Canary In A Coal Mine: How 'Us' Continues The Work Of Mark Twain And Rod Serling

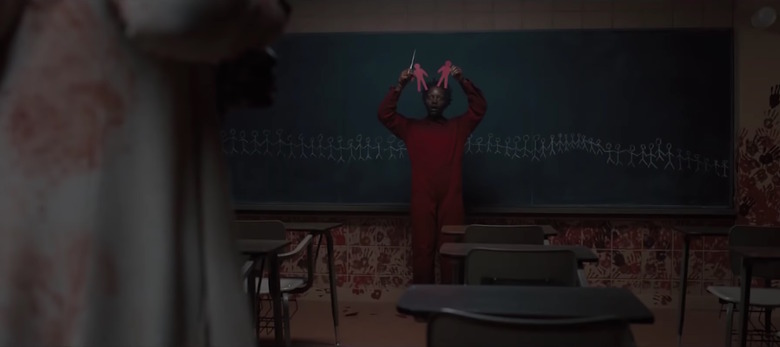

In the '60s, the author Kurt Vonnegut spoke about what he called the canary in the coal mine theory of the arts. In a speech to American Physical Society, he said, "This theory says that artists are useful to society because they are so sensitive. They are super-sensitive. They keel over like canaries in poison coal mines long before more robust types realize that there is any danger whatsoever."It's a useful prism to think about art that tries to tell us something and something I thought of often as I watched Jordan Peele's Us. Us is a movie with a lot to say. I wouldn't dare to presume that I knew what it was trying to say, or what underlying lesson Peele wanted me to learn for certain, but I can tell you what it told me. If you're reading this, I can presume you've seen Us. You know that it's about a world of shadowy "tethers" who are linked to us down below. You know that these reflections of us have nothing and are down below for reasons we can't begin to fathom. You know that the only thing these reflections want, at least one of them in particular, is a better life for themselves. When you throw in a healthy dose of horror and film's final twist, you have something that's equal parts Twilight Zone and Mark Twain.Spoilers for Us lie ahead.Watching the ending of the film unfold, I was struck by how much understanding enveloped me. Us had become a destination of a story that began with Mark Twain and followed its way along the tracks to Rod Serling. With most episodes of The Twilight Zone, Serling took the sort of social satire that Mark Twain had brought to the mainstream in the late 19th century and propelled it forward into the 20th. Between Get Out and Us, Jordan Peele has rapidly claimed the 21st century's station as his own (not to mention his own crack at The Twilight Zone itself.)Each of these three artists used science fiction and social satire to tell us something about ourselves, to hold a mirror up to society and say, "This is something we need to watch out for and you need me to tell you about it because others aren't seeing it."Let's trace this train of Us back, in hopes that we'll gain a better understanding of the film—and ourselves—that way.

Pudd’nhead Wilson

Pudd'nhead Wilson is a book from 1894, written by Mark Twain, the humanist humorist who also wrote (in case somehow you weren't aware) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. It would be easy to ignore the science-fiction element of Pudd'nhead Wilson today, but a central conceit of the novel is the use of fingerprints as forensic evidence. In the 19th century, this was, in fact, as much science fiction as a rocket to the moon, fantastical to readers. The book tells the tale of two people who could pass for twins, switched in their early days. One was the spoiled white child of a slave-owner and the other was the poor black child of a slave who could pass for white. The black child's mother was the nursemaid to both children and she wanted to make sure her son had the best chance at a good life, so she switched the children.Unfortunately, her biological son grew into a monster thanks to the nurturing of his new rich, racist family. Her adopted son, the actual son of these slave-owners, grew up to be kind and, sadly, settle into the life of a slave without complaint.This is not revealed until many years later after a murder in the small town happens. The fingerprints of the children that had been collected by Pudd'nhead Wilson, a young lawyer fascinated by the science, come into play and deliver the shocking truth to the town and they need to grapple with the idea that their notions of race and "nature vs. nurture" might be forever destroyed.It could easily pass for an episode of The Twilight Zone, couldn't it? And this is definitely one of the central ideas in Us, where you have these two women switched at birth and are forced into lives they would have never known otherwise. How does that affect their psyche? For the original Adelaide, it arrested her development and her plan is predicated on the whims of the child she was. Her tether, who assumes the role of Adelaide, becomes a real, thinking, feeling person because of the environment in which she's able to grow up.Both stories tell us something instructive about the inherent problems with different strata of classes and upward mobility, but with that audience-pleasing twist of social science fiction.

