The 20 Best Italian Horror Movies Of All Time

Italian horror is most often associated with Giallo, a sub-genre containing gaudy color palettes, overly complicated plot lines, and flabbergasting reveals. While there are plenty of films within this entrancing cinema classification, Italian horror transcends this stylistic boundary. It also includes psychological terrors, ghost stories, straight-up slashers, tales about demons and the undead, and countless other varieties of nail-biting yarns.

Italian filmmaking pioneers like Mario Bava, Dario Argento, and Lucio Fulci established many of the horror conventions we've come to know and love 一 and often broke their own rules in the process. Sensible story structures are regularly sacrificed for style, mood, heightened surrealism, and garish cinematography that evokes a film's particular messaging. Set design and murder sequences sometimes emerge as characters themselves. Italian horror is nothing if not subversive, guiding the viewer through a trembling, cob-webbed house of horrors both beguiling and extravagant.

The unexpected is the expected. When a narrative doesn't make much sense, you can always rely on imagery to squirm like earthworms into your brain. The genre makes an oath: It will terrify you, and will give you nightmares for days, weeks, and months on end. Our selections for the 20 best horror movies in Italian cinema encompass everything from starkly-lit allegories about human existence to gore-drenched slashers and thrillers that will shake you to your core

Demons

The "Demons" soundtrack includes songs by Billy Idol, Motley Crue, and Rick Springfield, which should clue you into the tone of the film. It's a delicious banquet of sex, drugs, and rock 'roll, with some flesh-hungry demons thrown into the mix. With a script co-written with Dario Argento, based on a story by Dardano Sacchetti, Lamberto Bava (son of Mario Bava) uses the movie-going experience to stage a 1985 apocalyptic rager. From ghastly gore, including puss-filled gashes that pop like pimples, to visceral, colorful photography, it easily ranks alongside the likes of Lucio Fulci's "The Beyond," which is also on this list.

A group of strangers accept an invitation to attend a late-night preview for a new horror flick. As a band of 20-somethings unintentionally spark the end of the world onscreen, real life imitates art and soon all hell breaks loose. Trapped inside the theater, the movie-goers attempt to barricade themselves away from a swarm of demons, but their best efforts are for naught. They become a literal concession stand of flesh, bone, and blood, the single location feeling both limitless and claustrophobic. The imagery in this film is so nauseating that you may want to have a wastebasket handy.

Black Sunday

Mario Bava is credited as a director on three previous films, including 1958's "The Day the Sky Exploded." Due to numerous on-set fiascos, Bava often swooped in to take over the reins to finish filming — see, for example, "I Vampiri," which was originally directed by Riccardo Freda. As such, one could argue that "Black Sunday" is his proper directorial debut; his artistic fingerprints are present on his preceding works, but this haunted 1960 chiller is completely his own.

A vampiric witch, Asa (Barbara Steele), and her beloved Javutich (Arturo Dominici) are sentenced to death for sorcery and their faces impaled by a demon mask, an iron maiden-like contraption with spikes lining the interior. It's a surprisingly brutal opening scene that sets the tone for a downright bone-rattling entry into Italian cinema. As with many films of the era, "Black Sunday" relies upon the power of suggestion and disturbances in the human mind.

Two centuries later, Asa's descendent Katia, also played by Steele, must confront her troubled familial history. When a careless doctor and his protegee accidentally awaken Asa from her glass-encased tomb, Asa and Javutich seek to quench their bloodlust by dropping bodies in their wake, and reclaim lives long-extinguished. A delicate slow-burn, Bava's film immerses the viewer in startling images, the most arresting of all being Asa's newly-reborn face etched with dark crevices. It's the sort of nightmare fuel that doesn't go for immediate frights, but instead burrows into your skull.

Short Night of Glass Dolls

Aldo Lado's first feature retools Giallo expectations and completely upends its usual structure to tell a gripping tale about human futility in the face of death. Having written scores of screenplays in his impressive career, Lado never leaves an impression quite like he does with "Short Night of Glass Dolls." When a young journalist named Gregory Moore (Jean Sorel) investigates the death of his girlfriend, he finds himself entangled in a sticky occult web.

