The Horror Was For Love: 'Bram Stoker's Dracula' And 'Crimson Peak' Are The Ideal Halloween Double Feature

If you're searching for the perfect Halloween double feature, you need not resort to repetitive slashers or gross-out gore-fests. You need only journey down a foggy, mossy path towards a towering structure in ruins, and find yourself embraced by the lush, ornate, blood-soaked worlds of Bram Stoker's Dracula and Crimson Peak. These two films are the fine wines of horror and gothic romance, paired perfectly with your gourmet Halloween meal. They live, and breathe, and die like so few other horror films.Primarily because these two films do not adhere strictly to the horror genre. Instead, they wade into the world of Gothic romance, where candles flicker as passions burn; where the old world clashes with the new; where dark secrets lurk in locked rooms. But you can break those locks, if you're adventurous enough; if you're brave enough. If you're willing to face the ghosts and undead that lurk in the shadows, and learn what truths they hold.These films dabble in death and terror, yes. But they also thrive on love. They have beating hearts which long to be listened to. They are somehow both horrific and delicate; like Venus Fly Traps that can ensnare and destroy if you get too close. As Halloween approaches, and you look for a break from sequels and jump-scares, why not draw closer to these two films and wrap yourself up in their chilly embrace?

This post contains major spoilers for both films.

