Keep Watching: How 'Creep' And 'Creep 2' Revitalize Found Footage Horror

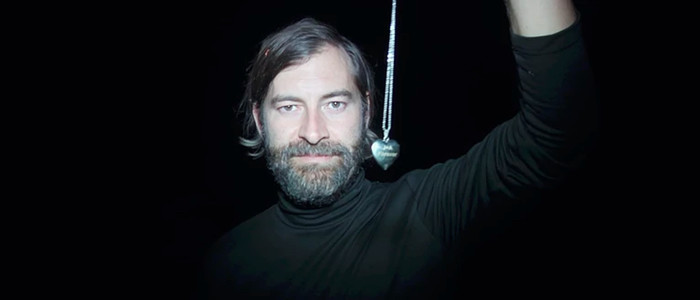

The found footage horror film is, for the most part, dead. The cause of death was overexposure – after producers realized how quick and easy (and cheap!) it would be to create such films, the multiplexes became choked with them. You couldn't swing a dead cat without hitting a found footage/faux documentary chiller (note: please don't swing cats, alive or dead; it's mean).Yet every now and then, someone will resurrect the idea, for better or worse. Usually worse. Then there's the Creep series. With Creep and Creep 2 (with the potential for a Creep 3), Patrick Brice and Mark Duplass have found clever new ways to reinvigorate the found footage subgenre. Better than that, they've found ways to actually make such a medium seem practical in terms of the story.Spoilers follow.

Found Footage: A Crash Course!

Oh heck, do I need to go over what "found footage" horror is, just so we're all clear? I suppose I should. I'll make it brief. The found footage horror subgenre consists of films that are shot in a faux documentary style, as if the characters in the films themselves are recording everything. More of than not, this footage is presented to the audience as having been recovered following a terrible incident. There are exceptions to this, of course. Sometimes we're supposedly seeing a real documentary that's been finished, capturing a terrifying scenario.The first truly noteworthy found footage horror film is 1982's Cannibal Holocaust, which is purported to be footage shot by a missing documentary film crew who vanished in the Amazon. I'm not going to talk much about this movie, because it contains actual scenes of animal cruelty, and to that I say "Fuck right off." But the film caused a stir when it was released, with some audiences believing a lot of the human deaths depicted on screen were real, and that director Ruggero Deodato had actually made a snuff film.With Cannibal Holocaust, the seeds for the found footage horror subgenre were firmly planted. Practically anyone could take this set-up and run with it, but surprisingly few did. Few of note, at least, save for the 1993 French film Man Bites Dog. Not exactly a straight-up horror film, Man Bites Dog was a satirical yet often brutal experience that presented itself as a documentary about a serial killer, with the serial killer himself serving as our guide. Things don't end very well for the killer or the film crew following him around.The true turning point for found footage came with 1999's The Blair Witch Project. Presented as assembled footage recovered from three missing film students, The Blair Witch Project remains the absolute best example of how to use the subgenre. The title card at the beginning sets everything up in a few sentences – three students went into the woods. "A year later their footage was found," is the last sentence on the screen, indicating that while the footage may have been found, the students clearly weren't. Here, the reasoning for the found footage framing device makes perfect sense – these were film students making a documentary, something terrible happened to them, their footage was found, someone pieced it together into a coherent narrative. We have all the tools we need to fully accept this scenario, and the film, with hyper-realistic performances and supernatural elements that always occur off screen, seems real enough to convince us this might be the real deal. As indeed it did, with certain viewers still convinced years after the film's release that it was a true story.The box office success of Blair Witch was a catalyst for horror filmmakers. Suddenly, anyone with a camcorder could make their own horror movie. More and more found footage fright flicks found their way to the big screen, but most of them lacked the mood and commitment to set-up of Blair Witch. There were exceptions to the rule. The first Paranormal Activity film, about a couple in California filming the ghostly encounters inside their house, was highly effective. Cloverfield employed found footage tricks to a Godzilla-style scenario. REC had a TV journalist's puff piece suddenly turn into a zombie outbreak. Unfriended was made to look like a series of Skype and video chats were assembled together into a tale of ghostly revenge.These films work, but they also always contained a lingering question: does this story need to be told via found footage? It made sense for The Blair Witch Project – indeed, without the found footage element, that film would not be nearly as effective as it is. But would Cloverfield have worked had it not employed the same trick? Probably. Would the glut of Paranormal Activity sequels be the same sorts of films told in a more straightforward manner? Most likely. Then you have uninspired drivel like The Last Exorcism, where it becomes clear that there's absolutely no way most of the stuff we're seeing would appear as it does in a real documentary. It's too staged; too forced.And that's the secret. That's what Blair Witch understood most of all, most likely because at the time it was so fresh and new and the "rules" of found footage hadn't been fully established yet. Blair goes to great lengths to make everything seem logical, and real, even as the paranormal sets in. There's always another possible explanation for what we're seeing – maybe it's not a witch, but someone pulling a terrible prank. If a filmmaker is unwilling to fully commit to the found footage concept, why even bother using it?

