Contact Could Have Been A Much 'Stranger' Movie

The film world has always been interested in the idea of space travel and extraterrestrials. The first appearance of alien beings occurred in Georges Méliès' 1902 film "A Trip to the Moon," and they've become a staple of science fiction films ever since. Hollywood often portrays aliens as beings we should fear, even Méliès' aliens are vicious, territorial creatures who scare the space-traveling humans off of their planet, so movies that offer intelligent and friendly aliens often catch audiences' attention.

In the 1960s, shows like "Star Trek" showcased a friendly side of extraterrestrials, but popular films like "Alien," and "Invasion of the Body Snatchers" continue to fill the public consciousness with villainous images of alien beings. Even today, films involving slimy extraterrestrials with razor-sharp teeth and wonky skulls can make for a fantastic horror ride, but they are often repetitive and predictable.

In 1997, the Oscar-nominated film "Contact" offered audiences a new kind of alien movie. The Robert Zemeckis movie features an extraterrestrial race but places its main focus on humanity, and our eternal struggle for meaning. Back in the late '90s, "Contact" was a hit with critics and audiences, but modern audiences often find it too bland and introspective for a sci-fi film. This belief intensified when George Miller, who almost directed the movie, revealed the film was "safer and more predictable" than the one he had in mind.

A rough start

According to Vulture's Oral History of "Contact," Carl Sagan and his wife, Ann Druyan, wrote the film's treatment in the early '80s, but it took more than a decade to bring it to theater screens. First, Peter Gruber at Casablanca Record & Filmworks tried to develop the script, but producer Lynda Obst reveals that he ""gave it to all the wrong directors," adding:

"[T]he one I can remember is Robert Harling, a mushy, sentimental rom-com writer and director. Peter changed the hook of the idea. Ann and Carl's hook was a radio astronomer who's looking for signals from other civilizations to see if there's anyone out there. Peter changed it to a woman scientist who had abandoned her son and who goes looking for him — where she should be looking; not at the stars. It was so misogynist it was unbelievable."

Obst left Casablanca but became reattached to "Contact" when Warner Bros. took over in 1989. This time, screenwriter James V. Hart was asked to help with the script, but he was hesitant to take on the project:

"I just kept saying no. It didn't matter how much money they were going to pay me. I thought it was a very difficult adaptation. It wasn't the sort of sci-fi movie that was being made at the time: no aliens, no spaceships, no invasion of Earth."

Most screenwriters weren't sure how to handle an alien movie that didn't include battles, invasions, or abductions. Eventually, after a meeting with Sagan, Hart found the film's story:

"No one had ever talked to Carl — none of the directors that had been onboard ahead of me or the writers. So Lynda designed a weekend where all of our families got together. That weekend, we found the movie inside the book. Mainly, it was around the father-daughter relationship."

Miller's developments

In 1993, a year after finding the movie's premise and further developing the script, "Mad Max" director George Miller joined the project. In the interview with Vulture, Druyan recalled Miller's unique understanding and vision for the film:

"George Miller was the first one that really got that this had to be edgy and not a formulaic big-budget Hollywood product. He had these seminars with experts on military and social movements and about what happens when the world is traumatized, as we imagine the world would be in the case of a first-contact situation ... It was stranger — because that was the idea. The universe is strange."

After going through a few more screenwriters, the story finally found its footing with Michael Goldenberg, who told Vulture that he connected with the film's main character, Ellie Arroway:

"The consistent problem was Ellie as a character — you didn't understand her, so you didn't really empathize or connect with her. But I was that kid, like Carl, who was lonely and read a lot of science fiction and wanted to transcend my mundane circumstances. I saw that in Ellie as a character."

Everyone liked Goldenberg's draft, but Miller felt it needed more development before it was ready to shoot, and the studio disagreed. Druyan recalls the moment "Contact" slipped out of Miller's hands:

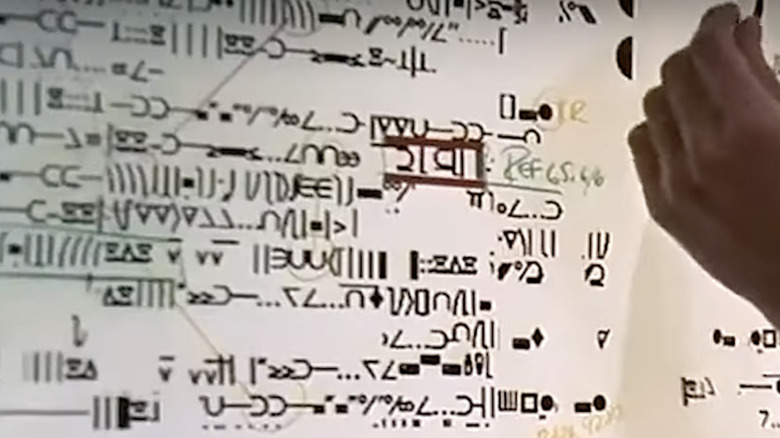

"He came into this meeting with a very complicated diagram about what he wanted to do with the script. They said, 'George, will you commit to shooting this movie by Christmas?' This was the do-or-die moment. We were all praying he would say yes. He said no."

After Miller's departure, "Forrest Gump" director Robert Zemeckis landed the gig and completed the film.

Miller's Interstellar

In a 2015 interview with Collider, Miller admitted he never watched Zemeckis' version of the film, but he read the script. He thought "it basically regressed into a much safer, more predictable thing."

Miller didn't offer many details about his version, but he thinks it would have been similar to "Interstellar," which probably would have blown audiences' minds wide open in the late '90s. Jodie Foster told Vulture that Miller's version took the "super-philosophical, artsy path." Unfortunately, we will never know how that might have translated to the screen. However, just because Miller's idea was stranger, doesn't mean that Zemeckis' version of "Contact" didn't offer audiences something new and interesting.

Not only does "Contact" feature a female scientist, who dedicates her life to her work instead of a marriage or children, the movie also tackles some pretty heavy subjects. Unlike so many popular sci-fi films, "Contact" doesn't exploit aliens for cheap scares and gore. Instead, Zemeckis uses the extraterrestrial contact trope to comment on humanity's endless search for answers about our existence and purpose in the universe.

The main crux of the film is the intersection of science and faith. This is seen throughout the film when Arroway, a staunch atheist, spars with Christian philosopher Palmer Joss (Mathew McConaughey). This conversation reaches its climax when Arroway has a life-altering extraterrestrial encounter that she has no ability to prove.

Zemeckis' risks

While it may be tempting for modern audiences to label Zemeckis' "Contact" bland or predictable, it's important to remember that the film did take risks. It marketed itself as a film about alien contact, but Arroway's meeting with the extraterrestrials lasts less than five minutes, and the extraterrestrial looks totally human, which was bound to disappoint some moviegoers. Additionally, instead of sharing the secrets of the universe or showing off some fancy powers, the extraterrestrial simply explains that humans aren't alone and that Arroway's journey is merely the first step towards true contact with other species. This conversation might seem pretentious or boring to some, but I find this scene far more interesting than one in which the alien merely represents the worst of humanity through its violence and territorialism.

While Hollywood hypes the stranger alien films about bizarre creatures, abductions, and invasions, how many of those films offer a unique experience? Plenty of films can offer cool special effects or interesting creatures, but "Contact" asks questions that will interest humanity for many years to come.