15 '80s Thrillers You Definitely Need To See

In his conversations with Francois Truffaut, Alfred Hitchcock defined suspense as a bomb under a table that only the audience sees, with a timer that only the audience knows about. "In these conditions this same innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene," he said. "The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen." That participation, a suspense by helpless omniscience, is what makes thrillers thrill.

The 1980s were a banner age for knowing too much. Early thrillers churned in the lingering fallout of Vietnam; later ones trafficked in the constant threat of nuclear annihilation, never more than one bad microchip away. In between, the 24-hour news cycle shined a sensational light on the serial killers next door and the Satanic Panics one street over. It was all grist for the mill. The decade's biggest hits — "Fatal Attraction," "Jagged Edge," etc. — provided a lurid template for the erotic thrillers and courtroom dramas ahead, but those hardly scratch the surface. The following 15 films are the less famous, but no less worthwhile thrillers of the Reagan era.

Cutter's Way

In "Cutter's Way," there's the 1970s and the endless hangover on the other side. Through the lens of cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth, it's all rust. Survivors like Jeff Bridges' Bone and John Heard's Cutter move so little they might as well be growing their own.

There are no genuine feelings left post-Vietnam or Watergate, only familiar warmth. Aging hippie Bone cheats with Cutter's wife because she's around. Wounded veteran Cutter accepts it because they're all he has. The two finish each other's suicide threats. When Bone witnesses an oil magnate dump a body, Cutter fixates on it, and solving the case becomes their sainted crusade. After everything the rich did to their generation, somebody needs to pay. "Because it's never their a** that's on the line," snarls Cutter.

His paranoia, and Bone's concern, have aged like fine rotgut. Cutter's either seeing spots or more than any average American is supposed to. What makes director Ivan Passer's acrid neo-noir sting isn't the answer to that mystery — is he onto something? — but the question to the question — does it even matter?

Dead Calm

Open sea doesn't age. The primal fears that inspired Charles Williams to write this novel in 1963, Orson Welles to attempt its adaptation for years afterwards, and Australian genre royalty to finally do the job in 1989 are one and the same. The isolated tension of "Dead Calm" might as well be hermetically sealed.

Director Phillip Noyce and cinematographer Dean Semler keep the lonesome horizon over everyone's shoulder; the film's three lost souls have sailed clean off the end of the Earth. Naval officer Sam Neill takes wife Nicole Kidman on an extended voyage to reconnect after the death of their young son. Any interruption is too much interruption, and he immediately doubts the horror story of floating survivor Billy Zane. Before long, Neill is abandoned on Zane's sinking ship and Kidman is forced to fend off the new maniac onboard hers.

The juxtaposition between Zane's sparkling delirium and Neill's dwindling lung capacity nets two thrillers for the price of one. In the center of it all is Kidman, then just 20 years old, etching her star one harpoon at a time.

The Package

Gene Hackman asks the million-dollar question early on and earns every penny of it: "Hey, what the hell's going on?" His disgraced Master Sergeant is still not disgraced enough for his punishment: babysitting Tommy Lee Jones from a Berlin barracks to a Washington court martial. Hackman knows it's a bunk detail long before his prisoner gives him the choreographed slip.

He also knows exactly what kind of movie he's in. It's his overqualified intelligence, along with the matched wits of allies Joanna Cassidy and Dennis Franz, that keeps the motor running. "The Package" is batting practice for director Andrew Davis's eventual grand slam, "The Fugitive." The monochrome squalor of Chicago in winter. A righteous, resourceful man on the run, trying to clear his name before the cops — or worse — catch up to him. Jones crackling even off screen as the antagonist with better chemistry than most lovers.

But "The Package" is chillier by design. This conspiracy is too opaque for anyone to make out entirely. In political thrillers like these, even if the day is saved, there's always tomorrow.

52 Pick-Up

Part way through "52 Pick-Up," blackmailed contractor Roy Scheider does the unthinkable: He invites his blackmailer into his office, to sit at his desk and read his financials. The criminal in question — John Glover, all teeth and deep-Vs — obliges. The two sit politely in the dark and guess how far the other guy has overextended himself. "Like a lot of people who make a lot of money," the predator says of his prey, "you don't seem to have any."

