The Wachowskis Wanted The Matrix Trilogy To Change The Way We Watch Movies

Say what you will about the Wachowskis, but you can never accuse them of being timid. From "The Matrix" films to their groundbreaking TV series "Sense8," these are two filmmakers who've always stuck to their visions and created art on their own terms. Nothing they've created has been as universally beloved as first "Matrix" film, but that's because that was the last time in their careers where they've needed to cater to general audience expectations. Everything since then has been a little less accessible and a little more niche, but it's all been undeniably unique and ambitious.

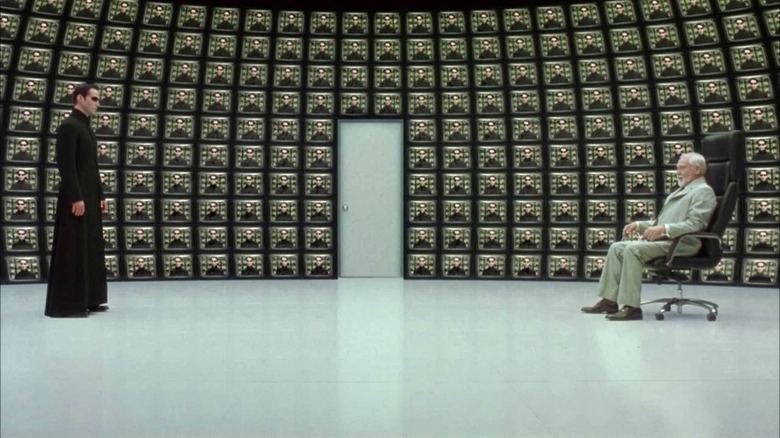

"Matrix: Reloaded" and "Matrix: Revolutions" are no exceptions. They're both bold, innovative stories that challenged the expectations of a lot of fans of the original. The first movie had a simple plot with crowd-pleasing themes, but "Reloaded" complicated all of that every chance it had. As Lana Wachowski put it in a 2012 interview: "The first movie is sort of classical in its approach, the second movie is deconstructionist and an assault on all the things you thought to be true in the first movie." The first sequel was notably received a lot less positively than the original, which the Wachowskis seemed to anticipate. After all, everything about Neo's self-discovery and his role as The One was re-examined and put into question, and this wasn't resolved by the end of the film.

The third movie, "Revolutions," was described by Lana as the most ambiguous: "It asks you to actually participate in the construction of meaning." The movie was criticized at the time for being confusing in its plot resolution, but that was because they wanted the audience to come to their own conclusions on what exactly happened.

Letting the audience participate

It was this creative impulse that later led the Wachowskis to adapt David Mitchell's novel "Cloud Atlas" in 2012. "It did something similar," Lana said. "You read the book and there's connections that were only available if you brought your agency to the book."

The book and the film both require the audience to fill in some gaps, to read between the lines much more so than your typical blockbuster. This is exactly what the filmmakers were trying to do with "Revolutions" in particular: change the role mass audiences take when watching an action movie. Don't just give them the answers; make them work for it, make them come to their own conclusions.

"Audiences go to the movies to turn off," Lilly Wachowski said in the same interview, "And we don't want to turn off when we go to the movies. We don't want a passive moviegoing experience ... we want to participate." Both Wachowskis believed that movies like this were becoming increasingly less common in the mainstream film industry. "We don't want the thing that we love about cinema to continue to contract and shrink, which is sort of where it's heading," Lana said.

Movies are matrixes

The Matrix is often interpreted as a metaphor for capitalism or the trans experience or a ton of other real-life things. None of those interpretations are necessarily wrong, but the Wachowskis often looked at it as a metaphor for movies themselves. As Lana put it, "Movies are things you go inside, and they are immersive, and you are cocooned by them, and they tell you what to see, what to think, what to feel."

Neo may escape the Matrix about a third of the way through the first movie, but the film itself doesn't escape its parallels to the Matrix. It sticks to the conventional three-act structure and its themes are simple and vague enough that anyone can interpret it in any way they want. It's why the alt-right was able to adopt the concept of the red pill despite the Wachowskis' obvious left-wing politics. The film is far more thoughtful than the average blockbuster, but it's still a story with a straightforward narrative and a conclusion that won't make anyone uncomfortable.

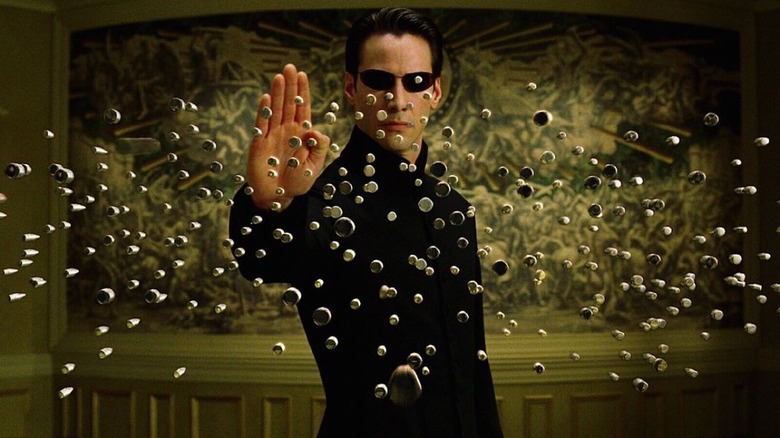

The goal with the rest of the trilogy was to do to the audience what the first movie did to Neo. Whereas the second act of "The Matrix" rips Neo away from the comfort of his previous reality, the second movie of the trilogy rips us away from the easy chosen one narrative of the original. The third act of "The Matrix" has Neo taking agency in his life for the first time, learning to find his own meaning in a cold, crazy world. As Lana put it, Neo was forced to "participate in the construction of meaning to his life," and that's exactly what the audience was forced to do throughout "Revolutions."

An audacious trilogy

"What we were trying to achieve with the story overall was a shift, the same kind of shift that happens for Neo, that Neo goes from being in this sort of cocooned and programmed world, to having to participate in the construction of meaning to his life," Lana explained. Whether they succeed or not is up for debate, but you've got to respect the ambition either way.

It wasn't the only way they tried to change the way we watched movies, either. The first two sequels were also unique in that they were intended more as one massive film than two complete parts. The Wachowskis initially wanted the two movies to be released within two to three months of each other, and eventually settled for a six-month gap, which was still unusually close together. They also released a ton of supplementary material around the films like The Animatrix series, which provided extra context to stuff that happened in the sequels.

Everything about the production of these movies was far more high-effort than what anyone could've expected at the time. But looking back at it with what we know about the Wachowskis vast array of ambitious projects, it makes perfect sense.