The 20 Best Feel-Bad Movies You Need To Watch

Watching a film is always an emotional commitment. We empathize with the characters, good and bad, and we stay invested in what happens to them. With many movies, we're looking to feel something positive as the credits roll. A sense of victory, or relief, or, frequently, happiness depending on the type of film. But sometimes we're looking for a weirder catharsis. We're looking for the downer movie. We want to be haunted. The reasons why are complicated, but it comes down to being human.

These are the bleakest films I can recommend for those days where you just don't want to feel good. Some of them offer hope that things will turn out okay, after all. Then they don't. Some build castles out of dread, beginning with the lingering sense that things aren't alright and ending with more than enough detail to prove the point. None of them end on a cheerful note. After viewing any of these, please take care of yourself. You'll have better days ahead than these poor saps.

Threads

By 1984, the world had spent decades gripped by the paranoia surrounding the Cold War. The United States and the then-Soviet Union were in constant conflict, and the specter of nuclear war was a frequent topic. Scientists like Carl Sagan began to push back against the concept of a survivable nuclear strike, explaining the new idea of nuclear winter and the wide-ranging ecological impacts of the fallout. Then the BBC released "Threads," a small budget nightmare that looked at the likely results of a full-scale nuclear conflict, and nobody in England has slept right since.

That's hyperbole, but barely. "Threads" begins like "Coronation Street," with the town of Suffolk going about their normal business. A pair of young lovers deal with an unexpected pregnancy. Local politicians man the phones, assuring their people all is well. All to the background noise of rising conflict in the Middle East. The bombs don't fly until roughly an hour into the film, and the rest is some of the bleakest stuff put to celluloid. There is no happy ending. There's barely an ending at all. But the film is uniquely watchable for the probable horrors it demands we think about. It's a film that's changed minds, and troubled our hearts ever since.

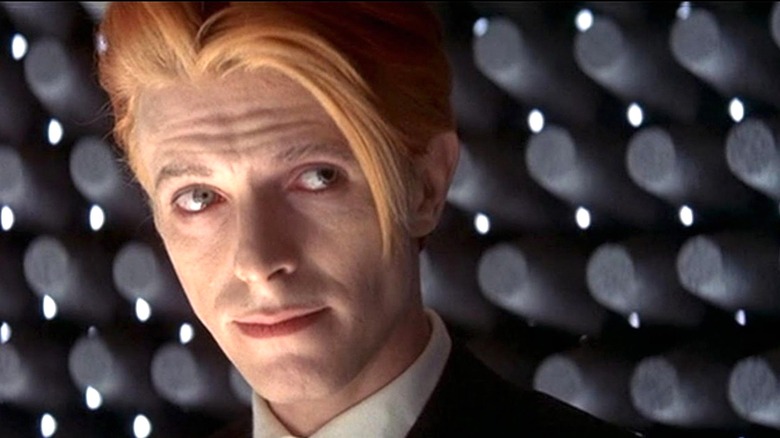

The Man Who Fell to Earth

David Bowie was a master of multiple mediums, and his acting gigs, while uncommon, are almost all fine quality performances. Nicholas Roeg saw in him the perfect outline for a story about the consuming disasters of fame, casting him as the well-meaning alien Thomas Jerome Newton in "The Man Who Fell to Earth." Glimpses of the film suggest a psychedelic, drug-fueled romp through the back alleys of excess, and that's fairly accurate. David Bowie, at his most beautiful, romps naked or nearly naked through a sizable chunk of the film. He's ethereal, distant, and singularly perfect.

And yet, the final half-hour of the film could induce depression in Mr. Rogers. Newton's memories of his family have long since begun to fade. Paranoia and torture have rendered Newton's ability to prove himself as anything other than human moot. His imprisonment turns him into a shell of a person. All he has left is his unnatural beauty, and his excesses, his only comfort, will eventually ravage that, too.