The Blood is the Life

Bram Stoker's Dracula is not an outwardly romantic novel. In fact, it's a bit stuffy. There are lovers within its epistolary pages, but they're proper Victorian lovers, who are sure to keep most of their emotions in check. Dracula himself as a character is anything but romantic. Hollywood would eventually turn the count into a sexy figure, the ultimate bad boy with a cool cape to match, but in the pages of Stoker's novel, he's a foul, lecherous other, coming from far-off lands to invade pure and noble England. He calls women to him, but these events occur mostly off page, out of sight of the reader's eye. When intrepid heroes finally do confront him, he's a snarling, blood-lipped thing, unconcerned with seduction and more preoccupied with survival.When Hollywood got around to adapting Stoker's novel, the first thing they did was jettison most of Stoker's book. The German expressionist Nosferatu came closer to capturing Dracula (or more precisely, Count Orlok, as the film was forced to call him for legal reasons) as a creature of the night, with his rat-like fangs and beaked nose. But when Universal Pictures got the rights to Stoker's book, the story of Dracula was transformed into something else. The story began to grow more romantic; more somber. Dracula was no longer an ancient ghoul but a handsome fiend in evening wear who called pale white women to him with a deep glance.Every film iteration of Dracula henceforth would use the Universal film as its spring-board; almost every actor to play the Count would be riffing on Bela Lugosi's iconic performance. Lugosi's Hungarian accent would become the trademark Dracula voice. There would be occasionally deviations, but most rigidly adhered to this adaptation, Stoker's novel all but forgotten.That all changed in 1992 when Bram Stoker's Dracula bled fresh blood across cinemas everywhere. Screenwriter James V. Hart had gone back to Stoker's novel, resurrected moments other films had long neglected, and yet created something completely different. Hart's script had turned Dracula into something Stoker had never conceived: an anti-hero. Not the invading other, but a tragic figure worthy of some amount of pity, even as he caused death and destruction.Hart's script was good, but what truly brought Bram Stoker's Dracula to life was the lush, swooningly stylistic direction from Francis Ford Coppola. With a blitz of in-camera effects, the likes of which Hollywood seemingly would never employ again, Coppola turned Stoker's novel and Hart's script into a erotic dream; a blood-drenched fantasy, bursting with the type of life a vampire crawling from a fresh grave could only dream of.Bram Stoker's Dracula doesn't just change Dracula's characteristics, it gives him a backstory. Stoker was only marginally inspired by the notorious Vlad the Impaler when he wrote Dracula, but Coppola's film goes all-in on tying the myth and the real man together. Here, Dracula is a crusading knight for God, sent forth to rid 1462 Transylvania of heathen Turks. In these early scenes, Coppola has Dracula decked-out in blood-red armor, crafted by costume goddess Eiko Ishioka (the costumes, colorful, big, bold, and stitched and sewn with gorgeous detail, are practically characters themselves in the film). The armor looks like muscles from anatomy books brought to life, crossed with lupine features, giving the impression of a skinned humanoid wolf charging into battle.Dracula (Gary Oldman) is a fighter, but he's also a lover, devoted to his wife Elisabeta (Winona Ryder). When Elisabeta mistakenly hears that Dracula has died in battle, she kills herself, flinging herself from the tallest tower in Dracula's castle – a tower so high it hovers above the clouds themselves. Dracula pauses in his mass-slaughter when he learns of his wife's death, and storms home, incensed that this is how God would repay him. His renouncing of God is the direct cause of his vampirism. It doesn't really make much sense, but it doesn't have to. Coppola isn't interested in giving us answers; he's interested in building mood, and creating atmosphere. This is not a traditional narrative, it is a fever-dream; an erotic nightmare where all senses are heightened. In 1897, Dracula, now an undead creature of the night, a vampire who sups on blood, makes his way to London, where he finds his long-dead bride reincarnated as schoolmistress Mina (also played by Ryder). Drac also takes the time to seduce and feast on the blood of Mina's best friend, the wild and carefree Lucy (Sadie Frost). Dracula's treatment of Lucy is monstrous; he hypnotizes her and molests her as he takes the shape of a wolf. Yet when the chance presents itself to drink of Mina's blood, the vampire resists. His love, or at least what he perceives to be his love, for this woman is too strong. He thirsts for more than her blood; he thirsts for the idea of her – the idea that he can be with her, and that together they can be whole.Stoker's novel presents almost no relationship between Dracula and Mina till the last few chapters, when the Count mercilessly attacks her and makes her drink of his blood. Coppola's film turns this moment into a romantic moment. Once again, Dracula comes very close to drinking Mina's blood, but he stops himself. He doesn't want to damn her to his eternity. But Mina persists, demanding he baptize her into the vampire lifestyle. "Take me away from all this death," she begs.Turning Dracula into a tragic, romantic figure may defang the vampire, yet it works remarkably well in Coppola's film. It helps that the narrative never loses sight of what Dracula really is – a monster. He's a romantic monster, sure. But he's also one that takes lives with no regrets. "How can you pity such a creature?" Mina's husband Jonathan (Keanu Reeves) asks her at one point, and this seems to be the question Coppola's film is asking as well. Bram Stoker's Dracula does not excuse Dracula's actions, but it does strive for some sort of empathy.Yet empathy can only go so far. In the end, Dracula's true salvation comes in death, with Mina chopping off his head and breaking whatever hellish curse he inflicted on himself so many centuries ago. There can be no real comfort in this act, but their can be peace. Perhaps that's as good an end as any.

In 1897, Dracula, now an undead creature of the night, a vampire who sups on blood, makes his way to London, where he finds his long-dead bride reincarnated as schoolmistress Mina (also played by Ryder). Drac also takes the time to seduce and feast on the blood of Mina's best friend, the wild and carefree Lucy (Sadie Frost). Dracula's treatment of Lucy is monstrous; he hypnotizes her and molests her as he takes the shape of a wolf. Yet when the chance presents itself to drink of Mina's blood, the vampire resists. His love, or at least what he perceives to be his love, for this woman is too strong. He thirsts for more than her blood; he thirsts for the idea of her – the idea that he can be with her, and that together they can be whole.Stoker's novel presents almost no relationship between Dracula and Mina till the last few chapters, when the Count mercilessly attacks her and makes her drink of his blood. Coppola's film turns this moment into a romantic moment. Once again, Dracula comes very close to drinking Mina's blood, but he stops himself. He doesn't want to damn her to his eternity. But Mina persists, demanding he baptize her into the vampire lifestyle. "Take me away from all this death," she begs.Turning Dracula into a tragic, romantic figure may defang the vampire, yet it works remarkably well in Coppola's film. It helps that the narrative never loses sight of what Dracula really is – a monster. He's a romantic monster, sure. But he's also one that takes lives with no regrets. "How can you pity such a creature?" Mina's husband Jonathan (Keanu Reeves) asks her at one point, and this seems to be the question Coppola's film is asking as well. Bram Stoker's Dracula does not excuse Dracula's actions, but it does strive for some sort of empathy.Yet empathy can only go so far. In the end, Dracula's true salvation comes in death, with Mina chopping off his head and breaking whatever hellish curse he inflicted on himself so many centuries ago. There can be no real comfort in this act, but their can be peace. Perhaps that's as good an end as any.

