Dr. Strangelove's Release Led To A Scrap Between Stanley Kubrick And Studio Execs

Stanley Kubrick's 1964 satire "Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb" is now regarded as an American classic, one of a legendary filmmaker's strongest films. The film's comedic treatment of a hot-button global issue was as revolutionary as it was hilarious. Still, the risky subject matter gave the film's production company pause, leading to pushback from the executives over at Columbia Pictures.

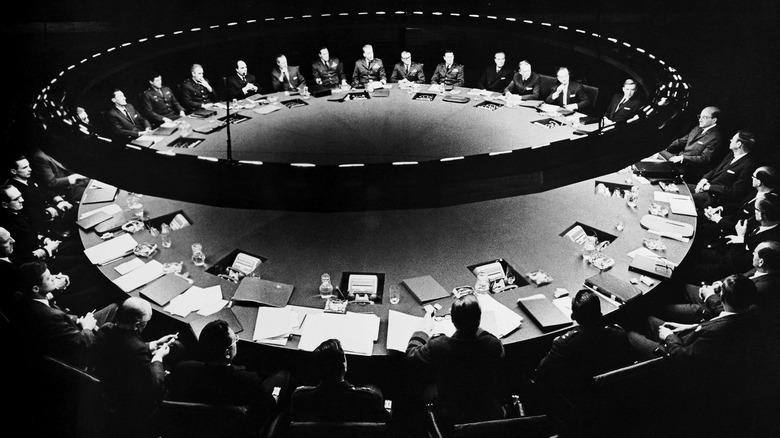

"Dr. Strangelove" centers around a worst-case Cold War scenario: what if a loose cannon in the U.S. military triggered a nuclear attack against the Soviet Union? A hodge-podge group of high-ranking personnel must scramble to pick up the pieces, three of whom are played by Peter Sellers.

The comedy was originally written as a conventional narrative drama, producer James B. Harris revealed in a behind-the scenes documentary (via Toby Roby). Harris worked closely with Kubrick while writing "Dr. Strangelove." The director told Harris that the story of nuclear disaster would be "much better told in the form of a satire, of a comedy, than it is in the straight story that we developed," the producer recalled.

Kubrick had been intrigued by the atomic bomb for quite some time. He felt that nuclear disaster lent itself perfectly to comedy because every scenario involving hydrogen bombs "lead to very paradoxical outcomes," he explained in a rare interview included on the Criterion release of the film (via Science and Film). In Kubrick's words, "the most thematically obvious thing about 'Dr. Strangelove' was the paradoxical outcome of any particular line of thought."

This satirical treatment of a grave subject matter was embraced by his creative partners, but it got him into hot water at Columbia.

or: How Columbia Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Film

While "Dr. Strangelove" was in production, the studio started to distance itself from the project. Kubrick confronted producer Mo Rothman about not showing his face on set in a heated phone call, co-writer Terry Southern claimed in his essay "Notes from the War Room." Rothman told the director that he was busy with another project that was "not so zany" as "Strangelove."

Kubrick attempted to mend the relationship with Rothman by buying him a high-end golf cart, but to no avail: the producer refused to accept the gift. "He said it would be 'bad form,'" Kubrick told Southern. "'Bad form!'" the director exclaimed. "Can you imagine Mo Rothman saying that? His secretary must have taught him that phrase!"

The legendary filmmaker also butted heads with Columbia's publicity department who, according to Rothman, were "having a hard time getting a handle on how to promote a comedy about the destruction of the planet." The same department would later attempt to distance Columbia from "Dr. Strangelove" by describing the film as "a zany novelty flick which did not reflect the views of the corporation in any way." The production company would change their tune years later when the Library of Congress selected "Dr. Strangelove" as one of the fifty greatest American films of all time — "in a ceremony at which I noted Rothman in prominent attendance," Southern remarked.

It may have taken some time, but luckily for us, Columbia learned to stop worrying and love the film.