This Genius Invention Made 2001: A Space Odyssey's Most Complex Scene Possible

When "2001: A Space Odyssey" hit theaters in 1968, it was unlike anything audiences had seen before, and not everyone took kindly to it. According to The Hollywood Reporter, actor Rock Hudson was overheard grumbling "What is this bullsh*t?" before he ducked out of a screening in L.A., while in New York, around 250 people walked out of the premiere. The film eventually became a box office success, partially helped by a new poster campaign describing it as "The Ultimate Trip," aimed squarely at the stoner crowd. One sequence in particular is pretty awesome while you're high, but we'll come to that in a minute.

Kubrick's grand scheme for "2001" was to create a cryptic, mostly non-verbal film that "hits the viewer at an inner level of consciousness, just as music does, or painting" (via ScrapsFromTheLoft). In that regard, he certainly delivered. Based on Arthur C. Clarke's novella, "The Sentinel," the film spans four million years of mankind's evolution, from our primitive ancestors to our first steps out into the cosmos, guided by a mysterious, highly advanced extraterrestrial intelligence. Both humbling and wondrous, it's a film that stands outside its genre and almost outside of cinema itself, as unfathomable and awe-inspiring as the vast backdrop of the universe it is set against.

It's a big film with big ideas, and it required some big special effects to make the concepts fly once up there on the big screen. It took Kubrick over $10 million and almost two and a half years to realize his vision, personally overseeing a team working on over 200 special effects scenes.

The team relied on everything from well-established techniques such as wirework and model work to good old-fashioned sleight of hand. For the trippy "Star Gate" sequence, however, a young special effects wizard created a technique never used before...

Kubrick Wanted Authenticity

Special effects in the '60s were incredibly primitive compared to what we're used to today, and computer generated imagery was still a long way off as Kubrick started putting his majestic sci-fi epic together. According to The New Yorker, it wasn't until "Westworld" in 1973 when the first CG effect in a live-action feature arrived, creating Yul Brynner's Predator-like robo-vision years before we would see a similar effect in James Cameron's "The Terminator."

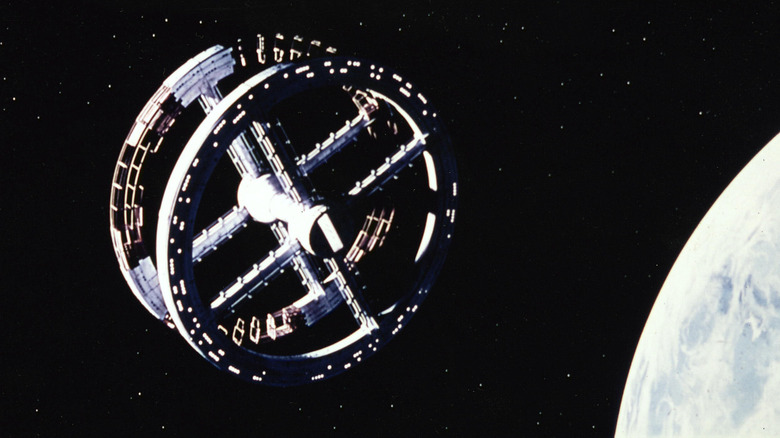

Kubrick was working a few years before Neil Armstrong took his one small step for mankind, but the director still aimed to create space travel and moon walk sequences that looked as realistic as possible. He didn't even have a full photo of the Earth from space to work with. ("The Blue Marble" was the first, captured by Apollo 17 the year before "Westworld" hit theaters.)

Coming out of the atomic era of silver rocket ships and bug-eyed monsters, sci-fi in the early '60s was very much mired in B-movie territory. Kubrick wanted to move away from all that, inspired by two educational films (via BFI): "Universe" from 1960, and "To the Moon and Beyond," which premiered at the 1965 New York World's Fair and screened in 360 Cinerama on a huge dome screen. The latter had such an effect on Kubrick that he hired the company who created it, Graphic Films, to work as design consultants on "2001." After Kubrick moved production to England and canceled the contract with Graphic, he flew one of their team over to the UK to help with the animated sequences – a young illustrator and airbrush artist named Douglas Trumbull.

In pursuit of authenticity, Kubrick also hired consultants who had worked with NASA and big players in the aerospace industry to help develop his spacecraft. These consultants were able to persuade the likes of Boeing, Bell Telephone, IBM, and Honeywell to provide hardware prototypes for free in exchange for product placement in the film.

Special Effects in 2001: A Space Odyssey

The "2001: A Space Odyssey" SFX team used a wide range of existing and cutting-edge techniques. It was one of the first films to make extensive use of front projection (via 2001 Archive), which gives a much sharper image than the corny old rear projection we're all familiar with – especially in driving scenes or, say, Roger Moore skiing away from goons down a mountainside.

