The Kids Controversy Explained: Contentious Child's Play

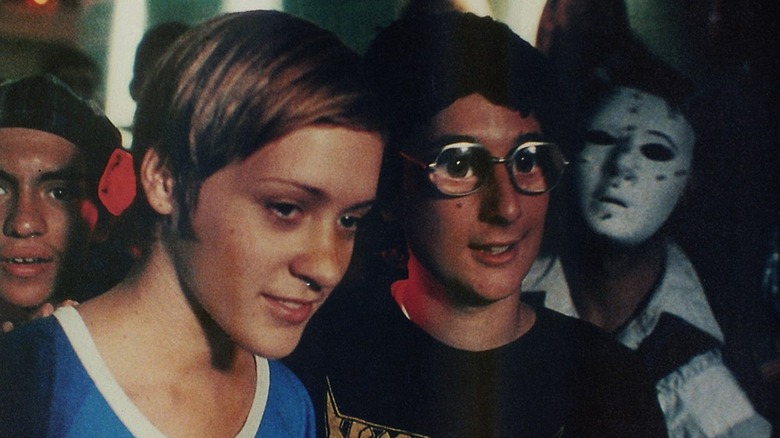

When your films are as esoterically titled as "Gummo," "Julien Donkey-Boy" and "Trash Humpers," there's bound to be a messed-up filmmaking origin story lurking in your early adulthood. For transgressive auteur Harmony Korine, this certainly proves true. Before he would go on to helm the neon-soaked "Spring Breakers" or the slacker cinematic classic "The Beach Bum," Korine's first venture was a script which "honestly" (and crudely) portrays the delinquent and depraved behavior of NYC teens, a faction that the 19-year-old Korine was enmeshed in at the time. Directed by the oft-lascivious photographer Larry Clark and starring Chloë Sevigny and Rosario Dawson in their first feature roles, the film follows the literal exploits of Telly (Leo Fitzpatrick) and his best friend Casper (Justin Pierce), teenage skateboarders living in NYC.

While "Kids" certainly could have passed as a gritty coming-of-age film set amid the skate scene in Washington Square Park, Korine wanted to depict the seediest side of this subculture as possible, with the plot ultimately devolving into AIDS diagnoses and statutory rape. Though Korine and Clark claimed the film was an unvarnished portrayal of the problems of real-life adolescent New Yorkers, it was met with equal parts critical praise and backlash upon its release. Said to have captured drug use, alcohol consumption and sex among minors, the ethics of crafting such a film — despite its "authenticity" — immediately came into question.

Let's dig into the controversy which still surrounds the film 26 years later, and the legacy which continues to cement "Kids" as a relative masterpiece.

The Backstory: Skatepark Soulmates

Despite there being nearly three decades separating them in age, Clark and Korine were immediately excited to collaborate together. According to an oral history of the film conducted by Rolling Stone, the two met through both hanging out at Washington Square and Tompkins Square Parks, in the West and East Village of Manhattan, respectively. Fitzpatrick recalls the initial reaction to Clark within the teenage skate scene of New York City:

"Larry was always lurking around. Nobody really knew what his deal was, because he was 50 at the time, and always had a camera. Now, kids don't trust adults, especially adults with cameras...In order for Larry to photograph something, he has to be part of it. He can't just be an observer. So, at 50 years old, he taught himself how to skateboard so he could keep up with everybody. None of us knew what an artist was. We didn't understand that there were cool adults, adults that think teenagers have something of value. Our whole life was getting kicked out of spots, being told we were losers. And Larry was like no, what you guys are doing is cool."

