'Westworld' Spoiler Review: 10 Questions From "The Adversary"

Last week, Westworld spent the bulk of its time within the park itself (and likely within the show's past), following Dolores and William as they ventured toward the Maze and had a bloody, empowering Wild West adventure. This week compensated by shifting the focus to park operations (and likely in the show's present), offering up corporate espionage, horrifying malfunctions, and an overwhelming sense of dread. As we do every week, let's try to answer 10 questions (some literal, others rhetorical) from "The Adversary."

Who Is "The Adversary"?

One of my favorite aspects of NBC's late, great Friday Night Lights was how the title of each episode acted as a thematic thread that tied together every subplot, a header under which every storyline could co-exist. Knowing the title of the episode you were were watching allowed you to better appreciate the elegance of the title and how some subplots acted as direct responses to others, how a B storyline could reflect the A storyline. While Westworld's titles tend to be be more straightforward, generally describing a concept or plot device on display in the episode, "The Adversary" is noteworthy because its title could easy be referring to one of a number of characters or concepts.

Is the Adversary the Man in Black, our science fiction cowboy riff on Milton's Lucifer, doing great evil in the name of potential good? Or is it his new traveling companion, Teddy Flood, who revealed a gruesome new side of himself this week? It could even be Wyatt, the new character cooked up specifically to keep the Man in Black from reaching the maze, a villain whose handiwork feels like it was torn from a horror movie.

Then again, the adversary could exist outside of the park proper. It could refer to Theresa Cullen, who has been stealing data from the park via a reprogrammed host. It could be corporate newcomer Charlotte Hale, whose arrival suggests that Westworld is about to undergo a few significant changes.

Or the title could be announcing the arrival of the greatest threat the park has seen yet: a reprogrammed Maeve. Whether she turns out to be a hero or a villain or something in-between, the park has never faced a greater threat. Then again, the adversary of the title could be humanity, who created Maeve and subjected her to countless traumas over the years. In a show where every character straddles a shade of grey, she is one of the few people allowed to see the world in black and white.

Hell, the adversary could be Arnold, whose ghost continues to hang over the park and infect the inhabitants in surprising and unsettling ways.

I don't think there's a right answer here. There's no easy fill-in-the-blank. While "The Adversary" is a chapter in a heavily serialized narrative, it's about betrayals we find in others and within ourselves. Each story thread is connected by the discovery of evil, whether it be mundane or extraordinary, programmed or natural, a plot twist or something everyone could have seen coming. Everyone finds a new demon to face in "The Adversary." The system is failing.

Does Anyone Else Not Quite Buy Sylvester and Felix?

Westworld is a smart show: elegantly written, meticulously constructed, and filled with actors doing stunning work with material that has no right to work as well as it does. And that's why the characters of Sylvester and Felix, the park technicians who find themselves roped into assisting Maeve, are so frustrating. More than anyone else on the show, they seem to exist just to force one particular storyline forward with no regard for whether or not it actually makes sense.

The fault lies not with actors Leonardo Nam or Ptolemy Slocum, both of whom manage to embody the blue collar worker of the distant future – men whose jobs are impossibly advanced, but who are essentially looked upon as little more than janitors. The fault lies in the writing, which forced these two into conflict for reasons that could have been clearer and then trapped them in Maeve's web by transforming them into dummies. It's hard to buy that these two guys would willingly engage a malfunctioning host and cater to her whims rather than report this genuinely insane and monumentally dangerous event to their superiors. Their fear for the careers just doesn't hold water at this point, especially since their transgressions would look minor when compared to the problem they have uncovered.

The truth is that their storyline feels reverse engineered: the Westworld writer's room concocted several of the best scenes in the series so far and both required Maeve to have two human park employees to act as tour guides. The effect is Westworld at its best, but the cause is the show at its weakest.

Is Maeve's Tour the Best Scene in Westworld So Far?

Once we accept that that Felix and Sylvester are simply going to dummies for the sake of advancing the plot, we can focus on what may be the strongest and most unsettling sequence in Westworld so far: Maeve's tour of the labs where the hosts are created. Guided by Felix, she walks the sterile hallways where she was manufactured and programmed and where her mutilated corpse has been dumped countless times before. She rides escalators through endless floors of nightmares, images that are impossible for us and traumatizing for her.

We witness the basic creation of the hosts, who are 3D-printed and dipped in vats until they form a white mannequin, the basic template of something that will, at some point, transform into a human being. We see the "birth" of a host, as one of these pale husks is literally injected with life – color comes to the skin, radiating out from a heart that has just begun beating.

