12 Best Performances In Steven Spielberg Movies

Steven Spielberg is renowned first and foremost for his uncanny skill as a visual storyteller. In this regard, he belongs in the cinematic firmament alongside John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, and not many others. But we rarely talk about Spielberg's facility as a director of actors, which is bizarre given that he's made some of the greatest, most widely viewed movies in the history of the medium.

What gives? Good question. There have been nominations aplenty, but it wasn't until 2012 that an actor (Daniel Day-Lewis in "Lincoln") won an Oscar for a performance in a Spielberg film. Mark Rylance's Best Supporting Actor win for "Bridge of Spies" in 2015 is the only other victory. These were undeniably great turns, but how is it possible that the most influential filmmaker of the last 50 years has gone relatively unheralded when it comes to directing actors?

It's certainly not due to a dearth of excellence. In crafting the films that fired our imaginations, Spielberg brought together amazing actors and occasionally coaxed career-defining portrayals from them. There's a load of brilliance to choose from, but these 12 performances stand out as Spielberg's finest collaborations.

Henry Thomas - E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

Henry Thomas turned 10 on the second day of principal photography for "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial." He wasn't the first unusually young actor asked to anchor a major motion picture, but it's hard to think of a film so wholly reliant on an adolescent's versatility to sell their artificial costar. Carlo Rambaldi crafted a movingly lifelike creature, but his alien would've fallen flat without Thomas' inspired feat of make-believe.

Most of the best actors working today will tell you their success and longevity depends on their sense of play. If they can't turn up on set and access the childlike wonder that drove them into the profession, their career is likely nearing an end. Meanwhile, kids raised in a relatively privileged environment know nothing but play. When they retreat into their bedrooms (if they're fortunate enough to have one to themselves), they create fantastic worlds governed by a quicksilver logic. That scene where Thomas guides E.T. through his room is without question the gold standard when it comes to depicting this feverish state of mind. Although Thomas' Elliott has two siblings, he doesn't appear to have any close friends, so he's overjoyed to articulate the law of his land to E.T. We've all been Elliott to some degree, but has an actor of Thomas' age ever accessed that feeling of loneliness with such casual exactitude? There have been more accomplished child performances (Tatum O'Neal in "Paper Moon" is as good as it gets), but this is uncanny, unaffected stuff. Thomas is the movie.

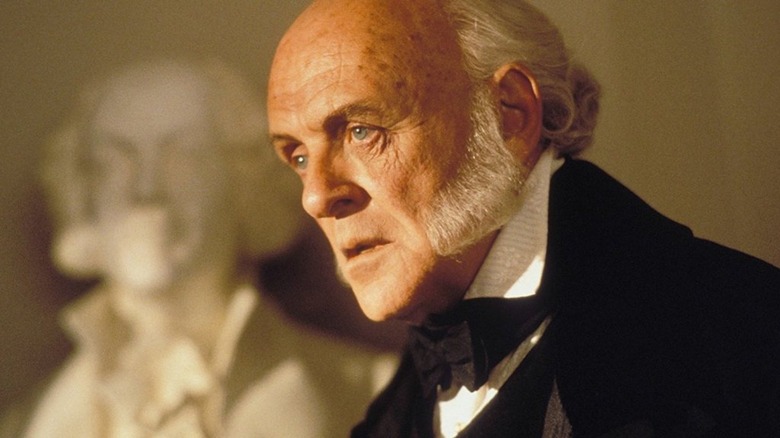

Anthony Hopkins - Amistad

"Amistad" is an odd movie. The opening mutiny is a dynamic feat of visual storytelling, but Spielberg's casting instincts failed him with Matthew McConaughey. Or maybe David Franzoni's screenplay failed to provide him with a character worthy of McConaughey. In any event, there's a massive hole in "Amistad" where a compelling protagonist would typically reside.

"Amistad" generally plays like a dry run for "Lincoln." It's about good, intelligent men arguing for the equal treatment of enslaved people under the principles established by the United States' founding fathers. Anthony Hopkins' John Quincy Adams lingers on the edges of "Amistad" until the climax, where he steps forward to shame the Supreme Court into ruling in favor of the African mutineers who righteously murdered their slavers in the hopes of returning to their homeland. He is handed an 11-minute speech, and it is glorious. "Amistad" is well on its way to being a misfire until this sequence. But Hopkins, buried under prosthetics and mimicking the creaky movements of a septuagenarian, soars above this artificiality and brings it home. "Give us the courage to do what is right. And if it means civil war? Then let it come. And when it does, may it be, finally, the last battle of the American Revolution."

