HDTGM: A Conversation With Randall Frakes, Writer/Producer Of 'Hell Comes To Frogtown'

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

In 1978, a pair of young, wannabe filmmakers made a 12-minute, 35mm short called Xenogenesis. One of those wannabes was a visionary artist by the name of James Cameron. The other—who Cameron calls "the best kept secret in Hollywood"—was a precocious storyteller by the name of Randall Frakes. Over the following four decades, the two have collaborated on several projects. But one project that did not collaborate on—though they came close to doing so—was a subversive, sci-fi B-movie called Hell Comes to Frogtown. That one was written solely by Randall Frakes, though the final film stayed significantly from his initial vision. To figure out what happened, I spoke with Randall Frakes about cyborgs-turned-assassins, wrestlers-turned-actors and the underappreciated unity of opposites.

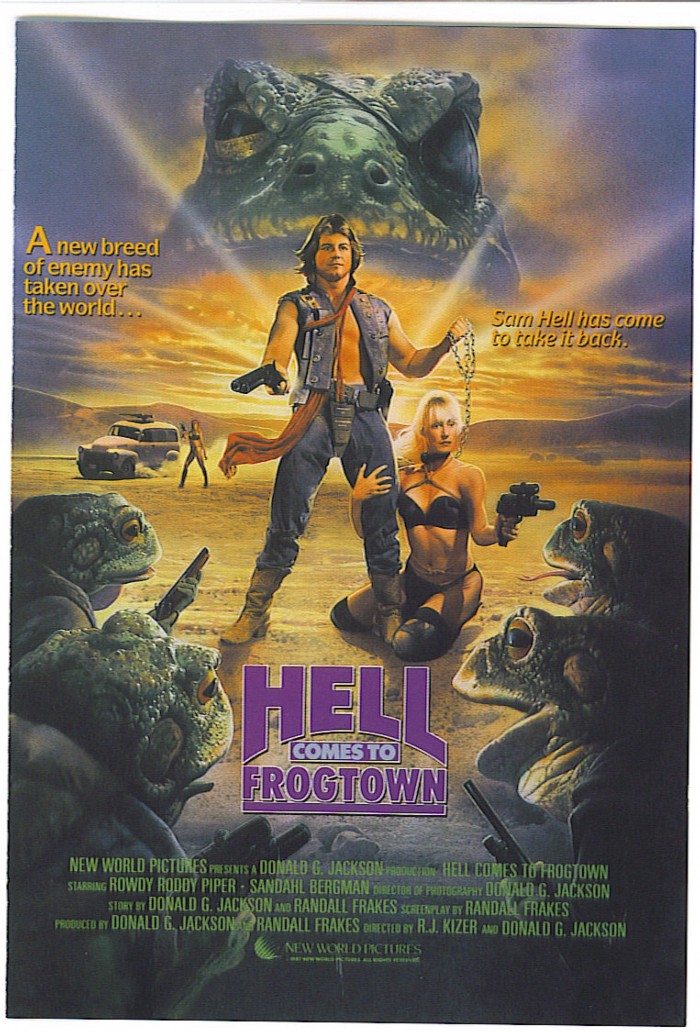

Hell Comes to Frogtown Oral History

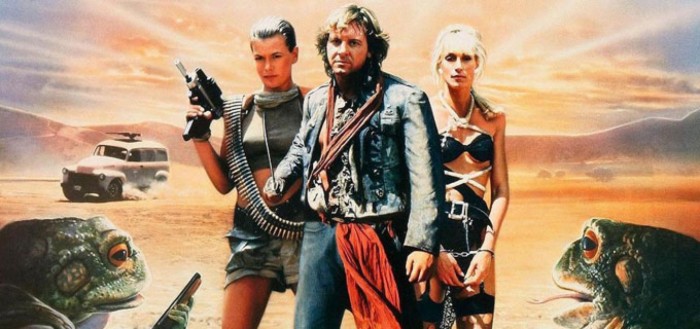

How Did This Get Made is a companion to the podcast How Did This Get Made with Paul Scheer, Jason Mantzoukas and June Diane Raphael which focuses on movies This regular feature is written by Blake J. Harris, who you might know as the writer of the book Console Wars, soon to be a motion picture produced by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg. You can listen to the Hell Comes to Frogtown edition of the HDTGM podcast here. Synopsis: In a post-apocalyptic wasteland—where fertile women are rare and fertile men even rarer—a nomadic outlaw named of Sam Hell must infiltrate the mutant city of Frogtown to rescue a collection of fertile females.Tagline: A New Breed of Enemy has Taken Over the World...Sam Hell has Come to Take it Back.