The Twilight Zone

In an interview with Rolling Stone, Jordan Peele mentioned that he'd been inspired by an episode of The Twilight Zone called "Mirror Image." This episode revolves around Vera Miles as she navigates a world where she becomes convinced that her doppelgänger is trying to replace her. Is it madness? Is it reality? The episode could be very easily taken as the anxiety of white people fearing their replacement by others and it makes a good show of it. That we're all struggling in our own ways and we're constantly stressed by the idea that we're on the verge of being replaced. So we all need to work harder and smarter and faster to keep that from happening.This particular Twilight Zone episode is much more metaphorical on this front, but Peele marries that idea together with the same spirit of social questioning that Mark Twain brought to his storytelling. Then, he wraps Twain-like humor with Serling-like terror and is able to give us something new.

Social Satire

Mark Twain tried to teach us that notions of racial superiority were absurd and illustrated that with Pudd'nhead Wilson. Sadly, he wasn't able to solve racism and privilege, but he certainly made a go of making more people understand it.Over his years on The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling tackled any number of issues from prejudice and bigotry to warnings about fascism and mob mentality. In the episode "The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street," Serling reminds us in his closing monologue, "The tools of conquest do not necessarily come with bombs and explosions and fallout. There are weapons that are simply thoughts, attitudes, prejudices, to be found only in the minds of men. For the record, prejudices can kill, and suspicion can destroy."But still, fascism and prejudice are both on the rise in the world and sometimes we seem powerless to stop it. But that didn't stop Serling from trying to do something about it.What do I think we can learn from Us? Plenty. The most acute lesson I might have drawn, though, was about economic inequality. If you make a person desperate enough for a better life, they're going to react to attain that better life. Violently if necessary. I mean, it's not hard to look at the rising economic equality in the United States and not see parallels to, say, the French Revolution. The revolutionaries in France didn't use golden scissors, though. They used guillotines. And how do we address that? Do we let it get so bad that violence is an answer? Or do we take that lesson and say, "Maybe we should fix this before we get to that point."Because why should any anxiety exist? Why should we allow a world where there is an underclass of people, living in the shadows, without the opportunities for advancement that we say we all deserve? Hands Across America was part of that notion of the American dream, of helping raise each other up. Unfortunately, Hands Across America failed as an experiment much the same way the American Dream has today for many. How can we become inspired by art like Us to fix that? Is that even possible?In his 1973 interview in Playboy, Vonnegut expanded on his idea about artists as canaries. "You know, coal miners used to take birds down into the mines with them to detect gas before men got sick. The artists certainly did that in the case of Vietnam. They chirped and keeled over. But it made no difference whatsoever. Nobody important cared. But I continue to think that artists—all artists—should be treasured as alarm systems."In this day and age Jordan Peele might be one of our finest alarm systems.But what good is an alarm system if we ignore it? Tracing the evolution of these stories, it makes me wonder what poison there is in our society that we've paid about as much attention to it as we do that car alarm blaring across the street. Racism. Bigotry. Fascism. Prejudice. Economic inequality. These things have been tackled by Twain and Serling over history and now, contemporaneously, by Jordan Peele.The lessons are there to be learned.The thing I love about political art is that it forces you to ask the question, "What are we going to do about it?"So I ask you that. What are we going to do about it?