Mike Faist - West Side Story

Any actor who knows their stuff will correctly tell you Mercutio is the role in "Romeo and Juliet." That's Riff in Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim's "West Side Story," and while I've nothing but tremendous affection for Russ Tamblyn's performance in Robert Wise's 1961 big-screen adaptation, what Mike Faist does with the character in Spielberg's 2021 rendition is nothing short of transcendent. His Riff is famished for conflict. He's wild, wiry, and sexy as hell. As should always be the case in a production that originates from "Romeo and Juliet," there is genuine erotic heat between Riff and Tony (Ansel Elgort). Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner get this and create the perfect conditions for a scene-stealing turn. Faist brings the fire.

In Spielberg's film, Riff has obtained a gun and intends to use it in the Jets' looming rumble with the Sharks. Tony must convince Riff to surrender the gun, which results in a masterfully choreographed game of keep-away. Faist has completely dominated the film up until this point, to the extent that he is essentially serving the role of the protagonist. Elgort's Tony is the more sympathetic of the two, but we can't keep our eyes off Faist. He propels the film right up to the moment he's stabbed. And then, in a beautiful bit of transference, he hands the movie over to Elgort. We knew going in that Riff was not long for "West Side Story," but we've never mourned the character's death more palpably than we did here.

Goldie Hawn - The Sugarland Express

The breakout star of "Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In" had already proven she was more than just an effervescent goofball by winning an Oscar in 1970 for her supporting turn in Gene Saks' "Cactus Flower," but this is the better performance by far. Goldie Hawn's Lou Jean Poplin is a marvelous creation, a fiercely protective mama bear who goads her dopey convict husband, Clovis (William Atherton), into escaping from a Texas prison (even though he has a mere four months left in his sentence) so they can keep their son from being placed in the care of a foster family. Their plan goes from misguided to outright disaster when they take a patrolman (Michael Sacks) hostage, thus touching off a statewide car chase that is doomed to end in incarceration, if not death.

The screenplay by Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins gives Hawn plenty of opportunity to indulge her gift for playing stupid, but Spielberg never once allows us to look down on Lou Jean. Has she done a remarkably dumb thing? Absolutely. But Hawn finds inventive, childlike layers to this young woman who justifiably doesn't trust the system to give her a fair shake, much less return her child. Whether she's forming a bond with their shockingly calm captive or getting a kick out of a Wile E. Coyote-Road Runner cartoon at a drive-in, Hawn brilliantly communicates the impulsive inner life of this ultimately tragic fool.

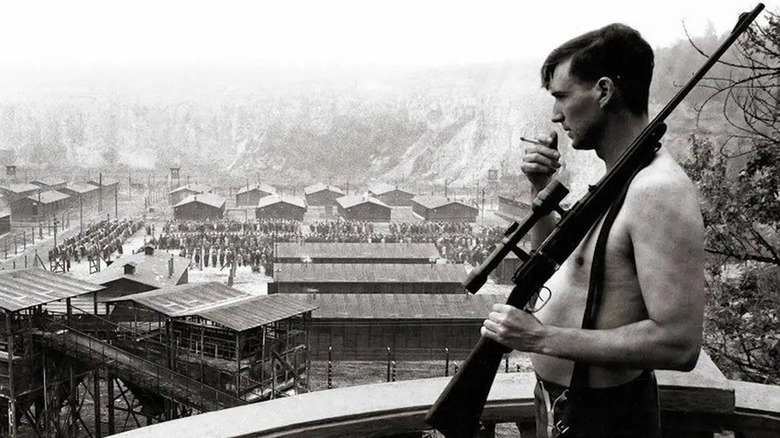

Ralph Fiennes - Schindler's List

SS-Untersturmführer Amon Goeth is the pathetic apotheosis of the Nazis, an uneducated slob taking out his mindless rage on an entire ethnicity because a failed artist told him they were responsible for his country's defeat in World War I. He has no discernible talent. He is simply a stupid man capable of shocking cruelty, like idly sniping the internees at the Polish concentration camp he oversees. The audience has no interest in empathizing with such a character, which leaves Ralph Fiennes, in his first major Hollywood role, the unenviable task of locating what's left of Goeth's decayed humanity. He finds it by leaning into the character's childishness.

Fiennes' Goeth thrives on the fear of his underlings, but prefers the isolation of his shoddily kept quarters. He is a man of no true importance to the party, so he wastes away the day guzzling rotgut, while coercing his Jewish maid (Embeth Davidtz) into a sexual relationship. Fiennes literally embodies the "master race" stereotype via his booze-distended belly, but, in his scenes with Davidtz, he comes off as a fumbling schoolboy desperate to impress his crush (before flying into a violent rage). This is the tragedy of men like Goeth. They are the sum total of their resentments. Fiennes could've played Goeth as an imperious beast, but he lets us see the gears grind in this dope's thought process. In doing so, he reveals a mediocrity who, when given even the slightest bit of power, could never be anything but a monster.