Lado tells the story out of chronological order, often flipping between the present and the past as a way to keep viewers on the edges of their seats. In the opening scene, Gregory's body is discovered in a bustling plaza in Prague, assumed to be dead. When the mortician examines his body, all signs confirm that he is no longer alive, yet Gregory very much is. He's simply trapped inside his own mind, unable to move or utter a single sound. Left on a cold slab, he retraces the moments leading up to his grisly "death" and the discovery of what really happened to his darling paramour.

"Short Night of Glass Dolls" is far bleaker, both in story and style, than many of its contemporaries, but it's not without Aldo's tremendous thematic punches. As the final act closes in, and more revelations emerge regarding the cult, a comatose Gregory soon becomes an anatomy lesson for a group of students. The finale is among the most twisted and cruel endings in all of horror history.

Suspiria

When the topic of landmark Gialli is discussed, many cite "Suspiria" as a definitive standout. But here's the thing: Dario Argento's 1977 film is not a Giallo. It certainly lives among the stylish grandeur of many of Argento's other works, including "Tenebrae" and "The Bird with the Crystal Plumage," but its witchy, supernatural exterior shatters any possibility of it fitting within the Gialli box. "Suspiria" is among Argento's weirdest, most mind-melting explorations into human curiosity and womanhood, as it follows ingenue Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper) upon her arrival at a German dance academy.

Volumes of style and composition frame buckets of blood, always hyper-stylized and surreal in a way that makes you think it's all a figment of Suzy's imagination. Is it? Or is it not? The truth of the matter is that bodies are falling all around her, and seemingly random disappearances hint that the school's mysterious history is firmly rooted in sinister practices. A coven of witches, beholden to founder Helena Markos, invites young women into its fold before offering up their lifeless corpses as sacrificial lambs. "Suspiria" also features an acting style that's nearly as over-the-top as the set design and cinematography. That's the charm. Everything in "Suspiria" is heightened to such a degree that you simply get lost in its twisted, blood-soaked wonderland.

A Bay of Blood

Mario Bava's 1971 film "A Bay of Blood" (or "Twitch of the Death Nerve," as it's also known) plays generously in both the Giallo and splatter sandboxes. While borrowing the colorful dexterity of one of his previous works "Blood and Black Lace," the masterful filmmaker seems to take cues from such flicks as "Blood Feast," with graphic depictions of violence and buckets of blood. The bayside setting proves to be an essential ingredient as well, permitting Bava to lay the groundwork for many of the slasher era's biggest releases, including "Friday the 13th" and "Sleepaway Camp."

"A Bay of Blood" unfurls in classic Giallo fashion: murder, mystery, and mayhem. Count Filippo Donati (Giovanni Nuvoletti) strangles and hangs his wife, the wheelchair-bound Countess Federica Donati (Isa Miranda), in a murderous pact with real estate vultures Frank and Laura Ventura. But after Filippo has upheld his part of the deal, he is unceremoniously murdered and his body tossed into the lake. Frederica's death sparks salacious news coverage, leading a group of teenagers to invade the property for a little naughty time. The middle portion of the film almost reads as a long-lost Jason Voorhees saga, as each sinful teen commits horror's most egregious sin: having sex. Bava eventually brings the film full circle in the finale, and true to the convoluted nature of Giallo, it's a wild, yet totally well-earned, climax.

Stage Fright

Michele Soavi worked extensively with Giallo trendsetter Dario Argento, with credits as second assistant director for "Tenebrae" (1982) and director of 1985's documentary "Dario Argento's World of Horror." He took studious notes, as evidenced with his proper feature film directorial debut, "Stage Fright." Released in 1987, it's a very late bloomer in the overall slasher boom of the 1980s, but its Giallo flourishes elevate it far beyond its schlocky contemporaries.

An escaped mental patient sets his sights on a local troupe of actors, who are in the throes of rehearsing a musical about a mysterious murderer called the Night Owl. When one actor is found butchered in the parking lot, the ill-tempered director, Peter (David Brandon), insists that everyone go into lockdown and rehearse through the night. It's an outlandish premise only matched by the flamboyant owl mask, which was once worn by the actors onstage and then co-opted by the unseen killer.

