A Horror Newbie Watches 'Night Of The Living Dead' For The First Time

(Welcome to The Final Girl, a regular feature from someone who has steered clear of horror and is ready to finally embrace the genre that goes bump in the night. Next on the list: George Romero's zombie classic Night of the Living Dead.)

This may come as a shock, but I kind of love zombie movies. I know this whole series is based on the fact that I wouldn't touch a horror movie with a 30-inch pole, but I would gladly double-tap on any zombie movie.

There's something about how zombie movies magnify emotions and present a warped reflection of the human condition — all beneath the pretense of blood and guts, of course — that draws me in. It's a simple B-movie premise, but zombies speak to larger ideas that I find utterly fascinating.

I can trace back my interest to its lame, nerdy beginnings. It began, as all passions do, with a college seminar. I had attended a seminar by one of my film studies professors, who introduced the theory that movie zombies were a manifestation of the deeper societal fears that plagued America at specific moments in time. It's by no means an original idea, but it blew my mind open. And it opened me up to the slow, reluctant acceptance of horror movies.

So it's time to go back to where it all began. It's time to finally explore George Romero's Night of the Living Dead.

(To preface this dive into my first time experiencing Night of the Living Dead, I have to admit that I'd already seen and fallen in love with George Romero's second Dead film, Dawn of the Dead. His treatise on the follies of capitalism shook me to my core, and cemented my deep, abiding respect for zombie movies. But I knew I had to go back to the beginning with Night.)

The Curse of the Modern Prometheus

We begin in a graveyard. It's an obvious (verging on on-the-nose) choice, but it almost feels refreshing in the larger context of the zombie genre. I've grown so used to zombie movies being cramped, claustrophobic affairs, that the opening scene in a wide, open field in the middle of rural America feels like Romero taking a page from another movie. And in a sense, he is. Horror is a genre that inevitably borrows from itself, either in homage or in metamorphosis of an idea. That's why this setting feels so classic, like it appeared straight out of a Gothic horror story. That's right, I'm bringing it back to one of the movies I covered for this series: Frankenstein.

James Whale's Frankenstein also opened in a graveyard, with the titular Doctor and his monstrous assistant Fritz robbing a grave for body parts to make his manmade creation. It's not surprising that Romero's zombies would be the next step in classic movie monsters after Frankenstein's monster. Like Frankenstein, the monster's appearance is heralded with a sudden, ominous thunderstorm. Like Frankenstein, the shambling caretaker who attacks Barbra (Judith O'Dea) and her brother Johnny (Russell Streiner) has long, gangly limbs that recalls the movements of Boris Karloff as Frankenstein's monster. But here, the monster is relatively unmarked, a normal human being for all intents and purposes, except for his heavy moments and dead-eyed expressions — intelligent enough to throw a rock through Barbra's car window, but still mindless in his chase. Later, the zombies even show a very Frankenstein-ian aversion to fire.

Mary Shelley called her creation "The Modern Prometheus," a reference to the Greek myth revolving around the Titan who is credited with molding man from clay. But after Prometheus' trickster ways — all in service of his precious creations — angered Zeus, fire was taken away from humanity. Prometheus is most famous, perhaps, for his tragic quest to take fire to the humans, gifting humanity with its source of light, warmth, life, and progress, but dooming himself to the eternal torture of being chained to a rock where his liver was gnawed out of him, only to be grown back the next day. Mary Shelley and other Romantic-era writers would interpret the myth of Prometheus as a cautionary tale about the dangers of overreaching progress — the aberration that is Frankenstein's monster being a chief example of this.

Like Frankenstein, Night of the Living Dead demonizes the advancement of science. The umbrella term "radiation" is blamed for the epidemic of the undead resurrected as limb-eating monsters, a clear reflection of the Cold War-era fear of nuclear war. Nuclear weapons are a power on par with God, Night of the Living Dead seems to say, and could only come back to bite us. Literally.

The Uncanny Valley of the Zombies

Let's get political.

I touched a little earlier on zombies as embodiments of our fears, but there's a political undercurrent here that most be explored. Because even mindless, shambling horror movie monsters are created in a political environment!