Cloverfield

Kaiju films are fun to watch, even as they often carry loaded commentary about the selfish folly of humanity versus the natural world. We, the audience, are usually placed far from the action, peeking in with the scientists and enjoying the special effects extravaganzas as Godzilla slaps the beans out of his foes. But 2008's "Cloverfield" did something else. It put the audience down on ground level, following its cast from behind a sometimes-nauseating handheld camera as a kaiju attack on New York City turns horrifyingly personal.

The hour and a half long movie starts with some slow-paced character drama that begins to drag once the going-away party kicks into gear. But things go from awkward to hellish fast, saving the flick. "Cloverfield" leans into our post-9/11 nightmares, with the sudden mayhem-inducing, crowd-crushing panic and an instantaneous military response. The ending is black as a trucker's cup of 4AM coffee, erasing the last few hopes anyone, in the film or in the audience, might've had left.

Miracle Mile

"Cloverfield" might have changed the game for modern kaiju films by virtue of its audience participation in the horror of it all, but its narrative twist from character drama to "everything sucks" feels borrowed from a slightly obscure flick called "Miracle Mile." Our main character, Harry, quickly falls in love with Julie, but fate makes him miss his chance to meet her again after her shift at the diner. He turns up anyway, tries to call her from the public phone booth outside, and intercepts a phone call meant for someone else. A desperate-sounding man claims there's maybe an hour left before nuclear war. Then he's shot, and the call ends.

Suddenly this cute "Harry Met Sally" style rom-com turns into a horrific slow burn as Harry wonders if what he heard from the man on the phone was true. His breakdown inside the diner turns chilling when one of the other patrons reveals she believes him, and gives proof. The rest of the film is a real-time nightmare of Harry doubting his sanity while trying to reach Julie before time runes out. Since it's on this list, you know where this is going. It's a ride to the end of the world.

Videodrome

David Cronenberg isn't known for his feel-good movies, although some of them push the envelope further than others. "Videodrome" is one of his earliest major successes, a bloody commentary on social media, taboos, and the philosophies of Marshall McLuhan. James Woods plays the cultured sleaze hound Max Renn, president of a UHF station that plays material you don't admit you watch when you're visiting family. Renn, obsessed with commercializing the next popular taboo, falls into a carefully laid trap. Militarized moral guardians have hijacked both medium and message, and they're ready to kill everyone that's not up to their clean-cut standards.

It's eerie stuff, and "Videodrome" is still talked about as the movie that predicted today's internet and its shifting moral controls. Ever relevant as websites sanitize themselves while still showcasing us at our most awful, the movie rockets down a playground slide into unreality and body horror. We don't know what's real for Renn by the end. But his fervent acceptance of death and transition in the film's final moments is chilling to watch.

Carrie

Stephen King nearly gave up on his premiere novel, "Carrie," until his wife, Tabitha, fished it out of the trash and urged him to complete it. Brian DePalma pulls on the same thread I believe Tabitha found inside Carrie White's life of abuse and desolation. It's relevant, awful, and somehow comforting. Carrie went through her brief existence believing she was alone, unique in the most terrifying of ways. It's poignant to realize that she never was. We're all here with her.

Both the film and the novel start at a crucial twist in Carrie's life. The first period a woman gets is stressful at any age and education level, and Carrie's been given no tools to understand what's happened to her. She's mocked and pushed aside. It's the first aggression against her that we have to endure, and it's far from the last. Her eventual revenge is thorough and horrifying. It's also blackly satisfying. This is a movie I come back to when I'm upset and depressed. I doubt I'm the only person who does. It doesn't make you feel better, but it helps to know you're never alone.

The Mist

Frank Darabont's adaptation of Stephen King's short story "The Mist" is infamous for making King himself say 'hahaha oh wow!' at its sharply intensified, depressing finale. The fact that "The Mist" has a downer ending is less of a spoiler than it used to be these days, but for those seeking an imaginative, quality ride through a bored daydream gone to hell, this flick continues to ride supreme.