And then our walking tour through this fluorescent hell continues to programming, a level of bizarre imagery, where the mundane becomes frightening, where the erotic might as well be rendered in ones and zeroes. Programmers walk their artificial buffalo, deer, and horses in circles, painstakingly working to ensure that the look like the real thing. Programmers work their daily grind, tapping away at their tablets as Hosts who look like flesh and blood argue and fight and make love. The entire human experience, Maeve's entire experience, is the work of artists and technicians, men and women dedicated to creating the illusion of life. Heaven exists and it's a theme park lab. But it looks a lot like Hell.

This sequence is remarkable because it's so frightening, because it taps into the existential dread of existence, because it reflects the fear that you have no control over your destiny. Maeve seeing her dreams in a Westworld commercial, a pitch-perfect pastiche of theme park advertising, is haunting. She does not own her existence. She does not make her own choices.

But above all else, this sequence is remarkable because its imagery, surreal and impossible and even darkly funny at times, could only exist on Westworld.

Who is Theresa Cullen Working For?

A few weeks ago, park programmer Elsie Hughes investigated a stray host wandering off his loop. Last week, she discovered that he was programmed to walk to the edge of the park to communicate with a satellite and release stolen data. This week, we seemingly discovered the culprit behind this corporate espionage: Theresa Cullen, the head of park operations, Bernard Lowe's not-so-secret lover, and a woman whose loyalty to the park has seemed shaky since episode one.

So, who is Theresa working for? What is she hoping to accomplish? How long has she been stealing park secrets? We do see her having a conversation with an unknown man speaking in Chinese and it's surely no accident that we don't see his face or know the nature of their conversation.

But let's not indict Theresa quite yet. While this is certainly not a good look, the fact that she's using a satellite belonging to Delos, the company that owns Westworld, may indicate that she's spying on the park to save the park. For all we know, Delos has Theresa working undercover, smuggling data and stealing secrets that Dr. Ford otherwise wouldn't reveal. We already know that the Delos board is unhappy with the park's increasingly erratic park co-founder and he's gone to great lengths to mask his intentions with his ambitious new narrative. Is it so hard to believe that she's just been quietly gathering evidence as part of an internal plot to oust Ford from the company?

Arnold Couldn't Be Alive, Right?

To paraphrase Charles Dickens: Arnold was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. But like the specters who haunt Dickens' A Christmas Carol, the deceased co-founder of Westworld has reared its head to plague his old partner, to throw his life into disarray, to meddle in his affairs and, maybe, to show him the error of his ways.

The ghost of Arnold revealed itself twice in "The Adversary," once to Elsie as she investigated the corporate espionage occurring within the park's borders and once to Dr. Ford as he saw his bizarre corner world he built within his larger fantasy world start to crumble. The former supplied us with one especially useful nugget of information: the same old relay that Theresa was using to reprogram older hosts was also being activated by Arnold...or at least someone (or something) pretending to be Arnold. Pick your fan theory poison: is Arnold's consciousness lingering around the park as some kind of artificial intelligence? Is he haunting another host, having taken control of another form as part of a trans-humanist experiment gone horribly right?

Pick your fan theory poison: is Arnold's consciousness lingering around the park as some kind of artificial intelligence? Is he haunting another host, having taken control of another form as part of a trans-humanist experiment gone horribly right?

But it was the latter that proved more disturbing and may offer a deeper look at what Arnold's intentions could be. After discovering the death of the Host built to resemble his childhood dog at the hands of the Host built to resemble his childhood self, Dr. Ford does some analysis and determines what we've suspected: that disembodied voice some hosts have been hearing, the one that has been allowing older Hosts to break out of their loops, does belong to Arnold...and he's seemingly declared war on Ford. As the young Robert Ford relays to his human self, he put the dog out of its misery because is was killer – he was doing it a favor by ending its life and preventing him from hurting anyone else. It's a cryptic message, but it can't help but feel like a threat. After all, Ford, our resident Old Testament God, has built a playground of killing and violence, where every Host is a potential victim for paying customers. Maybe, Arnold seems to be implying,

As the young Robert Ford relays to his human self, he put the dog out of its misery because is was killer – he was doing it a favor by ending its life and preventing him from hurting anyone else. It's a cryptic message, but it can't help but feel like a threat. After all, Ford, our resident Old Testament God, has built a playground of killing and violence, where every Host is a potential victim for paying customers. Maybe, Arnold seems to be implying, it's time for him to be put down for the good of the world he won't stop tampering with.

Who Attacked Elsie?