"Stage Fright" not only embraces the dramatic, it stitches in overacting and absurd plot points like sparkling rhinestones on a nudie suit. The film proceeds as all slashers do, but Soavi doesn't pretend it's anything but what it is. Shocking imagery — particularly when the killer poses as an actor and reenacts a murder from the show, with the rest of the cast looking on from the audience — turns the blood cold in a way that's truly unforgettable.

Don't Torture a Duckling

When you think about Giallo directors, Lucio Fulci's name is near the top of the list. His body of work is extensive, and zeroing in on his definitive films is always an arduous task. 1972's "Don't Torture a Duckling" turns the Giallo screws so tight they nearly shred apart, making it one of the defining masterpieces of the era. In addition to a story centered around child abduction and murder, a terrifying set-up, the legendary filmmaker tosses in witchcraft, drug addiction, and subtle religious commentary for good measure.

The disappearance of a young boy named Bruno sends his parents into hysterics and unleashes an unruly mob, as well as a media frenzy. When the parents receive an anonymous phone call that demands a ransom, the cops set a trap to capture the culprit. As it turns out, the scruffy-faced caller was simply an opportunist and didn't actually kill the kid; he only buried the body deep in the woods. This revelation triggers a harrowing series of events and several more child murders, including a drowning in a town square water trough. Fulci leaves you guessing (and second-guessing) the killer's identity until the last possible moment. No kidding: The final 20 minutes contains so many misdirects that you likely will have trouble keeping up.

Black Belly of the Tarantula

The title alone is enough to send creepy-crawlies down your spine. Paola Cavara's 1971 Giallo "Black Belly of the Tarantula" more than lives up to its name. A masked stalker has a very particular way they prefer murdering woman, first paralyzing them with a wasp-like serum and then carving out their insides. Genre star and Bond girl Claudine Auger plays spa owner Laura, who finds herself in the eye of a blood-drenched cyclone with no way out. As her clientele drop like flies, every possible sign points to her as the killer.

But is she? The rubber-gloved psychopath weeds their way through sordid love affairs and those seeking to blackmail various adulterers. There might be a connection — at least Cavara wants you to think as much. With the body count rising, Inspector Tellini (Giancarlo Giannini) questions not only his ability to handle gruesome serial murders, but his own sleazy proclivities, now on full display. Cavara's creative decision to include sensual sighs and toe-curling moans in the score, primarily created by Ennio Morricone, creates a tantalizing treat, coating the entire picture with a provocative filter you could just die for.

Blood and Black Lace

Mario Bava wields the power of color with great effect. 1964's "Blood and Black Lace" blends the organic vitality of human blood (many of the set pieces are works of art in and of themselves) with the synthetic, highly manufactured beauty of posh fashion. Each frame is carefully constructed to evoke high-life glam, but still manages to root its glistening showpieces in a gnawing eeriness. And then, Bava perfectly wraps splashes of color and blood with a bow of intrigue and delight.

"Blood and Black Lace" flows with skin-tearing tension, low on story and high on visual feasts. It makes sense, then, that the story focuses on an upscale fashion boutique, the strenuous climate of competition among designers, seamstresses, and models mirroring the killer's pursuit for a missing diary that contains tawdry secrets about the firm's staff. Bava outlines human desperation with bright poignancy, using color to guide the rhythm and tone of the film. Story is superfluous to Bava's sheer elegance, and you won't second-guess his intentions once you behold each blood-curdling window display.

Lisa and the Devil

This must be what it was like to live inside Mario Bava's head. "Lisa and the Devil" is a nightmarish tumble down an "Alice in Wonderland"-like rabbit hole. A brilliantly strange specimen, this examination of Lisa's (Elke Sommer) grip on reality ends up becoming one of the genre's most relentless and fascinating exploits. Released one year after "The Exorcist," a global blockbuster success, film producers reportedly inserted additional footage, with Bava's son Lamberto Bava at the helm, to flesh out the supernatural elements and pepper in more explicitly exorcism-related themes; the film was later re-released under the title "The House of Exorcism."

While visiting Toledo, Spain, Lisa wanders away from her tour group and attempts to purchase a dummy from a local vendor before being spooked and running off. She eventually makes her way to a derelict mansion, the home of a cast of oddball aristocrats who harbor filthy secrets, including necrophilia. Moral lines blur, as well as those between reality and fantasy, when resident Maximilian claims that Lisa is actually his long-lost lover, Elena. Mentally disturbed, he dresses her in Elena's gowns and tries to rape her, provoking Elena's ghost to elicit chilling, resounding guffaws. "Lisa and the Devil" is as bonkers as it gets, leading into a "Carnival of Souls"-worthy crescendo.

