No Country For Old Men Ending Explained: You Can't Stop What's Coming

Ethan and Joel Coen tend to oscillate between making films about hapless law-breakers who get in over their heads and movies that cheekily subvert genre conventions (be they those of the gangster flick, screwball comedies, or Golden Age musicals). 2007's "No Country for Old Men" marked the rare occasion where the brothers directed a film based on a story they didn't come up with, instead adapting the 2005 neo-western novel of the same name by Cormac McCarthy. The union of the Pulitzer Prize-winning, punctuation-shunning American literary giant and the acclaimed oddball filmmakers was a fruitful one: "No Country for Old Men" took home many honors, including the Best Picture Oscar, and is still seen by many as one of the best movies of the 21st century.

Upon revisiting "No Country for Old Men" more recently, a few thoughts stuck in my mind — among them, Javier Bardem's haircut as the menacingly stoic hitman Anton Chigurh is still a perfect nightmare, the movie's handling of its Mexican supporting characters has only grown more uncomfortable over the years (I think everyone's more aware now of the Coens' poor track record when it comes to portraying anyone who isn't strictly a white U.S. citizen), and the film remains a masterfully crafted, well-acted work of suspenseful storytelling ... but is it really saying anything that profound or just waxing nihilistic, as McCarthy especially is often accused of doing?

First things first, though: let's take a look at the movie's actual plot.

(Don't) Take the Money and Run

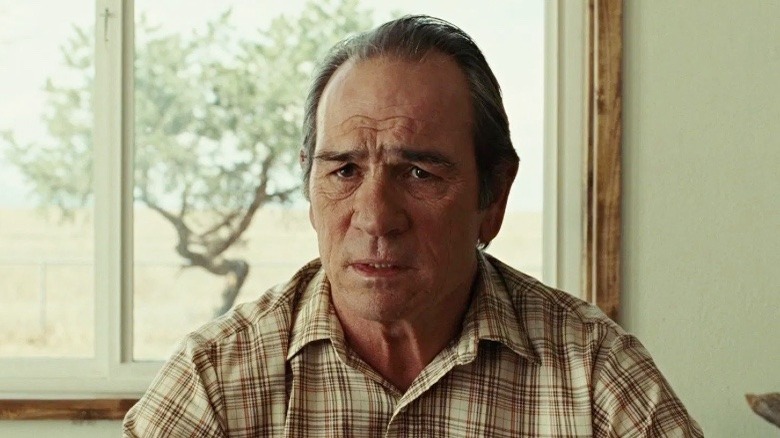

The 1980-set "No Country for Old Men" follows Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), a Texan welder who goes on the run after stumbling upon and stealing $2 million from a drug deal gone wrong. A proficient survivalist and Vietnam War veteran, Llewelyn finds himself hunted by Chigurh, a twisted killer-for-hire who wields a captive bolt pistol and occasionally gives his targets a chance to live if they can successfully call a coin toss. What's more, the pair are pursued by Texan Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), a world-weary, aging lawman who seems all-but resigned to always being one step behind his quarries.

In keeping with McCarthy and the Coens' track record of subverting genre tropes, Llewelyn is unexpectedly killed by a different group of criminals who've been chasing him before he and Chigurh can have their final showdown. Chigurh then manages to recover the cash and tracks down Llewelyn's wife, Carla Jean (Kelly Macdonald), having sworn to kill her if Llewelyn didn't surrender himself.

This is where "No Country for Old Men" deviates from its source material. In the novel, Chigurh offers the heartbroken, terrified Carla Jean his coin toss challenge, which she eventually accepts (and fails). However, in the movie, a quietly scared yet resolute Carla Jean refuses to play his sick game and, when he demands she "Call it," retorts that he can blame chance or fate all he wants: it's Chigurh who will decide whether she lives or dies.

Who Is No Country For Old Men Really About?

Despite their differences, Chigurh kills Carla Jean in both versions of "No Country for Old Men" (although the movie only implies he did without showing it). Yet, Carla Jean's reaction to Chigurh's bleak philosophical outlook in the film speaks to a greater idea: that everyone who lives long enough will one day grow old and feel like the world is spinning out of control (even if it isn't). And while we can't choose the hand of cards that life deals us, we can choose how to play the hand we're dealt while being aware of the privileges we enjoy that others don't.

This is also why Bell fully emerges as the story's true protagonist after Llewelyn's death in the Coens' "No County for Old Men." By that point, Bell (who's in his late 50s) has spent most of the film talking about how overwhelmed he is by all the violence in the world — with Llewelyn's death and Chigurh's escape being the last straw that finally convinces him it's time to retire. All the same, it's Bell who could really stand to learn the lesson imparted by Carla Jean's confrontation with Chigurh. Bell's uncle Ellis even drives this point home during his conversation with his nephew towards the end of the movie, telling him:

"What you got ain't nothin' new. This country's hard on people. You can't stop what's coming. It ain't all waiting on you. That's vanity."

The Book vs. The Movie

The Coens' "No Country for Old Men" is quite faithful to McCarthy's novel. Sure, it removes some backstory details and a minor subplot involving a runaway teenager, but beyond that, the broader strokes are kept intact. That being said, Carla Jean's tweaked fate in the movie does a better job of driving home the message that, yes, we do have a say in how we react to the way life treats us. It similarly reframes the car accident Chigurh gets into after killing her in both the novel and film, with the latter suggesting it was less an ironic twist of fate and more a direct result of Chigurh being distracted by Carla Jean's last act of defiance. (Also, not wearing his seatbelt — buckle up out there, kids!)

To be fair, because McCarthy's "No Country for Old Men" includes Bell's internal ruminations at the start of every chapter, it's clearer earlier in the novel than in the movie that Bell is the story's real protagonist, not Llewelyn. Still, I prefer how the film ends with Bell telling his wife about the recent dreams he had involving his father, including one where he saw his dad ride ahead of him on horseback through a snowy mountain pass, knowing he would be waiting when Bell caught up. The last shot then shows him looking silently frightened but at least determined to face his mortality head-on. By McCarthy and the Coens' standards, that's a positively cheery conclusion.