Of course, Korine was among the crew of ne'er-do-well youths, himself attending NYU's writing program. Freshly transplanted from his hometown of Nashville, Korine commuted into Manhattan from his grandmother's home in Queens. Already an aspiring filmmaker, one day Korine handed Clark a VHS tape with some of his films and his phone number scrawled on the sleeve. Surely enough, he was impressed with what he saw, and invited Korine to write a script for Clark to direct. After writing 12-13 pages per day over the course of a week, Korine's script was finished:

"We wanted to make a kind of insider's look at this gnarly adolescent culture that you would never get to see otherwise — like 'The Real World' pushed into something hyper and insane. Neither Larry nor I were interested in making a documentary. It was conceived of as a piece of pop filmmaking. At the same time I was coming out of skate culture where things were super aggressive, and it was exciting to try to make something that was confrontational and provocative in that way...You can't discount how excited I was, and we were, with the idea of making people — and grown-ups specifically — angry."

As it turns out, several grown-ups were immediate supporters of the film, warts and all. Gus Van Sant and Martin Scorsese were among the film's early producers (though neither would be attached to the project upon its release), and Dinosaur Jr./Sebadoh's Lou Barlow was brought on to curate the film's soundtrack. Yet the dysfunctional energy of the dynamic between Clark and Korine was immediately palpable to any and all who interacted with them, Barlow included:

"They were quite a duo. It wasn't a father-son thing — it was way creepier than that. They took me to a really high-end sushi restaurant and were telling me their whole plan of making this groundbreaking movie that was going to win an Oscar, and when they accepted their Oscar they were going to walk to the podium to this Slint song 'Good Morning Captain.' They had it all mapped out."

They may not have gotten the Academy Award they anticipated, but Barlow did include Slint's "Good Morning, Captain" in the film, which played over the end credits.

How Did the Titular Kids Get Involved?

Most of the cast was already baked into the existing skate scene of the city, meaning the majority of them were first-time, non-professional actors. Fitzpatrick and Dawson were the youngest principal cast members, being 14 and 15, respectively. Sevigny was 19, and Pierce, alongside co-stars John Abrahams and Harold Hunter, had just turned 20. While there exists an overarching narrative that these kids probably had no idea what they were getting into with "Kids," their interview responses show that a few had the direct support of their parents — namely Dawson and Sevigny, who continue to be successful working actors to this day:

"I had just graduated eighth grade, and I was hanging out on my stoop on Avenue C," said Dawson. "I lived in what had been an abandoned building, a squat basically...So they gave me a script, I read it and my parents read it, and they thought it was cool. Most people would have read that script and said 'Oh hell no!' But the only issue my mom and dad put their foot down about was that my character couldn't be smoking. Otherwise they thought the film seemed really smart."

Sevigny had a similar story, though her road to "Kids" was a bit less spontaneous. She met Korine in Washington Square Park during her senior year of high school, and moved to the city shortly thereafter, living in Brooklyn Heights with a motley crew of die-hard rave kids and working at Liquid Sky, a rave-centric retail store. Despite having the NYC party scene at her feet, she briefly left New York for San Francisco to follow a boyfriend. This move didn't stick, though — she came back to New York after receiving word from Korine that he was shooting a movie and wanted to cast her in it. Back in Connecticut after having given up her Brooklyn apartment for the California move, she asked her father if this was truly the right decision for her:

"I showed my dad the script and asked what he thought about it, and he said I think you should do it. You've always wanted to be an actress — it's something I did all through school, at summer theater camp. I had been doing music videos and stuff, trying to figure out a way into that world. It just seemed like a natural trajectory."

At first, Sevigny was cast in an ancillary role as one of the girls in the swimming pool scene, with Mia Kirshner (the iconic if divisive Jenny Schecter on "The L Word") originally cast as Jennie. However, Kirshner did not vibe well with the non-professional actors already attached to the film, and she was fired as a result. Thus, Sevigny took the role — imbuing a surprising amount of gut-wrenching sincerity to the role of a young girl who gets diagnosed with AIDS shortly after losing her virginity to Telly.

