How Francis Ford Coppola Saved American Graffiti From TV Movie Mediocrity

It's easy to forget nowadays, but "hangout movies" were once a novel concept. For those who are less familiar with the term, it's pretty self-explanatory. Hangout films are movies about people, well, hanging out for some period of time, often before having to go their separate ways. It's an ideal genre for directors who prefer to make low-budget films that reflect on the human condition, be it through comedy ("Dazed and Confused," "Clerks"), emotional drama (Richard Linklater's "Before" trilogy), or both ("Lost in Translation," "Licorice Pizza").

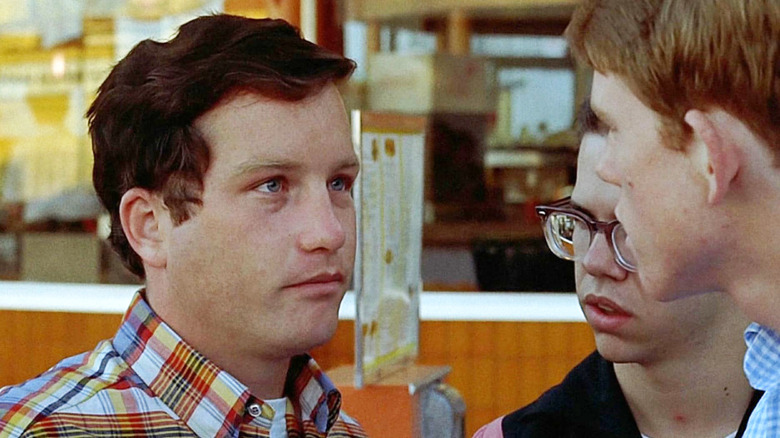

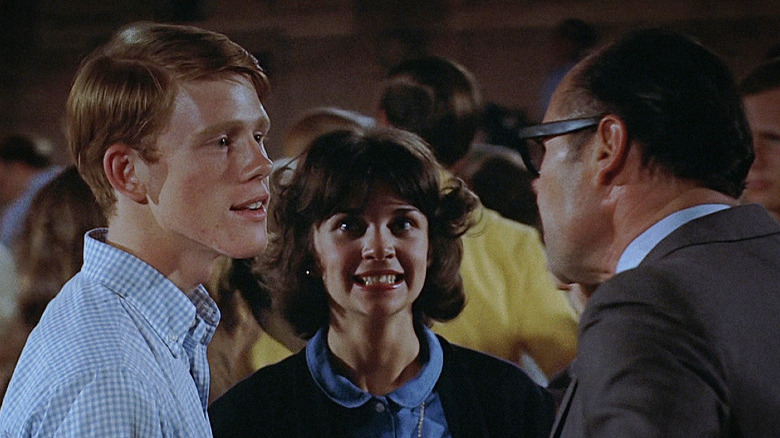

In many ways, George Lucas' second feature film as a director, 1973's "American Graffiti," is one of the earliest examples of the hangout movie as it exists today. The film centers on the escapades of a group of teenagers over the last night of summer vacation in Modesto, California, circa 1962. (Yes, even 49 years ago, Lucas' nostalgia for the '60s youth culture he grew up with was apparent in his work.) Richard Dreyfuss and Ron Howard star as Curt Henderson and Steve Bolander, two high school graduates and pals who are meant to be on their way to college across the U.S. the next day. However, Steve finds his heart is being pulled in a different direction towards his girlfriend, Curt's sister, Laurie (Cindy Williams). Meanwhile, Curt sets out on a quest to find "The Blonde" (Suzanne Somers), a mysterious blonde-haired woman who expressed her romantic interest in him before driving away in her Ford Thunderbird.

Studio executives didn't get it

Honestly, the above summary makes it sound like "American Graffiti" is more plot-driven and has bigger stakes than it does. The movie, by and large, plays out as an interweaving series of vignettes where those rascally Modesto teens get into trouble while cruising their home turf at night. Their antics rarely cross the line into being truly dangerous either, at least until the nearly-fatal drag race that acts as the film's climax. This scene, where Harrison Ford's boastful character Bob Falfa takes on Modesto's drag racer champ John Milner (as played by Paul Le Mat) was also an early showcase of what Lucas could do as an action filmmaker, four years before he made "Star Wars." But to the executives at Universal Pictures, which had funded "American Graffiti," this then-innovative type of cinematic storytelling was more confusing and worrying than exhilarating.

Yes, for all the ways "American Graffiti" looks and feels like an indie film, it was actually a studio movie that only felt "indie" due to its small budget. Universal initially granted Lucas $600,000, which would amount to a few million today, but upped that amount by $175,000 after Lucas' good friend Francis Ford Coppola signed on as a producer on the heels of his blockbuster success with "The Godfather." While it would go on earn positive test screening responses, that wasn't enough to convince studio heads that Lucas' film was anything more than a misfire unworthy of a theatrical release. In fact, as "American Graffiti" co-writer Willard Huyck recalled while being interviewed for a documentary about the making of the movie, Universal gave serious thought to re-editing it as a TV film instead:

"When the movie was finished, and Universal was very worried about it in every regard, you know, what they were going to do with it, there was talk of putting it on television, and they just didn't know what to do."

Coppola to the rescue!

Naturally, at the time that he made "American Graffiti," Lucas didn't have the ability to assuage the concerns of wary studio heads. After all, his first movie as a director, the avant-garde dystopian sci-fi film "THX-1138," hadn't exactly lit the box office on fire upon its initial release in 1971, grossing only $2.44 million. As such, it fell to Coppola to use his newly-gained clout at the time to save "American Graffiti" from being re-cut for TV.

"The executive from Universal was there, and he came up to me with a grave face, and he said, 'Well, we have a lot of work, we have a lot of work,'" Coppola recounted in the same making-of documentary mentioned earlier. "And I just couldn't believe that he didn't see what he had. George was cowering in the background, you know, because he didn't want to get in the middle of this."

Never one to waver in his support for his pal (much less stomp on Lucas' attempts to break new ground artistically), Coppola said he convinced the unnamed studio executive to change their mind:

"I remember telling the guy, I said, 'Listen, if Universal doesn't want the picture, you know I'll buy the picture today for what you have in it.' And I remember telling him, I said, 'You should get on your knees and thank this young man for what he's done for your career.'"

After some negotiating, Coppola was able to convince Universal's executives to reduce the number of scenes they wanted to drop and debut the movie in theaters as originally planned. (Those deleted scenes, as it were, were later restored for the film's release on the home market.) Whether they admitted or not, the studio's heads were no doubt ultimately thankful that he did: "American Graffiti" was both a critical and financial smash-hit that paved the way to Lucas making "Star Wars" and helped to further bolster Coppola's stature in the industry. Thus ends the tale of how one of the most influential hangout films of all time was spared from becoming a bland TV movie that, in all likelihood, most people probably would've never heard of.