A Horror Newbie Watches 'Halloween' For The First Time

(Welcome to The Final Girl, a regular feature from someone who has steered clear of horror and is ready to finally embrace the genre that goes bump in the night. Next on the list: John Carpenter's 1978 seminal slasher film, Halloween.)

Ah, Halloween, my old nemesis. We meet again.

If you remember from my first column, the 2007 remake of Halloween is the bane of my relationship with horror movies — a source of teenhood trauma that forever put me off slasher films...and horror remakes directed by Rob Zombie. The remake that I saw was gratuitous schlock that even I — as a horror hater who was only vaguely aware of the ubiquity of the Michael Myers Halloween mask — couldn't fathom living up to the far-reaching legacy of John Carpenter's 1978 original.

The original Halloween spawned several sequels, one of the most iconic horror villains, and the trope upon which my column name is based. And another movie is on the way, with Jamie Lee Curtis set to reprise her role in a sequel that ignores about half of the films in the franchise. So in honor of all final girls out there, I had to pay my dues to the OG Final Girl, Laurie Strode, and watch the original Halloween.

Sex and the Slasher

When I first started writing for /Film, nearly everyone I told asked me, "So...you're writing about horror movies?" I would always adamantly deny it, but here we are — several months later and I'm writing about slashers.

But, despite being the movie that birthed the slasher genre as we know it, Halloween is surprisingly bloodless. My impression of slashers was always somewhat conflated with "torture porn": gratuitous, grisly, and brutal. The 2007 Halloween remake was certainly that, and it had to have come from somewhere. But there are only maybe three scenes in the 1978 Halloween that could be described as particularly gruesome — the first of which happens in the first 10 minutes of the movie. It's perhaps this scene, of a six-year-old Michael Myers stabbing his nude sister to death, that would go on to influence future slashers' fixation on sex and violence. (It's an easy formula: phallic knife + naked female body, and you've got all the subliminal messages that you need.)

But the unsettling thing about this first death scene isn't the shock of violence or even the nudity. It's the voyeurism. The entire opening sequence takes place from the unsteady POV of young Michael Myers, who later dons a clown mask with slitted eye holes when he does the deed — resulting in a murder in which you see only glimpses of the sister and her body. I can see how Carpenter drew heavily from Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho and its own fixation with voyeurism — not to mention the parallels between Donald Pleasence's Dr. Sam Loomis and Detective Milton Arbogast.

But "while Psycho opens with the camera slowly tracking in through a window to intrude on two lovers in a seedy hotel room, Halloween takes it a step further," film historian J.P. Telotte points out. "As a result of this shift in perspective from a disembodied, narrative camera to an actual character's eye ... we are forced into a deeper sense of participation in the ensuing action." It's a perspective that continues to be sprinkled throughout Halloween, accompanied by the intimate sound of Michael Myers' heavy breathing. But as deep as Carpenter places us in Michael Myers' POV, remarkably, there is never any danger of empathizing with him. We may see through his eyes, but he manages to remain the biggest mystery of the movie.

It Was the Boogeyman

"It was the boogeyman." "As a matter of fact, it was."

The two classic horror films I've seen so far for this column seem intent on building their own pop culture mythology. Frankenstein drew on classic Greek myths and German cinematic influences to create a firm foundation for the monster movie, while Halloween merges the language of film with fairy tales. Throughout the night in which Halloween takes place, Laurie and her friends watch classic black-and-white monster movies, their gaze barely averting from the televisions. It doubles down on the movie's themes of voyeurism, but it also introduces a pop culture-ingrained mythology for Michael Myers. He is not a human, but one of the monsters from the movies — a veritable boogeyman.

Dr. Sam Loomis insists on speaking about Michael Myers in only histrionic language, calling him "the evil" or the devil incarnate, producing an even denser air of mystery around this villain. "I met him 15 years ago, I was told there was nothing left," Loomis monologues at one point. "No reason, no conscience, no understanding, and even the most rudimentary sense of good or evil, life or death, right or wrong. I met this 6 year old child with this blank pale emotionless face and the blackest eyes...the devil's eyes."

Michael Myers' superhuman strength and seemingly endless close calls with death only serve emphasize this "boogeyman" mythology. It's the franchising of a villain. Soon Michael Myers would be followed by other iconic human monsters who would terrorize unwitting teens: Freddy Krueger, Jason, Jigsaw. But Michael Myers feels like the first human villain to receive the same horrified awestruck treatment as a classic movie monster and this is why the mythology-building is so effective.

