Paul Newman Learned A Special Skill For This Cool Hand Luke Scene

Paul Newman was on a bit of a roll by the time he starred in 1967's "Cool Hand Luke," the sweaty prison classic that gave him one of his iconic roles. Over the previous decade he had established himself as one of Hollywood's biggest stars, a silver screen idol who had notched up three Oscar nominations for his intensely charismatic performances in "Cat On a Hot Tin Roof," "The Hustler," and "Hud." "Cool Hand Luke" would be his fourth. It would take another twenty years before he finally got his hands on one of those little golden fellas, for reprising his role as Fast Eddie Felson in "The Color of Money," Martin Scorsese's belated sequel to "The Hustler."

Newman plays Lucas Jackson, a decorated war veteran who is sent to a road camp in Florida for drunkenly cutting the heads off a row of parking meters. It's a pretty absurd reason to get yourself banged up, but the crime suits his nonconformist nature. He runs afoul of the camp's strict prison warden and quickly becomes a hero among his fellow inmates thanks to his rebellious antics and refusal to give up.

Adapted from Donn Pearce's 1965 novel of the same name, Luke is one of American cinema's great anti-authoritarian characters, along with Jack Nicholson's R.P. McMurphy in "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest." (Ken Kesey's novel came out three years earlier and was adapted for the stage, with Kirk Douglas playing the part on Broadway.) With the Vietnam War in full swing and civil unrest in the '60s, it's easy to see why these rebellious characters struck a chord with the public.

Newman lobbied for the role, which was originally intended for Jack Lemmon or Telly Savalas. Once he was given the part, Newman spent time in West Virginia to study people's accent and mannerisms. He also picked up another skill for a key scene in the film.

The Plastic Jesus scene

Earlier in the film, Luke receives a visit from his dying mother, Arlette (Jo Van Fleet), who has come to say farewell and let him know that she plans to leave her house to his brother, John. She says she always loved Luke more, so she feels that this is only fair. There is clearly a very frosty relationship between Luke and his brother, who has driven Arlette to the prison for the visit. They have also brought Luke's old banjo — "Now there ain't nothing to come back for," John says as he hands over the instrument.

Later, after Luke has completed his famous challenge of eating 50 hard-boiled eggs in an hour, he has become even more popular with the other prisoners. One evening, he receives a telegram to say Arletta has passed away. He silently returns to his bunk, and all the other guys leave the room out of respect. Luke picks up the banjo and starts strumming and singing quietly to himself. The song is "Plastic Jesus," and as the camera moves gently across the barracks to focus on his face, tears roll down his cheeks as he sings. After the second verse, he stops for a moment, then starts playing again, faster, louder, and more determined this time.

The original screenplay doesn't specify the song, but it is the perfect choice for the scene. With the irreverent lyrics that lightly poke fun at the kind of folks who might actually have a plastic Jesus in their car, we can see why it would appeal to a character as irreverent as Luke. Why does he choose this song at a time like this? Well, we don't get a huge amount of his backstory, but we get the sense that Arletta also had a devilish streak to her. Perhaps it's a song that gave them both a laugh in the past during happier times.

"Cool Hand Luke" is full of classic scenes — the egg-eating contest, Luke earning his nickname by winning a large pot in poker with a "handful of nothin'," and the saucy roadside carwash scene. Among all this, the "Plastic Jesus" scene is easily my favorite scene in the movie, with Newman's inexpert singing voice and hesitant banjo playing giving a flippant song an unexpected amount of tenderness and poignancy.

The Plastic Jesus song

"Plastic Jesus" was first put on vinyl by The Goldcoast Singers, comprising of folk singers George Cromarty and Ed Rush, as a humorous closer for their live album "Here They Are! The Goldcoast Singers." It was recorded as part of a college concert and they frame the song as a radio advert from the purveyors of plastic dashboard holy figures called the "Pink and Pleasant Icon Company."

