Why The Time Is Right For "Screenlife" Movies Like 'Searching' And 'Unfriended'

Everything happens on the internet now, and that poses problems for filmmakers.For decades, movies and TV have struggled with how to depict the decidedly un-cinematic act of using computers. In the '80s, '90s and early 2000s, the typical approaches were to hype up the user interface with animation and 3D graphics, put the user in virtual reality, or make the computer talk. None of these were particularly realistic, and as the internet became more familiar to everyday people through the 2000s, movies had to change. We saw work that used floating, abstract graphics to depict phone or computer use. But these still suffered from the same inherent problem: how do you visually tell a story that takes place on a computer?Surprisingly, the answer seems to lie in the least expected place. What if audiences didn't need conventional filmmaking to be drawn into the story? What if the computer screen itself was enough? Enter a burgeoning new wave of cinema, consisting solely of recorded video from computer desktops.

A New Wave

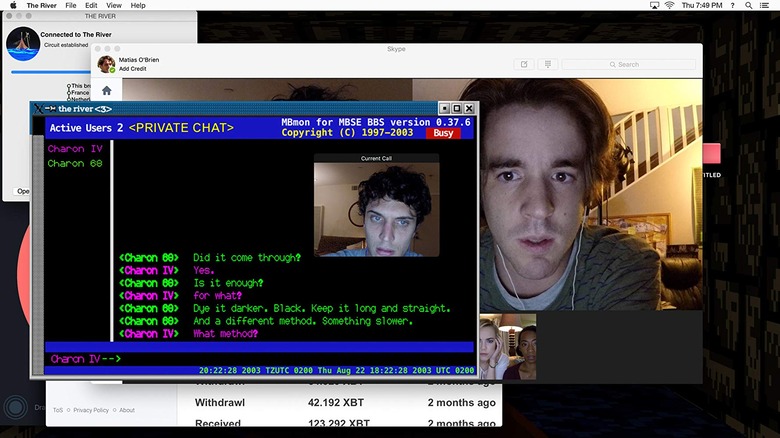

Dubbed "screenlife" by advocate Timur Bekmambetov (director of Night Watch, Day Watch, and Wanted), this new movement has already spawned several surprisingly great movies, and it's just getting started.Bekmambetov and his stable of directors didn't invent screenlife. Emerging from the language of found footage, early examples like The Den and Open Windows touched on similar techniques, but either minimised computer interaction, in favour of video capture, or heavily stylised it. It wasn't until Leo Gabriadze's horror film Cybernatural – later recut and retitled Unfriended – that screenlife started to find itself. It also found a patron, in the form of the highly successful Russian producer-director.Bekmambetov brought three screenlife films (Stephen Susco's Unfriended: Dark Web, Aneesh Chaganty's Searching, and his own Profile) and boundless enthusiasm to this year's Fantasia International Film Festival. He refers to screenlife not as a genre but as a visual language, like found footage or conventional montage-style editing, capable of sustaining genres inside it. Screenlife excites him because it's a new form of storytelling ripe for development, for discovery of new techniques. And he's right: based on the films shown at Fantasia, and Bekmambetov's passionate rhetoric, I've joined the pro-screenlife camp.Screenlife works because, frankly, we deal with computer screens all the damn time. We instinctively understand the meaning of everything on screen, and not just in terms of icons and terminology. A computer screen represents a character's subjective point of view, as well as their inner thoughts. The manner in which people move a mouse, or type, or arrange their desktop, or use apps, speaks volumes to a person's psyche. When somebody's typing, we're literally seeing them form thoughts in real-time – including editing or even censoring themselves. As a result, screenlife films can be extraordinarily intimate experiences.These movies are also, amazingly, a blast to watch with an audience. They wring enormous effect out of the tiniest actions, drawing us into their stories just like how we become absorbed in our own computing. Fantasia's trio of screenlife shows were among the best audience experiences I had in the three-week festival. They absolutely enthralled audiences, creating sadness, joy, comedy, tension, horror, and even empathy, in a way that felt genuinely new.