Unsavory Set Practices

If the entire plot of "Kids" wasn't enough to send viewers into a pearl-clutching moral frenzy, the chaotic and irresponsible approach to depicting adolescent sex and drug use certainly did the trick. One of the most instantly recognizable scenes in the film focuses on a group of 12-year-old boys puff-puff-passing, and several sources have confirmed that the young cast was "plied with pot" on-set. With the added burden of depicting statutory rape, virginal de-flowering, and crudely sexual talk among teens, the fact that an intimacy advisor was nowhere to be seen during production is rightfully concerning. Though 19-year-old Korine penned the script, many felt it was Clark's responsibility as the ostensible adult of the crew to make sure these young adults weren't exploited during filming:

"[Clark] was throwing them into a situation that might have been a little over their heads—I mean everyone talked about giving head or whatever, but what was their experience with sex?" said cinematographer Eric Edwards. "Are we asking them to do more than their experience has been?"

To his credit, Clark certainly did grapple with the limitations of what he was able to show on screen, especially when it came to the extensive drug use of the young actors, many of them smoking weed constantly in their everyday lives. However, when teenage drug use is openly condoned during production for the mere sake of "accuracy," a moral conundrum is bound to arise:

"Drugs were a big thing," said Clark. "Obviously those kids were smoking dope in the park. There's no illusion about that. So at some point that became a thing: Can we legally show kids smoking dope? And what does that mean?"

Dawson and Sevigny also had conflicting opinions on the validity of their characters' actions. Rosario was a born-and-bred New Yorker, so she felt the script truly emulated the conversations she would hear among her peers at school and around the neighborhood. But she knew that these conversations were total farces, utilizing intentionally shocking dialogues meant to falsely convey how "mature" or "sexy" girls who had been playing with Barbies just the year before had become. Sevigny, who hails from Connecticut, felt the dialogue to be a bit over-the-top, herself stating she mostly "dry humped" with skater boys during this period of her life.

The ordeal is perhaps put most saliently by Fitzpatrick, who contextualizes the dramatized essence of acting intersecting with the tendency for young people to posture about their sex lives:

"All these kids were basically acting. Because they weren't even that sexual, they were like 15, 16. So they're all trying to put on airs, saying like, 'there was this one time when I had this girl,' and blah blah blah. But it was all a front. That's what acting is. I had had sex once, maybe. Maybe not even real sex. I didn't know what the f*** I was doing."

The Consequence of Kids

Unfortunately, the legacy of "Kids" has had a dark shadow loom over it following the death of several cast members. Pierce died by suicide just five years after the film premiered, and Hunter's drug-related death in 2006 added to the profound devastation among the film's surviving cast. Hamilton Harris, who played Hamilton, recounted his experience during filming in an interview with Deadline:

"Twenty five years ago, yes, I felt exploited. Yes, I felt, 'Aw, man, I thought it was going to be more than it actually was.' Twenty five years later, today, in my late 40s, I see differently. From an ethical standpoint, yeah, I wouldn't do it that way. I'd do it differently. It's not my place to say whether or not Larry is right or wrong. I think each of us can decide what that is for ourselves."

Yet "Kids" can't be wholly discounted, as it did jump-start the cinematic careers of several of its central collaborators. Korine's independent-turned-commercial filmmaking career flourished as a result, and Clark also went on to direct several features (many of which were praised by Roger Ebert), including 2002's "Ken Park," which was also written by Korine. Sevigny would continue to star in a string of independent features, even garnering an Oscar nod for her role in 1999's "Boys Don't Cry." Rosario Dawson similarly rose to prominence after the film, appearing in Spike Lee's "He Got Game" three years after her performance in "Kids."

For all of the success "Kids" has offered many of its central players, the immense tragedy which would plague other cast members can't be written off. A time capsule of shocking, scintillating '90s independent cinema, even Korine admits it's a product of its time, likely never to be attempted ever again:

"That movie could never exist today. I don't even know what the laws are now, and what the rules are. I just don't think any of it could happen. I was stoned for a lot of it."