David Fincher's Protagonists Ranked Worst To Best

Since 1992, David Fincher has constructed a signature style out of hefty, character-driven thrillers. Fincher's TV shows are just as heady as his films, too, with protagonists that aren't typical heroes, but flawed people. In fact, that theme even extends to his music video work, with his 1990 video for Aerosmith's "Janie's Got a Gun" foretelling the kind of director Fincher was destined to be. Thus, it's the characters who shape the core of a Fincher film; the settings are just window dressing for the humans to play in as they reveal themselves to us.

With a total of 11 feature films on his resume and a possibility that Fincher will come back for some more serial killer monstrosities in his Netflix series, "Mindhunter," it's a good time to take a close look at Fincher's big-screen protagonists. We're ranking these characters from worst to best, but it's not about how good their movie is. It's a look at the people themselves, a moral snap decision about whether they should be trusted to babysit our pets or watch our purse. With David Fincher, the most common answer is, no, we probably shouldn't — but they'd all take Poochie on one heck of a ride.

11. Mark Zuckerberg — The Social Network

It's risky to call this fictionalized version of a still-living billionaire David Fincher's worst protagonist, but the context of the film itself makes this an easy choice. "The Social Network" opens with Zuckerberg at the finale of his relationship with fellow college kid Erica Albright. Erica gives him a thesis-level read of his flaws, ending with an explanation of why he'll never be socially successful. It's not because he's a nerd, she tells him, but because, to politely rephrase, he sucks as a human being.

"The Social Network" isn't a documentary and we can't take its portrayals as fact. Jesse Eisenberg is playing an exaggerated version of Zuckerberg, taken from an Aaron Sorkin screenplay — Sorkin's scripts are already heightened enough to be classified as orbital satellites — and adapted from the book "The Accidental Billionaires," whose author never spoke with Zuckerberg.

The film itself isn't about Mark Zuckerberg as a person, although the camera only occasionally moves from his side. Our fictional Mark is a plot popsicle, a man that seems to unfeelingly move from incident to incident while writing the future of the internet. But this Mark secretly cares a lot. He's vengeful and needy, and deep down the story of his own social network is about how he's trying to use money and data to make people like him. It doesn't work, and it'll never work, and this Mark is fated to be powerful but also eternally alone.

10. Amy and Nick Dunne — Gone Girl

We love to see a couple that's suited to each other, and by the end of "Gone Girl," that's the Dunne family in a nutshell — whether they like it or not. Nick is an emotionally distant cheater who let his relationship with Amy dissolve along with their finances. Amy lives in the shadow of an idealized version of herself, trapped by the Amazing Amy persona her family built a fortune off of and the restrictions of a Cool Girl identity meant to please men.

"Gone Girl" is Fincher's parallel to "Fight Club," taking the audience inside a big screen rarity. Amy is a fictional woman who is allowed to thrash around in women's darkest, ugliest revenge fantasies. There's nothing lovable or redeemable about her — and, bonus, her husband is just as big a walking garbage disposal as she is. That's the point. They're deliberately terrible people, and Fincher and Gillian Flynn are giddy about showing us how awful they can be.

For Amy, whose desires drive the plot, their relationship is about style, not substance. It doesn't matter if she and Nick are actually keeping up with the trends, so long as it looks like they are. Sincerity is an afterthought, as it has been all her life. She knows all about the concept of persona, and as long as Nick plays along, she's content to keep wearing the mask. It's not a happy life, but by the time Amy's plot finishes unravelling, it's the one they both deserve.

9. Herman Mankiewicz — Mank

After a while, we start to get the sense that Fincher finds terrible people too fascinating to pass up. He might have a point, especially when the results are as riveting as Gary Oldman's turn as the man who wrote "Citizen Kane." Another fictionalized biopic, "Mank" visits screenwriter and critic Herman Mankiewicz at the nadir of his career. Mank might be about to turn in the script of the century, but his life is such a mess that the impact Orson Welles is about to make doesn't mean the same to Mank as it will to decades of film students.

It's confusing to realize how little of "Mank" is about "Citizen Kane." Instead, it visits with the rot hidden behind Hollywood's golden era, eyeing it all with a can't-quit-you cynicism. The film is as disjointed as memory itself. It's a fictional riff that leaves the whole movie as dreamlike as Mankiewicz's draft for "The Wizard of Oz."

