Star Wars TV Is Finally Giving Tusken Raiders The Spotlight, And It's About Time

As a near-lifelong "Star Wars" fan, I've found that enjoying the galaxy far, far away gets exponentially harder as years pass. My identity as a woman of color, as well as the constraints that come with it, staunchly influences my opinion on everything. So I've found that my appreciation for "Star Wars" — a decidedly-white franchise that has only recently begun seeking out minority voices — now hinges exclusively on how said voices are elevated (or — let's be real — ignored).

Lucasfilm has a pretty shoddy history of inclusion, at least in its live-action "Star Wars" properties. Until very recently, the films had little to no representation to speak of, and most of it was appropriative. Most of the alien species of "Star Wars," particularly those of the prequel era, are also closely linked to racist caricatures. From the Gungans of Naboo to the Neimoidians of the Trade Federation, very few have broken free from their harmful depictions. But with Lucasfilm's pivot to Disney+ and the rise of "good 'Star Wars' TV," one group is finally getting the justice they deserve: the Tusken Raiders of Tatooine.

The Tuskens' Complicated History

A kind of primordial groan resounds across the fandom whenever "Star Wars" returns to Tatooine for any reason. It feels like we've been "returning to Tatooine" for everything lately, and the storyline is often as barren as the planet's sand-swept topography. It's coarse. It's rough. It's irritating. What more could they feasibly have to show us there?

The answer, according to "The Mandalorian," is a brand new side to the Tusken Raiders.

The Tuskens (née "Sand People") have always had a kind of enmity with the Skywalkers — they nearly killed Luke in "A New Hope," and indirectly murdered Luke's grandmother, Shmi, in "Attack of the Clones" — as well as the other (mostly white) settlers on Tatooine. Until "The Mandalorian," the Raiders were always painted as one of the many hostile, uncivilized fixtures of the planet, and it didn't help that they were very clearly inspired by real-life indigenous nomads.

"The Mandalorian" didn't exactly retcon the Tuskens' trademark ruthlessness, but it did confirm that they weren't nearly as mindlessly violent as they'd always been portrayed. In Season 1's "The Gunslinger," Mando's first adventure on Tatooine, the bounty hunter is actually able to communicate with the Tuskens. The series created Tusken Sign Language with the help of deaf actor Troy Kotsur (who recently starred in the AppleTV+ movie "CODA"). They even expanded on the Tuskens' spoken dialect, which until that point mimicked the bray of a donkey ... something I have never enjoyed.

With a Little Help From a Mandalorian...

Din returned to Tatooine (are you primordially groaning yet?) in season 2. That first encounter gave way to an alliance between a Tusken tribe and the settlers of Mos Pelgo, one orchestrated by Din. For the first time, they had a common enemy in the legendary Krayt Dragon — a creature vaguely introduced, along with the Tuskens, in "A New Hope" — and they defeated it together. (Well, it was mostly Din. But their victory was very much symbolic of all they could accomplish with a bit of mutual understanding.)

