The Unpopular Opinion: 'Death Sentence' Is The Only 'Death Wish' Remake We Need

(Welcome to The Unpopular Opinion, a series where a writer goes to the defense of a much-maligned film or sets their sights on a movie seemingly beloved by all. In this edition: not only is James Wan's Death Sentence a good movie, but it's also the only Death Wish remake we need.)

There's a new Death Wish movie hitting screens this week, and while I'll walk into it the same way I approach every film – hoping for greatness – it's difficult to actually be all that optimistic. Not only has this remake been made redundant by four decades' worth of movies about white men getting revenge with guns, but its journey towards production has seen a handful of interesting choices sidelined in favor of bland mediocrity. Instead of the once-rumored Benicio Del Toro for the lead, we now have Bruce Willis' disinterested corpse. Instead of the Israeli filmmakers behind Big Bad Wolves announced for the director's chair in early 2016, we now get the not-so subtle talents of Eli Roth. Instead of a fresh and interesting revenge tale, we're getting what appears to be another empty and generic action film. (Seriously, watch the trailer.) It's all made even more unfortunate by the realization that the only Death Wish remake we needed already came and went with nothing but empty theater seats and a 20% score on Rotten Tomatoes left behind.

Literary Beginnings

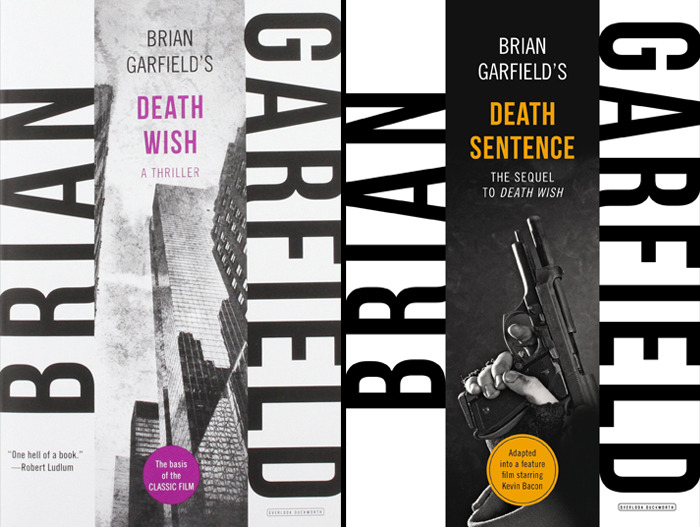

Like 1974's Death Wish, 2007's Death Sentence is also based on a novel by Brian Garfield. It was published three years after its far more famous sibling, and while it's a direct sequel that follows Paul Benjamin's (Paul Kersey in the films) further adventures, it differs somewhat in its approach towards the idea of vigilantism. The novel sees Benjamin trying to settle back into a regular life only to be disturbed by both new criminals and copycat vigilantes who are far less concerned about the possibility of causing collateral damage or taking innocent lives. There's a commentary of sorts on the dangers of taking the law into your own hands, and it's no surprise that Hollywood went in a more sensationalist direction with its own sequel and eventual franchise.

Garfield says he wrote the novel as "a sort of penance" for Death Wish and its clear celebration of vigilantism. He wasn't denouncing the earlier novel, but he wanted to offer a rebuttal to the idea he himself propagated regarding revenge and vigilante justice being a suitable answer to violence. That downer intrusion of reality isn't exactly a recipe for audience fun, though, so just as Robert Bloch's Psycho II novel was optioned and ignored in favor of more Norman Bates shenanigans, Garfield saw his creation's onscreen future equally confined.

Death Sentence was adapted for the screen by Ian Mackenzie Jeffers, a writer whose only other screen credit is as co-writer of Joe Carnahan's excellent The Grey. (Perhaps not so coincidentally, Carnahan was originally set to write and direct the new Death Wish before leaving the project behind. His script remains.) Jeffers' script abandons the connection to Death Wish along with its infamous character, but he keeps its questions and themes. Instead of Paul continuing his fight against crime, we're introduced to a new lead character along with his wife and two sons. Violence takes one of their lives, putting protagonist Nick Hume on a course for vengeance, but unlike the characters played by a stone-faced Bronson or somewhat sleepy Willis, our "hero" hasn't got the first clue when it comes to murder or mayhem.

Happily, director James Wan does.

The Relevance of Death Wish

First, though, what makes 1974's Death Wish such a precious bird anyway? Any film can be remade, and just as an adaptation can't ruin the book on a shelf, a remake can't hurt the original. But some films can make the thought of a remake seem unwise due either to the original's quality or place in time. No one would ever be foolish enough to remake John Carpenter's The Fog or John Carpenter's Halloween, for example, as neither film can be improved. Unlike those two movies, Death Wish is no piece of genre perfection – there are acting issues throughout, dialogue is often ill-fitting, and the tone is only sporadically as grim as it probably should be – but it's a film that very much speaks to and belongs in its exact time.

After decades of flat-lining, the violent crime rate in New York City began a meteoric rise in the 1960s and 1970s. The city's citizens grew increasingly frightened and terrified of a new breed of criminal fueled by gang activity, drug use, and questionable fashion choices, and into that powder keg was tossed an avenger named Paul Kersey. He did what the average Joe couldn't and turned the tables on thugs, rapists, and wannabe killers alike, and in the process he became the mustachioed slice of catharsis the population desperately needed.