Fincher's vision of Mankiewicz is like Milos Forman's "Amadeus" composer Salieri, both of them demonized by fiction to tell a tale about the moral decay that lurks inside of art. Both films mimic their time periods without truth; it's a cinema joke that the black and white "Mank" doesn't actually resemble an Orson Welles film. Meanwhile, Oldman's Mankiewicz is too self-destructive for art to save him. He's eaten alive from the inside, and although Mank has the last laugh in the movie's final scenes, in real life, he'll die a decade later. He's no one's idea of an uplifting figure, but damn if Herman couldn't tell a good story.

8. Benjamin Button — The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

Benjamin Button is as soft a protagonist as Fincher has ever offered. Brad Pitt is one of the best actors working today, with a vast range, but Button is a passive creature here. His magic-realism life passes in reverse, a discussion of the best and worst life can offer, with a switch in perspective to make it fresh. To be fair, "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button" was nominated for a basketful of awards, but the film doesn't hold up as satisfyingly as it could.

Pitt and Fincher do the best they can with a story that never held the timelessness its premise needs. Button was once a relatively obscure F. Scott Fitzgerald creation, and he can't hold a candle to Fitzgerald's other Jazz Age protagonists. Button can't shake off the glitzy dust of his home era, and his story offers a view of New Orleans that's always out of date. It lends the whole film a disjointed feeling, one that doesn't help when the film doesn't stick its landing. Is it all Button's story, or is it his lover's, Daisy? Button is passive and unreliable, and Daisy lives within his boundaries. It takes Hurricane Katrina to free her from having to recite someone else's story, one natural disaster to end another.

Button gets to have the last word, with a final sequence in which he drills down all the people he's known into a single descriptive line, all of whom seem to accept him with open arms. If that's Button's simplistic heaven, his reward for living a life in reverse, he can keep it.

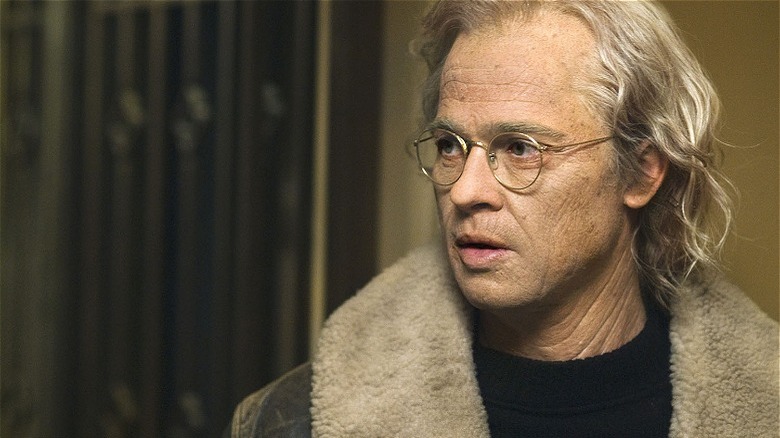

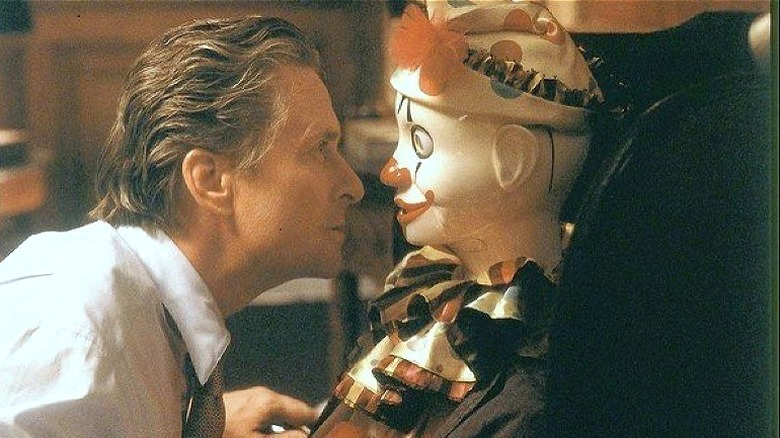

7. Nicholas van Orton — The Game

Michael Douglas seems like too nice a guy to play bastards so frequently, and Nicholas van Orton starts off as another self-centered and rich creature who's forgotten his basic humanity. For everyone that wanted to knock Gordon Gecko around after 1987's "Wall Street," David Fincher and "The Game" have us covered.

In van Orton's defense, his behavior comes from trauma. He's about to turn the same age that his father was when Papa van Orton killed himself. Nicholas saw it happen, and that might be why he's estranged himself from his loved ones. Despite the distance between them, Nicholas' brother, Conrad, sends him a gift card for a strange new game. Despite Conrad's intent, the corporation that runs the game rejects him. Or so Nicholas thinks.