Part 1: Whatever that Was, I Want to Do It TooBlake Harris: So, before Terminator and True Lies, before you ever even dreamed about bringing Hell to Frogtown, you grew up in Brea, California. I was curious if, as a kid, movies were a big part of your universe?Randall Frakes: Oh yes. When I was six years old, I collected Classics Illustrated comic books. And I would cut out the colorful covers and tape them up outside my bedroom to pretend that my room was a movie theater.Blake Harris: And what would be screening at the Little Randall Frakes Theater? What movies meant a lot to you as a kid?Randall Frakes: The first movie I remember seeing was Robert Aldrich's Attack, a grim World War II movie starring Eddie Albert and Jack Palance, in which Palance gets his arm crushed when a German tank runs over it. But he doesn't die. He comes back to kill his cowardly officer who got his men killed. It was black and white, standard aspect format and mono, but something about it screamed out: important truths about human nature and there is no Santa Claus!Blake Harris: [laughing]Randall Frakes: I felt empowered with a life truth. I felt freed from the cloying nightmare of childhood myths. I said to myself then and there: Whatever that was, I want to do it too. And that was the beginning.Blake Harris: Given that you were so young, how did you actually go about figuring out how to "do it too?" And were your parents supportive of this passion? Were they active moviegoers?Randall Frakes: My father had been an actor; in features an extra, and in early TV part of a troupe that acted out famous scenes from famous books on a game show. He loved movies and acting, so once I got the bug to pursue my exploration of movies, he supported me 100 percent. I studied '30s classics on TV and realized that every good story, technique and characterization had already been done in that time and everyone was just recycling them in the '50s. By the time I was a freshman in high school, I was working in the local cinema, buying and listening to soundtrack music, and reading dozens of books on the making of the movies I was watching.Blake Harris: Had you begun to film anything yourself?Randall Frakes: When I was a junior in high school, I started making short films in 8mm. Some of them got shown at the local theatre at the head of the main movie.Blake Harris: Do you remember what they were about, or what they were like?Randall Frakes: My most ambitious short was about 15 minutes long. It was called Trek. Heavily influenced by the original Planet of the Apes movie. It was about a caveman trekking through wilderness to find new sources of food, being suddenly confronted with the ocean, which terrifies him and makes him run off without direction, until he comes to a modern factory on the horizon. It freaks him out, and he turns to run in another direction and is suddenly frozen with fear, standing by a highway with modern cars roaring past. He lunges to get across and is struck by a car. He lies dying, looking up at the driver coming over to check him. The driver was the twin brother of the actor playing the caveman. So he looks just like him (except he didn't have long hair and a beard and was wearing a suit). It was my visual poem saying that primitive man is being killed off by modern technology. Not particularly brilliant and basically silly, but...Blake Harris: ...definitely more impressive than anything I was writing at that age. And I assume you edited these films yourself?Randall Frakes: I did. The films I made back then were, mostly, exercises in editing. [laughing at a memory] My last editing experiment was to shoot footage of this really beautiful but very straitlaced sophomore, coming back to her bedroom in a tennis outfit. I got her to lie on the bed and had her slowly massage her calves and thighs. All very innocent. Then I shot more footage with another girl—a much more liberal and raunchy girl with a similar body—touching herself more erotically, indicating masturbation. I didn't show the raunchy girl's face, only inserts of her touching herself, cut into the wider shots of the straitlaced girl. But when I showed it to some of my male friends, they never suspected a body double. They couldn't believe I had gotten that straitlaced girl to touch herself on camera! That was one of the biggest eye-openers about the power of editing, how even with a documentary you could fool an audience. I was around 14 years old when I made that masturbating movie. I was following in Spielberg's path...but deviating a little into Russ Meyer territory!Blake Harris: [laughing] But I suspect you had to shelve those dreams for a little while because, after high school, you went into the Army. I read that while you were in the Army, you edited a military newspaper. Is that accurate? How did that come about?Randall Frakes: I volunteered for certain jobs in the Army that would help me avoid shooting at anyone or getting shot at. I signed up for—and first went to—South Korea, and then West Germany. In West Germany, I became a reporter/editor of a company-sized newspaper that was supposed to just be a propaganda rag to reassure the parents of the new recruits by writing stories about their safe arrivals, how well they are being treated and how safe they will be while doing their duty for their country. All pretty much bullshit. By that point in my life, I was all about exposing bullshit for what it was.Blake Harris: In what sense?Randall Frakes: I started going undercover to reveal corruption and malfeasance by the officers in the companies nearby. When I went undercover at Mannheim Stockade to investigate gross prisoner abuse, I found the evidence and published it in my little rag, which created a shitstorm of controversy. Got the warden demoted and removed and caused my superior officer to want to kick me out of the Army with a dishonorable discharge. I told him I would love a trial in which I could officially air my claims of corruption and maltreatment of soldiers. He promised to screw me over terribly.Blake Harris: Did he?Randall Frakes: Well, a few months later, he summoned me to his office and tossed a thick envelope at me. He told me to open it outside. I thought: Okay, at last, my summons to my court martial. But no. The package contained a framed award.Blake Harris: An award?Randall Frakes: From the Army's official newspaper for Europe—Stars and Stripes—awarding me best investigative story of the year. And now, obviously, I couldn't be kicked out dishonorably for something the Army was awarding me for.Blake Harris: That's awesome. But let's go back for a second to the actual undercover work. What was that experience like for you?Randall Frakes: Some prisoners thought I was a stooge for the warden, trying to get prisoners to go on record with their complaints so he could punish them later. One big prisoner broke off a plastic fork so the handle was sharp and held it up against my throat, saying that if I didn't convince him I was on the level, he would cut my carotid artery and within a minute I would be dead on the floor in a pool of my own warm blood.Blake Harris: Wow. Oh wow. So what did you say?Randall Frakes: I couldn't think of a thing to say! Fortunately, another prisoner from my company recognized me and stayed his hand. So one of the lessons I learned from that experience is that we need investigative reporters and other truth-diggers to out injustice and corruption...but you could get killed doing that. So I thought: What would be a safer way to tell truths? Fiction!Blake Harris: ...and a writer is born.Randall Frakes: A screenwriter. Okay, I thought, I'll write movies. Movies about socially relevant subjects that needed public airing. Get paid a lot of money, instead of getting investigated by a government agency or losing my carotid artery.Blake Harris: Wise decision, I'd say. And, if I have my chronology correct, one that would soon lead to you meeting a likeminded guy by the name of James Cameron? Part 2: The Genesis of XenogenesisRandall Frakes: James Cameron tried to pick up my girlfriend in psych class at City College. That's how I met him. She brought him over to meet me because, as she said, "we talked the same talk." I broke up with her months later, but have been a collaborator and friend to Cameron ever since then.Blake Harris: Was it friendship at first sight?Randall Frakes: Basically I knew within two sentences that this guy was not only on the same page as me, but a genius. It was clear as could be. Jim has always had an extraordinary mind. Not a perfect person, mind you (who is?), but definitely miles above the average joe in strategic and conceptual thinking. And we shared similar tastes; he was a movie fan and a sci-fi book fan. Our big difference was he was always a hard-line scientist guy with a Darwinian social bias. In his mind, living life is like waging a war with fate, and only the strong survive. I was always more of a surf-the-wave type of guy. We milk the cow, not slaughter it. Symbiosis, not competition. Both survival strategies have been shown to work in nature. But he was always more focused and ambitious than I. He had written the first part of a novel that was extremely mature and brilliant. He was also a good amateur sculptor and artist. I knew this guy was bursting with talent and hundreds of brilliant ideas. So I told him he should be a film director, a job that required all his talents. He asked how to become a director.Blake Harris: Ha! What did you say?Randall Frakes: I said, "Write a script that's so good everyone in Hollywood wants it, and then attach yourself as the director." He said that he didn't know how to write screenplays. I told him he knew story very well. Learning how to tell a story in script format would only take him a few weeks at most to learn. So I suggested we write a script together. That script became Xenogenesis.