It's one more miscalled shot in an already sloppy game of hardball. Like all Elmore Leonard crime stories, the beauty is in the unpredictably human zigs and zags. Thieves rob the wrong rich man. A cheating husband comes clean. Blackmail bluffs its way to murder. For all of Glover's charismatic depravity and Scheider's caught-in-the-cookie-jar rage, it's only in Ann-Margret's silence, as the politician's wife unwittingly sacrificed, that the pain settles in.

The author personally adapted the screenplay and director John Frankenheimer lets his trademark grit speak for itself — it's a different, darker beast, but "52 Pick-Up" belongs on the same shelf as later Leonard adaptations like "Jackie Brown" and "Out of Sight."

Dead of Winter

This is the kind of thriller where the audience sees the crank and hears "Pop Goes the Weasel" long before the hapless victims even notice there's a jack-in-the-box behind them. If you take any comfort in those cackles, then consider "Dead of Winter" a cable knit sweater.

Starving actress Mary Steenburgen lands the audition of a lifetime. For what? She's only half sure. But it involves a taped performance at the producer's upstate mansion, cut off from civilization by a blizzard and other, less natural obstacles. Before anyone can say "Cut," she finds herself trapped in a good ol' fashioned haunted house. Secret passages. Two-way mirrors. Panicked shadows behind stained glass. And there's just got to be something in the attic.

The outside world is a black-and-blue wasteland. Inside, director Arthur Penn, no stranger to the stage, leaves the theatrics theatrical. No threat is without a sneer, no scream without a delicately defensive hand. You might've seen these sights before, but it's still a cozy ride with good company.

Miracle Mile

A lonely man steps out of a phone booth as it rings. Thinking it might be the woman he couldn't reach, he answers. A stranger on the other end instead tells him that nuclear war will end civilization in a little over an hour. It sounds like the setup for a dark joke, but writer-director Steve De Jarnatt never allows a punchline.

Warner Bros. sat on the script for years in hopes De Jarnatt would rewrite it and make the apocalypse nothing more than a dream. No such luck for lovebirds Anthony Edwards and Mare Winningham, who have the serendipity to find each other on what may or may not be the last day of human history. Even if the call is a hoax, the chaos they accidentally cause in their efforts to warn the world is as real as an air raid siren.

The first half hour is a romantic comedy. Sprinkled across the rest are capsule dramas about desperate people making peace with the time they have left, be it 10 minutes or eternity. It's harsh and humane, cold and comforting. There's simply nothing else like "Miracle Mile," a paranoid love story with the biggest ticking time bomb imaginable.

Hopscotch

There are few purer cinematic pleasures than watching Walter Matthau be a little stinker. In "Hopscotch," he doesn't just get to drive Ned Beatty to attempted murder, he does it while playing basset-hound James Bond.

"You running? Me chasing you?" he asks an old KGB counterpart. "We'd look like Laurel and Hardy." Espionage is a stinker's business, after all, even if CIA chief Beatty mistakes it for something important. When Matthau is forced behind a desk, he liberates his old files and quits to write a tell-all memoir, emphasis on all. One mailed chapter at a time, Matthau taunts his former employers and drags them by the nose from one end of the globe to the other.

Defeat is never played lightly — one ruse sees the CIA wasting thousands of bullets on the thorn in its collective side — but also never in question. Matthau is Bugs Bunny. Beatty is Elmer Fudd. Only one of them understands the natural order of these things and it's not the one dangling out of a helicopter, hot pink with wrath, trying to take down a biplane with a pistol.

The Mighty Quinn

The magic of "The Mighty Quinn" is in the margins. The universal Caribbean environs. The lived-in ecosystem of layabouts, witches, and wealthy invaders. The music, so shopworn that the locals know the choruses by heart. This little universe seems like it sprang from a series of happy-go-lucky noirs, not just a single novel, "Finding Maubee," by Albert H.Z. Carr.

The miracle of "The Mighty Quinn," though, is why they changed the title. A full year before "Glory" announced the arrival of Denzel Washington the actor, this minted Denzel Washington the movie star. As the FBI-trained police chief Quinn, he's smart enough to know that a flash of his ice-cream smile can usually keep the peace. But even when the heat is on, and childhood friend Maubee — a puckish Robert Townsend — is suspected of murder, Quinn doesn't lose his cool. He just slinks to the nearest piano and wins back public opinion with a singalong.