There’s Something About Laurie

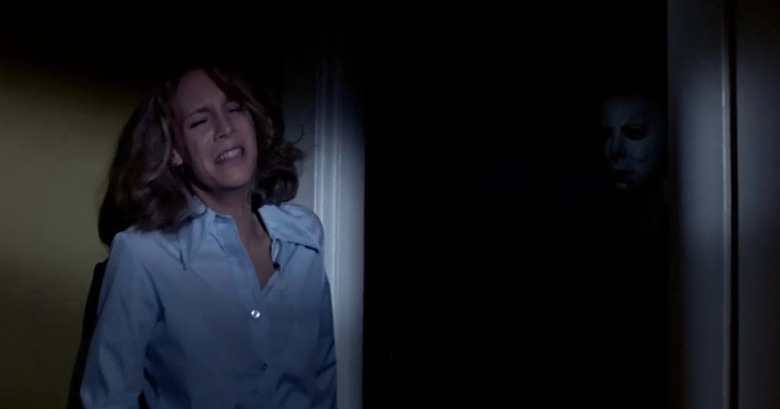

Laurie Strode with her cardigans, long skirts, white tights, Farrah hair, and deep voice cuts an interesting figure. She just doesn't look or act like a traditional "scream queen." Yes, I know that Curtis would end up be crowned the queen of the screams after her performance in Halloween, and yes I know that scream queens aren't necessarily limited to delicate, flailing blondes. But there's something austere about Curtis' performance as Laurie Strode, which only becomes more clear as she sheds her dowdy sweaters for her signature blue button-up and high-waisted jeans.

Her clothes sign her fate just as much as Curtis' subdued, perceptive performance. Covered head-to-toe for the entirety of the film, Laurie is the only one of her group to be coded as "the good girl" — and her cardigans and long skirts can say that even more loudly than she can. But long skirts aren't enough to deem her "worthy" of survival and final girl status, it's her masculine outfit of the collared shirt and jeans — flattering of her figure but still projecting a certain machismo. That's the formula to the final girl, it seems: a balanced dichotomy of feminine and masculine, plus the requisite chastity.

It's so fascinating to see the final girl at her genesis. She's like a confluence of both archaic and progressive '70s second-wave feminism ideas about the idealistic woman: she's smart, she's subtly sexy, she's chaste, she's got agency, but she can still cry. She feels like an early prototype for the "badass female character" role that I hate so much. As a type, the final girl feels backwards — a patriarchal attempt to squeeze women into Madonna-Whore complexes. But as Laurie Strode — lone, complex, and the first of her kind, it feels a little revolutionary.

So Much for Peripheral Vision

My least favorite thing about horror movies is how they immediately cut their characters' IQs in half. Except for Laurie — and perhaps Dr. Sam Loomis, who really acts like the resident loon of the movie — everyone is an idiot who has terrible peripheral vision.

The good thing about the characters' sudden onset of idiocy: it makes for good filmmaking. While the characters become increasingly unsuspecting, the audience becomes even more hyper aware of each tiny detail in the film. The build-up of suspense is masterful and Carpenter makes sure to build a sense of paranoia with each steady wide shot that lingers too long and each ominous shot of Michael Myers standing in the background. The loss of peripheral vision makes for some of the most terrifying and beautifully composed shots in the movie: Michael Myers rising up from "the dead" in the background as Laurie sobs in the foreground, the suspense of Annie on the phone as Michael Myers approaches her in a cheesy sheet. And the jump scares, oh man, I yelped every time. Without the characters constantly looking out the corner of their eye, it forces the audience to, and it makes them an active participant in the horrors affecting these people.

Still, there's only so many moments I can take of Laurie seeing Michael Myers in broad daylight while everyone else misses him because they were rummaging through their bags. Or Annie and her boyfriend doing the deed when a shadow walks by them from two feet away. And for once, just turn on the light!

Final (Girl) Thoughts

Halloween surprised me. It was less about violence than it was about voyeurism, and the violence that it did have was relatively bloodless and not even as erotic as I assumed (though you could argue that being choked to death has its own intimate implications). As someone who adored Hitchcock's Psycho, I was pleased with the constant homages and nods to it — especially in its emphasis of suspense punctuated by random bursts of violence.

Laurie Strode too, surprised me. I'm not sure what I expected of the original final girl, but she impressed me, even 30 years later. Before she was a trope, she was a complex, flawed character who — considered outside of the context of her genre and the copycats she spawned — was quite revolutionary.

I'm still not completely sold on the slasher, however. The mythology-building of Michael Myers as some sort of urban legend boogeyman is effective, but didn't compel me. I don't mind villains that are pure forces of chaos, but Michael Myers was just not...enough for me. Maybe it's the legacy that Halloween left, or how much that damn Michael Myers mask has spread through the costume shop markets. Michael Myers is the least interesting part of the movie. But give me a Laurie Strode franchise any day.