Part 2: The Genesis of XenogenesisRandall Frakes: James Cameron tried to pick up my girlfriend in psych class at City College. That's how I met him. She brought him over to meet me because, as she said, "we talked the same talk." I broke up with her months later, but have been a collaborator and friend to Cameron ever since then.Blake Harris: Was it friendship at first sight?Randall Frakes: Basically I knew within two sentences that this guy was not only on the same page as me, but a genius. It was clear as could be. Jim has always had an extraordinary mind. Not a perfect person, mind you (who is?), but definitely miles above the average joe in strategic and conceptual thinking. And we shared similar tastes; he was a movie fan and a sci-fi book fan. Our big difference was he was always a hard-line scientist guy with a Darwinian social bias. In his mind, living life is like waging a war with fate, and only the strong survive. I was always more of a surf-the-wave type of guy. We milk the cow, not slaughter it. Symbiosis, not competition. Both survival strategies have been shown to work in nature. But he was always more focused and ambitious than I. He had written the first part of a novel that was extremely mature and brilliant. He was also a good amateur sculptor and artist. I knew this guy was bursting with talent and hundreds of brilliant ideas. So I told him he should be a film director, a job that required all his talents. He asked how to become a director.Blake Harris: Ha! What did you say?Randall Frakes: I said, "Write a script that's so good everyone in Hollywood wants it, and then attach yourself as the director." He said that he didn't know how to write screenplays. I told him he knew story very well. Learning how to tell a story in script format would only take him a few weeks at most to learn. So I suggested we write a script together. That script became Xenogenesis.

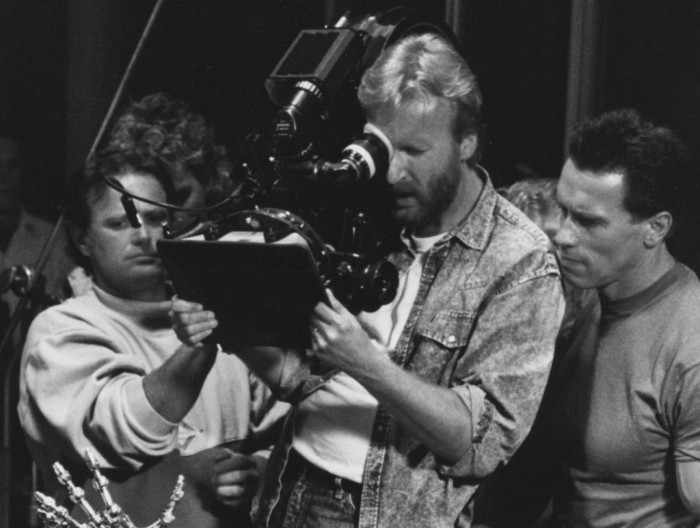

Blake Harris: Was your assumption accurate? Did he take to it naturally?Randall Frakes: To his credit, he immediately got it. And except for too verbose dialogue here and there, the script was damn good. It was based on a short story I had written and published a few years before called "I Wince in Limbo." But after Jim got his mind wrapped around it, he morphed it into a seedbed for all the basic ideas that would appear in most of his later movies in more mature form. For example, in Xenogenesis, there is an auto-maintenance robot that is the only survivor on a planet of beings who became extinct because they became addicted and trapped in digital reality states. The robot design was reused for the hunter-killer tanks in The Terminator future scenes.Blake Harris: That's so interesting. From page to screen...just 10 years later. But tell me a little bit about the part not on the page. I've cowritten scripts before, and that relationship between writers is always unique. What was this was one like? Were there any early hiccups to what obviously became a long-term and fruitful relationship?Randall Frakes: Most challenging were the moments when I had a different idea than Jim and had to argue with him. Because although he was learning from me and would listen carefully, he got locked into doing some things his way. The only way to change his mind was with impeccable logic, which I was not used to having to do at that time. So, while I was teaching Jim how to write a movie, he was teaching me better ways to argue!Blake Harris: Ha! Symbiosis!Randall Frakes: Yes, but I will also say that Jim was so brilliant and so ambitious that once he got the idea into his head to become a film director, he would have found a way in with someone else, or all by himself.Blake Harris: What did you guys do with the script after it was finished?Randall Frakes: Well, the plan was to make a 15-minute demo film illustrating a dramatic scene from the Xenogenesis script. It was supposed to be used to raise funds to make the entire script into a feature film. First, Jim and I made a 16mm demo film showing the Xenogenesis spaceship he designed flying past a star field. We didn't have a level studio floor (just my garage), so the ship looked a lot like a goose bouncing up and down, flapping its fins. Hilarious. And we also shot a laser pistol chase.Blake Harris: How did you go about doing that? Logistically, I mean.Randall Frakes: We shot the fight in a cement storm channel, so it looked futuristic. And we had squibs we made ourselves wired to go off when there was supposed to be a hit. We shot it all in reversal stock and then Jim—using an X-Acto blade—literally scraped off the emulsion to create a clear line, which when projected looked like a laser beam!Blake Harris: Were there other scenes you needed to film? Or did those two make up the entire 15-minute demo?Randall Frakes: Oh, no, no. There was still a lot more. But in order to film the rest of our demo, we ended up needing help from the dentists...Blake Harris: The dentists?Randall Frakes: The Orange Country dentists.Blake Harris: The Orange County dentists?!Randall Frakes: [laughing] So another friend of mine who owned his own recording studio at the time had been hired out by a garage band headed by a kid whose father was an investment advisor to this gang of dentists from Orange County.Blake Harris: Ah, the Orange Country dentists!Randall Frakes: When the kid saw the 16mm footage, he told his father, who asked to see what we had shot. He liked what he saw and then called us in to talk to the dentists, who had exactly $17,000 left to invest and the fiscal year was about to end. So they needed to invest in something fast and they picked us.Blake Harris: Amazing.Randall Frakes: We shot the Xenogenesis demo film in an industrial unit, much like the one used by the effects team on Star Wars. We decided on making the film about that particular scene because it was all action, and we could do it with stop-motion, which we both wanted to experiment with. We also only needed two actors. The writer William Wisher—a friend and future collaborator—was one of them. Not only did he have squibs blow up on his leg, but also had to really dangle from a two-story building to get the angles we needed. He was a real trouper.Blake Harris: You had made films before, but never on this level, so I'm curious what the experience was like for you.Randall Frakes: It was backbreaking, grueling work that took up six-day weeks, over twelve hours a day. I didn't mind the effort, but I found it tedious in the extreme—which is why I am content to be a writer/producer only. Directing is the most horrendous job in the film industry, and anyone who can pull it off with panache deserves all that money and fame.Blake Harris: Haha. So you said earlier that the plan was to make this 35mm short in the hopes of funding a feature-length film. What happened with that?Randall Frakes: Unfortunately, the dentists did not know how to use the movie to get big investors. So Jim and I used it as a demo film to get us work as effects technicians, simply as a way to break into the business. Since the principal effects technique on display in the demo film was stop-motion, we actually got an offer to animate the Pillsbury Doughboy commercials. We turned that down. Ultimately, Jim found his way into Roger Corman's film factory as a modeler and told me that although the pay was less, it was a more direct path to making movies ourselves.Blake Harris: If I'm not mistaken, the first Corman film you guys worked on was Battle Beyond the Stars. What were your roles on that?Randall Frakes: Jim started as a modeler, but he went on to become art director of the whole movie, doing a spectacular job with little time and almost zero money. Meanwhile, I was operating the front protection rig, many times shooting the movie with a big Mitchell rack-over camera alongside the main unit. It was a terrifying experience. Especially since the last thing I wanted to do was be a cinematographer; I just wanted to write, damn it! But you do what you have to, to get inside the industry door. Jim was always better at that than me, sacrificing now for future rewards. Blake Harris: Speaking of which, at some point around that time, he started working on The Terminator. Where you around for the ideation of that?Randall Frakes: I helped Jim in the early stages of his writing The Terminator by consulting with him and cheerleading him onward. By the time he had finished the detailed treatment, he asked me to cowrite the script with him. But I turned him down. I think he never really knew why—since I never really told him—but it was because his vision was so complete. So tight, so commercial. I thought all my ideas could do was dilute his vision. If I were to work with him on the script, I knew I needed to embrace his way of telling the story 100 percent. And since I had some reservations that he didn't like, I realized I would be an inappropriate partner. So he ended up getting William Wisher to cowrite parts of The Terminator. It all turned out fine, so it was the better decision. And the strategy worked, because it was such a good script, there was a bidding war and finally Jim found a producer, Gale Anne Hurd, and a production company that would allow him to direct his own script. And the rest is history.

