Antlers Director Scott Cooper Keeps On Making Different Kinds Monster Movies [Interview]

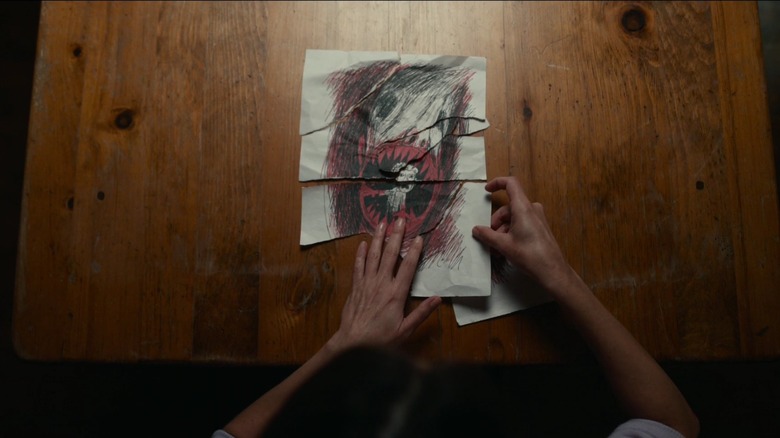

Filmmaker Scott Cooper's voice is loud and clear in "Antlers." It's a grim horror tale, based on "The Quiet Boy" by Nick Antosca and produced by Guillermo del Toro. Cooper's film is as much about addiction as it is about the presence of the wendigo. The director behind "Crazy Heart" and "Hostiles" brings his eye and taste for drama to the long-awaited "Antlers." As he said to us, "It works to some degree on levels, better than others."

It is a horror movie, like Cooper's other films, specifically aimed at adults, too. He makes big-budget dramas meant for the big screen. As he told us during a wide-ranging interview about "Antlers" and his previous films, he's fortunate whether people see them in theaters or, ideally, continue to revisit them.

"I'm also making a film in a genre which I've never made a film..."

You rewatched "Alien" a few times before making "Antlers." What did you takeaway from revisiting it?

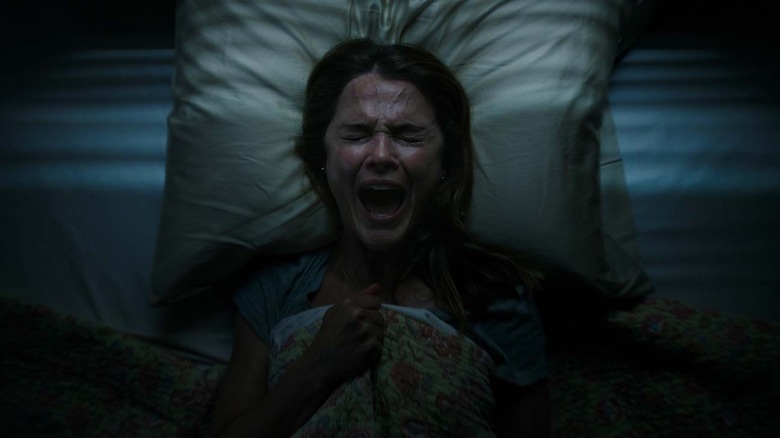

I think Ridley, who produced my second film, "Out of the Furnace," very masterfully created a science-fiction film, a classic horror film, but also a political film about how unimportant the working class is to whomever sent these folks out on to this mission. And then you have a heroine in Ripley, who is very strong, who's also compassionate and vulnerable. And that's really what I wanted with Keri Russell's character, Julia, those same qualities, which I think Keri performs beautifully. I also looked at William Friedkin's "The Exorcist," which deals with the supernatural and family grief, but is portrayed so realistically, that's what makes it so terrifying. I looked at Nicolas Roeg's "Don't Look Now," which also deals with family tragedy, as well as "The Shining." All of those deal with family and trauma and this supernatural and grounded experience, and which is precisely what "Antlers" is.