Night of the Living Dead has one obvious influence: the Cold War. Romero's film was released in 1968 during the height of Cold War-era tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. That much is clear in the "cause" of the zombie epidemic relayed during the vaguely scientific exposition toward the latter half of the film. But the zombies represent more than just the potential victims of nuclear holocaust. The zombies in Night of the Living Dead look barely different than the average human being — no grotesque, decaying flesh, no hanging entrails. There's an uncanny valley feeling to them: they resemble us so closely, yet they threaten to consume us. Like communism. Yes, you can laugh, it's a ridiculously blatant metaphor, but one that's in line with the era.

However, there's more to the metaphor than the Cold War. Night of the Living Dead arrived during a time of tumult in the U.S., when discontent with the Vietnam War was spilling over into Hollywood and the Civil Rights movement was reeling after Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination. Night of the Living Dead was one of the early cinematic responses to that sociopolitical chaos, with its popularization of the hordes of zombies leading the charge. As Vox writers Zachary Crockett and Javier Zarracina point out in their utterly fascinating article on the political roots of zombies:

Night of the Living Dead was also revolutionary in that it was the first prominent film to feature vast hordes of zombies (in the film, they are referred to as "ghouls"), as opposed to an isolated few — and to use those hordes as a symbol of an impending apocalypse.

For the first time, many Americans were being exposed to the wide-scale horrors of war. Graphic video footage of the Tet Offensive (1968) and piles of dead bodies were routinely broadcast. The "massification" of the zombie in Romero's film is a nod to this.

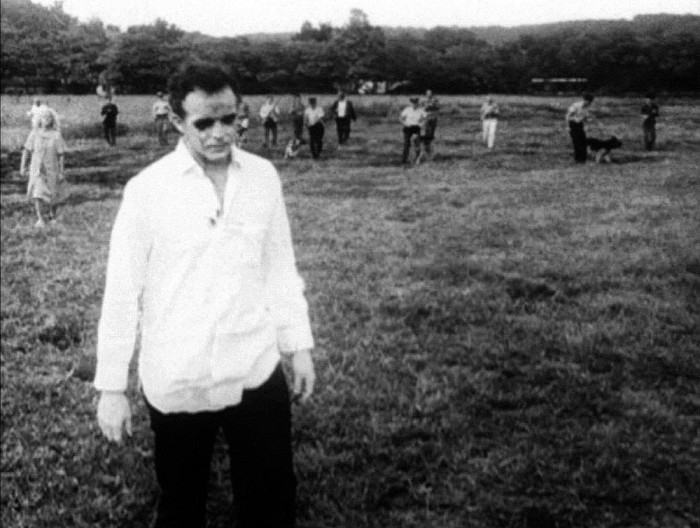

It's only as night falls that we see that horde of zombies, now finally decayed and grotesque — and sporting a fair bit of nudity, because hooray for exploitation B-movies! Interestingly, that stark image of the zombies against a wide expanse of field is echoed once again at the end of the film, when we see a helicopter shot of the armed men in a line patrolling for zombie targets. That parallel imagery is loaded with suggestion, especially when you consider how Night of the Living Dead ends.

Romero Started It

"Romero started it," Get Out director Jordan Peele tweeted following the news of the horror maestro's death. In his tweet was an image of Ben, the hero of Night of the Living Dead and the first major black protagonist in a horror film. He was a revolutionary character appearing on the tail end of a real-life revolution.

Night of the Living Dead came out four years after the passing of the Civil Rights Act, but merely five months after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. The country was teeming with race riots and racial tension, and yet here at the center of a defining horror movie, was a black man. Romero has famously said that he cast Duane Jones as Ben because he was simply the best person to audition, and any racial undertones were unintentional:

"Duane Jones was the best actor we met to play Ben. If there was a film with a black actor in it, it usually had a racial theme, like The Defiant Ones. Consciously I resisted writing new dialogue 'cause he happens to be black. We just shot the script. Perhaps Night of the Living Dead is the first film to have a black man playing the lead role regardless of, rather than because of, his race."