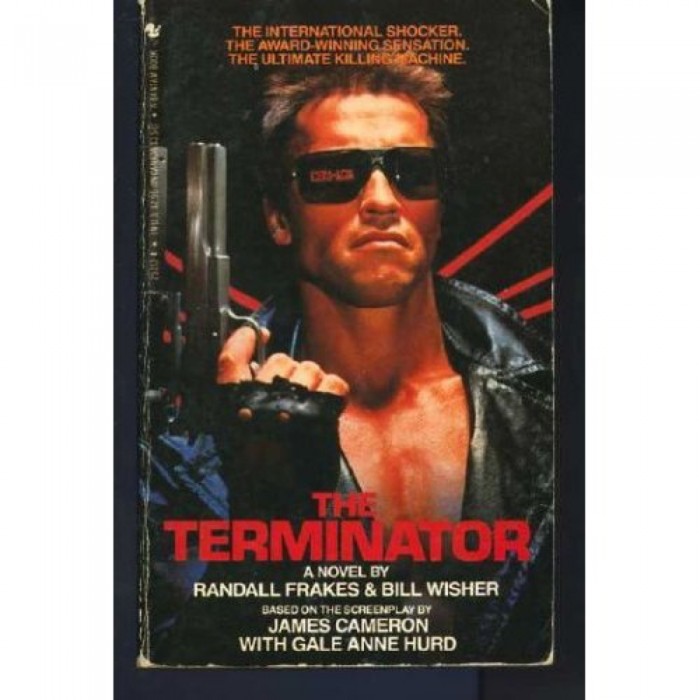

Blake Harris: Speaking of which, at some point around that time, he started working on The Terminator. Where you around for the ideation of that?Randall Frakes: I helped Jim in the early stages of his writing The Terminator by consulting with him and cheerleading him onward. By the time he had finished the detailed treatment, he asked me to cowrite the script with him. But I turned him down. I think he never really knew why—since I never really told him—but it was because his vision was so complete. So tight, so commercial. I thought all my ideas could do was dilute his vision. If I were to work with him on the script, I knew I needed to embrace his way of telling the story 100 percent. And since I had some reservations that he didn't like, I realized I would be an inappropriate partner. So he ended up getting William Wisher to cowrite parts of The Terminator. It all turned out fine, so it was the better decision. And the strategy worked, because it was such a good script, there was a bidding war and finally Jim found a producer, Gale Anne Hurd, and a production company that would allow him to direct his own script. And the rest is history. Part 3: Lukewarm Enchiladas with the So-Called Zen Filmmaker Blake Harris: Before we start digging into Frogtown, I had one more Terminator-related question. You ended up cowriting the film's novelization. What was that like?Randall Frakes: It was like the closing of a circle. I had sat with Jim—consulting on the birth of the story as a movie script—and now I was coming in at the end of the process to make a novel out of his script. If Jim had had time, he would have loved to write it himself. Because he has always wanted (and still wants) to write books. I hope when he retires from making movies that he dedicates himself to writing about science and sociology. Whatever the subject, they would be great books. His is a voice that needs to be heard in the public discourse as humanity seems to be hanging by our fingers over a precipice of our own making. In any case, Jim asked William Wisher to do the novelization, but Bill was a little leery of doing a whole book by himself. Even if it was based on a well-written and detailed screenplay. They talked about me coming on board, which made sense.Blake Harris: How did you guys go about dividing up the work?Randall Frakes: We decided that he would write the chapters on Reese and the mission, and I would write the chapters on Sarah Connor and on the Terminator. The book naturally featured split POVs of those three characters, so it was easy to split the assignment up. And it worked beautifully, because Reese has a voice that is (mostly) Cameron's Darwinian survival of the fittest, mixed with Bill's fascination with all things military and strategic, and I loved expanding on Sarah's character in the book. I became her to a slight degree. In many ways, she represented Jim's softer, more nurturing side: Jim can be the sweetest, most generous human being on the planet...but threaten his family or his work and watch out! So, for me, the most interesting part was expanding Sarah's background from the movie: tapping into the female side of my personality, without warping her from Jim's original conception. And then, from Sarah, I'd go to the opposite extreme and write the interior states of the Terminator cyborg. Talk about Jekyll and Hyde!