Tom Hanks - Saving Private Ryan

Never undervalue the presence of a true movie star. I thought long and hard about which of the Toms to include on this list, but there is not another actor on the face of the planet who could've calmed moviegoers in the wake of the ferocious Omaha Beach sequence that kicks off "Saving Private Ryan" as swiftly as Tom Hanks. I also can't think of another actor who could've kept audiences from fleeing for the exits at the height of this bravura sequence's mayhem. Hanks has often been referred to as the Baby Boomer Jimmy Stewart. This is where he earned it.

His utility throughout the rest of the movie is barely that of a leading man. It's an ensemble film, and Hanks follows his character's lead by disappearing into the background whenever he can. He doesn't want his men to know what he did before the war because it's not germane to the efficacy of his leadership. His tightest bond is with Tom Sizemore's Sergeant Horvath, who isn't much intellectually, but he's unswervingly loyal and trustworthy. Miller might be a school teacher, and maybe those organizational instincts have served him well in this conflict, but it's his innate quality of being that matters. Hanks doesn't have to be much more than Hanks in this situation, but that quality has never been essential.

Mark Rylance - Bridge of Spies

"The boss isn't always right, but he's always the boss." One of Spielberg's most nuanced films hinges on a preternaturally calm performance from British stage great Mark Rylance, who plays Rudolf Abel, a Russian spy being proffered in exchange for a U.S. military pilot who failed to ingest cyanide upon being shot down over Soviet airspace. This contrast in styles is what makes the film so absorbing. Rylance's character accepts his circumstances. This is the risk of serving as a spy in a foreign country. When he's hooked up with insurance lawyer James Donovan (Tom Hanks), who is expected to do the bare minimum, he's already assumed the worst. He didn't count on his counsel giving a damn.

While the American pilot is tortured, Abel is afforded reasonable comfort. Rylance never betrays a hint of fear until the end, when we realize the prisoner swap is possibly the worst outcome for Abel. Shouldn't he panic? "Would it help?" This is a fine coda to "Lincoln" and "Amistad": films that argue for the humane and just ideals on which the United States was founded. Spielberg doesn't do disillusionment. He points to the real-life stress tests on our democracy, and emits a low-key hurrah that we rose to the challenge. If Rylance, playing a character determined to undermine the United States, can serenely trust our legal system, why can't we?

Whoopi Goldberg - The Color Purple

"You sho' is ugly." The constant indignities suffered by Celie in Spielberg's adaptation of Alice Walker's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel were always going to land like haymakers, but Whoopi Goldberg, a New York City theater sensation making her acquaintance with the whole wide world, absorbs them with heartbreaking disappointment, as if, this time, she felt everything would play differently for once. Everything has been taken from Celie: her freedom, her children, her ability to have children. She has no recourse. But she must live this life, and, in Goldberg's hands, she does so with a quiet grace.

Shug (Margaret Avery), the woman who delivers that "ugly" insult, winds up being Celie's protector and inciter. Watching Goldberg gradually brighten in her presence is a tear-jerking joy primarily because her Celie makes us believe that, no matter how hopeless her situation gets, her day will come. Celie is a rare female protagonist in Spielberg's oeuvre, which is strange and disappointing in equal measure, and her experience is, obviously, utterly foreign to the filmmaker. But there is a powerful alchemy between the two artists, one that seems derived from an undying belief in hope. Spielberg received criticism for his cautious treatment of Walker's novel (most notably omitting the lesbian relationship between Celie and Shug), but he has never been more simpatico with a leading actor. Now that we're well acquainted with Goldberg as, first and foremost, a comedic dynamo, her painfully shy portrayal of Celie has only grown more powerful.

Richard Dreyfuss - Close Encounters of the Third Kind

Spielberg swung for the fences during the casting phase of "Close Encounters of the Third Kind." He wanted a big-screen icon for Roy Neary. He hit up Dustin Hoffman, Gene Hackman, Al Pacino, and James Caan. He nearly snagged taciturn sex symbol Steve McQueen for the part, but the star, who evidently loved the script, couldn't cry on cue.