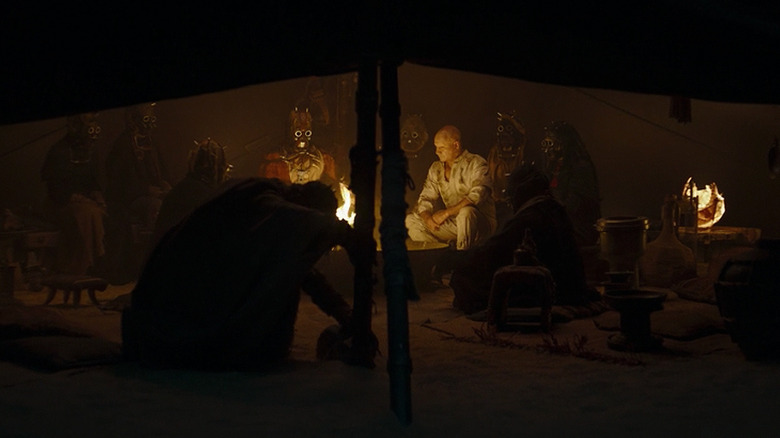

"The Mandalorian" wasn't entirely able to shake the ol' "Cowboys and Indians" motif (it is, after all, merely a Western in space), but it seems "The Book of Boba Fett" is doing what it can to subvert that dynamic. Many assumed Boba Fett had spent time with the Tuskens after his infamous Sarlacc escape: He sported a baller Tusken-inspired fit before reclaiming his trademark armor in "The Mandalorian," and even wielded a gaffi stick against a group of stormtroopers. "The Book of Boba Fett" confirms that theory right out of the gate, and in doing so, gives us an even closer look into the Tuskens' inner world.

Granted, Boba didn't merely stroll into a Tusken camp and ask for a place to lay low. He essentially becomes their slave before eventually earning their respect and working his way into the tribe. And it's a bit jarring, not only to see such an "untouchable" figure like Boba made so vulnerable, but also to see him humbled by the same people who later join forces with another Mandalorian. In some ways it feels like a backslide, but it makes sense because it "humanizes" the Tuskens without completely abandoning their pricklier attributes.

...Make That Two Mandalorians

The Tusken Raiders are just like any other indigenous alien in "Star Wars." Like the Gungans or even the Ewoks of the original trilogy, they're slow to trust the outsiders trespassing on their land, but are fiercely loyal to those who earn their respect. Boba, as seen in "The Tribes of Tatooine," earns that and more. Not only does he coax them from their misgivings with technology, he also defends them — and their ancestral land! — from the invasive Pyke syndicate.

This sort of "Dances With Wolves" narrative can get old fast when it's a white man adopting the "simple" cultures of the Other. But Temuera Morrison, who first gave a face to Jango Fett and later Boba, is deeply in touch with his own indigenous roots. As a result, he was able to influence the Tusken culture in turn.

"I come from the Maori nation of New Zealand," Morrison told The New York Times in 2020, "and I wanted to bring that kind of spirit and energy, which we call wairua."

Morrison imparts his cultural dance, the haka, to the Tuskens. Even the manipulation of the gaffi stick was inspired by the Polynesian fighting style. By the end of "The Tribes of Tatooine," Boba has been trained to fight as the Tuskens do, and performs a ceremonial dance with the entire tribe. It's a moment that put a surprising smile on my face. It warmed my heart to see the Tuskens — a group coded not only as people of color, but as a monolithic threat in general — treated with such reverence.

A Surprising Shift

It's a shame that it's taken so long to see a side of the Tuskens that other "Star Wars" natives have always intrinsically possessed. But in a way, "The Book of Boba Fett" was the perfect opportunity to reveal it. The series was touted as a descent into the criminal underworld of "Star Wars" and a closer look at the hard-hearted Boba Fett fans expected to see. However, its parallel storyline, while lifted from the godfather (wink!) of all gangster flicks, pulls most of the focus to Boba's time with the Tuskens. This has disappointed fans who were really gunning for a darker, more grounded "Star Wars" title, myself included. It was only "The Tribes of Tatooine" that changed my mind for good.

While this subplot may seem tedious to some, it does address the bantha in the room, one that couldn't be ignored in yet another Tatooine-based story. The Tuskens aren't savages, they're people. And this might be a reach, but they're also a kind of family to Boba, a character who spent a great deal of time searching for belonging. If you don't believe me, watch "The Clone Wars" — it does a wonderful job depicting Boba's rocky coming of age, and the string of ill-fated alliances he endured before finally going solo.

It may not be what anyone expected or wanted, but it is a natural progression from the events of "The Mandalorian." It even makes Boba a sort of foundling in his own right. The success of the Tusken arc is twofold, in that it endows the maligned raiders and Boba with some much-needed substance. That Morrison was able to bring his own culture to "Star Wars" makes Boba Fett a perfect fit among the Tuskens. He's not the cynical guy who treats bounties as cargo. Not anymore, anyway. Maybe the Tuskens had a hand in reversing that. And again, that's a surprising shift for a character that has lived rent-free in the minds of generations. But it's made me care about "Star Wars" again, so I'm definitely along for the ride.