Part 3: Lukewarm Enchiladas with the So-Called Zen Filmmaker Blake Harris: Before we start digging into Frogtown, I had one more Terminator-related question. You ended up cowriting the film's novelization. What was that like?Randall Frakes: It was like the closing of a circle. I had sat with Jim—consulting on the birth of the story as a movie script—and now I was coming in at the end of the process to make a novel out of his script. If Jim had had time, he would have loved to write it himself. Because he has always wanted (and still wants) to write books. I hope when he retires from making movies that he dedicates himself to writing about science and sociology. Whatever the subject, they would be great books. His is a voice that needs to be heard in the public discourse as humanity seems to be hanging by our fingers over a precipice of our own making. In any case, Jim asked William Wisher to do the novelization, but Bill was a little leery of doing a whole book by himself. Even if it was based on a well-written and detailed screenplay. They talked about me coming on board, which made sense.Blake Harris: How did you guys go about dividing up the work?Randall Frakes: We decided that he would write the chapters on Reese and the mission, and I would write the chapters on Sarah Connor and on the Terminator. The book naturally featured split POVs of those three characters, so it was easy to split the assignment up. And it worked beautifully, because Reese has a voice that is (mostly) Cameron's Darwinian survival of the fittest, mixed with Bill's fascination with all things military and strategic, and I loved expanding on Sarah's character in the book. I became her to a slight degree. In many ways, she represented Jim's softer, more nurturing side: Jim can be the sweetest, most generous human being on the planet...but threaten his family or his work and watch out! So, for me, the most interesting part was expanding Sarah's background from the movie: tapping into the female side of my personality, without warping her from Jim's original conception. And then, from Sarah, I'd go to the opposite extreme and write the interior states of the Terminator cyborg. Talk about Jekyll and Hyde! Blake Harris: [laughing] And so jumping ahead a few years—not quite to 2029, but to a wonderful era called the late '80s—talk to me about Hell Comes to Frogtown. You cocreated the story with a Donald G. Jackson. What was Donald like?Randall Frakes: Donald G. Jackson was an independent filmmaker. He liked to call himself a Zen filmmaker. That meant he shot 16mm movies with no script and just improvised the whole movie. In the right hands, this technique could have produced a John Cassavetes. But the most Don could achieve was something only slightly wackier and weirder than Ed Wood. To his credit, Don was a gutty guy. But his influences were underground comics and other counter-culture tropes (like Spaghetti Westerns), and he only patched them together for end effect, rather than using the techniques to serve the mood and plot requirements of the story. He was as ambitious as Jim, but without Jim's deep knowledge of storytelling and mythmaking. Don loved movies for their end effects, not their structure and plotting. That bored him tremendously. He was bored with story and I was bored with directing. A match made in heaven!Blake Harris: And how did the two of you meet?Randall Frakes: I met Don at Corman's studio when he joined the night shift team, which was basically just him and myself. We worked the midnight shift, setting up effects shots for the Skotak brothers to shoot during the day. During that time, Don and I bonded, and he talked about the kind of movies he loved and wanted to make. I kept trying to convince him that he needed good stories and characters to reach the widest audiences, but he was not so sure. Eventually, we quit Corman and Don privately financed a micro-budget post-apocalyptic weirdness called...

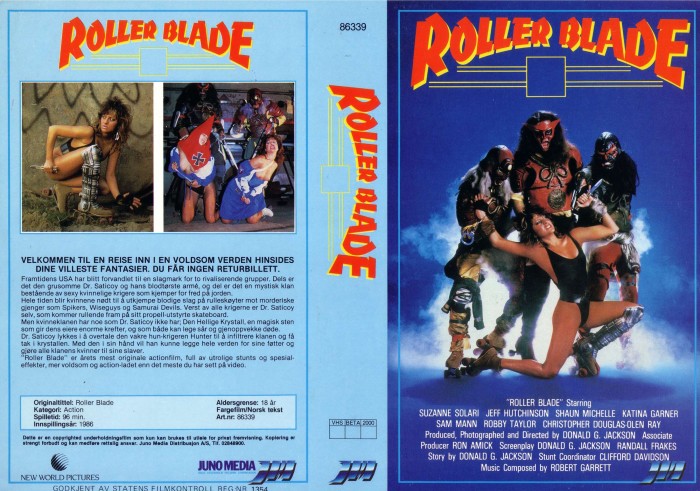

Blake Harris: [laughing] And so jumping ahead a few years—not quite to 2029, but to a wonderful era called the late '80s—talk to me about Hell Comes to Frogtown. You cocreated the story with a Donald G. Jackson. What was Donald like?Randall Frakes: Donald G. Jackson was an independent filmmaker. He liked to call himself a Zen filmmaker. That meant he shot 16mm movies with no script and just improvised the whole movie. In the right hands, this technique could have produced a John Cassavetes. But the most Don could achieve was something only slightly wackier and weirder than Ed Wood. To his credit, Don was a gutty guy. But his influences were underground comics and other counter-culture tropes (like Spaghetti Westerns), and he only patched them together for end effect, rather than using the techniques to serve the mood and plot requirements of the story. He was as ambitious as Jim, but without Jim's deep knowledge of storytelling and mythmaking. Don loved movies for their end effects, not their structure and plotting. That bored him tremendously. He was bored with story and I was bored with directing. A match made in heaven!Blake Harris: And how did the two of you meet?Randall Frakes: I met Don at Corman's studio when he joined the night shift team, which was basically just him and myself. We worked the midnight shift, setting up effects shots for the Skotak brothers to shoot during the day. During that time, Don and I bonded, and he talked about the kind of movies he loved and wanted to make. I kept trying to convince him that he needed good stories and characters to reach the widest audiences, but he was not so sure. Eventually, we quit Corman and Don privately financed a micro-budget post-apocalyptic weirdness called... Blake Harris: Roller Blade? Randall Frakes: Yes, Roller Blade, a strange, improvised conception about roller-skating nuns with healing powers trying to bring order and love back to a ravaged, brutal world. Don had also previously made a wrestling documentary called I Like To Hurt People with Andre the Giant. New World Pictures—after Corman sold it to a bunch of clueless investors—had made over a million dollars with that documentary, so they picked up Roller Blade and made a small fortune on that as well. As a result, Don was the darling boy at New World, and they asked him the question everyone struggling to get in the business wants to hear: What else you got, kid?Blake Harris: Frogtown?Randall Frakes: Well, he didn't have anything except a one-page menu list of characters and situations for a movie that, yes, he was already calling Hell Comes to Frogtown. So he takes me to a restaurant, buys me enchiladas and tells me he's been thinking about my rants about the importance of script. At the restaurant, he shoves the one-pager in front of me and says that he needs a whole script fast. For New World.Blake Harris: I don't mean to interrupt you, but I'm curious what was even on that one-page document. How much had been thought out already?Randall Frakes: Not much. There was a short description of a place called Frogtown and some details about a main character was the only fertile male in a world where there were people who looked like frogs. That was all. But I looked at it and the whole movie—from beginning to end, pretty much the way the first draft was written—just started playing in my head. I looked at the one-pager in a sorta trance for about 15 minutes, until Don said, "Uh, your enchiladas are getting cold." And I hate cold enchilada. So that's when I turned to him and said I see the whole movie. I told him I could write it in a week or less, and then I scarfed down my lukewarm enchiladas.Blake Harris: And what did he say?Randall Frakes: He didn't believe me. But he told me if I did manage to write it in a week, he'd pay me a $500 bonus. To make sure I didn't somehow cheat, he sat alongside me while I typed the first draft of Hell Comes to Frogtown. It was pure stream of consciousness stuff—something I've never been able to repeat—and it resulted in a script 120 pages long.Blake Harris: How similar to the actual film was that first draft?Randall Frakes: [The draft] was a lot raunchier, which in my view was almost a Hallmark card post-apocalyptic movie! For example: In the beginning, when we first see Sam in his cell, he's masturbating. Just to show his absolute disdain for authority, his belief in living life to the fullest (no matter where you are) and also to introduce Sam as a "loaded pistol," always ready to fire. There was also a scene, later in the movie, where the Head Frog, Commander Toady, puts on a feast for his fellow mutants and the main course is a naked woman in a large platter of lettuce. Moments like that were censored entirely. It was a little over the top, but hey, it was supposed to be that kind of outrageous cult movie.

