Michael Mann Didn't Want Public Enemies To Be Just Another Period Piece

By the time director Michael Mann's crime drama-cum-biopic "Public Enemies" was released in 2009, the cinematic medium had existed for a full century. As a result, historical events lived in the public consciousness more than just in firsthand memories from those still living who experienced them; such memories of events had become superseded by films depicting them. In other words, the look of World War II had become synonymous with the look of a '40s movie, Vietnam and Watergate evoked images of '70s films, and so on.

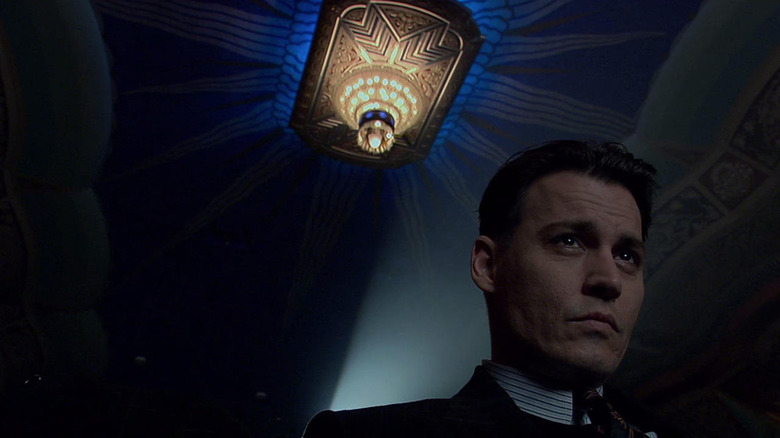

This was precisely the dilemma Mann faced when making "Public Enemies": how to differentiate his picture about the lives of John Dillinger (Johnny Depp), Billie Frechette (Marion Cotillard), and Melvin Purvis (Christian Bale) from the collective conception of the 1930s created by classic films from the period. The problem only became compounded when taking into account the importance of classic cinema to the real-life events — Dillinger was infamously shot down by authorities after attending a screening of 1934's "Manhattan Melodrama" — as well as the numerous films already made about the legendary bank robber, from 1945's "Dillinger" to 1979's "The Lady in Red."

Mann's solution was to embrace the rise of digital technology in filmmaking, enlisting the help of cinematographer and regular collaborator Dante Spinotti to create a look for "Public Enemies" that wouldn't rely on cinematic history and convention, but instead attempt to present the audience with a sense of reality.

Bringing the Dillinger legend down to Earth

Given the wealth of material generated around the John Dillinger legend, which encapsulates such various historical elements like Prohibition, gangster violence, and the formation of the FBI, Michael Mann's goal in making "Public Enemies" was to, in his words from a 2009 interview with the Guardian, "locate an audience intimately within the frame of [Dillinger's] existence and to experience some of that rush" of being a folk hero who is also labeled public enemy No. 1.

In attempting to make the characters and events of the film more immediate and tangible, Mann continued: "I didn't want audiences looking at 1933 ... I wanted to make them feel like they were in 1933." Using that distinction as his ethos, Mann and Dante Spinotti chose to shoot "Public Enemies" in HD rather than on celluloid. That choice led to the necessity of the set decoration, wallpaper, fabrics, clothes and other elements to be as finely detailed and researched as possible to hold up under the format's intense visual scrutiny.

Mann's complete commitment to authenticity was something he demanded of his cast and crew when making the film. His No. 1 requirement from his actors was immersion, something he believed he got from them as he observed to the Guardian:

"There's no work in this film by any of these fine, fine actors, starting with Johnny [Depp], that is performance. I mean, they are there. They're living it, and being it."

Becoming so immersed in the facts and inner lives of the historical figures meant that most dramatic license applied to the people in other films about them fell by the wayside, resulting in a movie that has as much empathy for Dillinger and Frechette as it does for Purvis and the other officers of the law who were involved. Unlike a melodramatic period piece, "Public Enemies" manages to feel like the most authentic, down-to-earth depiction of the Dillinger legend to date.

Mann finds reality in digital cinematography

When Michael Mann's filmmaking career began in the early 1980s, digital video was years away from being available as a tool. Once the director found himself able to use it in the late '90s, he embraced it concurrently with his desire to make movies featuring real-life events. "The Insider," "Ali," and "Public Enemies" all attempted to present historical reality as immediate as possible, while Mann made sure the more fictionalized stories of "Collateral," "Miami Vice," and "Blackhat" all had a similar basis in facts and intense verisimilitude.

Mann didn't adopt digital cinematography lightly; in fact, he made a point of shooting a series of tests when developing "Public Enemies" that compared film to digital to see which format carried the most reality with it. As he explained to the Guardian:

"I came away from the tests — we just brought a Sony F23 camera out there to look at it, to be diligent — and I looked at them, and that [celluloid] looked like a period film, and this [digital] looked like what it was like to be alive in 1933. In the end it made total sense: Video looks like reality, it's more

immediate, it has a vérité surface to it. Film has this liquid kind of surface, feels like something made up."

Digital cinematography has made a leap forward in fidelity and quality since Mann shot "Public Enemies," with digital cameras almost totally replacing film cameras on most productions, causing the debate regarding which format is superior to enter into increasing degrees of nuance. For his part, Mann continues to insist on a gritty, immediate look and sense of reality for his productions no matter the format, as seen in his latest project, HBO Max's "Tokyo Vice." The show is ostensibly a period piece, being set in the late '90s, but it doesn't attempt to evoke the look of a '90s movie or rely on any other such nostalgic trappings. For Mann, immediacy is the name of the game, which is just one of the reasons why he's such a continually compelling filmmaker.