The Chinese-Born Cinematographer Who Shaped Hollywood As We Know It

Outside of exceptions like "Citizen Kane" cinematographer Gregg Toland, the role of the director of photography in classic Hollywood was fairly anonymous. No matter the impact of their work on the public consciousness or their sculpting of unforgettable images, their names have historically been left out of the public discourse — being remembered by pocket communities of dedicated film historians or industry veterans who were influenced by their work. As James Wong Howe would say in a 1945 op-ed in "The Screen Writer," "when the photography of a picture is good, the critic usually praises the director for his understanding and handling of the camera."

Wong Howe himself worked with a number of phenomenal and well-known directors, from Cecil B. DeMille to Howard Hawks, over his five decades in the business. His reputation centered on finding new ways to express the story -– as he said in the same op-ed, "the best cameraman is one who recognizes ... the story as the basis of his work." In his limitless imagination within the camera and his fidelity to these stories, he crafted his own style, pioneering new innovations in the art of cinematography and even trailblazing a new path as one of the few Chinese-Americans to find that level of success in Hollywood.

He dealt with prejudice in getting to that point, the racial prejudices of the 20th century United States. As Wong Howe's assistant, future filmmaker Haskell Wexler would note in the LA Times, Wong Howe "was a boxer before he was a cameraman." He was on the defensive, and brilliant while doing so.

Beginnings

According to The Oxford History of World Cinema, James Wong Howe was born Wong Tung Jim in China in 1899, moved to the United States at 5 where a teacher Americanized his name, and spent his adolescence learning how to box. It was as a young adult that he grew interested in photography, moving to Los Angeles to work on the team of famed Hollywood director Cecil B. DeMille. His relative youth and passion for discovering and developing new photographic techniques meant that in a way, the art form of the cinema grew up with him.

DeMille couldn't have guessed that he was shepherding a major talent when he asked for Howe to operate one camera of a five-camera setup. According to Silentfilm.org, DeMille was trying to orchestrate a five-camera setup for his 1919 film "Male and Female" with Gloria Swanson (whose own relationship with DeMille would play a huge role in 1950's "Sunset Boulevard") and Wong Howe was available. That sent him to the bottom rung of the career ladder and gave him the education he would need in the fundamentals of cinematography.

Wong Howe, assigned to shoot stills of star Mary Miles Minter for 1923's "Drums of Fate," came up with a particular innovation to make the actress shine. According to Criterion, her naturally blue eyes didn't read well on the orthographic film of the day, and so Wong Howe set up a black curtain behind the camera that would create a natural hue for her eyes.

Never out of work

"The word went around at cocktail parties that Mary Miles Minter had imported herself an Oriental cameraman, who hid behind a velvet curtain and magically made her eyes turn dark," Wong Howe said, via Google Arts and Culture. "After that, I was never out of work."

Indeed, Wong Howe continued to trailblaze for the remainder of the silent era, a time of unfettered creativity for Hollywood's filmmakers. His work on 1924's "Peter Pan" suggested a mastery of fantasy filmmaking as well, using low-key lighting to build the mood. In the film's opening credits, he is listed simply as James Howe, the non-Americanized portion of his name totally erased. That would remain the case until some time in the 1930s.

By the end of the silent era, Wong Howe had returned briefly to China to "try to make travelogues," according to the Internet Encyclopedia of Cinematographers. While the project stalled, he came back to a new Hollywood — sound had hugely shifted production techniques and even established filmmakers needed to prove themselves. Howard Hawks, long before directing his wild, near-incomprehensible adaptation of Raymond Chandler's "The Big Sleep," hired him to shoot his 1931 prison drama "The Criminal Code." Wong Howe took the opportunity to again play with light and shadow in enormously effective ways, illustrating the weight of jail time by shooting with long lenses on prison yards and minimal lighting on characters' faces. He proved he was more than an artifact from the silent era.

Hollywood racism

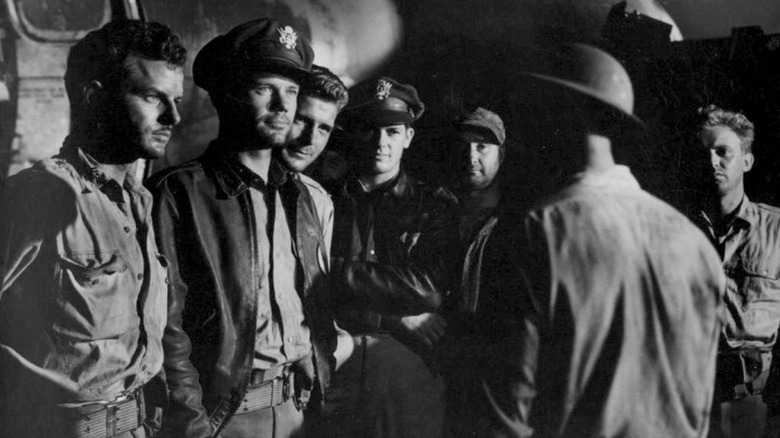

James Wong Howe also began to rack up Academy Award nominations, getting recognized for his work on Howard Hawks' 1943 propaganda war film "Air Force." It might not have been "Sergeant York," the Hawks war film that inspired Clint Eastwood to become an actor, but it does have Hawks' characteristic energy and elegance. It also reflects the xenophobic views of many Americans at the time towards Japanese immigrants, and the larger East Asian immigrant population.

If there was any suspicion about Wong Howe's values shifting towards assimilation, he was quick to deny it, even expressing an interest in making a Romeo and Juliet film with Mako Iwamatsu set in the Japanese internment camps set up by the U.S. in World War II. Unfortunately it never came together, according to an interview in "Moving the Image: Independent Asian Pacific American Media Arts."

Even if he was successful in the world of the movies, he would continue to be treated poorly by the country at large. Due to anti-miscegenation laws in the U.S., he and his white wife, activist and author Sanora Babb, had to wait several years for their marriage to be recognized. Babb even recalled Wong Howe getting into his boxing stance with loud racists, saying in the LA Times that he "got up and hit the man on the chin and knocked him out."

According to Babb's obituary, her left-leaning tendencies forced her to spend a year in Mexico so that the Communist witch hunts following World War II wouldn't ruin her husband's career. Wong Howe continued to work.

Wong Howe's innovations

To look at James Wong Howe's career from the end of World War II on is to see an artist in constant flux, learning new techniques and revolutionizing what the cinema could do over and over again. Look at "On the Waterfront," where Wong Howe's handheld footage and high-contrast nighttime photography gave the movie the grit it needed to let Marlon Brando change the art of screen acting. Or 1947's "Body and Soul," which saw him putting on a pair of rollerblades and skating around a boxing ring to get a more visceral feel from the fight sequences, according to the LA Times.

Beyond his work in film, he was a teacher of cinematography at UCLA's film school according to the LA Times, teaching among others the cinematographer Dean Cundey, who shot 1978's "Halloween" and "Who Framed Roger Rabbit." His influence went far, and he was even set to shoot Francis Ford Coppola's "The Godfather" before his illness took over in the early 1970s, according to Google Arts and Culture.Wong Howe is remembered today for his fierce devotion to his craft, his willingness to experiment in the art, and his bravery — both behind the camera, and in life.