Blake Harris: Roller Blade? Randall Frakes: Yes, Roller Blade, a strange, improvised conception about roller-skating nuns with healing powers trying to bring order and love back to a ravaged, brutal world. Don had also previously made a wrestling documentary called I Like To Hurt People with Andre the Giant. New World Pictures—after Corman sold it to a bunch of clueless investors—had made over a million dollars with that documentary, so they picked up Roller Blade and made a small fortune on that as well. As a result, Don was the darling boy at New World, and they asked him the question everyone struggling to get in the business wants to hear: What else you got, kid?Blake Harris: Frogtown?Randall Frakes: Well, he didn't have anything except a one-page menu list of characters and situations for a movie that, yes, he was already calling Hell Comes to Frogtown. So he takes me to a restaurant, buys me enchiladas and tells me he's been thinking about my rants about the importance of script. At the restaurant, he shoves the one-pager in front of me and says that he needs a whole script fast. For New World.Blake Harris: I don't mean to interrupt you, but I'm curious what was even on that one-page document. How much had been thought out already?Randall Frakes: Not much. There was a short description of a place called Frogtown and some details about a main character was the only fertile male in a world where there were people who looked like frogs. That was all. But I looked at it and the whole movie—from beginning to end, pretty much the way the first draft was written—just started playing in my head. I looked at the one-pager in a sorta trance for about 15 minutes, until Don said, "Uh, your enchiladas are getting cold." And I hate cold enchilada. So that's when I turned to him and said I see the whole movie. I told him I could write it in a week or less, and then I scarfed down my lukewarm enchiladas.Blake Harris: And what did he say?Randall Frakes: He didn't believe me. But he told me if I did manage to write it in a week, he'd pay me a $500 bonus. To make sure I didn't somehow cheat, he sat alongside me while I typed the first draft of Hell Comes to Frogtown. It was pure stream of consciousness stuff—something I've never been able to repeat—and it resulted in a script 120 pages long.Blake Harris: How similar to the actual film was that first draft?Randall Frakes: [The draft] was a lot raunchier, which in my view was almost a Hallmark card post-apocalyptic movie! For example: In the beginning, when we first see Sam in his cell, he's masturbating. Just to show his absolute disdain for authority, his belief in living life to the fullest (no matter where you are) and also to introduce Sam as a "loaded pistol," always ready to fire. There was also a scene, later in the movie, where the Head Frog, Commander Toady, puts on a feast for his fellow mutants and the main course is a naked woman in a large platter of lettuce. Moments like that were censored entirely. It was a little over the top, but hey, it was supposed to be that kind of outrageous cult movie. Part 4: Wanted, Captured Blake Harris: So, degrees of raunchiness aside, you guys now had a full script. Was it something New World was interested in making?Randall Frakes: The president of New World at that time was Robert Rehme, the famed producer of many excellent action films (and also the president of the Academy Awards). Intrigued, he takes the script home and lets his wife read it, and she tells him it is a hilarious send-up of Mad Max and the Planet of the Apes movies. The next day, he calls Don and I into his office. There was good news and bad news.Blake Harris: What was the bad news?Randall Frakes: So the plan was for this to be a straight-to-video movie—with a budget of $300,000—that Don would direct and I would produce. But the bad news is that Rehme is assigning us a codirector and a coproducer.Blake Harris: And the good?Randall Frakes: The good news was he was upping the budget by a factor of 10 and planning on releasing the movie to a thousand theaters. Whoa! After a tough negotiation, Don and I ended up signing a pay-or-play deal, with each of us getting nearly $100,000. Not bad for out first studio deal. But signing that deal—because it was pay-or-play—meant that we didn't really have any contractual power and could be fired on a whim if they felt like it. So we lost creative control at that point. We didn't intend to, but we sold out. Oh well. I tried my best to prevent compromises and budgetary decisions that hurt the movie, and mostly failed.Blake Harris: How so?Randall Frakes: For example: Don and I had signed up a stuntman who built a motorcycle designed to flip and roll and always land back upright. This was to be used in the opening action scene where we see government forces capturing Sam. For budgetary reasons, New World did not want to film this scene, opting instead for a lame graphic: a WANTED poster for Sam Hell, followed by red letters stamped over it reading "Captured." Freaking lame. I tell Cameron about this and he's furious. He authorizes me to tell them that he will give the production $100,000 to film our opening chase. New World balked and refused to accept him as an investor, even when he promised to do a cameo in the movie and offered his name as a copresenter with New World. And by this time in Jim's career [following The Terminator and Aliens], that would have been a big boost to the movie. New World was just dumb. I'm sure they had their reasons, but they were bogus.Blake Harris: Having lost creative control, what was the dynamic like between Don and the codirector they assigned: R.J. Kizer?Randall Frakes: Don was basically reduced to a second unit director, though he got some really great shots. He was a tiger on set, but the main director [Kizer]—a sound effects cutter before and after Frogtown—was slow as molasses and didn't "get" the tone of the script. To Kizer's credit, he was not a stupid person, and this goofy movie was not the one he wanted to be his first major feature. He was brought in, basically, as insurance (against Don's lack of experience), and he did wind up directing several other B-movies.