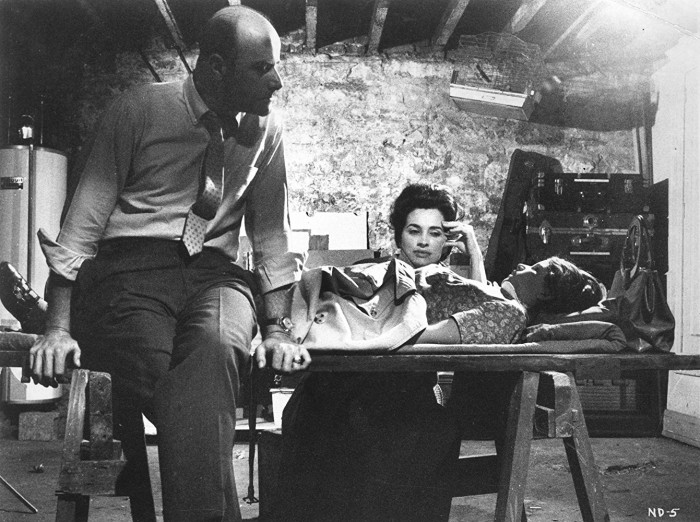

And yet, every one of Ben's actions and each scene with the alternately comatose and hysterical Barbra feels like pointed commentary. When Ben first enters, Barbra is frozen in fear, unsure if she's traded in one villain for yet another (coded) villain. There's an undercurrent of discomfort whenever Ben tries to shake Barbra out of her hysteria — even today, watching the scene of him unfastening her coat after he knocks her unconscious (with a punch!) is uncomfortably tense. The imagery of a black man accosting a white woman is stark even if it's unintentional, and Streiner, who also produced the film, admitted they were aware of this. "We knew that there would be probably a bit of controversy, just from the fact that an African-American man and a white woman are holed up in a farmhouse," Streiner said.

But intentional or not, Romero was a progressive director. The white male who "should" be the protagonist is killed almost instantly; meanwhile the black man who for decades has been coded as a threat, is the hero. And Ben is more than just a hero, he's a sensible everyman who is thwarted at every turn — first by the incontinent Barbra, then by the arrogant Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman), whose whiteness would usually have made him a de facto leader. But despite these physical and mental tussles, Ben comes out on top, more sympathetic and exemplary than ever.

That's what makes Ben's ultimate fate all the more horrifying. Having watched Dawn of the Dead, I fully expected a subversive ending like the one we saw at the end of that 1978 film — where the only survivors were a pregnant woman and a black man, a hopeful vision of society's future. Instead, the horrors are piled on top of each other in the last 20 minutes of Night of the Living Dead. The innocent daughter killing and eating her parents is traumatizing enough — though something I knew to expect from pop culture osmosis — and Barbra dying at the hands of her undead brother was almost predictable.

So I was shocked when Ben dies senselessly at the hands of the militia, his supposed rescuers gunning him down without a second thought. It would have been harrowing enough for the scene to simply cut to black, but it continues, with the credits rolling over the audio and news reel-like images of the men hauling Ben into a bonfire alongside countless other corpses. It is absolutely brutal.

I don't need to point out the obvious parallels to the countless number of black men who have been murdered by police officers or lynch mobs. It doesn't make the ending any less potent 50 years later, even after decades of zombie movies pushing us to an oversaturation point. It may have come at the very beginning of the zombie movie craze, but Night of the Living still has the most bite.

Final Thoughts

Although Night of the Living Dead is ostensibly a B-movie, it rarely feels like one. That's thanks in part to Romero's efficient, moody direction that heavily pays homage to Alfred Hitchcock (the rapid zoom effects paired with screeching music, the stark noir-ish lighting, the Hitchcockian blonde), and in part to Duane Johnson's stunningly naturalistic performance. He gives Ben an astonishing and modern countenance (save for perhaps his very measured enunciation), a sharp departure from the theatrical artifice of his co-stars.

It's probably what makes him so instantly sympathetic compared to his fellow archetypal survivors, whose introduction midway through the movie suddenly transforms the narrative into "Six Angry Men and Women." The wall-to-wall emotion threatens to make the film feel like a glorified play, until the tempers finally come to a boiling point between Ben and Harry, and the scene turns into a chaotic Lord of the Flies-style battle royale. Barbra's childish hysteria is frustrating to witness (it's one of the few elements of the film that hasn't aged well), as were the typical "beautiful people in a horror film acting dumb" storylines that we see, courtesy of Tom and Judy. Though were those so typical at the time?

Powerful, persuasive, and just a touch pulpy, Night of the Living Dead is yet another confirmation that the zombie genre is ideal for providing cultural commentary on a specific time and place. Night of the Living Dead strikes that perfect balance between glorious B-movie and unqualified masterpiece.