Like "Alien," how long did you want to wait to hold off on revealing the wendigo?

Yeah, that's always a struggle. There were a lot of challenges in this film using a practical wendigo, and then marrying it with a little bit of CGI, trying to marry my very grounded sensibilities with Guillermo Del Toros more whimsical and fantastical sensibilities. It's a miracle that any of it works because it's quite difficult to do. I'm also making a film in a genre which I've never made a film, so I'm not aware of all the pitfalls. I suspect in my self-serious way, trying to make a high-minded drama, but also a terrifying monster film. It works to some degree on levels, better than others.

The Whitey Bulger story could be classified as a monster movie.

Oh, no question. Whitey Bulger was a monster, Woody Harrelson in "Out of the Furnace" is a monster. Those are the things that scare me more than actual creatures. It's the humans that act in ways that are horrifying and terrifying, because I like to hold up this dark mirror to the fears and anxieties that we as Americans face every day. Jack, we're facing a lot of, man.

The opioid crisis weighs heavily on this movie.

Yeah. America is suffering an addiction crisis, and there are no two ways around that. Opioids, methamphetamines, alcoholism, and the pandemic only exacerbated that. There's a kind of a spiritual devastation that courses through many small towns that are left behind in America, who were once supported by a factory or a mine. And that closes and the whole fabric of that changes. Those are the stories that interest me, people who live on the margins because very often they aren't in major studio films.

"Christian Bale and Scott Cooper's rom-com."

"Crazy Heart," too, shows the horror and struggles of addiction. While a "horror movie" sounded different from you, did it also feel in your wheelhouse?

I'm glad you picked up on that because when Guillermo Del Toro approached me to write and direct this film, he said, "Scott, your last three films have been horror films and nobody knows it. Would you consider directing an actual horror film?" I said yes, because my early earliest film remembrances and experiences were in horror films. When I was with my older brother and I was too young to probably see these films and they still have an impact on me. I think Guillermo was right as are you in picking up some of the horrors in my earlier work. Christian Bale and I did discuss "Hostiles" as a horror film because of the inhumane treatment towards Native Americans, the horrors of Rosamund Pike, losing her entire family and the difficulties of living in the American west. This is all to say, Jack, that I need to try my hand at humor.

How about a romantic comedy?

Christian Bale and Scott Cooper's rom-com. We have discussed it.

On the subject of horror movies, you made a nod to a great one in "Out of the Furnace" with "Midnight Meat Train."

Well, because you say to yourself, what's a movie that would get Woody Harrelson character out to the drive-in? He sees that title, and he's like, "I'm there." I mean, he's not going to be seeing Nicolas Roeg's "Don't Look Now," right? He'll see "Midnight Meat Train."

"Antlers" is also the first movie you've shot digitally. How was that experience?

It was very different. I had quite a few lab issues developing the film on "Hostiles." When you're shooting up in very high elevations, in very difficult weather and you're dealing with torrential rains and lightning and rattlesnakes, and floods, and air, and you're trying to make a road movie and then the lab doesn't develop it as they're meant to, that can be very trying on your spirit. Then you have to re-shoot scenes.

After four movies in a row shooting film, Guillermo said to me, "Once you shoot digital, Scott, you'll never go back to film." I used a very large format camera, which at the time was in its early infancy, the Sony Venice, which is like a 65 millimeter large format, because I wanted to put this young boy Lucas in a very big frame. Small boy, big problems, which is best experienced on a big screen, as opposed to seeing it at home to get that effect. Also, because I had two children, it's just easier. I didn't have as much time to shoot. You days are shorter. Our cinematographer, Florian Hoffmeister, he shot it beautifully.

Will you not be going back to film after this experience?

Well, I'm about a month away from shooting my next movie with Christian Bale for our third together and I'm shooting digitally.

"I just think you have to be careful when you're making films."

How else did you and Florian want to create atmosphere in "Antlers"?