They wrote the song back in 1957, inspired by a religious radio station in Del Rio, Texas, although at least part of it has roots in a much earlier African-American spiritual (via Song Meanings + Facts). In the intro on the album, they frame it as a humorous fictional radio advert from the purveyors of plastic dashboard holy figures called the "Pink and Pleasant Icon Company." They set the scene like this:

"Maybe you've had the same experience, driving along a very busy street in the afternoon traffic, with honking and screaming and scraping of fenders, and the sweating and swearing, and dust and noise and heat, and you're just glued to the wheel, and it's horrible, and the honking, and somebody's bumping into your bumper, and then you look at the car next to you, and the guy that's driving along next to you, is all cool and calm, and he has an expression of Buddha-like serenity plastered over his place, and you wonder why he is so serene. And then, possibly, you look to his dashboard and there you see, glowing in the afternoon sunlight, a four-inch high plastic icon that is apparently supplying this serenity to him."

Historically, there was some confusion over the authorship of the song when it was incorrectly attributed to Ernie Marrs, who recorded a version a few years later with extra lyrics. It was probably his version that Luke has in mind in the scene. Since then, it has received several cover versions from a wide variety of artists including Tia Blake, Billy Idol, Jello Biafra, and The Flaming Lips. For my money, no one does it as well as Newman, and to pull it off he needed to do one thing: learn how to play the banjo.

Paul Newman learns the banjo

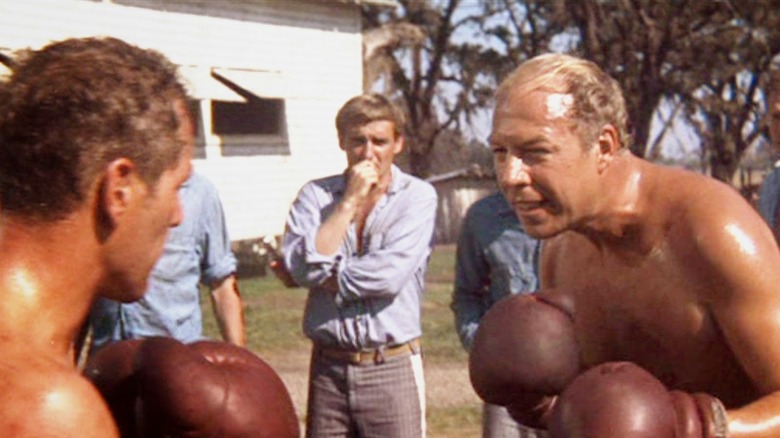

Paul Newman studied method acting under Lee Strasberg in New York and he wasn't against going the extra mile to prepare for a film. For his first starring role as middleweight fighter Rocky Graziano in "Somebody Up There Likes Me," he trained with real boxer Tony Zale. Zale had fought the real Graziano three times for the championship and had to be replaced for the role of himself when he hit Newman a bit too hard (via NYT).

Newman also wanted to perform his own shots in "The Hustler," despite having never played pool here (via Mental Floss). He had a pool table installed in his apartment so he could practice in the weeks leading up to the scenes. So when it came time to shoot a scene in "Cool Hand Luke" where he needed to play the banjo, Newman wasn't about to let his lack of banjo skills stop him. As George Kennedy, who plays Luke's burly rival-turned-best-friend Dragline in the film, told EW:

"Paul knew as much about playing a banjo as I know about making cakes, which means very, very little, but he wanted to play his own accompaniment, and director Stuart Rosenberg and everybody else said, 'You don't learn to play banjo that easily.' And he said, 'No, I'm going to try.' And [in] the scene you see, Paul makes an error. He wasn't doing it the way he wanted and became madder and madder ... although you can only [tell] by the increase of the pace of his picking the banjo. When it was over, it was magnificent. Rosenberg said, 'Print.' Paul said, 'I could do it better.' Rosenberg said, 'Nobody can do it better.' And that's the way that came off. True story."

Knowing this certainly gives the scene an added dimension. Luke clearly isn't a virtuoso from the way he plays, and that makes sense for his character. He's a drifter and a rebel, someone who might tinker around with the instrument from time to time without ever putting the time in to get really good at it. It's a cool fact, and you know what is even cooler? The legendary Harry Dean Stanton, who has a small role in the film, taught Newman how to play "Plastic Jesus" for the scene.