Director Carl Schenkel knows the same tune. Whenever the plot makes too much noise, he lets the reggae soundtrack and island spirit drown it out. It always wins, just like Quinn.

Roadgames

The first trick in "Road Games" is right there in the name. Despite arriving in the Ozsploitation groundswell of "Mad Max" and releasing just six months shy of "The Road Warrior," it boasts precious little vehicular mayhem. Besides a trailered boat getting sideswiped into matchsticks, it's mostly open road and a killer who may or may not be driving in the same direction.

Director Richard Franklin, friends with Alfred Hitchcock since a college screening of "Rope," gave screenwriter Everett de Roche the script for "Rear Window." Eight days later, he got "Rear Window" on wheels, with Stacey Keach and Jamie Lee Curtis standing in for Jimmy Stewart and Grace Kelly. Together in the cab, they flirt, pet his dingo, and psychoanalyze their maniac — on the open road, pondering hypothetical murder is just another way to pass the time.

Given the film's vintage, Franklin shows more than Hitchcock ever did but not by much and never in a hurry. Anybody wondering how he landed the director's chair on "Psycho II," another must-see thriller, needs to play "Roadgames"; the proof is in the rear-view mirror.

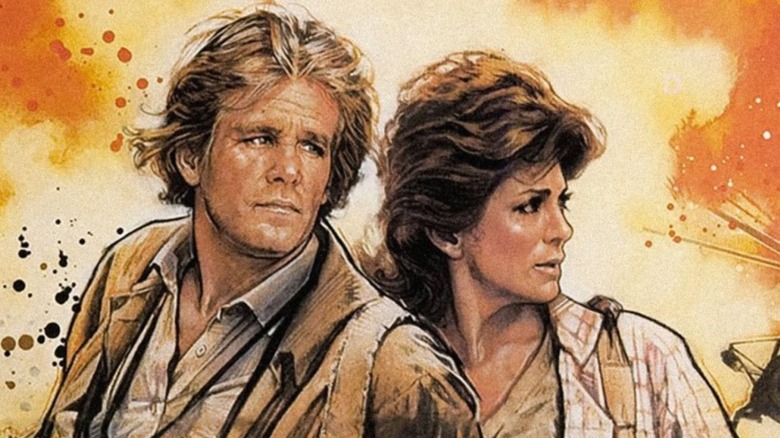

Under Fire

"I don't take sides," says photojournalist Nick Nolte, "I take pictures." In any other voice, that philosophy is thin enough to see through. Tumbled in Nolte's God's-honest gravel, it's bulletproof.

His latest no man's land, the closing seconds of the Nicaraguan Revolution, is lousy with other hangers-on believing what they need to. Fellow journalist Joanna Cassidy believes they're making a difference. Her old flame, anchor Gene Hackman, believes she and Nolte only shacked up after he left. Mercenary Ed Harris believes whatever the next regime pays him to believe. When Nolte finally, fatally forsakes his code and intervenes, it's enough to topple the whole house of cards and maybe, just maybe, what's left of the government.

Roger Spottiswoode's "Under Fire" is a tightrope act, not least because of the nonfictional bloodshed behind the love scenes. Lushly desolate photography from Kubrick DP John Alcott makes the Americans as alien as their sought glory is obvious. Anyone disappointed with their eventual yield should seek out Oliver Stone's "Salvador," a carnival-mirror reflection about a seedier foreign correspondent wiping the ideals out of his eyes.

The Mean Season

On his way to resign, burned-out reporter Kurt Russell stops off to bid Joe Pantoliano good morning and goodbye. His coworker barely notices, lost in the triplicate glow of TV screens. Two show the morning news. The third, "Tom & Jerry."

For frontliners like Russell, they're both the same vicious cycle. It's why he's gunning for a transfer to Colorado with schoolteacher wife Mariel Hemingway. He's done chasing the latest loon. Until, that is, the latest loon decides to chase him, calling the reluctant hero collect. But with all the sudden attention, just how reluctant is he?