Opera

Did "The Scottish Play" damn this film before it started? Perhaps. Infamously, the production of "Opera" in 1987 was marred by numerous tragedies and on-set difficulties. Director-writer Dario Argento's father died, his romance with principal player Dario Nicolodi ended, and another central actor, Ian Charleston, was involved in a car crash. Superstition or not, Argento's creative choice to include Verdi's "Macbeth," an opera based on the Shakespeare play, within the story may have been the harbinger for a series of unfortunate events.

In "Opera," Cristina Marsillach plays Betty, an understudy taking on the role of Lady Macbeth after starlet Mira Cecova (Daria Nicolodi) is hit by a car. The leather-gloved maniac makes their first appearance on opening night, peering through an empty box, and then kills a stagehand. Throughout the film, the murderer rips out pages from the "Macbeth" playbook; they appear driven by someone else's insatiable bloodlust, rather than their own carnivorous hungers.

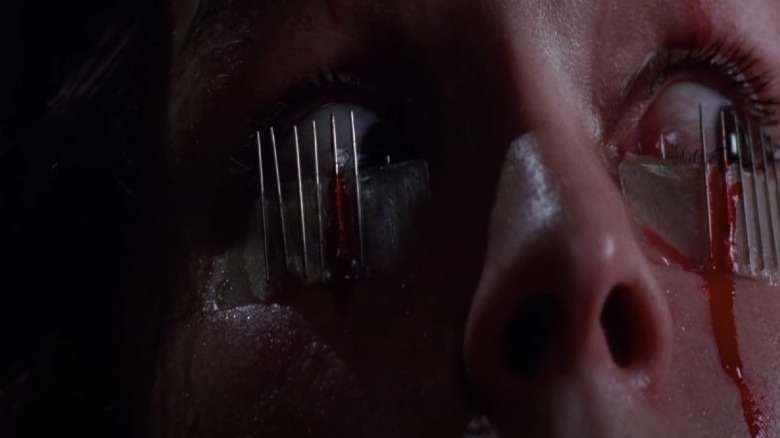

Later, Betty spends the night at her boyfriend Stefano's apartment, a decision she soon regrets. The unknown assailant breaks in, ties her up, and tapes her eyelids open with needles, forcing her to witness Stefano's brutal slaying. Argento reuses this scenario several more times throughout the film to chilling effect. It's a game of cat and mouse, and it all seems to indicate that the killer knows Betty, or at least has knowledge of her past. Often heralded as the last great Giallo, "Opera" is not for the faint of heart.

The Beyond

In "Splintered Visions: Lucio Fulci and His Films" (via Daily Grindhouse), Fulci says that to truly appreciate the mastery in "The Beyond" you have to understand that "it's a film of images." The filmmaker's 1981 feature draws upon Southern Gothic imagery, such as a sweeping, ethereal Louisiana estate, and supernatural frights to tell a story that may make some quite queasy. There's a reason why U.S. censors chopped the original version of the film down, cutting out violent sequences and many of its gorier scenes.

Unbeknownst to her, aspiring actor, fashion designer, and model Liza Merrill (Catriona MacColl) comes from a wealthy family. Upon the death of her uncle, she inherits a cursed piece of property down in New Orleans, a tract of land allegedly situated upon a gate to Hell. If we've learned anything from horror movies, it's that you never build a house on burial grounds or entries to the underworld. Respecting the dead, in general, is a good rule of thumb.

But several warnings from a blind woman named Emily (Cinzia Monreale) fall on deaf ears, and Liza finds herself in the direct path of a horde of zombies, spiders, and other slithering creatures. She joins forces with Dr. John McCabe (David Warbeck) to put the puzzle pieces together from a book titled "Eibon" and one of her uncle's mysterious paintings. "The Beyond" is an excruciatingly stomach-churning experience — if you hate spiders, you may want to avoid one particular skin-crawling sequence in which arachnids eat a man's face.

