Citizen Kane Wasn't Always Seen As A Cinematic Classic

In the annals of movie history, few titles hold as much weight as "Citizen Kane," which has become shorthand for the Great American Film, like the Great American Novel, and is frequently shortlisted as such. It's not just the American Film Institute that thinks "Citizen Kane" is the best movie ever made. Once every 10 years, the British Film Institute's Sight and Sound magazine compiles its own renowned list of the 100 greatest movies of all time based on an international poll of critics, and from 1962 to 2012, when Alfred Hitchcock's "Vertigo" finally edged it out of the top spot, "Citizen Kane" reigned supreme.

However, when producer, director, star, and credited co-writer Orson Welles first sprang his masterwork on the moviegoing public in 1941, it was not met with the same open arms. Reviews were good — better than the ones other misunderstood classics like "Apocalypse Now" initially received — and the film did score nine Academy Award nominations. Yet it was booed at the Oscars and only won for Best Original Screenplay, a credit Welles shared with Herman Mankiewicz (who disputed Welles' co-authorship).

For this and other reasons, "Citizen Kane" was, as History.com notes, rather controversial in its day. Radio City Music Hall — the go-to premiere spot for RKO Pictures, the film's production and distribution company — even backed off on rolling out the red carpet for it. Much of the controversy was inflamed by the parallels between protagonist Charles Foster Kane and real-life media tycoon William Randolph Hearst, who leveraged his power against the film and almost kept it from theaters. When "Citizen Kane" finally did open on September 5, 1941, it was a box-office failure and soon found itself gathering dust in the RKO archives, much like the huge trove of discarded possessions Kane leaves after his death.

'Every shot has an idea'

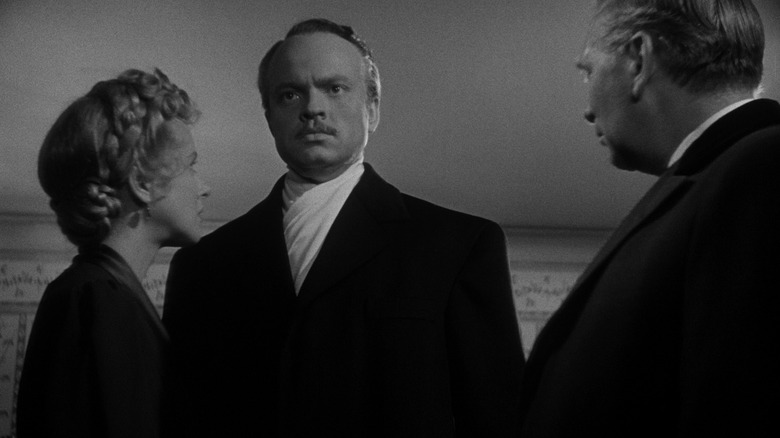

It was not until it was rereleased and reappraised in the 1950s that "Citizen Kane" came to be regarded as the classic it is today, thanks in part to Gregg Toland's cinematography, which made unconventional use of techniques like low-angle shots and deep focus. Orson Welles broke from cinema tradition and had sets constructed with ceilings to allow for those shots. From a smashed snow globe to a burning sled, he and Toland conceived a series of indelible images that would go on to influence numerous filmmakers, including Martin Scorsese, who noted how "Kane" opened up a new frontier for camera positioning, and Steven Spielberg, who praised the "audacity" of Welles' approach.

By his own admission, Kane doesn't know how to run a newspaper; he just tries "everything he can think of," and the same could be said of Welles as a first-time filmmaker. As Sidney Pollack observed: "Every shot [in 'Citizen Kane'] has an idea. There's a concept being executed at every second." The film also heralded a new narrative style whereby the meaning of Kane's life and his final word, "Rosebud" (a secret the audience alone is privy to), comes together piecemeal through flashbacks, newsreels, and multiple perspectives, as opposed to the standard omniscient third-person point of view.

Although Hearst made a concerted effort to bury the film, and succeeded in the short term, "Citizen Kane" eventually found its audience, leaving it vindicated by time. It continued to attract controversy, however, with the publication of Pauline Kael's 1971 New Yorker essay "Raising Kane," which renewed debate over the question of the film's true authorship. In 2020, Gary Oldman, Charles Dance, and Tom Burke portrayed Mankiewicz, Hearst, and Welles, respectively, in David Fincher's Oscar-nominated biopic, "Mank," and by then, "Citizen Kane" was well-established as a classic.