The Miami Herald newsroom is a fluorescent purgatory where time both doesn't move and just ran out. Glory only arrives beneath pictures of dead people. "News gets made somewhere else," deadpans editor-in-chief Richard Masur. "We just sell it." Without caving into pulp, Director Phillip Borsos lays on the frustration thick and humid. Faces iridescent with sweat. Horizons choked bloodless ahead of a hurricane too routine to notice. And, finally, Lalo Schifrin's score taunting it all like a brass mosquito.

House of Games

Con artist Joe Mantegna tells psychiatrist Lindsay Crouse to hide a silver coin in one of her fists. Twice in a row, without hesitation, he guesses the guilty hand. How, she wonders. "You've got a tell." It's a brisk education in grift for her and a sly warning to the audience: If you're watching the silver coin, you've already lost.

In his directorial debut, playwright David Mamet makes a Three-card Monte game out of Russian nesting dolls, each choice not revealing victory or defeat but another, more intricate trick. As one of Mantegna's charming partners explains, "It's the American way." That's excuse enough for Crouse, an expert on addiction, to stick around and pay attention. Watching them work has the same verboten allure as hearing an off-duty magician let something slip — lucky that legendary card shark Ricky Jay is part of the team.

Mamet's words land with the rhythm of hard-thrown darts. Cinematographer Juan Ruiz Anchía breaks the dark only with poolhall lamps and all-night laundromats. "House of Games" is easy to fall for, whether or not you're watching the silver coin.

Cop

"Cop" is based on a James Ellroy novel called "Blood on the Moon." The change is a deceptive improvement. At least it gives the audience a fighting chance to get in on the joke early. There's a madman in the mix, but he doesn't matter, not to detective James Woods or director James B. Harris. This is a cop story, among the decade's most honest.

Lloyd Hopkins is a quick draw with his badge from turning it in so often. He cheats on his wife like it's an Olympic sport. His daughter stays up just to hear his latest bedtime story about a human rights violation. When a woman truly, deeply opens up to him, Hopkins summarizes her half-heard traumatic past as "the whole enchilada." He's the loose cannon taken to its sociopathic extreme.

Woods wears humanity like a cheap Halloween mask. In his glass eyes, all victims should know better and all criminals should die. For most of its runtime, "Cop" passes for a hard-R "Dirty Harry." Only in the final shot does Harris make it suddenly, violently clear what this really is: a serial killer procedural, one about the man holding a .44 Magnum.

The Bedroom Window

"The Bedroom Window" is an education in checks and balances. Young executive Steve Guttenberg is fooling around with Isabelle Huppert, the boss' wife. When she witnesses an attempted murder out his window, he testifies in her place to keep their affair secret. But then the police ask him to pick the attacker, a man he never saw, out of a lineup. But then the right perp ends up on trial. But then Guttenberg has to lie under oath. But then...

For every action there is an equal, opposite, and stomach-dropping reaction. Curtis Hanson, directing his own adaptation of an Ann Holden novel, gawks and glides at the material like a poor man's Hitchcock. Guttenberg, to his credit, plays a good poor man. His "Police Academy" sheen makes his repeated misfortunes that much more surprising, the class clown finally tried for his crimes. Even the would-be victim, Elizabeth McGovern, holds him accountable as they inevitably flirt. "Star Wars" DP Gilbert Taylor traps the lot in an anamorphic prison, warping every frame shut around them, leaving no way out but through. In smart, sexy thrillers like these, they never had any other choice.

The Ninth Configuration

Why would an astronaut refuse to go to the moon? It's an absurdist riddle on a good day. Posed within a crumbling fortress refashioned as a military mental hospital, it's enough to drive anyone mad.

Stacy Keach's Colonel Kane is transferred in specifically to make sure that madness is authentic. Given his new patients — one believes he's Superman, another teaches Shakespeare to shih tzus — it's a tall order. The astronaut in question, a gleefully belligerent Scott Wilson, gives him the most trouble. "Are you the one that makes the chicken?" he asks the Colonel right before hurling a chair across his office.

Though it doesn't talk like a thriller, "The Ninth Configuration" walks like one. Keach tiptoes around the Gothic sprawl like a man in a minefield of his own making. There's a mystery here, but not the stabbing kind. William Peter Blatty, adapting his own novel, called it "the mystery of goodness." The solution is both profound and prosaic, a fair paradox for a movie still fish-nor-fowled into genre obscurity. It's a thriller, a horror, a comedy, a drama, and a character study about crises of faith, all of them arresting.