Creep

Have you ever found yourself in a situation where you force yourself to tolerate another person's weird, uncomfortable behavior just to avoid seeming rude? Where someone keeps acting completely off-kilter, but you don't want to draw attention to it, because that would break the social contract? That's what Patrick Brice's funny, unnerving Creep is like, stretched to a feature-length film.The brain-child of Brice and Mark Duplass, Creep takes an awkward situation and makes it even more awkward, to the point where the tone shifts from comedy to horror in a subtle yet jarring manner. As a society, many of us have adapted (or perhaps the correct word would be "devolved") to being openly cruel and confrontational when we're in the comfort of our own homes and hidden behind a computer screen, but it's a different story entirely in person. Most people want to avoid confrontation. Creep asks, "What if someone who was truly disturbed exploited that to deadly effect?""Patrick had made this documentary short called Maurice about the owner of one of the last pornography theaters in Paris," Duplass said, "and I noticed the way he was and what he got from this guy. So there was a trust, and it's the nature of how Patrick is. He just loves people and he doesn't judge them...And I saw that element and I was like, what if we take that element in you and created a more extreme character, someone who is just desperate for love and will really stick around and trust people too much?"In Creep, Brice plays Aaron, a videographer looking to make a quick buck. He answers a vague Craigslist ad and travels to a scenic yet very remote mountain cabin where he meets his client, the mysterious Josef (Duplass). Josef explains that he's dying of cancer, and he wants Patrick to record a day in his life for his unborn son. Josef admits he got this idea from the Michael Keaton movie My Life, and while Aaron has no qualms with the job at first, Josef's increasingly strange behavior starts to give him pause. The very first thing Josef asks Aaron to do is to film him taking a bath as he pantomimes giving his unborn baby a "tubby time." Soon after, Josef introduces Aaron to the mask for a character he claims his father made up – a disturbing wolf named "Peachfuzz." It only gets weirder from there.When Creep came out in 2014, found footage as a whole had become boring and unnecessary, especially in regards to horror. There was a pointlessness to it – why, we'd ask ourselves again and again, is this even being presented in this style? Yet Creep found clever new ways to make it all work. In one sequence, the camera is left running on a table, filming a wide shot of Aaron frantically searching for his missing keys that is very effective. Later, there are several clever transitions, as the camera is spun away from the action to reveal that it's actually been filming another screen showing footage the entire time – found footage within found footage. Little tricks like this add a neat aesthetic to Creep.For most of it's run time, the audience isn't entirely sure where Creep is going. Duplass, as the unnerving Josef, uses his mumblecore roots to full effect; he has a remarkable ability to talk-out what he's thinking and make it somehow sound both realistic and also subtly false. When Josef's behavior escalates to levels that even the polite Aaron can't ignore, we can almost believe Josef's explanations because Duplass sells them so well. Rather than just a one-note weirdo, Duplass creates a layered character with Josef. Every time Josef does something weird, he's quick to offer a seemingly genuine apology. It makes the character somehow endearing despite all his lunacy. All of this serves to make Creep's ending, where Josef murders Aaron, all the more shocking. This sequence too makes remarkable use of the found footage angle, with Josef setting a camera up at a great distance, presenting us with a wide shot that lingers as Josef, wearing his Peachfuzz mask, creeps up on Aaron and axes him to death.The viewer can't help but come away with a sense of shock. What seemed like an incredibly awkward comedy has just become something more terrifying, and the found footage aesthetic has lulled us into a sense of security in a way. Since this has been Aaron's movie the whole time, we assume that he gets out of this okay. Yet the final moment of the film reveals that this isn't Aaron's movie. It's Josef's. We've been duped, and rather than inspiring anger, this twist is remarkably effective.

