The Secrets Behind The Alien Language In Arrival

Are humans alone in the universe? Numerous sci-fi and horror stories have attempted to answer that question, and the truth is still anyone's guess. Some imagine aliens exploding out of human chest cavities, while others prefer to think of them as lost explorers with an addiction to Reese's Pieces. Either way, the potential existence of extraterrestrials has been a topic of conversation among humans since cave painting days, and it persists today.

Today, instead of finger painting strange figures on rocks with natural pigments, people write aliens into scripts and watch movies about them. In those movies, filmmakers imagine how creatures from other planets might look, sound, and most importantly, how they might communicate. Steven Spielberg's aliens prefer music and have lightbulb fingers, while James Cameron invented a whole new language for his alien characters. Of course, there's no way for mere humans to know which Hollywood take is most accurate, but there are some ideas about extraterrestrials that are more intriguing than others.

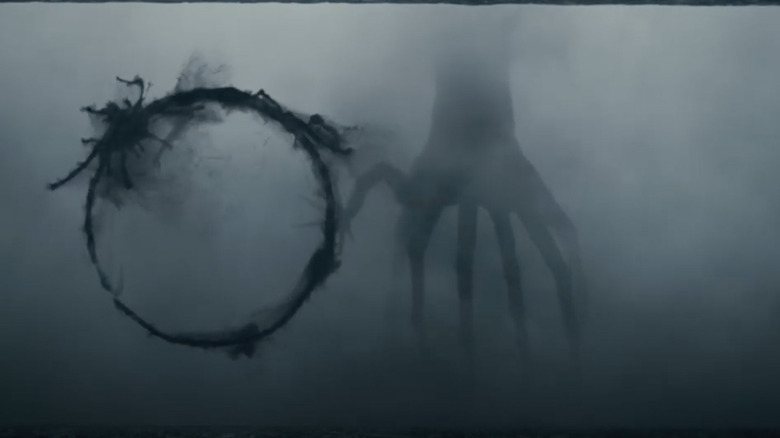

2016's "Arrival" features aliens known as Heptapods who communicate by secreting intricate, inky circles that are later translated into various human language. Watching the dark wisps of ink arrange themselves into obscure shapes is captivating, cinematic, and in fact, scientific. In an interview with Space, the film's production designer, Patrice Vermette, discusses how real-world linguists and archeologists assisted in the creation of the Heptapod language.

Circles

When a squadron of alien ships arrives on Earth, the linguist Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams) is recruited by the American government to help communicate with some of the extraterrestrials. Along with mathematician Ian Donnelly (Jeremy Renner), Banks unravels the mysterious alien language and earns the ability to see time in a non-linear way. Turns out, everyone's favorite Doctor is correct: time isn't a straight line, it's "a big ball of wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey stuff."

With this in mind, the film's director, Denis Villeneuve, wanted the Heptapods' language to be based on circles, which was a challenge to Vermette. He told Space about the struggles he had making such a familiar shape interesting to audiences, saying, "We wanted to have something that was aesthetically pleasing, and that [viewers] could not at first know that it's a language or not [sic]."

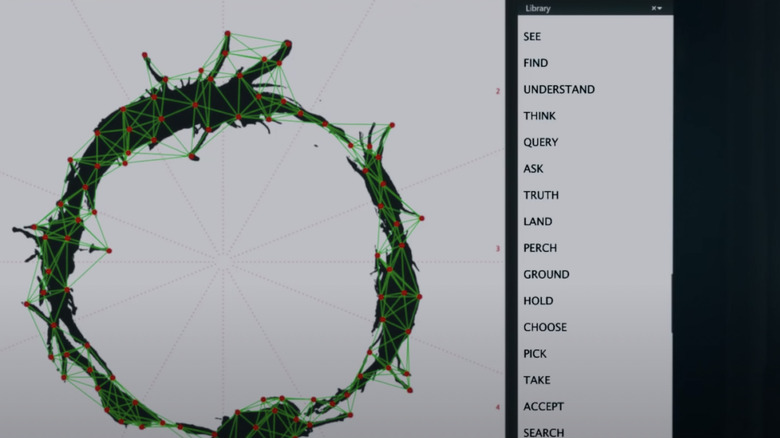

Vermette struggled for a while before his wife, artist Martine Bertrand, offered to help. A few days later, she showed her husband a version of the tendrilled circles you see in the film, and the beginnings of an alien language were born. Vermette and Bertrand researched existing languages and created 100 variations of the tendrilled circle. Vermette told Insider, "We looked into ancient Asian language, Arabic language, tribes from Northern Africa. It's [all] part of our history." Vermette and Bertrand call the splotchy circles logograms, which, depending on their complexity, can communicate a word or an entire sentence:

"The difference lies in the complexity of the shape. A logogram's weight carries meaning, too: A thicker swirl of ink can indicate a sense of urgency; a thinner one suggests a quiet tone. A small hook attached to one symbol makes it a question. The system allows each logogram to express a bundle of ideas without adhering to any traditional rules of syntax or sequence."

Translation

Once Vermette and Bertrand created the alien language, they had to figure out how the characters in the film would translate it. To help with this process, they brought in Stephen Wolfram, founder of Mathematica coding software, and his son Christopher — they attempted to translate the tendrilled circles in the same way they would any other unknown language. They looked for patterns.

In linguistics, patterns are known as redundancies, and they are present in all languages. Even the sounds of dolphins and ants have patterns, and these connections can be used for translation. The Wolframs broke the logograms into 12 pieces and input the data into a program which detected patterns within the symbols. Once the Wolframs confirmed these redundancies existed, linguist Jessica Coon helped give them meaning.

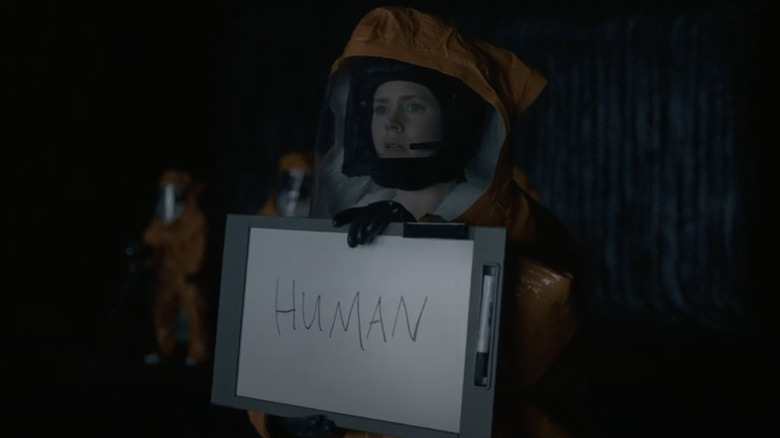

"They brought me to the military cryptography tent," Coon recalled, "and wanted to know what's going to be on the white boards [sic] here where they're deciphering the language, what's their to-do list look like? How would somebody annotate these logograms? So they sent me a stack of these logogram printouts and said, well, you're a linguist, figure it out." Building on the Wolfram's work, Coon analyzed the patterns of the language in an attempt to understand the Heptapod's grammar:

"The way a linguist would approach this is the same way a linguist would approach understanding the grammar of a human language, which is looking for patterns. In the movie, one of the scenes they show is Ian walking and they're trying to get the Heptapod equivalent of 'Ian walks' or 'Ian is walking.' Then maybe they would ask for 'Louise is walking' and look at these two symbols and say what do they have in common?"

Communication

Amy Adams' Dr. Louise Banks uses these real-world linguistics techniques to translate the Heptapod language in "Arrival." Once she does, she earns the ability to see time in a non-linear way. Anyone looking to dissect the inky circles to gain this ability is going to be disappointed. The film's language isn't real, nor is precognition – as far as we know.

While the film can be categorized as an alien movie, its underlying message is much more complex. The movie focuses on humanity's struggle to communicate with extraterrestrials, but its main message centers on how we communicate with each other. The film is replete with depressing examples of just how much humanity sucks at understanding each other. A world war almost breaks out because of communication breakdowns, but "Arrival" offers some important lessons to learn from.

Better communication can always be achieved by simply taking the time to find common patterns and understand each other.