Well, my young daughters are interested in film and I always see them playing around with their iPhones. If they're making films, they're always moving the camera. When I asked them, why are you moving the camera? They can't give me a good answer. And if you look at the masters or at least the ones that I really respect, Coppola, Kurosawa, Michael Haneke, these directors move the camera when it's motivated and they tell the story with movement. If you're moving your camera all the time, I tell my kids, when does it mean something? If you're telling the story with camera and move the camera, it will signify to the audience that this is why you're moving it. It will accentuate a certain emotion that you want to convey.

In directing this film, I wanted it to feel very composed, very classical, so that you didn't feel the hand of the photographer or Scott Cooper's hand, but what you were most paying attention to is the trauma that these characters are dealing with, the spiritual depth and devastation of the small town. I like to use landscape as another character. Landscape and how it affects the characters should tell you about as much as anything a screenplay or performance can.

So for me, it's about composition, how I move the camera, I try to whittle my dialogue to the core. The less dialogue, the better. If I can just make silent films, I would. That certainly doesn't satisfy a lot of people who I think are accustomed to only watching television and it's close up, close up, dialogue, dialogue, close up, close up. I just think you have to be careful when you're making films.

When you first showed your assembly cut to Guillermo, he said, "This is a Scott Cooper movie." How does that first cut he saw compare to what we're seeing in theaters?

Well, it's different. At the end of the day, the studio feels like what we're making is a horror film, we're making a monster film. I think the difficulty was reconciling my sensibilities with that notion. If you look at my body of work, it's more of a slow burn, longer, much deeper character development. There are always scenes that you trim, and in retrospect, you wish you hadn't, but that's the nature of a collaborative art form. I guess if I wanted to work in a less collaborative art form, I would just be a sculptor. But it's always a learning lesson with each film. I think, Jack, that the great danger is in doing safe work and I want to be pushed into uncomfortable spaces every time. Otherwise, I would just continue to make the same film over and over. What fun is that for the audience or for me?

You also make movies that are getting increasingly more difficult to make.

I'm incredibly fortunate. I hate to say it, but I've had less difficultly in getting my films made than a lot of filmmakers that I admire. I write for particular actors, whether writing for Jeff Bridges, specifically tailoring "Black Mass" to Johnny, writing three films for Christian Bale, and writing specifically for Jesse Plemons for this film. That makes it easier when you have certain movie stars who are starring in your films, but my movies don't let the audience off the hook and I don't sand down the edges.

I'm thankful that I have support like Searchlight among the best filmmakers in our industry, Guillermo, I had Ridley and Tony Scott produce "Out of the Furnace," the great Robert Duvall, who's a wonderful director, and obviously one of our great screen actors, produce "Crazy Heart." It helps when you bring together a package of that kind of talent, those actors and producers with their legacy. I'm just thankful that people still want to come see my films and allow me to make them.

"If everybody likes your movie, it's likely not very good."

You're not a fan of message movies. For you, where's the line between a message movie and a movie with something to say?

It's a tough line because some people will say that something is very subtly offered and other people will feel that it's none too subtle. It's subjective. I try to make it as subtle as possible, which is why, if you watch a film of mine a couple of times, those themes might become more pronounced. For me, it's about character first and then honesty and truthfulness. I really believe, Jack, that if I can see myself in my work, others will see themselves. I only make films that I want to go out and see on a Friday night. I will also say that a very legendary American director who has been a supporter of mine once said, "Scott, if everybody likes your movie, it's likely not very good."

My intent isn't to make divisive films. My films are made with intent and some social commentary that speaks to the times in which I live. I'm just holding up this dark mirror to the fears and anxieties, like I said, that we're all living with and there are a lot of them. I'm sure that there are lighter pastures ahead for me, for sure, as I continue to grow as a filmmaker. But if you don't take big risks, Jack, I'm not sure why you're a filmmaker in the first place.

You tend to shoot multiple endings, as you did with "Out of the Furnace," that could suggest very different meanings. Did you have alternate endings for "Antlers"?