The premise remains a comfortable twist on zombie apocalypses and government experiments gone awry. "The Mist" rises above comfort with excellent performances from nearly everyone, but especially Thomas Jane as the paternal protagonist and Marcia Gay Harding as the avatar of every faux-religious jerkwad we've had to deal with lately. The effects are the third star of the show, with horrific, half-seen eldritch nightmares dipping in and out of the eponymous mist. The whys and hows of this interdimensional mistake go unexplored, like the best Lovecraft-lite tales of woe. The impact on humanity stays in focus. And like the most haywire round of "Arkham Horror," Thomas Jane's attempts to survive end the way we fear – while the camera, like some monstrous eye, never blinks.

Grave of the Fireflies

Famously known as the movie you'll never watch twice, Studio Ghibli's "Grave of the Fireflies" nevertheless demands it be watched once. The elegiac, heart-stopping beauty of this film etches the too-real horror on a viewer's very bones. Ghibli's talent for squishy expression and lush backgrounds makes the desolation into something so personal and real, it forces emotion out of the hardiest of us.

The US's firebombing campaign against Japan is less well understood than the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but its effects on Japanese civilians were often as devastating. But the film isn't an indictment of the West. Instead, Japan's social mores and insistence on personal honor are targeted. Seita and Setsuko are children, devastated and orphaned. No one, not even their aunt, whom they live with for a while, is empathetic enough to help Seita understand what he needs to help his sister survive. Rations are slim. Refugees are numerous. The ending is a foregone conclusion, one that reminds us of our own empathy, and shames us for not using it more often.

The Road

You know those nightmares you get where almost everything is a dull grey, sound is muffled, nobody feels like they can move at high speed, and you're not sure what went wrong in the world but clearly everything's gone to crap? Haha, no, that's not a nightmare, you're just watching the film adaptation of Cormac McCarthy's everything-sucks masterpiece, "The Road."

"The Road" is the only film on this list with a potential glimmer of hope left in its ending, but I'm here to dash it for you. If "Threads" established that a post-nuke world is ice-skating uphill towards scant recovery, the apparent total loss of a thriving biosphere means that the remaining characters of "The Road" might live with some shreds of comfort before everything falls still for a few millennia. The Earth may someday recover, and I hope the squids take over our planet next, but Viggo Mortenson's kid isn't growing up to raise ponies in Saskatchewan.

No Country for Old Men

Nothing like a Cormac McCarthy one-two punch. As a writer, McCarthy's bona fides cannot be in doubt. As a person, I refuse to denigrate a man I will likely never meet — but I also feel like he's not the kind of guy to own a fun Christmas sweater. There's nothing fun about "No Country For Old Men," either, though there's some sly, dry humor hiding in the dialogue between its earthy but doomed cast of characters.

It helps that the film is a Coen Brothers joint, who lift the nihilistic despair of the original story and its indictment of human nature into something more melancholy. It's, in a chronological sense, the last true Western. Its characters are the final generation to have memories of the collision between whites and indigenous tribes. But such conflict never really ends. It just varies its participants, and a single sheriff can't change the world. The sheriff's kinsman suggests it's vanity to believe he ever could. In the final moments, Tommy Lee Jones shares a dream about hope, about the fire carrying on. It's only a dream. Probably.