All the Colors of the Dark

Delusions born out of trauma are woven into the fabric of horror history. In Sergio Martino's 1972 "All the Colors of the Dark," forged in equal measure with Edwige Fenech's imposing performance and an effective application of light and shadow, Jane navigates the aftermath of a miscarriage. She's also still reeling from the childhood murder of her mother, so her emotional and psychological states are shaky at best. Her life in shambles, she seeks the confidence of new neighbor Mary, who suggests that she attend Black Mass, a ritualistic ceremony held by local Satan worshippers.

Martino baits you in with the promise of mystery and witchcraft. What you experience is so much more. "All the Colors of the Dark" submerges the viewer into the driver's seat of the unreliable narrator; we see what Jane sees, and you'll begin question your own sanity, or complete lack thereof. Her descent into madness is very much your descent, too. It's as if you took Roman Polanski's "Rosemary's Baby" and fed it into a colorful Giallo blender, tossed in a few supernatural elements with Gothic flakes, and set it on high. It's unexpected and thrilling and will leave you gasping for air.

What Have You Done to Solange?

Writer-director Massimo Dallamano conceals the identity of Solange (played by Camille Keaton, best known for her role in exploitation flick "I Spit on Your Grave") for nearly 80 minutes. Released in 1972, "What Have You Done to Solange?" is as much about lost innocence as it is about seduction, sex, and sisterhood. A group of young girls take part in a secret society, frequently throwing sex parties, and when a tragedy befalls one of them, an unspeakable act incites murderous retribution.

The girls pay a heavy price for what they've done, and their deceitful web ensnares gymnastics professor Mr. Enricho Rosseni (Fabio Testi), who has plenty of secrets of his own. His reputation as a philandering creep ignites suspicion with the local police, even though his illicit affair with a young girl named Elizabeth (Cristina Galbó) gives him an alibi for the film's first slaying. So, it can't possibly be him, right? Dallamano's feature spirals like a hypnotist's wheel, and once all is revealed about Solange, you'll be unshakably disturbed.

The Red Queen Kills Seven Times

We've all heard the urban legend of Bloody Mary — or perhaps you're more familiar with the one about the babysitter and the man upstairs. Emilio Miraglia's 1972 Giallo "The Red Queen Kills Seven Times" explores an urban legend about two royal sisters, the Black Queen and the Red Queen. Every 100 years, legend has it that the Red Queen, once slain by her envious sister, returns and seeks revenge by killing seven people.

A disturbed painting hung in aristocrat Tobias Wildenbrück's (Rudolf Schündler) lavish estate, depicting a dagger-wielding Black Queen and her bleeding sister, mirrors the relationship between Kitty (Barbara Bouchet) and Eveline. When Tobias dies 14 years later, he bequeaths property and immense wealth to his children, to be split evenly. However, his will stipulates that his heirs must wait one calendar year before cashing in their inheritance. It is his hope from beyond the grave that Eveline and Kitty will not suffer the same fate as those who came before, as his death marks the 100th anniversary of the urban legend. As the final film of Miraglia's career, "The Red Queen Kills Seven Times" is the murder mystery to end all murder mysteries.

The House with Laughing Windows

A Giallo by default, there are far fewer murders in "The House with Laughing Windows" than one might expect. Writer-director Pupi Avati supplies his 1976 film with a sensual sheen, almost otherworldly and displaced from any tangible truth. With an unreliable narrator that'll leave you questioning the story every step of the way, the Lino Capolicchio-starring feature depicts Stefano's arrival in a secluded, lagoon-side village. He's taken a job to restore a precious, albeit graphic, fresco portraying the sacrifice of St. Sebastian.

The painting's creator, a local artist named Legnani, went mad — or that's how the legend goes. But perhaps there's something far more sinister at play. As Stefano follows a series of clues that link back to the painting, he takes up residence in the same villa Legnani once called home, where the artist unceremoniously lost his mind. Rapidly, Stefano's world flips upside down, and he careens directly into the mouth of madness himself. While the film follows some traditional narrative beats and is etched with classic Giallo hallmarks, nothing will prepare you for one of the wackiest finales of all time.