As the technique's name suggests, an image is projected onto a screen from the front, and its most notable use in "2001" was in the "Dawn of Man" sequence. Outdoor scenes were thrown onto a huge 40 feet by 90 feet screen to create the illusion that our distant ancestors were really out there in the prehistoric wastelands, rather than a studio on the outskirts of London. Front projection was also used in some space sequences.

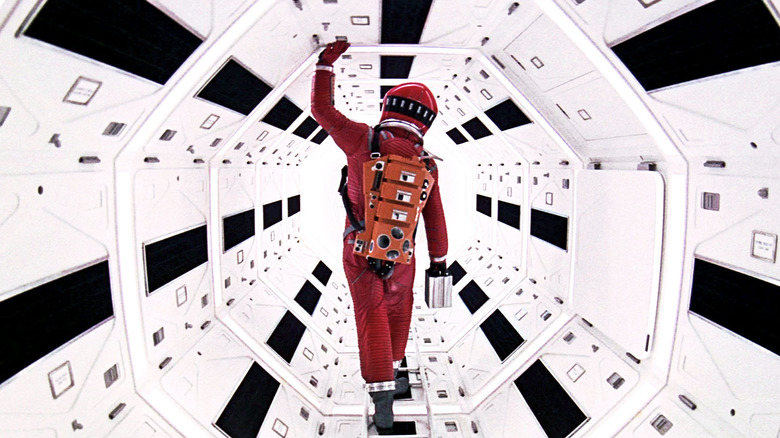

Other effects were just practical ingenuity and sleight of camerawork. For Discovery One's centrifuge, which creates artificial gravity for the astronauts on their long journey to Jupiter, a huge 30-ton "ferris wheel" was constructed at a cost of $750,000. With all the furniture and props bolted in place, the actor could walk along at the bottom while the set rotated. Meanwhile, the camera could be operated from a fixed location inside the wheel while the set rotated, creating the illusion that the astronaut was moving around the wheel.

All this was doable with existing tech at the time. Yet when it came to the Star Gate sequence, in which an astronaut travels to another part of the universe, Trumbull had to invent an entirely new approach.

Through the Star Gate

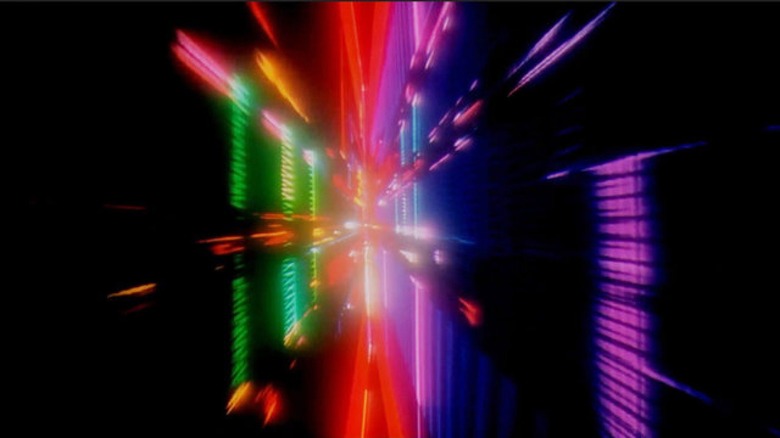

The screenplay gave Trumbull very little to work with conceptually, simply ending with the line:

"In a moment of time, too short to be measured, space turned and twisted upon itself."

Trumbull and the team tried a few things unsuccessfully, but then he was inspired by the work of John Whitney, the avant-garde animator who had worked with Saul Bass on the spiraling credit sequence for Alfred Hitchcock's "Vertigo." Adapting Whitney's technique, Trumbull came up with the "slit-scan" machine.

To create this machine, you need a stationary black surface with a slit cut into it. Behind the slit, you place a row of bright lights. Then you stick some psychedelic patterns to a large glass pane, which is moved on a track between the lights and the slit by a device called a worm screw. If, like me, you're having a little difficulty picturing this set-up, there is a great diagram at Space.com.

The camera is mounted on a second track facing the slit, also moved by a worm screw. The whole machine is controlled by motors and timers, modulating the movement of the panel of pretty colors and the camera. The camera slowly moves away from the slit, maintaining focus on the passing patterns with exposure set at one minute per frame. As Trumbell told The Film Stage:

"Kubrick was very enthusiastic about the results; he just said 'keep shooting, keep shooting.' It took four minutes a frame, so it was running twenty-four hours a day, and the stuff that is in the film was probably only about a quarter of what we produced. It was always aimed to be subjective. We tried some shots with the pod, what would be described as an over the shoulder shot, but it was clear it wasn't going to work..."

Once all these frames are tied together, the result is the hypnotic streaking effect we see in the Star Gate sequence. It's trippy stuff even now.