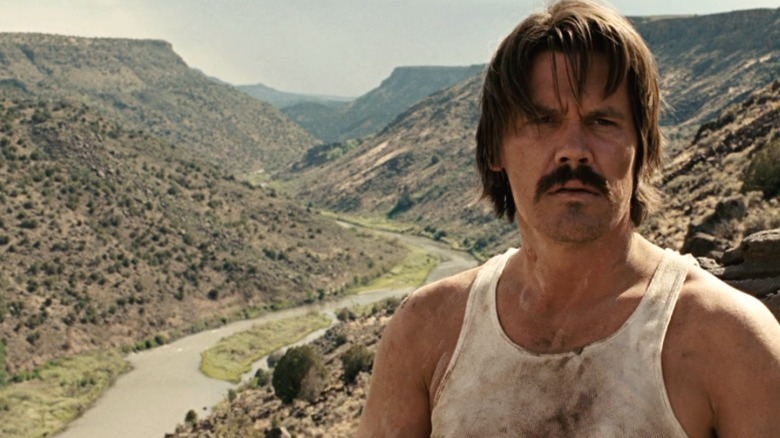

Sicario

Villeneuve's "Sicario" can be mistaken for a high-octane thriller about the real world strife between drug cartels and law enforcement, and certainly the ill-advised sequel assumed it was. But it's actually another nihilistic character study with exactly one good and moral person trapped at the crux of the film's legal and moral conflicts. And she gets completely screwed over.

Okay, "Sicario" is also an excellent, high-octane thriller. The border crossing shootout is the most tautly-made sequence of its kind since Michael Mann's "Heat." There's a big part of us that wants to root for Josh Brolin and Benecio Del Toro, even when we know what they're doing is not only unethical, but dehumanizes the issues the film's dealing with. The outcome is fatalistically honest. The CIA has once again given up on doing the right thing. Instead, they've chosen a preferred puppet cartel, and will play by its murderous rules. Emily Blunt's idealism does nothing more than slow their decision. Her final encounter with Del Toro's Alejandro is tinted with cynical mercy — the same cynicism that the city of Juarez will live with every day.

Logan

Wolverine is one of the most popular characters in comic book history, sometimes to a fault. The occasional X-Man, with his gruff and tumble yet sensitive storylines, is an unending well of character drama, with new scenes pulled from his amnesiac history on the regular. Killing him off never takes, and even the most apocalyptic storylines leave us with a sense that Wolvie will always come home again. With or without his adamantium skeleton, flip a coin.

"Logan" takes all that in and gives back a sense of growing discomfort. The absolute steel spine it took to make this movie is an achievement in itself. It dares to bring in Patrick Stewart, the best version of Professor Xavier we could have been granted, and trap him in the nightmarish thrall of his enfeebled mind. It then grants him a final memory of his old friend, Logan, as his murderer. Finally, the film wraps it all in a Cormac McCarthy-style flourish where all our heroes are dead and the children have no guarantees they'll be alright. "Logan" isn't just a comic book movie. It's one of the best depressing films in a generation. Thank God it's not mainline canon.

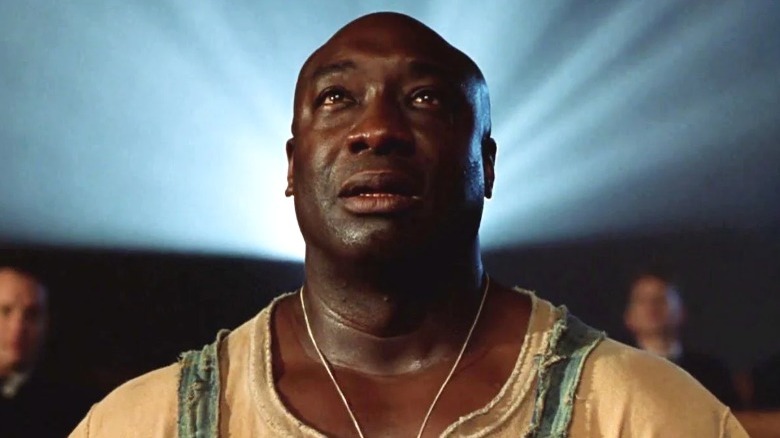

The Green Mile

Frank Darabont haș a gift for taking Stephen King's stories and making them hurt even more. "The Green Mile" is a gift package of excellent character actors, giving David Morse and Jeffrey Demunn equal footing against Tom Hanks and Michael Clarke Duncan. It's beautifully shot, with dreamlike nostalgia imbuing a troubled past. It's clever and sometimes heartwarming. And yet, nothing about this movie makes anyone feel good by the end.

