no script to follow

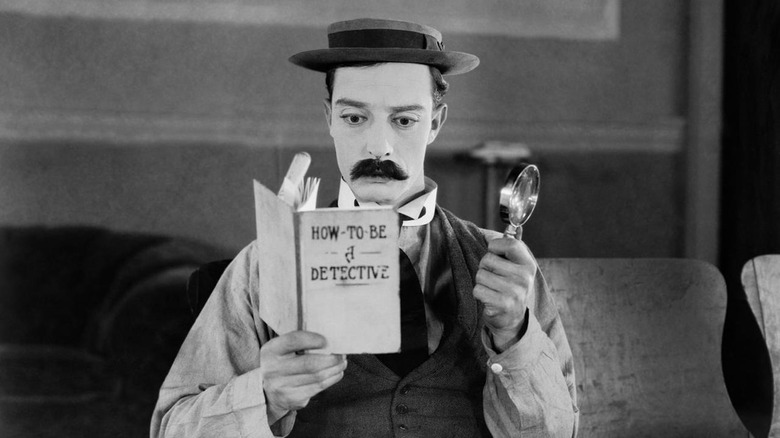

Keaton favored extreme gags over narratives, which is why he chose to make "Sherlock Jr." "I laid out a few of these tricks, some of the tricks I knew from the stage," he recalled (via A Hard Act to Follow). But he realized he couldn't "do it and tell a legitimate story because they're illusions ... it's got to come in a dream." He chose the premise of a projectionist that falls asleep on the job so he could totally suspend reality. Keaton was all about maximizing his creative freedom.

Through creative storytelling, Keaton was able to improvise heavily for many years. Silent cinema left things so open-ended that the Hollywood legend would not even begin to work with a script until "The Cameraman" in 1929. However, when MGM and other studios moved exclusively into talking pictures, cinema changed forever. "New York stage directors, New York writers, dialogue writers, and the musicians union all moved to Hollywood," Keaton recounted to CBC. The new writers brought with them a new style of writing, one that Stone Face described as "joke-happy." "They don't look for the action, they're looking for funny things to say," he lamented.

Keaton and the other kings of physical comedy struggled when silent films fell out of fashion — the film industry had new priorities. Keaton would go on to make several sound films, including the 1931 hit "Sidewalks of New York" (which was actually the actor's most commercially successful film). Still, the actor lost the creative freedom he had enjoyed as a silent film director, including the freedom to improvise.