A Monstrous Love

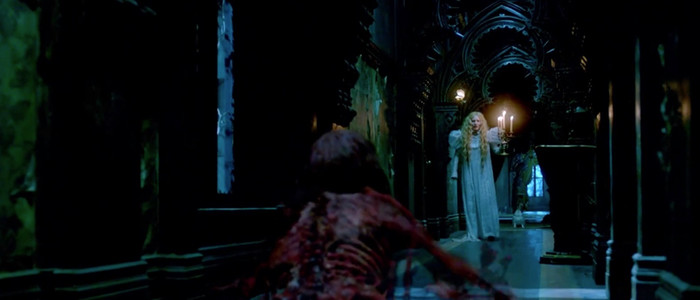

If Bram Stoker's Dracula has a cinematic kindred spirit, it's Guillermo del Toro's ornate Gothic romance Crimson Peak. Despite prominent horror movie elements, del Toro had a hard time selling the film to a casual movie-goer. Audiences expected something outwardly horrific, but what they were treated to was something more introspective, more lovely.Yet there is horror here. It is a horror born of trauma. Like Coppola's Dracula, del Toro's Crimson Peak is asking us to empathize with monsters. To find the fractured, injured humanity lurking beneath the cold, cruel exterior.The monsters at the heart of Crimson Peak may not be immortal vampires, but it would be easy to assume they are. Siblings Thomas and Lucille Sharpe (Tom Hiddleston and Jessica Chastain, respectively) are pale, moody, aristocratic creatures who dress in fine yet outdated clothes, and come stalking to a foreign land looking for prey.The Sharpes come to America from England, where they present themselves as wealthy landowners seeking investments. But the truth is their money has run dry, and all they really own is their sprawling, rotting mansion, Allerdale Hall. Thomas proceeds to woo would-be novelist Edith (Mia Wasikowska), and after the brutal murder of Edith's father, she marries Thomas and travels back to Allerdale Hall with him and Lucille.Thomas and Lucille plan to slowly poison Edith to death and inherit their fortune, as they've done to several other women in the past – women who now haunt the gothic halls of Allerdale. Just as the costumes of Bram Stoker's Dracula are like characters themselves, so too are the sets used for Allerdale Hall in Crimson Peak. The dark, elaborate rooms and halls that make up the mansion are lined with spikes like fangs, and cluttered with torture chamber-like furniture. The red, muddy soil the building sits on seeps up through the floors like blood. Yet there's beauty in the mansion as well, particularly in the main entrance way, where a hole in the roof lets in the elements, be it falling leaves or falling snow.Thomas and Lucille have ill intentions for Edith, yet like Dracula, Thomas finds himself attracted to his potential prey. Despite their marriage, the couple never grows very physically intimate. Yet when the two travel away from Allerdale Hall and get snowed-in elsewhere, a passionate night of lovemaking changes things. At least, Thomas would like it to. Like Dracula, Thomas is thirsting for Edith, as well as the idea of her – the idea that she can provide him with some sort of freedom. Yet Edith is more than just some ideal. She's not just another ornate object to place within the confines of Allerdale, but a living, breathing, vibrant young woman who thought what she had found with Thomas was true love. And it is, of course, only a matter of time before Edith learns of the danger she's in.If Dracula had his vampirism pulling him towards darkness, Thomas has Lucille. Lucille has been sheltering, protecting and manipulating Thomas all his life, from when they were very young and living under the thumb of their abusive mother. The backstory of these tragic yet murderous siblings lends that air of empathy – abused and tormented as children, we can understand why the Sharpes turned out so monstrous.Thomas and Lucille are close – very close. Their entire plot falls apart once Edith discovers the siblings in an incestuous embrace. "The things we do for love like this are ugly, mad, full of sweat and regret," Lucille says. "This love burns you and maims you and twists you inside out. It is a monstrous love and it makes monsters of us all."It would be hard to see the murder and pain that accompanies the characters of Crimson Peak as representing love and romance, yet to these damaged souls, that's exactly what it is. It is a warped, deranged love, but it's all they have. In the end, just as with Dracula, there can be comfort here, only peace. Peace in the form of death, as Thomas and Lucille meet violent ends. Thomas perhaps finds freedom in his demise, drifting away into the mist. Lucille, however, isn't so lucky, stuck haunting the rooms of the sinking, dying Allerdale Hall.