Part 4: Wanted, Captured Blake Harris: So, degrees of raunchiness aside, you guys now had a full script. Was it something New World was interested in making?Randall Frakes: The president of New World at that time was Robert Rehme, the famed producer of many excellent action films (and also the president of the Academy Awards). Intrigued, he takes the script home and lets his wife read it, and she tells him it is a hilarious send-up of Mad Max and the Planet of the Apes movies. The next day, he calls Don and I into his office. There was good news and bad news.Blake Harris: What was the bad news?Randall Frakes: So the plan was for this to be a straight-to-video movie—with a budget of $300,000—that Don would direct and I would produce. But the bad news is that Rehme is assigning us a codirector and a coproducer.Blake Harris: And the good?Randall Frakes: The good news was he was upping the budget by a factor of 10 and planning on releasing the movie to a thousand theaters. Whoa! After a tough negotiation, Don and I ended up signing a pay-or-play deal, with each of us getting nearly $100,000. Not bad for out first studio deal. But signing that deal—because it was pay-or-play—meant that we didn't really have any contractual power and could be fired on a whim if they felt like it. So we lost creative control at that point. We didn't intend to, but we sold out. Oh well. I tried my best to prevent compromises and budgetary decisions that hurt the movie, and mostly failed.Blake Harris: How so?Randall Frakes: For example: Don and I had signed up a stuntman who built a motorcycle designed to flip and roll and always land back upright. This was to be used in the opening action scene where we see government forces capturing Sam. For budgetary reasons, New World did not want to film this scene, opting instead for a lame graphic: a WANTED poster for Sam Hell, followed by red letters stamped over it reading "Captured." Freaking lame. I tell Cameron about this and he's furious. He authorizes me to tell them that he will give the production $100,000 to film our opening chase. New World balked and refused to accept him as an investor, even when he promised to do a cameo in the movie and offered his name as a copresenter with New World. And by this time in Jim's career [following The Terminator and Aliens], that would have been a big boost to the movie. New World was just dumb. I'm sure they had their reasons, but they were bogus.Blake Harris: Having lost creative control, what was the dynamic like between Don and the codirector they assigned: R.J. Kizer?Randall Frakes: Don was basically reduced to a second unit director, though he got some really great shots. He was a tiger on set, but the main director [Kizer]—a sound effects cutter before and after Frogtown—was slow as molasses and didn't "get" the tone of the script. To Kizer's credit, he was not a stupid person, and this goofy movie was not the one he wanted to be his first major feature. He was brought in, basically, as insurance (against Don's lack of experience), and he did wind up directing several other B-movies.

My only real complaint is that Kizer was not enthusiastic about his shot to direct. Directing any movie requires total commitment and all your energy and imagination. And he seemed to be giving half. But maybe that was all he had to give. It could have been worse, I now realize, so I have to appreciate the effort he mounted. And I wouldn't have wanted to direct that movie.

Blake Harris: [laughing] And how did "Rowdy" Roddy Piper get targeted to star in the film? Was it hard to get him for the project?Randall Frakes: Generally speaking, it is not difficult to get any actor (star or not) to do any role—even the most stupid ones—if you simply offer them enough money. The history of cinema proves this over and over again.Blake Harris: Ha. True.Randall Frakes: Rowdy was not my choice. I wrote the Sam Hell part to be played by a motormouth comedian like Tim Thomerson. Someone with the wry, dry delivery of a Jack Nicholson. A smartass. An unlikely action hero. But the idea at New World was to put a wrestler in the main role because I Like To Hurt People had done so well for them. So, because of New World's wrestler fetish, they wanted a wrestler. Rowdy wanted to be a movie star and get out of beating on—or getting beat on by—Hulk Hogan.Blake Harris: Did you find his performance to be as bad as you'd feared?Randall Frakes: Well, the first time I see him, I think: Oh god, that's the doom of the movie. The guy's a mushmouth, he can barely speak He won't be able to say the dialogue! But like Schwarzenegger in True Lies [a film Frakes helped write], he rose to the challenge. He got an acting coach and took the assignment super-seriously. He turned out to be charming in the role. And he got better and better the more he worked. I do have to give the other director, Mr. Sound Editing Molasses, credit for patiently working with Roddy Piper to get the performance he did. He was not a bad choice for Sam Hell, as it turned out. He was not perfect, but close to it. I miss him and wished he could have stuck around for the Frogtown remake. But, as Kurt Vonnegut was fond of saying, so it goes...