The House by the Cemetery

"The House by the Cemetery" bookends Lucio Fulci's Gothic-horror trio, arriving in 1981 after "City of the Living Dead" and "The Beyond." Unlike those previous works, "The House by the Cemetery" appears like a ghost in the night, rattling poetically and poignantly about an unfulfilled existence and finding peace in the afterlife. Screenplay co-writer Dardano Sacchetti reportedly drew upon Henry James' novella "The Turn of the Screw," while Fulci sought to write a story that would easily fit into H. P. Lovecraft's spooky universe.

Norman Boyle (Paolo Malco) moves his wife Lucy (Catriona MacColl) and son Bob (Giovanni Frezza) into Oak Mansion, which was once owned by his mentor, the late Dr. Peterson, and determines to continue researching old, abandoned estates. Despite a warning that Bob receives from a ghost girl named Mae (Silvia Collatina), who haunts the property, the cozy little family settles into their new life. But things turn sour and they soon come under siege by a horde of oozing rotters. Fulci delivers a much more nuanced ghost story, framing themes of death, sorrow, and acceptance around bumps in the night and skin-chomping freaks.

Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key

Another Sergio Martino classic, "Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key" (1972) wins not only the award for best title ever but for its genius reapplication of Edgar Allan's 1843 poem "The Black Cat." Perennially used in countless other horror films, including 1934's "The Back Cat" with Bela Lugosi and Lucio Fulci's 1981 feature of the same name, a black cat is the key to unlocking this film's mystery.

Luigi Pistilli plays alcoholic abuser Oliviero Rouvigny, a once prolific author. His disheveled, mistreated wife, Irine (Anita Strindberg, star of other Giallo staples like "A Lizard in Woman's Skin"), has had enough of her husband's wandering eye and begins a love affair of her very own (with the person you'd least expect). When his mistress is hacked to bits, Oliviero naturally becomes the prime suspect, and must convince the authorities, as well as his wife, of his innocence. Even Irine's furry feline companion named Satan isn't too keen on him, often snarling at him.

"Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key" is a ball of yarn, its single thread a tattered and frayed means to a gloriously bonkers end. Misdirects bat the viewer around for most of the runtime, and as you vault into the third act, the killer's shocking identity is revealed with a purr and a hiss.

Deep Red

Many, including /Film, have proclaimed "Deep Red" as Dario Argento's finest hour. And for good reason. The 1975 film expertly defines what a Giallo should be, stretched like elastic with its overly complicated plot points, character arcs, and obscene gore. In the aftermath of a psychic's murder, jazz pianist Marcus Daly (David Hemmings), who witnessed the murder from the street below, stumbles into a figurative maze, alongside skilled reporter Gianna Brezzi, played by Daria Nicolodi in a star-making performance. You may think you know who committed the crime, but you'd be dead wrong (perhaps literally).

"Deep Red" entrances you with clever camera angles, particularly when revisited from a different perspective. That's the magic of Argento's playfulness. He gives you the entire reveal in the process of telling the story, but you don't realize that you already know what happens until the very end. Images of children's playthings, such as dolls, evoke a sense of whimsy and innocence while impressing the emotional urgency of the proceedings upon the viewer. A bloody, hanging doll is especially troubling, but not nearly as unnerving as the buck-toothed ventriloquist dummy. That's just pure nightmare fuel.

Death Walks on High Heels

Diamonds are not a girl's best friend. Luciano Ercoli's 1971 film "Death Walks on High Heels" marries Giallo conventions with a jewelry heist. When her father is murdered on a train, French stripper Nicole Rochard (Susan Scott) worries that his death might have been the work of a looter searching for a million dollars in diamonds. Well, her instincts are right. Soon after, a masked burglar stalks her apartment, and she receives a threatening phone call from a killer using a voice changer, demanding the location of the diamonds. She knows nothing — or so she claims — and makes a getaway to the London countryside with Dr. Robert Matthews (Frank Wolff) in the hopes of avoiding becoming the next victim.

Danger follows, as does a trail of bodies. Ercoli centers Nicole's desperation in the hurricane's eye, building the story with a smart, acrobatic balance between a crime thriller and a soapy drama. The killer inches closer and closer, each titillating layer crumbling under foot and revealing more moral rot underneath. It's only a matter of time, and Nicole knows it. Maybe she's a victim, or maybe she's part of a grander diabolic plot. Sleek and hypnotic, "Death Walks on High Heels" more than earns its heart-pounding finale.