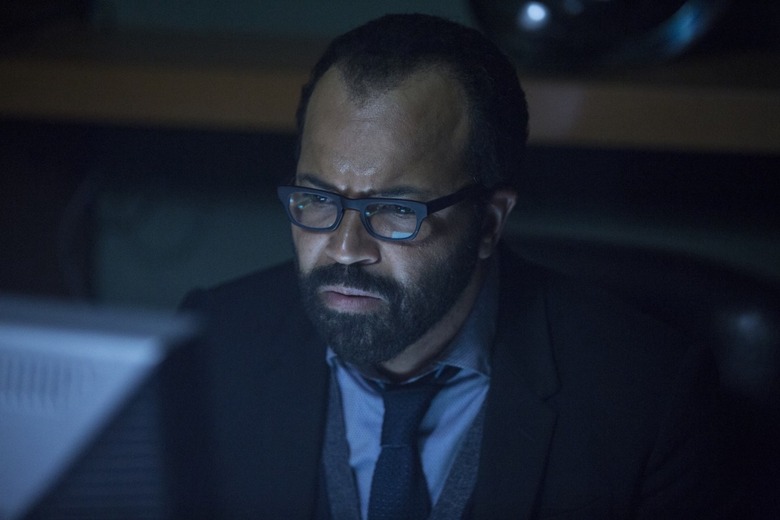

On a show that has occasionally struggled to create characters who connect with us beyond their usefulness to the plot, Shannon Woodward's Elsie Hughes has increasingly become the secret weapon of the show's ensemble cast. While Evan Rachel Wood and Thandie Newton have done tremendous and technically challenging work as robots undergoing an awakening (not to mention Ed Harris and Anthony Hopkins just doing their thing), Woodward has put a human face on park ops.

Bernard Lowe keeps his cards close to his vest. Theresa Cullen is icy by design. Lee Sizemore is a prick. Ashley Stubbs is a macho goon. But Elsie? She's funny and sarcastic and just smart enough to take the lead while just enough in the dark to encourage her to ask questions. If Dolores provides our point-of-view in the park itself, Elsie provides out point-of-view in park ops. She's a fun character on a show where every is a little too grim, a source of humor in a show that is focused on big, dramatic questions about humanity and art and violence. Watching her investigate that relay in a dark and creepy theater is a highlight of "The Adversary." She's not one to avoid a decent quip or say exactly what the audience is thinking.

And someone has attacked her and her fate is unknown and oh-my-God Westword, you better not kill Elsie Hughes because I didn't realize how important she was to this show until this very moment.

As for who attacked her, there is literally no evidence. This section was really just an excuse to praise Woodward.

How Heartbreaking is Teddy's New Backstory?

It's been a few episodes since James Marsden's Teddy Flood has died, but his ongoing existence has only found a way to become more depressing. What's worse? Being an empty slate, a square-jawed Ken doll who doesn't have a past because the Powers That Be determined that you weren't important enough o have one, or being a tortured murderer with connections to a genuine monster and serial killer whose past actions fill your with regret and anguish.

The Teddy Flood we met back in the pilot would never have murdered so many men in cold blood and he certainly would have never stood behind a chain gun and wiped out an entire camp of union soldiers. The Man in Black, his unlikely traveling partner, notes that his new programming has give him more vinegar, an amusing way to describe an injection of evil into a Host who was created to be a pure white hat.

In any case, the subplot involving Teddy and the Man in Black didn't go too far this week, offering an excuse for a bloody action scene and providing more evidence that Wyatt is Ford's most monstrous Westworld creation yet. Even the jaded Man in Black seems impressed by the carnage he's leaving in his wake. However, the appearance of the Maze on that brand wielded by that Union soldier confirms that this odd couple are still on the right track to their goal and, as always, they're leaving a trail of bodies in their wake.

What Kind of "Transition" is Charlotte Hale Overseeing?

From the moment Charlotte Hale appeared at the Mesa Bar to shrug off Lee Sizemore's gross advances, it's clear that she was more than just a guest. After all, you don't hire someone as great as Tessa Thompson for your show unless you're prepared to give her something to do.

And something appears to involve her overseeing some "transitions." Because Charlotte Hale is the "executive director of the board," the kind of title that implies she has the power to make sweeping changes with the snap of a finger. We've known for some time that the Delos board wasn't happy with certain aspects of Westworld and it looks like they've started make their move in this corporate chess game. Dr. Ford's decision to push back, to create his own narrative and scrap everything that was already in the works, has invited a return shove from the parent company. What Ms. Hale intends to do to the park and how she intends to handle the fallout remain unknown.