No. I always wanted this to end the way that it did, not as a spoiler alert, with Jesse Plemons character. We understand from the beginning of the film that he is, we don't quite say that he's addicted to drugs, but we understand that he relies upon them. And then, we see him midway in the film and we understand that he's had very close contact with his wendigo. So, you might see where this is headed. But what I really like to do is, I like to have quite a bit of ambiguity in my films because I like to pose questions for the audience to answer themselves, because I believe that if you de-mystify everything and you give the audience too much information, that is not the key to a successful story.

How about your work with the First Nations consultants on this film? What questions did you have for them?

Well, Native Americans and First Nations, the issues they face and have struggled with for 400 years now are of great concern to me. I touched on some of those in "Hostiles" where you have Christian Bale, who's a very hardened US army captain who was essentially, as they would say, groomed to kill as they would call them "Indians," Native Americans. But over the course of that journey, does he understand how empathetic and sympathetic they are and what we've done to them as a nation? Chris Eyre, who's a great native filmmaker, great filmmaker in general, directed "Smoke Signals." He and the Northern Cheyenne were my advisors on "Hostiles." I wanted that to carry over into this film because here you have a white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant who's yet again, telling a native or indigenous story.

Chris Eyre was also helpful again, but then I turned to professor Grace Dillon, who teaches at Portland State University. She is the foremost authority on the wendigo. We talked about the wendigo can manifest itself in many ways. It's first and foremost, a spirit. It doesn't have to be a creature or a God or a monster. It can serve as a metaphor for addiction, abuse, spiritual decay, the pain and misery that lives in all of us that eventually will escape, the desecration of natural resources, the desecration of our bodies. She said it takes form in all of those. So, for people then who might see this film who aren't understanding of that, might write about what the wendigo refers to, does it refer to too many things? Well, then they haven't done their homework, like I have, and have people who have lived it and who've studied it, inform every decision that went into making the script.

"It completely changed my life."

In Jeff Bridges' book, "The Dude and the Zen Master," he talks about how on every set, he joins hands with all the crew and speaks a few encouraging words. Did he do the same on "Crazy Heart?"

He did. Firstly, let me just say, I wrote "Crazy Heart" for Jeff Bridges. When he said yes and made the film, it completely changed my life. Jeff means more to me than almost anyone in this industry. I'm still very, very close with him. One of the tenants to Jeff's success as a human is he spreads love and joy, especially in very cynical times in which we live. He does do that. It permeates the entire set and it sets a tone of love and compassion and sympathy and vulnerability that I think courses through that movie. I'm a better man for having worked with Jeff Bridges.

Why did you write it with him in mind?

I had been traveling around with the great Merle Haggard and, and I wanted that character to feel like Merle Haggard, Waylon Jennings, and Kris Kristofferson. I thought who better to embody all of that than Jeff Bridges, who also happens to be an excellent musician. And then, I brought T Bone Burnett on to create the music. And he and Jeff are close friends. I didn't realize that. It made for a very harmonious process, but Jeff, everything you're seeing, he's playing and he's singing. I think the film also reawakened his desire to be a musician, because he's traveled for years now since then. He's touring singing "Crazy Heart" songs and some other ones that he's written. It's a facet of his life that many people weren't aware of that I was just happy to capture on screen.

How did working with Sam Shepard on "Out of the Furnace" change you as a writer?

I mean, what young actor or writer in America doesn't admire Sam Shepherd? Talk about not letting the audience off the hook or sanding down the edges, but really looking at a very searing portrait of American family life or American life in general. When I wrote "Out of the Furnace" and I sent it off to Sam, because I had him specifically in mind, as I did Christian Bale, I got a call that Sam was going to call me. The first thing he said was, "You had me at the title, one of the best titles of a film that I've read in a long time."