Today we can recognize "The Game" as the world's biggest escape room, reliant on vague puzzles, psychodrama, and a lot of gaslighting. Despite the absolute horror it wreaks on van Orton's mental state, it works a treat. By the end of the game, Nicholas is ready to move on from his childhood trauma and make an effort at being a better person — probably after he sues the Game's creators to the moon and back.

6. The Narrator — Fight Club

The first strike against the narrator of Fincher's breakout movie is that he's only known as the Narrator. The second is that he's also an unreliable narrator. Third, he has the cheek to create an imaginary friend for himself with a cool name like Tyler Durden, and fourth, he made him look like Brad Pitt. The Narrator, or Edward Norton (since that's who he's played by), isn't the worst of Fincher's protagonists, but this is a man with some seriously heavy issues.

Narrator Norton enjoys a life of irony. He goes to therapy, but not to deal with his own problems. He's a rubbernecker to everyone else's misery, wallowing in his self-loathing. His relationship with Marla is so screwy that he has to bring in his Tyler Durden persona so that he can self-victimize. The Narrator can't compare to the hard, muscly dudeness of Tyler.

"Fight Club" is sometimes beloved by the wrong audience. The book is a poem about the dangers of toxic masculinity. The film, despite its understanding of Chuck Palahniuk's novel and Fincher's brilliant direction, became an anthem to a generation of aggrieved young men who thought fight clubs were good ideas. Narrator Norton, to his credit, lets go of Tyler Durden by the end of the movie. Others should, too.

5. Detective Mills and Somerset — Seven

David Fincher clearly loves working with Brad Pitt, and "Seven" gave Pitt his meatiest Fincher role. Detective Mills is just a bro at first, an eager street cop with only a vague interest in the subtleties of homicide investigation. Mills is shipped off to the city and paired with Morgan Freeman's Detective Somerset in time for one of the ugliest serial killer cases in modern fiction. Somerset is a throwback to the era of hard-boiled noir, an educated, detail-orientated man who both loves and loathes the world around him.

Neither detective can be judged without the other. The movie gives them a chance to learn from one another, changing both before their final showdown with the killer. Somerset's pessimism lets him survive the horror this case and its seven deadly sins wreaks, even re-invigorating his passion for his career in the closing minutes of the film. It's out of spite but it works, because Somerset learned to care again thanks to Mills and his small family. Mills turns out to be invested, able to change, and too passionate to endure the worst despair a man can face.

"Seven" ends with only one detective standing. But Somerset is now armed with the best lessons both men earned in their short and awful trial with John Doe. The city will be better for it, whether it deserves Somerset or not.

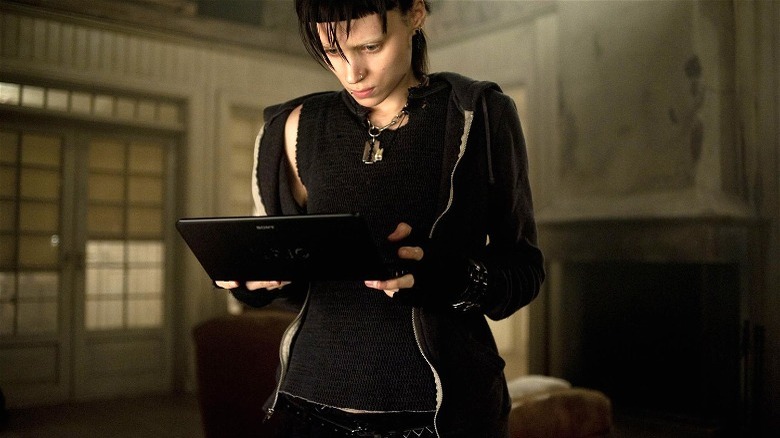

4. Lisbeth Salander — The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo

David Fincher and star Rooney Mara were faced with one of the movie industry's most treacherous hurdles, creating a feature film adaptation of a blockbuster novel when an excellent one already exists. It's a miracle that Fincher's 2011 adaptation of Stieg Larsson's "The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo" pulls it off, although how thoroughly seems to depend on whether or not the viewer prefers Noomi Rapace and her violently provocative take on Lisbeth over Mara's waifish presence.

Lisbeth Salander's greatest weakness as a character is her fictionality. Her vengeful drive could shift nations in the real world, resolving our questions about ethical social media and hidden bank accounts with a genius-level understanding of electronic security and a few well-placed explosives. Her role in exploring the trauma of sexual assault is difficult but sincere, and Fincher's film doesn't back away. The novel's original Swedish title is "Men Who Hate Women," and it's poignant that some discussions of the violence against Salander turn into the question of if Salander herself is sexist.

