Disney's Robin Hood Started As A Different, Darker Movie

Disney's 1973 retelling of "Robin Hood" introduced generations of audiences to the sly and suave anthropomorphic fox version of the literary hero, inspiring many to sing the song of "Oo-De-Lally" and countless others to suddenly question why they suddenly felt those feelings toward a fox. Walt Disney had wanted to adapt the tale of a wily fox who battles a corrupt medieval king as an animated movie all the way back during the making of his first full-length feature, "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs," in 1937. Only Disney hadn't originally planned on making "Robin Hood" the way we know it today, but rather the tale of "Reynard the Fox," the vulpine protagonist of medieval Dutch fables. The Reynard stories present him as a trickster figure, not unlike the way foxes are presented in Japanese lore (I'm looking at you, Redd from Animal Crossing). The Reynard tales were written in the Middle Ages and were viewed as morality tales for children, but also parody stories of medieval literature, providing a satirical look at political and religious institutions.

Walt Disney really wanted to make a movie about Reynard, but faced difficulty as the character is more of an anti-hero at best, and wholly unsympathetic at worst. The stories were all in the public domain, eliminating any royalty payments the Disney company would have to make, but there's a pretty massive issue with the "Reynard the Fox" stories — they're bleak as hell.

The Original Script Ended With A Lot of Death

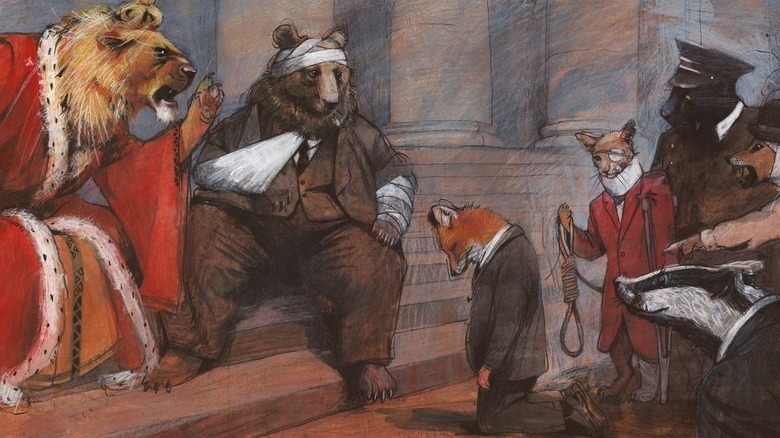

As Cartoon Research reports, Walt Disney had assigned writers Dorothy Blank (who also worked on "Snow White") and Al Perkins to come up with a script, specifically one that included scenes of disguises and escaping danger just in the nick of time. After a movie full of hijinks, Reynard is finally captured and the King orders he be executed by hanging. While in the gallows, Reynard confesses that his father once tried to overthrow the King, with help from his uncle, the Wolf. His father also supposedly hid a massive amount of wealth inside a volcano, which sends the King and the royal subjects on a trip into the volcano to find the treasure ... and most of them are killed when the volcano erupts. The King manages to survive, frees the Wolf from prison, and the Wolf and Reynard have a duel, with Reynard winning through trickery.

A royal ball is thrown in Reynard's honor for winning the duel, and he steals the royal treasury while everyone is partying their faces off. He is again captured, and begs not to be banished to the volcano. They exile him there anyway, but he digs up his father's treasure and smiles slyly at the village. His master plan had worked all along. Needless to say, other executives at Disney were worried about the story, especially given the restrictions of the Hays Production Code, which controlled what kind of content could be explored in Hollywood movies at the time. Walt Disney was also worried that the story was too sophisticated for their growing family audience, and felt the realities of Reynard were less "Robin Hood" and more glorifying of a crook. "He's not to be a murderer under any circumstances. He shouldn't take advantage of anybody but a stupid individual," Disney said.

The Building Blocks for Robin Hood

The "Reynard the Fox" film was put on the shelf for many years, until writer and production designer Ken Anderson felt inspired to tell a story through anthropomorphic animals rather than humans like in "The Aristocats." Anderson was inspired by the unused ideas from the "Reynard" plan and incorporated it alongside the Robin Hood story as specifically told in 1952's "The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men." Some of those working on the production held very closely to the Reynard story, specifically the animal hierarchy as presented in the Reynard stories. Foxes were seen as medieval burglars, the monarchy was represented by lions, wolves were shown as law enforcement, and smaller animals represented the public as a whole. The only animal that falls out of the pattern is Little John the brown bear, as bears represented landlords in the Reynard stories.

Anderson had attempted to depict the Sheriff of Nottingham as a goat, trying not to fall into animal stereotypes, but lost that battle to director Wolfgang Reitherman. He also wanted to include all of the Merrie Men, but was again overridden by Reitherman, who wanted Robin Hood and Little John's relationship to serve as a "buddy picture" like "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid." Friar Tuck was turned into a friend of Robin's living in Nottingham, and Alan-a-Dale was turned into the narrator.

While the final product may not have been exactly what Anderson had in mind, the Disney Company probably made the right call to not pursue the bleak Reynard stories in favor of the much more family-appropriate "Robin Hood." After all, we probably wouldn't always have "Oo-De-Lally" constantly stuck in our heads if the other version got made.