Glory Didn't Cut Any Corners When It Came To Authenticity

Culturally speaking, Edward Zwick's Civil War drama "Glory" did not hit theaters at the most opportune moment. An ambitious account of the then little-known 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the Union Army's second African-American regiment, critics approached it with dread. Here, in the wake of Richard Attenborough's "Cry Freedom" and Alan Parker's "Mississippi Burning," was yet another vital chapter of Black history being told not only by a white filmmaker and a white screenwriter (Kevin Jarre), but from the perspective of a white character (in this case, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, played by Matthew Broderick). Arriving six months after the release of Spike Lee's incendiary "Do the Right Thing," it was, on paper, an unwelcome reminder of how far Hollywood had to go in terms of behind-the-camera representation.

Zwick's margin of error was non-existent. He could do nothing about the framing of Jarre's narrative, which was inspired by a monument in Boston Common dedicated to Shaw and the 54th that he used to pass by during his undergraduate studies at Harvard. Much was known about Shaw, but aside from the heroism of William Harvey Carney, there was little in the historical record about the individual soldiers. Zwick had to know he'd be in the crosshairs, particularly since he was best known for his Yuppie-catering network drama "thirtysomething" and the romantic comedy "About Last Night..." (a heavily sanitized adaptation of David Mamet's stage play, "Sexual Perversity in Chicago"). Now he was attempting to catapult himself into the upper echelon of studio filmmakers. To do so, he'd need to win over a lot of critics who viewed television directors with extreme skepticism, if not outright antipathy. He had to ace this assignment.

Capturing the fine details of a bloody war

Shot over two-and-half months in early 1989 on a modest (given the film's scope) $18 million budget, "Glory" was exacting in its period detail. According to The New York Times, the production required the manufacture of 200 replicas of 1851 Enfield rifles, hundreds of Union and Confederate uniforms, 150 cavalry mounts, and 50 artillery pieces. There were farm animals. Lots of farm animals. This is typical for a studio-financed period film. But Zwick took his meticulousness to a Kubrickian level by placing silver candlesticks owned by the real Colonel Shaw in a single shot of the film. He also employed Civil War reenactors, who, according to the director, were "wonderfully committed to historical accuracy to the point of madness."

Most importantly, Zwick sought the expertise of Civil War historian Shelby Foote, who advocated for verisimilitude wherever possible, particularly in the writing of the dialogue. There was to be no anachronistic speech, no modern slang. Such adherence to verisimilitude can trip up lesser actors, who retreat into a presentational form of acting (akin to high school kids adopting shoddy British accents when performing Shakespeare), but Zwick hadn't cast slouches. Indeed, Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman, and Andre Braugher had no difficulty delivering the era-specific dialect like they were born in the 1800s, but they were concerned about depiction. Washington, who'd played anti-Apartheid activist Steve Biko in the white-savior epic "Cry Freedom," broached this issue with Zwick. They were heard. Loud and crystal clear. ”Everyone had input into their characters,” said the director. "So many of their contributions found their way into the film."

From Ferris Bueller to Colonel Shaw

To be a truly authentic depiction of the 54th regiment, however, Zwick had to capture the awkward, occasionally adversarial dynamic between Shaw and his soldiers. As the protagonist of "Glory", the abolitionist colonel had to journey from schoolroom idealist to effective leader of these oppressed men for whom he was willing to give his life. Three years removed from playing the epitome of white privilege in "Ferris Bueller's Day Off," it seemed that Broderick was either going to be John Wayne-as-Ghengis-Khan-level miscasting or a counterintuitive masterstroke à la Marlon Brando as Don Corleone. Ultimately, it was neither. Broderick is initially off-putting as Shaw, as he should be. A shell-shocked survivor of Antietam, Shaw drills his charges as if they were born and raised as free men. When they struggle with the processes of conventional combat, Shaw unleashes his frustrations on Washington's rebellious Private Trip.

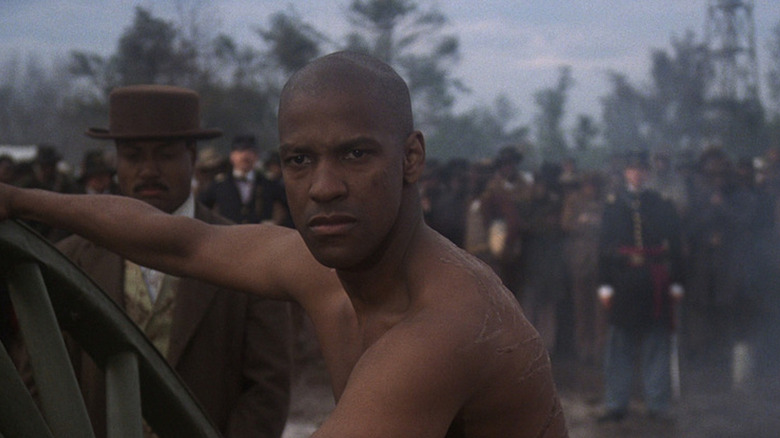

The nadir of Shaw's command is his decision to have Trip flogged for insubordination. Shaw is applying a then accepted form of punishment, regardless of race, for desertion. But when we see the scars on Trip's back, we cannot countenance this act. Shaw could relent, but he is hidebound to protocol and frightened of losing his command. He cannot allow Trip to undermine his leadership, so he goes through with the whipping. Trip spits in defiance and locks eyes with Shaw. He does not yelp. He barely grimaces. But when that solitary tear streams down his cheek as leather laces into flesh, Shaw finally understands the magnitude of Trip's fury. It's written all over the man's back. He literally has skin in this game. His skin and his soul are all he has. And if the war is lost, he doesn't even own that much. From this point forward, we're acutely invested in this story.

A moving monument to the ultimate sacrifice

Save for a dashed-off pan from Rolling Stone's Peter Travers, "Glory" earned enthusiastic notices from mainstream critics and serious film scholars alike. Zwick had proven himself as a visually accomplished director capable of telling a captivating story that had nothing to do with upwardly mobile white folks (and would go on to work with Washington two more times on "Courage Under Fire" and "The Siege"). The Academy was suitably impressed, nominating the film for five Oscars. Denzel Washington took home his first trophy (for Best Supporting Actor), while the great Freddie Francis won his second Oscar for Best Cinematography (which I view as a make-up award for failing to give him so much as a Best Director nod for any of his Hammer/Amicus horror classics).

Today, "Glory" is widely considered one of the finest films ever made about the first-and-hopefully-last U.S. Civil War. It continues to resonate because Zwick obsessed over surface and spiritual detail. He had a profound obligation to the brave men of the 54th, whose sacrifice saved a nation. He brought that Boston Common monument to vividly unforgettable life. Most Americans didn't know the 54th prior to "Glory." Now, thanks in large part to Zwick, they know to honor and cherish their memory.