But hey! Tessa Thompson is on Westworld! If you haven't, you should go watch Creed and Dear White People so you too can be excited about her presence on the show.

Is Dr. Ford a Criticism of Nostalgia Culture?

One of Westworld's quiet strokes of genius involves the normalizing and the aging of thoroughly modern concepts that are still impenetrable to the majority of people alive in 2016. It's impossible to imagine the 78-year old Anthony Hopkins sitting at a computer and writing code, but that's just exactly what Dr. Robert Ford does every single day. In 50 years, the modern tech hotshots of the day will be old men, albeit old men who know how to craft complex systems to make computers and machines (and robots?) function. It's difficult to imagine an 80-year old Mark Zuckerberg, but Westworld invites you to try. Our generation will grow old and it will carry our very specific skills and baggage with it.

Westworld also invites us to view another trait through the lens of age: childhood nostalgia. While affection for the past has always been a thing (how many times have your grandparents shared stories from days gone by?), our love for our childhood obsession have ballooned in recent years. It's why there's an entire industry of films and television shows being made that recreate the Amblin feeling of the '80s. It's why old properties are being reimagined as massive blockbusters. It's why I've spent an unhealthy amount of time watching old toy commercials on YouTube. We live in an era where corporations cater to our nostalgia, where our memories continue to live on via television and and movies and Buzzfeed lists about things that only '90s kids would know. We have decided that this is okay. It feels good.

But it may also be a little unhealthy. Case-in-point: Dr. Robert Ford's off-limits corner of Westworld, where one of his only happy childhood memories has been exactingly recreated. Hosts acting as Ford's younger self, brother, father, mother, and dog all live within this physical flashback to another time, acting as a personal place for the park's aging creator relive his past. Although this space was created by Arnold as a gift for his partner, Ford has spent the decades obsessively tweaking it, making it more accurate, removing the rose tint that the dead co-founder of Westworld had installed.

Ford, a futurist who has pioneered technology and entertainment in ways that boggle the mind and imagination, is stuck in the past. He can control armies of hosts with a single phrase or gesture. He can modify the world around him on a whim. His decisions affect the lives and work of countless employees. And yet, he spends his time in his own head, stuck in the past and tethered to a childhood that he can never let go. Even God can't stop thinking about the good 'ol days. Even God wishes he could go back in time.

How is Maeve Going to Break the Game?

Westworld has never been shy about adopting the language of game systems and "The Adversary" continues suit. Maeve's "attribute matrix," the system that determine certain core aspects of her personality, should be familiar to anyone who has played a pen-and-paper RPG or a video game that utilizes similar mechanics (like Skyrim or Fallout 4).

In those games, a character is built by assigning points to various categories, but players are only allowed a certain number of points to distribute as they see fit. If you want your character to be physically strong, you may have to sacrifice some dexterity. If you want your character to be highly intelligent, you'll have fewer points to inject into charisma. Some players may put all of their points in a few categories while others will attempt to distribute them as evenly as possible, creating a character who is pretty good at everything without being exceptional at anything.

I think about these attribute systems often, sometimes when I'm playing Dungeons & Dragons with my gaming group and sometimes when I'm lying awake at night and thinking about the infinite abyss of the universe and letting my stomach fill up with dread. I created a fantasy adventurer who only exists on paper and in a tiny metal figurine. I decided who he was. I determined his strengths and weaknesses. I set his limits. He has no agency and no potential to better himself at certain things because I decided how I wanted to play him. During those nights when I can't sleep and just stare at the ceiling, I wonder if a larger force has done the same for me.

When Maeve demands that Felix and Sylvester modify her attributes, she's breaking the game of Westworld. She's demanding to be made into an unbalanced character, someone who can ignore the boundaries that were put in place to ensure that everyone has a good time. Her modifications make for a frightening cocktail: her pain and loyalty attributes are lowered, but only after someone with higher access has already increased her paranoia and sense of self preservation (a mystery that will be surely addressed down the road). Then the episode ends with an infuriating (in the best possible way) cliffhanger: Maeve's "bulk apperception" is maxed out, effectively making her more intelligent than any of the humans who built her.

"We're going to have some fun, aren't we?" Maeve says with a mischievous grin. But her definition of fun is surely different than ours. After all, attributes are limited in RPGs for a reason: if you break the rules and build a character beyond the limits, you can blow through your enemies, tackle all threats, and solve all problems without breaking a sweat. There are no challenges. It's no...well, fun. But this isn't a game for Maeve. This is her life. And she just broke the rules.

Everything Else That Couldn't Be Phrased as a Question