Spielberg had directed Richard Dreyfuss to stardom on "Jaws," but he wasn't the Roy Neary he'd initially imagined. Aside from Hoffman, it's highly unlikely Dreyfuss ever competed with the other aforementioned actors for a part prior to "Close Encounters" (though I'd love to watch a readthrough of "The Getaway" with Dreyfuss as Doc). But Dreyfuss kept the pressure on, and Spielberg finally relented. It's a wildly unsympathetic role. Neary jilts his family and books a trip to the interstellar unknown. Spielberg was a bachelor when he made the film in the late 1970s, and still smarting from the breakup of his own family, which might be why he imagined Neary's home life as a cacophonous hell of shrieking, "Pinocchio"-hating children, and a wife who balks at his treatment of mashed potatoes. There's not a whole lot on the page, which requires Dreyfuss to get us on Neary's brood-abandoning wavelength. It works! When he volunteers to venture off into the stars, you're happy for him. That he failed as a father is ultimately irrelevant. To hell with Goofy Golf.

Christian Bale - Empire of the Sun

At the outset of Steven Spielberg's World War II masterpiece, Jamie Graham is a spoiled brat, an only child of wealthy British expats living the high life in Shanghai. He's taken near-permanent residence in his hyperactive imagination, imagining the kinds of wild aerial dogfights you only see in movies. The kid's got planes on the brain. Then the Japanese wade in. Jamie is separated from his family and spends the next four years of his life in an internment camp. By war's end, he is no longer Jamie. He is Jim.

Thirteen-year-old Christian Bale was just beginning his transition into manhood when he landed this role, and he is perfectly devoid of actorly sophistication. Jim is a capable lad, which earns him the admiration of inveterate scavenger Basie (John Malkovich), but he still lives in his dreams. Bale projects both rare intelligence and an enthusiasm that borders on religious fervor. During the U.S. Army's raid on the Japanese runway adjacent to the camp, he places himself in grave danger as he fanboys out over a detachment of P-51 fighters ("Cadillac of the Sky!"). Later, he is inspired by the brilliantly lethal light emanating from the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki to revive the quite dead Mrs. Victor (Miranda Richardson). Bale hurls himself into the scenes with the recklessness of a born dreamer. His Jamie/Jim is alternately exhilarating and exhausting. He's a deranged Elliot, and maybe the truest representation of Spielberg's unceasingly hopeful interior life.

Daniel Day-Lewis - Lincoln

It's that high, honking voice. No one expected the Great Emancipator to sound like such a dork, but Daniel Day-Lewis believed that, given where the president was from and how most great orators were read rather than heard in the pre-radio era, Lincoln's tone might reside in a higher register. It's not the most aesthetically pleasing choice, but his full commitment sells us on the idea. Just take a look at the man. Why wouldn't the tall, slender Lincoln speak with a bit of a squeak?

That Spielberg, who tends to work quickly, could collaborate so easily with a method actor is a testament to the director's malleability. He usually works with movie stars like Tom Hanks, Harrison Ford, and Tom Cruise: highly disciplined artists who come in prepared to make days. When he's strayed outside of this comfort zone in the past, it hasn't always gone well for him (e.g. he had a rough go with Dustin Hoffman and Julia Roberts on the ghastly "Hook"). Perhaps that's why Spielberg took a three-year break between "Lincoln" and "Bridge of Spies." Regardless, Day-Lewis yet again disappeared into a role, and Spielberg turned out a stirringly intelligent depiction of how the legislative sausage gets made.

Roy Scheider - Jaws

Robert Shaw and Richard Dreyfuss get the showiest moments in Spielberg's groundbreaking horror-adventure, but Roy Scheider, a character actor who'd been bucking for stardom, is the glue that holds the Orca together. Given that I watched this movie almost every day for a few years during my adolescence, Scheider's Chief Brody has always been something of a surrogate father to me. He's a good man who expects to do nothing more than keep the peace between quarrelsome vacation-town neighbors; then a rogue great white shark takes up residence off the coast of his island, and the ocean-hating officer is forced to take to the water to slay the seemingly insatiable beast.

Spielberg is in off-handed, overlapping dialogue mode here, and while we know he was miserable during a good chunk of principal photography, every single actor seems to be having a ball. Scheider has to do a good deal of darting about within the frame, which was probably more labor-intensive than it looks (especially with a director fretting that he might get fired). Nevertheless, he nails every scene. Whether he's spilling a container of paint brushes, bantering with his overwhelmed deputy ("Let Polly do the printing"), or playing an impromptu game of follow-the-leader with his son, he is always relatable and unfailingly decent. Spielberg has spent most of his career working through his daddy issues, which makes Scheider's Brody an anomaly. He's the greatest big-screen dad this side of Atticus Finch.