How It's Made

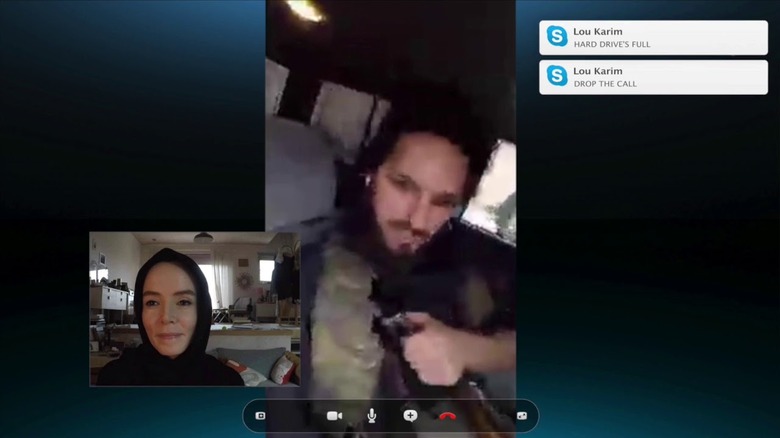

Screenlife films are jam-packed with storytelling, simply because there's so much information that can be displayed at once. That's exciting for filmmakers, but it doesn't come easily.All the traditional filmmaking disciplines come into play in screenlife. They're just deployed in a different manner to a conventional film, or even to animation. Scriptwriting functions as normal, except the action describes mouse movements, and there's possibility for peripheral writing in incidental social media posts, instant messages, and so on. Art direction determines what we see on the computer: the desktop layout, the images on someone's social feed, and even – in Searching's case – the operating system, which also helps to signpost different physical locations and time periods. Sound can be a combination of computer audio, ambience around the computer, or more expressionistic effects (although mouse clicks and typing sounds are more or less mandated). "Camerawork" can encompass many things, from webcam placement to the way the desktop is framed. With Profile, even casting was done entirely over Skype. But it's in performance, directing, and editing that things get super interesting.In developing the screenlife concept, Bekmambetov's team designed a specialised piece of screen-capture software that doesn't just record video, but code as well. A filmmaker can record a performance, then tweak it for timing, or even alter the onscreen images and text. In making Profile, much of which takes place over Skype between the UK and the Middle-East, Bekmambetov literally had actors Valene Kane and Shazad Latif Skype each other from those locations. What you see is the actor's performance – not just on camera, but in the use of the computer itself. Every interaction is real, an extension of the actor's body language and characterisation. Even their breathing becomes a crucial component – think of all the unconscious sounds you make when using computers.Each of the three films shown at Fantasia sported a vastly different approach to editing, representing a small portion of how much stylistic variation is possible. Unfriended: Dark Web takes place in real time, so it's pretty much an uninterrupted screen recording. Profile starts out as an uninterrupted recording, but pulls out to reveal we're watching a series of recordings stored on a different computer, with someone else scrolling through the different movie files and jumping nonlinearly through the timeline. Later on, the protagonist begin to edit her own recordings, which adds fascinating additional layers. Finally, Searching uses the most traditional editing style of the three, employing close-ups, zooms, and cuts to direct the audience's attention just as a conventional drama would.

What It's All About

Screenlife can support a wide variety of genres. Unfriended is a supernatural haunting thriller. Its more-grounded sequel deals with the dark web, secret Internet societies, and the intersection of online and real lives. Profile is a journalism thriller based on a true story (and even actual screen recordings), following a British female journalist catfishing an ISIS recruiter. And Searching is a family kidnapping drama, with John Cho as a father retracing his missing daughter's steps only to discover he never really knew her at all. There are even fringe examples: Adult Swim's short Final Deployment 4: Queen Battle Walkthrough uses Twitch let's-play streams to create surreal, existential comedy, while Cam combines live-action and screenlife techniques to tell a psychological horror story about sex work and identity.These films all feel vastly different. Unfriended had audiences screaming. Profile engages intellectually with politics. Searching moved me to tears. But despite that tonal diversity, the stories they tell revolve around a common theme.That theme, of course, is the place where we spend a huge portion of our daily lives now: the internet. Whether talking about stranger danger, privacy, or the fear that one might get doxed and attacked "irl," they engage our fear of the online world. They're also frequently about communication: Unfriended: Dark Web dives into the struggle of communicating emotionally online, Profile and Cam into the obfuscation of identity in online interactions, and Searching into how online relationships can seem more meaningful (and be more dangerous) than real life.Not every story is going to suit this format, obviously. Profile, for example, is an innovative adaptation and a perfect synergy of story and visual language, but you wouldn't make a fantasy movie in screenlife. Or would you?

To Screenfinity and Beyond

Bekmambetov is bullish on screenlife. In addition to the films he's produced thus far, he's got at least six more projects in development or production. A true believer, he's committed to screenlife as the visual language of the contemporary era, and he's bringing it to as many genres as possible. We'll be seeing a romantic comedy called Liked; a Romeo and Juliet adaptation told over Snapchat; a cyber-bullying drama; a fantasy movie; a superhero movie; and most tantalisingly, a film about Russian political trolls and election hackers.Even the medium itself is still developing. Obviously, the Screenlife Recorder software will continue to be improved upon. But delivery is being toyed with too. Screenlife movies are great in cinema, but can be effective in a different way on a laptop screen. Profile's home release will, alongside the edited version, include an interactive app in which you answer Skype calls, scroll through Facebook posts, and affect the way and order in which the story is told. The lines between screenlife films and video games like the terrific Her Story are blurry, and it's exciting.I'm not as frothy with enthusiasm for screenlife as Timur Bekmambetov. I don't think anyone can be. It's not a replacement for conventional filmmaking, and while it can probably tell stories in any genre, it can't tell every story. But Bekmambetov is right: screenlife is a perfect visual language for the here and now. Directed well, it's immersive and captivating to an extent few would have guessed. I certainly didn't expect one of these movies could wreck me emotionally like Searching did, but now even I am formulating ideas for screenlife films. In the internet age, an internet-specific filmmaking language is called for – and screenlife is as strong a contender as any. Bring on that fantasy epic, Timur.