Blake Harris: [laughing] And how did "Rowdy" Roddy Piper get targeted to star in the film? Was it hard to get him for the project?Randall Frakes: Generally speaking, it is not difficult to get any actor (star or not) to do any role—even the most stupid ones—if you simply offer them enough money. The history of cinema proves this over and over again.Blake Harris: Ha. True.Randall Frakes: Rowdy was not my choice. I wrote the Sam Hell part to be played by a motormouth comedian like Tim Thomerson. Someone with the wry, dry delivery of a Jack Nicholson. A smartass. An unlikely action hero. But the idea at New World was to put a wrestler in the main role because I Like To Hurt People had done so well for them. So, because of New World's wrestler fetish, they wanted a wrestler. Rowdy wanted to be a movie star and get out of beating on—or getting beat on by—Hulk Hogan.Blake Harris: Did you find his performance to be as bad as you'd feared?Randall Frakes: Well, the first time I see him, I think: Oh god, that's the doom of the movie. The guy's a mushmouth, he can barely speak He won't be able to say the dialogue! But like Schwarzenegger in True Lies [a film Frakes helped write], he rose to the challenge. He got an acting coach and took the assignment super-seriously. He turned out to be charming in the role. And he got better and better the more he worked. I do have to give the other director, Mr. Sound Editing Molasses, credit for patiently working with Roddy Piper to get the performance he did. He was not a bad choice for Sam Hell, as it turned out. He was not perfect, but close to it. I miss him and wished he could have stuck around for the Frogtown remake. But, as Kurt Vonnegut was fond of saying, so it goes... Part 5: So It Goes...Blake Harris: Given the creative differences on Hell Comes to Frogtown, what did you think of the final cut?Randall Frakes: The first and only time I ever saw the movie with an audience—prior to a couple of months ago—was on the old MGM lot in Culver City. The Cary Grant screening room. The audience was made up of the crew and some of the cast, and the movie dropped like a 10-ton stone into mud. I hated the movie. Hated it. Looking at it was like staring at a wrecked career. My friend William Wisher—who I mentioned earlier, and who was amazed my dopey script even got made—came up to me afterward and said, "I'm sorry they screwed up your movie, Randy." That was the nail in the coffin.Blake Harris: Damn...Randall Frakes: But I must also say that a few months ago, when the Cinefamily Theater here in L.A. did a one-night Rowdy Roddy Piper memorial screening of They Live and Hell Comes to Frogtown, the audience seemed to get all the jokes as intended. They were extremely appreciative and enthusiastic in their response. So, despite all the ruinous stuff that happened to compromise Frogtown, it evidently still hits the mark well enough for some people who like weird and funny stuff to enjoy. For that, I am grateful. And producing that movie was a huge learning experience (mostly about what not to do!), an on-the-job training that has helped me navigate this silly business and the people who presume to run it.Blake Harris: Well, before we finish, let's try and take the business out of movies for moment. At the heart of almost everything you've said—be it articles in the Army, co-inventing Xenogenesis, bringing Hell to Frogtown or anything else—is story. Everyone knows that story is important, but learning the craft is a tricky thing. So I was wondering —for a young screenwriter or filmmaker out there—how you might suggest they learn about and hone the craft of storytelling?Randall Frakes: Based on watching James Cameron craft his scripts (and sometimes crafting them with him), I would say to use his two credos: One, good enough isn't, and two, break new ground. And I would add that placing your story in an unusual and amazing locale helps. But more than any of those things, the real key is conflict. You must have personifications of conflicting ideas that have universal resonance. A conflict that will be gripping to almost every person on this planet. There are several sub-strategies that help you do this. A compelling main character who the audience loves and bonds with intensely. Even better is the biggest, baddest, most clever villain you can think of. A good villain makes for a good movie, because it generates intense conflict. Two worlds must be in collision. And those two worlds must be personified in characters. Not just abstractions.Blake Harris: What do you mean?Randall Frakes: For example: In Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, Romeo represents romantic love in the extreme. Juliet represents an innocent beauty to be loved. Their speeches and actions are models of the attitudes, emotions and themes that they represent. Tybalt hates. Mercutio is reason and humor, which turn out not to be effective weapons against hate, which is kept going by the long family feud between the Capulets and the Montagues. So, if the premise of that play is "love overcomes hate"—which it is, since in the final scene both families have put aside their hatred to bury their children whose love for each other is a shame on their parents' petty hate—then every single character must represent one side of the equation or the other. A story without this clash of ideas personified in its characters is going to bore the pants off of Hollywood readers and producers. An even more obvious example is Jim's Terminator. Sarah Connor is pregnant in the last part of the movie. She is a pregnant woman (life) fighting to defeat the cyborg killer (implacable death). Life defeats death, essentially, when Sarah smashes the killer machine in a metal press. She terminates death. She is creative woman, with the power of new life in her belly. This is called "unity of opposites." It is an organic way to make sure there is intense enough conflict in your story.Blake Harris: That's great, Randy. Thank you.Randall Frakes: The only other advice I can give is keep it fast, keep it simple—by which I mean keep each scene simple, though the overall effect can be complex—and keep it relatively short. Them's my two cents.

Part 5: So It Goes...Blake Harris: Given the creative differences on Hell Comes to Frogtown, what did you think of the final cut?Randall Frakes: The first and only time I ever saw the movie with an audience—prior to a couple of months ago—was on the old MGM lot in Culver City. The Cary Grant screening room. The audience was made up of the crew and some of the cast, and the movie dropped like a 10-ton stone into mud. I hated the movie. Hated it. Looking at it was like staring at a wrecked career. My friend William Wisher—who I mentioned earlier, and who was amazed my dopey script even got made—came up to me afterward and said, "I'm sorry they screwed up your movie, Randy." That was the nail in the coffin.Blake Harris: Damn...Randall Frakes: But I must also say that a few months ago, when the Cinefamily Theater here in L.A. did a one-night Rowdy Roddy Piper memorial screening of They Live and Hell Comes to Frogtown, the audience seemed to get all the jokes as intended. They were extremely appreciative and enthusiastic in their response. So, despite all the ruinous stuff that happened to compromise Frogtown, it evidently still hits the mark well enough for some people who like weird and funny stuff to enjoy. For that, I am grateful. And producing that movie was a huge learning experience (mostly about what not to do!), an on-the-job training that has helped me navigate this silly business and the people who presume to run it.Blake Harris: Well, before we finish, let's try and take the business out of movies for moment. At the heart of almost everything you've said—be it articles in the Army, co-inventing Xenogenesis, bringing Hell to Frogtown or anything else—is story. Everyone knows that story is important, but learning the craft is a tricky thing. So I was wondering —for a young screenwriter or filmmaker out there—how you might suggest they learn about and hone the craft of storytelling?Randall Frakes: Based on watching James Cameron craft his scripts (and sometimes crafting them with him), I would say to use his two credos: One, good enough isn't, and two, break new ground. And I would add that placing your story in an unusual and amazing locale helps. But more than any of those things, the real key is conflict. You must have personifications of conflicting ideas that have universal resonance. A conflict that will be gripping to almost every person on this planet. There are several sub-strategies that help you do this. A compelling main character who the audience loves and bonds with intensely. Even better is the biggest, baddest, most clever villain you can think of. A good villain makes for a good movie, because it generates intense conflict. Two worlds must be in collision. And those two worlds must be personified in characters. Not just abstractions.Blake Harris: What do you mean?Randall Frakes: For example: In Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, Romeo represents romantic love in the extreme. Juliet represents an innocent beauty to be loved. Their speeches and actions are models of the attitudes, emotions and themes that they represent. Tybalt hates. Mercutio is reason and humor, which turn out not to be effective weapons against hate, which is kept going by the long family feud between the Capulets and the Montagues. So, if the premise of that play is "love overcomes hate"—which it is, since in the final scene both families have put aside their hatred to bury their children whose love for each other is a shame on their parents' petty hate—then every single character must represent one side of the equation or the other. A story without this clash of ideas personified in its characters is going to bore the pants off of Hollywood readers and producers. An even more obvious example is Jim's Terminator. Sarah Connor is pregnant in the last part of the movie. She is a pregnant woman (life) fighting to defeat the cyborg killer (implacable death). Life defeats death, essentially, when Sarah smashes the killer machine in a metal press. She terminates death. She is creative woman, with the power of new life in her belly. This is called "unity of opposites." It is an organic way to make sure there is intense enough conflict in your story.Blake Harris: That's great, Randy. Thank you.Randall Frakes: The only other advice I can give is keep it fast, keep it simple—by which I mean keep each scene simple, though the overall effect can be complex—and keep it relatively short. Them's my two cents.