Yet Edith is more than just some ideal. She's not just another ornate object to place within the confines of Allerdale, but a living, breathing, vibrant young woman who thought what she had found with Thomas was true love. And it is, of course, only a matter of time before Edith learns of the danger she's in.If Dracula had his vampirism pulling him towards darkness, Thomas has Lucille. Lucille has been sheltering, protecting and manipulating Thomas all his life, from when they were very young and living under the thumb of their abusive mother. The backstory of these tragic yet murderous siblings lends that air of empathy – abused and tormented as children, we can understand why the Sharpes turned out so monstrous.Thomas and Lucille are close – very close. Their entire plot falls apart once Edith discovers the siblings in an incestuous embrace. "The things we do for love like this are ugly, mad, full of sweat and regret," Lucille says. "This love burns you and maims you and twists you inside out. It is a monstrous love and it makes monsters of us all."It would be hard to see the murder and pain that accompanies the characters of Crimson Peak as representing love and romance, yet to these damaged souls, that's exactly what it is. It is a warped, deranged love, but it's all they have. In the end, just as with Dracula, there can be comfort here, only peace. Peace in the form of death, as Thomas and Lucille meet violent ends. Thomas perhaps finds freedom in his demise, drifting away into the mist. Lucille, however, isn't so lucky, stuck haunting the rooms of the sinking, dying Allerdale Hall.

A Halloween Double Feature

Nothing beats watching good horror films on Halloween. The one-two-punch of Bram Stoker's Dracula and Crimson Peak could be exactly what you're looking for this year. There's always room for slashers, zombies and all other manner of traditional horror films, yet there's something incredibly special about taking in these two gothic delights back to back.You begin to notice themes and similarities, not because Crimson Peak is borrowing from Dracula, but rather because both films are working within the same established rules of Gothic romance. Both films feature strong turn of the century heroines coming to terms with monstrous men in their lives. And both women have well-intentioned normal men who pine for them, yet clearly aren't meant to be the one – Mina in Dracula has her loving yet boring husband Jonathan Harker, and Edith in Crimson Peak has the loving yet boring Dr. Alan McMichael.There's an incredible relief in the fact that neither Dracula or Crimson ends with their respective heroines deciding the boring, normal man is the one for her after all, They've vanquished their monster lovers, but that doesn't meant they have to flee into the arms of someone dull and passionless.With a mix of lush production design, blood-drenched horrors, and even sexiness, Bram Stoker's Dracula and Crimson Peak blend together like one sweet, strange, scary dream leading into another. You can be haunted by these films, yet also stimulated. There's more to horror than just a quick, good scare. There's romance, too.So if it's more than simple scares you seek as Halloween arrives this week, take refuge in the haunted corridors and bloody passages of Bram Stoker's Dracula and Crimson Peak. It'll be a Halloween to remember, full of creeping horror, swooning passion and, yes, even a few jump scares.