Charles Bronson's presence in the role was a major factor, too. He was already well-known as a tough guy onscreen, but prior to his two films immediately preceding Death Wish – Chino and the terrific Mr. Majestyk – his characters were typically hardened and capable well before their respective films began. Kersey, though, is an average guy with a regular job and a general distaste for guns who's pushed too far and too fast by tragedy. The film left audiences empathizing with Kersey's rage and cheering him on as he mowed down muggers with impunity. People needed to see that someone could stand up to the encroaching spread of crime, and Death Wish gave them that image.

The Redundancy of Death Wish

Of course, it also gave them four sequels (the last two of which are subtitled The Crackdown and The Face of Death) over twenty years and the creation of a sub-genre that's still going strong today. Kersey stops growing as a character and instead becomes a lightning rod for violent criminals as everyone in his life falls victim to rape, assault, and/or murder, leaving him to clean up the mess. He does so typically by making even bigger messes – he uses a rocket launcher on a deserving scumbag in the third film – as the films devolved into pure action silliness.

He wasn't alone, either: films about vigilantes and people taking the law into their own hands became a popular story line for the B-movie crowd. The Exterminator, Defiance, Rolling Thunder, Vigilante...they're undeniably entertaining movies, but while other sub-genre outliers found a home in blaxploitation or with gun-toting women in the lead, most of these examples were content putting white men up against usually non-white but visibly villainous thugs who they inevitably beat to the sound of a rousing score and the faint echo of off-screen applause. It became formulaic even before Death Wish's end credits stopped rolling, leading to the likes of Fighting Back, The Boondock Saints, The Punisher, and more.

A remake today feels wholly extraneous in a world where hundreds of similar films already exist and in a country where the crime rate is in a relative decline. There's just no call for it in a popular culture already overflowing with violent action movies about bad guys catching heat from the wrong end of a gun. Don't get me wrong, I love these kinds of films and the simple pleasures they deliver, but a Death Wish remake with Bruce "Zzzz" Willis in the lead will have the same impact as a film titled Acts of Violence, First Kill, Marauders, Precious Cargo, Extraction, Vice, The Prince, or any number of other very real movies starring Willis over the past four years.

James Wan's Death Sentence Is the Only Death Wish Remake We Need

As mentioned above, Wan's film does not match Garfield's novel in plot specifics, but it retains the most integral elements responsible for elevating it above the bloody fray. Nick (Kevin Bacon) is still an average white guy who loses something very precious through an act of malicious cruelty and violence. Lacking faith in the court system and visibly distraught by his son's murder, Nick tracks down one of the young men responsible (Matt O'Leary) and kills him during an ugly, messy, unplanned fight to the death. There's a sense of justice and catharsis – hell, Bronson's Kersey never actually caught the guys who attacked his wife and daughter – but it comes with multiple costs.

First up is the psychological, as Nick's action breaks him even further emotionally. Wan shows him washing the blood off, accompanied by a haunting score, before collapsing to the bathtub's edge while crying. It's a devastating moment as we realize he isn't simply another tough guy getting revenge – he's a human being whose taking of a life has threatened his own, both physically and emotionally. This isn't going to be a slick action film. It's going to be clumsy and raw as a desperate man trades everything he has left to seek revenge for something already gone. His collapse deflates our own sense of satisfaction, and it's an unusually welcome feeling as the surface-level action "fun" is joined by something weightier and mean.

Second is more physical punishment as the spinning wheel of violence comes back around to him. The remaining ruffians, led by Billy (Garrett Hedlund), take their turn and strike back at Nick, leading to more losses on both sides. Like in Steven Spielberg's masterful Munich, we're forced to watch and root for a good guy in a fight against evil with the unfortunately omnipotent understanding that he's simply contributing to a perpetual motion machine fueled by pain, suffering, and blood. For each battle he "wins," there remains a war he never will.

It's undeniably a far heavier and supremely depressing take on the whole vigilante sub-genre, and no one should have been surprised that general audiences responded unfavorably. That's no knock as they're understandably looking for escapism and satisfaction in their infrequent jaunts to see action movies at the theater, but the critical drubbing is harder to defend. Wan pairs the film's themes with style and viscerally constructed set-pieces making for a visually striking feature, but the violence typically chooses brutality over simply looking cool. Furniture and flesh break and bleed with abandon, and we also get a sweaty, sketchy John Goodman as Billy's even more vile nightmare of a father! The whole thing is a grimly entertaining experience that shifts effortlessly between adrenaline rushes and kicks to the heart.

The film recasts the Death Wish formula with an understanding that while our impulses may disagree, violence simply cannot be the answer to every problem. It's not a sexy realization and won't leave you feeling particularly good about the world, but it's no less important for its undesirability. Sometimes entertainment hurts.

It turns out the title Death Sentence isn't meant as some snarky, '80s action movie phrase regarding the bad guys' fates – it refers to Nick's sentencing of himself. The murder of his firstborn son is a tragedy, but pursuing vengeance well beyond reason and his capability opens the floodgates to something even worse. "Sometimes it's just chaos," he says by way of belated understanding, and sometimes it's chaos of our own making.