The fact that the events of this film center on an early iteration of Death Row is the first suggestion that this glimpse of history isn't going to be as bucolic as we'd like to think. That nostalgia is its own weapon, too, as guilt and mundane human horror relentlessly build into the present day. Meanwhile, John Coffey's gentle gift isn't enough to overcome the cruelty we can inflict on each other, and it's brought him too much pain to want to carry on. As for Tom Hanks and his role as a firm but good-hearted prison guard? The only kindness the film offers over the book is that we don't glimpse the full hell he endures as he ages alone.

Hereditary

Ari Aster's feature film debut, "Hereditary," is designed to shake the hardiest of souls. Sweet girl Charlie is set up as an emotional pawn between her mother and her recently deceased grandmother, and there could have been more than enough drama in that dynamic to fill a trilogy. But that's not the sole issue getting unburied in this broken family, and Charlie's story is resolved via the most nightmarish events a family could fear to suffer.

Aster never pulls back, never relents, turning the second half of the film and its characters into a psychological panini press. The demonic influence hinted at throughout the film becomes less of a metaphor for broken families and more of a holy-god-he's-going-there literal summons to evil forces humanity was never meant to bargain with. There are countless stories about why one doesn't make deals with devils. "Hereditary" puts its twist in the reveal that it has a happy ending — but not for the protagonists we've suffered with.

Fallen

Preceding "Hereditary" is a lesser known Denzel Washington joint. 1998's "Fallen" is one of the best curios to come out of the sudden rash of religious horror that preceded the turn of the century. There's a lot to unpack about that interesting fact elsewhere, but "Fallen" earns notice for being a modern noir with a devilish twist. It's all here, the long-timer detective with a string of closed cases. The one case that still haunts him. The copycat that fixates on the detective and his family. The reveal that it really is all connected.

The dark-soul'd gag here is that the copycat killer isn't a vengeful relative of the serial killer Detective Hobbes stopped. It's the same killer, transcending beyond death because, well, it's a demon. Hobbes defies this fact for as long as possible, leaving the story in a creepy limbo until he can't deny it any longer. The sequence where Azazel showcases its power to some acoustic Rolling Stones is one of the most effect moments of dread in film. And like "Hereditary," the only happy ending belongs to the wrong character.

When the Wind Blows

"The Snowman" is one of those twee holiday charmers, a beloved bit of English whimsy that's crossed the pond and immigrated into our hearts. But creator Raymond Briggs offered fans a follow-up that, at first glimpse, is just as whimsical and charming. Unfortunately for your next good night's sleep, "When the Wind Blows" is about as comforting as the holocaust memoir "Maus." The animated adaptation, with its soft voices and music from David Bowie and Roger Waters, amplifies the cuteness, and thus, the subsequent nightmares.

The "cozy catastrophe" is a divisive genre of apocalypse fiction, suggesting it's possible to weather the worst with a cuppa and a biscuit if you're plucky enough. "When the Wind Blows" deconstructs all possible coziness with a sledgehammer. Its elderly couple survived the Blitz, and surely by following all of that well-meaning government advice, they'll survive nuclear war, too. But this story has more in common with "Threads," and like its predecessor, it's willing to showcase just how bad that advice is. The outcome is known within minutes, but like this sweet old couple, you'll keep on suffering till it's over.

12 Monkeys

Terry Gilliam's time travel thriller, "12 Monkeys," is one of his most accessible films. It's not quite mainstream, with its unsettling cinematography and bleak, sometimes obscure plot. But it's a stunner of a movie, with a terrific early performance by Brad Pitt, and a reminder that Bruce Willis can be excellent when he's not phoning it in.

"12 Monkeys," in addition to its discussion of fate and immutable destiny, is also about how we perceive our reality. It's seldom clear whether Willis' James Cole has retained his sanity during his doomed mission to stop a deadly virus. Braided into Cole's other troubles is a weighty metaphor for Messianic rescue, and like Christ on the cross, Cole's fate is sealed the moment he's dropped back into time. Unlike Jesus, Cole isn't aware of or consenting to his role as a sacrificial lamb, and his few disciples aren't enough to comfort him as time seals its fated loop.