That this question is even asked underlines the need for Salander's burning rage. Some will always look for new ways to victimize people like Salander, who turned her terror into her armor, who turned her pain into a weapon, and who became a useful fantasy for survivors to empathize with. Like Amy Dunne, Lisbeth wouldn't exist without society's sexism. Fincher's film keeps Lisbeth someone to root for, even as she sometimes goes too far.

3. Meg Altman — Panic Room

David Fincher's 2002 thriller, "Panic Room," stars Jodie Foster as its protagonist, Meg. We could wrap this up right here. Jodie Foster is the queen of stable, sincere, and multi-layered protagonists. Even bad films have good Foster performances. "Panic Room" is almost boilerplate, an unusually straightforward Fincher film that spares most of its tension-inducing body blows for the homegrown terrors of a child in pain.

The film hinges on internal turmoil, with even the burglars terrorizing Meg and her daughter, Sarah, earning some psychological exploration. But the story is about Meg's determination, a mother's instinctive drive to protect her family pushed to the edge of destruction. Foster brings an undefinable weight to Meg; she's already endured a cheating husband and subsequent divorce. It's a too realistic cruelty that her new life starts off like this. It's equally powerful that her ex may have sucked, but his ex-wife and their daughter are important enough to him to immediately come to their aid.

No one is all one thing; cheating exes can still love their families, and robbers aren't just greedy crooks. Meg gets to display the same range. For all her strength, Meg's anger and terror also shine through. She's not perfect. She's frightened, and she can be spiteful. The reason she bought the brownstone with its fancy panic room is a parting shot over her divorce agreement. Meg could have been any one of us, but when played by Jodie Foster, she's also what we hope we would be in her situation.

2. Robert Graysmith — Zodiac

Robert Graysmith is another real world figure, although "Zodiac" lets Jake Gyllenhall reshape the cartoonist-turned-true-crime-devotee into a monument to dogged persistence. Graysmith is drawn to the mystery of the Zodiac Killer. His fascination with the riddle of the man underneath an executioner's hood is admirable to a fault, and that fault is the movie's point. Graysmith is a metaphor for being in too deep, but his wide-eyed leap into the world of true crime makes him an empathetic protagonist, and one of Fincher's best.

Graysmith is a daydreaming doodler at the San Francisco Chronicle when the Zodiac's letters start arriving. His own guesses about the killer go unheeded, and Paul Avery, the paper's police reporter, finds Graysmith as amusing as a puppy. But it's not all laughs for Graysmith, who can't avoid the impact that his obsession is having on those close to him.

Fincher's film portrays its murder scenes with a veracity that matches Graysmith's mania, yet the film is less about the Zodiac Killer than it is about the damage obsession can do. In its finale, Graysmith is as alone in the world as Arthur Leigh Allen, Graysmith's favored suspect. There's no catharsis when the two men meet, only silent assessment. Graysmith's faults are not on the same level as the Zodiac Killer's crimes, but they've nonetheless destroyed the life he could have had. Was it all worth it? There are no answers for Robert, but the audience can learn from his mistakes.

1. Ellen Ripley — Alien 3

Putting "Alien 3" at the top of any list that isn't titled "Top 10 Times a Director Got the Industry Shaft" is a wasabi-hot take, but the point we're making is that even in Fincher's torturous film debut, Sigourney Weaver is still one of the best actors around. Ripley's endurance and steel-spine determination is the film's star, and nothing, not the bad special effects nor Fincher's allegations of studio interference, can change that.

Fincher's burden is eased by Ripley's familiarity. The facts of her as a character remain unchanged, but the horror that shapes the prison planet she's stranded on lets Sigourney show new aspects of Ripley. She's human after all, touch-starved and grieving for the people that she tried to save. It's grotesque that "Alien 3" turns the hopeful ending of "Aliens" into a shaggy dog story, and the despair that clings to Ripley over the course of the film is depressingly relatable.

The "Assembly Cut" makes Fincher's intent with the film clearer, and its theme of war against an incarnation of violent sin becomes cohesive. The Xenomorph is Satan's dragon trapped in eternal war with Ripley. Ripley is both a Magdalena to the prisoners and motherly Mary to the lost. But there's no heaven to be won here, just a struggle in the prison's hellish pits. Ripley's determination wins, but at a cost. The toll on her soul is too much for her to carry, and as bleak as her dying scene is, there's a sense of relief, too. It's a performance that works, despite the movie's enormous flaws. Ellen Ripley is one of film's best protagonists for a reason, and she shines here.