Creep 2

Creep 2 takes everything Creep did, and amps it up. It also improves on the formula. There's a freeing aspect to this film, mostly because we're in on the twist from the jump. While the first Creep kept audiences guessing just what was up with Duplass' character, we know his true nature from the very start.Creep 2 doesn't play around. The very first scene focuses on a befuddled man (Karan Soni) receiving a video in the mail. Through dialogue, we learn that this is just one of several videos he's received, all of them pointing to a stalker. His friend comes over, and the friend turns out to be Duplass' Josef, now going by "Aaron" – the name of his last victim. Duplass quickly reveals that he's been stalking Soni's character this entire time, before swiftly, and violently, murdering him. This all happens in the first few minutes of the film, shot through a hidden camera placed inside the Peachfuzz mask.Josef (from hereon referred to as Aaron) isn't just a serial killer. He's a filmmaker. This solidifies what the ending of Creep set-up: a killer who has spent his murderous career filming his crimes. It enables Creep 2 to continue with the found footage angle, and use it to great effect. Although we can't help wondering just where this footage is coming from. Is it truly being "found", or is it being sent to us by Aaron? The way he sent footage to his victim at the start of this film? Are we his next victims?The framing device for Creep 2 involves yet another filmmaker who gets sucked into the killer's game. This is Sara (Desiree Akhavan), the maker of a failed YouTube series, Encounters. In her videos, Sara answers want-ads from desperate men; men who are looking for some sort of connection that borders on a fetish. Men who want to be held, and mothered. Men who are lonely, and desperate, and just a little bit sad.Sara's videos aren't exploiting or mocking these men, but they're also not exactly setting the internet on fire. So even when she answers a vague ad placed by Aaron, she thinks she might be close to ending her series. That all changes when she meets Duplass' character, who doesn't beat around the bush here like he did in the first film. Right from the jump, the killer reveals his true nature. He tells Sara he's a serial killer, and he wants Sara to film him.This set-up allows Creep 2 to flip the formula established by the first film. Even though we know right away that the main character is a psycho killer, Sara continues to have her doubts. She thinks Aaron is just a lonely loon, and she also thinks filming him can make for a great episode of Encounters. The tension is ratcheted up, as we wait, on edge, wondering when it will dawn on Sara what kind of danger she's in.By the film's end, Brice and Duplass reveal they have pulled a fast one on us yet again. We should've seen this coming, but perhaps we were too caught up in the narrative. Once again, we learn that this film belongs to Aaron, or Josef, or whatever his true name is. He's the filmmaker, and this is his movie we've been watching, not Sara's. Again, it's found footage of found footage. A ouroboros; the snake eating its own tail in an eternal cycle that we can't break out of.

Keep Watching

What makes Creep 2 so creepy is the way it continues to find clever new ways to put the faux documentary angle to good use. In 2017, we as a society are even more obsessed with filming and recording ourselves than when the first film hit in 2014. We've become a society that lives through screens, always desperately trying to capture a moment with our own personal recording devices we have tucked away in our pockets. If we don't Instagram, or SnapChat, or even just take a photo of a moment, can we even truly say it happened?We've been conditioned to act like this. To in a sense put on a show for our peers, desperately hoping someone, somewhere, finds a connection. This logic is hardwired into the Creep series, where the filmmakers should use common sense, turn the camera off, and get the hell out of there. But they don't. Because they want that connection. They want to record it all, and hope that the recording will somehow serve as a landmark. A sign that for a moment in time, they existed.As the situation in Creep 2 becomes more and more dangerous, Sara grows more and more apprehensive. But she keeps filming. She has to. She needs that connection. She needs her work to mean something, and the only way it could mean anything is if someone notices. At the start of the film, after Aaron tells her he's a serial killer, she confesses to her camera that she usually doesn't do things like this, but maybe that's the reason why no one is watching Encounters. She needs to take a risk, hoping it leads to a reward.Perhaps that's the true brilliance of the Creep series. We as a society are forever doomed to be stuck searching for connection through documentation. Photos of the meals we eat plastered across Instagram. A sea of a million rectangular lights going up at concerts as the crowd forgets to watch the show and instead attempts to contain it. The Creep series, like the best found footage films, understands that as a society, we not only have to keep filming, we also have to keep watching. We're a society of voyeurs looking for a fix. Like Jimmy Stewart in Rear Window, we're forever stuck gazing out at our neighbors, and in turn wondering if they're gazing back at us. The Creep series understands that if you've ever had the funny feeling that you're being watched, it's probably because you are. How terrifying is that?