Soylent Green

Science fiction movies prior to 1980 can come off pretty cheesy today, and 1973's "Soylent Green" is no different. With Charleton Heston at the height of his scenery-chompin' career, and some hammy gusto laid over the few sequences set at the police station his cop, Frank Thorn, works at, it may be tough to settle in and see what the film really offers. But try.

The ending of "Soylent Green" is unspoilerable now. New generations are born already knowing that Heston will wail that Soylent Green — the tasteless, inoffensive nutrient cracker that may be all someone ever gets to eat — is made from people. But the revelation is built from a quiet yet shattering revelation that happens much earlier in the film. Frank's friend Sol carries that plot thread with poetic serenity, choosing to die in peace to guide Frank to the answer. It's not just that Soylent Green is people. It's that the oceans are dead, and soon we will have nothing left at all.

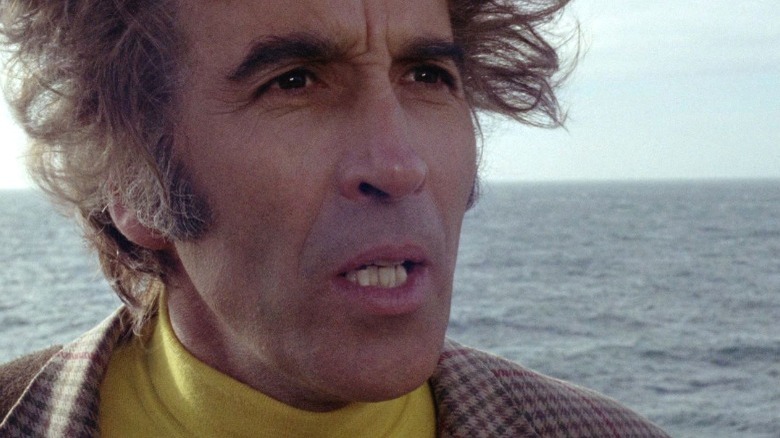

The Wicker Man

Horror films go through recurrent streaks where obscuring their gory reveals create effective scares. It's a technique that films like "Alien" have mastered, even where other films stumble and frustrate us. But unblinking daylight horror can provide an unsettling sensation that can't be otherwise matched, and the pastoral beauty of Summerisle is its own character in the psychedelic folk horror "The Wicker Man." The 1973 one. Not the Nick Cage in a bear costume one.

"The Wicker Man" hides a rich vein of cynicism under its innocent pagan veneer. The reclusive town believes in the rituals that might bring back their harvest, but their patron, Lord Summerisle, is less certain a figure. Christopher Lee inhabits the dual role of island lord and high priest with unquestionable authority — yet he's masterful enough to ensure the questions seep in, anyway. The climax is a vision of Hell on a perfect morning, but Sergeant Howie, damning himself with his howls of vengeful fury, is the last man to dare speak what Summerisle secretly knows. The island's never getting that bountiful harvest back.

The Fly

David Cronenberg finishes out this list with a remake that doesn't try to surpass the Vincent Price original. It creates a new world of its own, leaving its predecessor equally perfect. Cronenberg's vision of "The Fly" uses body horror not just to disgust, which it does, but to highlight the dwindling humanity left inside of Seth Brundle.

The steadily increasing gore is artful in that it draws you to look closer, even knowing that watching how Brundlefly eats will put you off snacks for a couple of days. But it's also a relentlessly emotional film, and the only catharsis it allows Brundle is the sweet release of death. There's little hope in this perfect nightmare. The final scene, which in a lesser film would give its survivors time to come to grips with what they've endured, instead hard cuts to credits just as Geena Davis realizes it's finally over. There's no relief to be found here. It's just done.