We became very close and we talked about his writing process and how he, somewhat akin to me, puts the issues that he's grappling with into his writing and what it means to be a father, but also to be an artist, what it means to talk about the country in which you live and not be afraid to pull back the sheets, to show that we live in a very difficult country, one that is soaked in blood and tragedy, and that was founded upon genocide and slavery. You can't be afraid to shine a light on those tough subject matters. I learned that from Sam and then, of course, I dedicated "Hostiles" to him because he died when I was shooting that film. He loved that script and was very helpful. I would always share screenplays with him and we grew quite close, so he's great loss for me and many.

"People will find your film."

Writing for actors like Christian Bale, he's someone was such a large toolbox of skills. Specifically, how do you write for him then?

Christian has become my closest pal. We spend a lot of time together offsets whether I'm making another film or he is, our families traveled together. I confide in him. He's truly like a real brother to me. I see a version of Christian that many people don't see, and I write for that version. Someone who's incredibly compassionate and intelligent, but who feels deeply, who loves his family, who loves his adopted country flaws and all. Quite frankly, Christian is one of the people who, like Jeff Bridges, has this real ability to find the best in everybody. I think that's an incredibly admirable trait.

He works often with me or David O.Russell, Adam McKay, and a few other directors. We all get something very different from Christian, but I try to write from a very internal place tapping into all of the things that I know make him the incredible man that he is and somebody with a very rich, rich interior life. I have to say, Christian reads all my scripts whether he's in them or not and sees my early cuts. I thanked him for "Antlers." He makes me a better filmmaker.

A very funny guy, too.

Incredibly funny. People don't know that. He is incredibly funny.

Have you and Christian Bale seriously discussed making a comedy together?

Yeah, we have discussed it. And quite frankly, some of my friends who were very, very well-known comic actors are much more intense in real life and Christian's very playful but intense on screen when he needs to be. With Christian, my hope is that we get to make far more movies than just the three that we're making, because he has so much range and we both have such similar sensibilities and comedy is something that we love. So, who knows, Jack? It may happen.

After "Out of the Furnace," you told your biggest story with "Black Mass." There were so many characters, years, and stories to cover. How'd you try to distill it down to the essentials?

In retrospect, when I was making "Black Mass," a limited series just started to become in vogue. That's a story that's probably best told over limited series of six or eight hour timeframe, because the story is so rich and covers so much territory and ground. Trying to tell that story in two hours was incredibly difficult, but I was thrilled that I was able to tap into a version of Johnny Depp that I thought was terrifying, that I thought was also very human, but also it was a little bit like a cobra, someone who can be very, very still, and you have no idea when he's going to strike. You don't hear it. And then, he just strikes.

Watching a lot of the footage of FBI footage that I was supplied of Whitey Bulger, I mean, Johnny captured him perfectly. So many people were still around who knew Whitey as we were shooting in Boston, and they couldn't believe how closely he really captured who Whitey really was, as well as Joel Edgerton and the moral complexity of his character. Shooting in Boston in many of the locations in which those murders events took place infused the production and an authenticity that I could have only dreamt up.

"Hostiles" was another ambitious film. It's only been a few years, but how do you look back at it?

Well, it was really pleasurable because I think what you see is the film that Christian and I set out to make, whether you call a revisionist Western or a horror film, I'm just trying to look at a man who is conditioned to think one way, then over the course of a journey, you see him start to soften and understand the true horrors of what it means to be an American. That was incredibly difficult film to make, but I'll never forget that the first time that I screened that for an audience was in a Telluride at the film festival and the audience responded in ways I could have only dreamed of.

I was walking to the stage, for a question and answer session, the first person to greet me whom I'd never met, he was the documentarian, the great filmmaker, Ken Burns. With tears in his eyes, he hugged me and he said, "You did in two hours what I tried to do in 20 with my story of Vietnam. Scott, I think it's one of the best films in the last 25 years." We've become friends since then and other directors that I admire love it. People eventually find their ways to these films. I think that's the great thing about streaming services or certainly cinemas. Eventually, people will find your film, and over the course of many viewings, hopefully, the film becomes richer and deeper.

"Antlers" hits theaters on October 29, 2021.