How Did This Get Made: Death Spa (An Oral History)

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Haunted House – House + Spa = How Did This Get Made?!?!

Nobody sets out to make a bad movie. But the truth is, it happens all the time. And every time it does, there's a fun misadventure and cautionary tale lurking somewhere behind the scenes. This is that story for the campy, cultish 1989 horror film Death Spa.

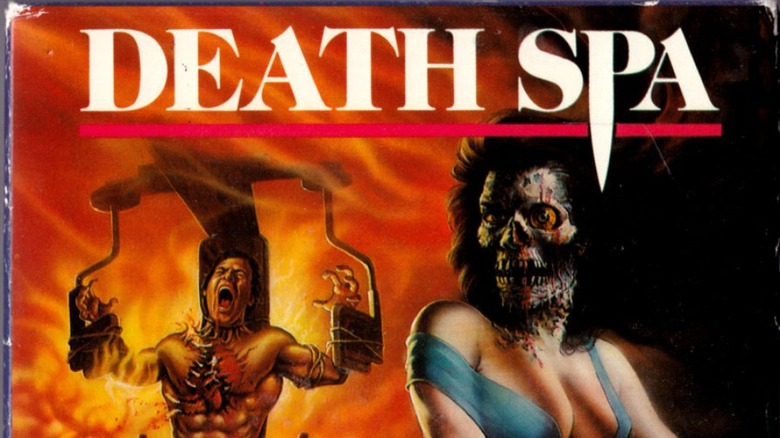

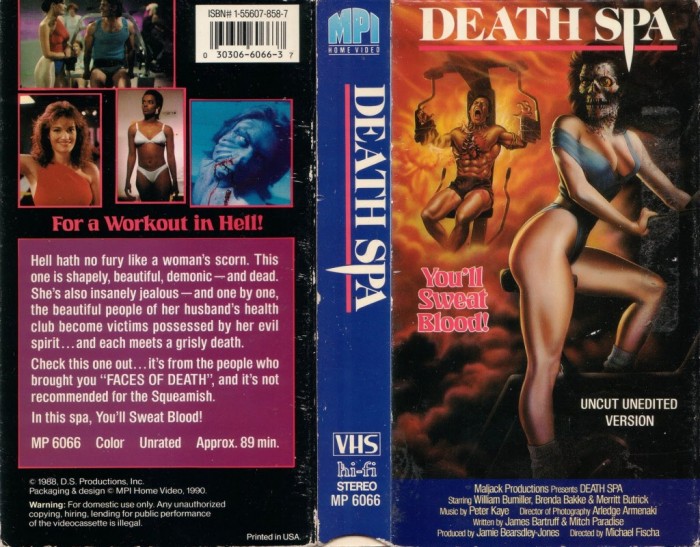

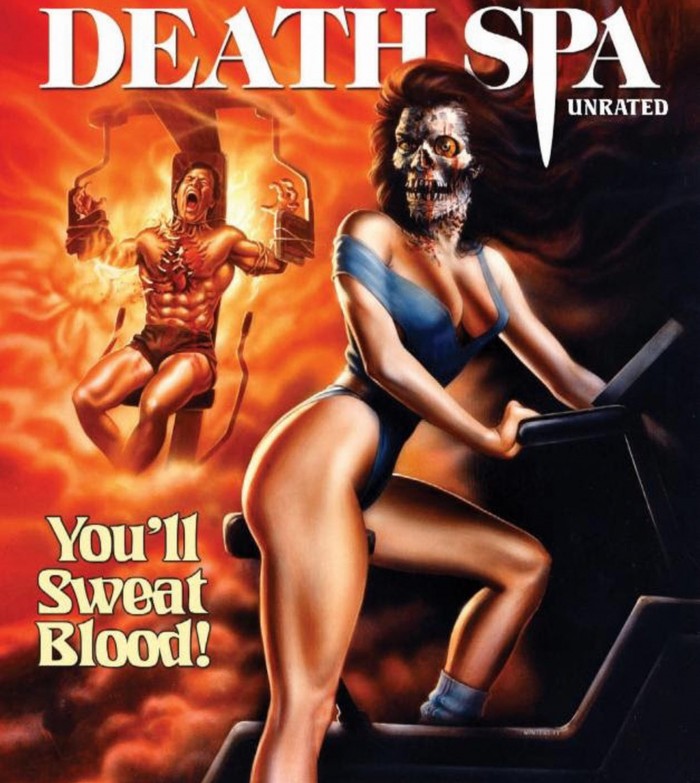

How Did This Get Made is a companion to the podcast How Did This Get Made with Paul Scheer, Jason Mantzoukas and June Diane Raphael which focuses on movies so bad they are amazing. This regular feature is written by Blake J. Harris, who you might know as the writer of the book Console Wars, soon to be a motion picture produced by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg. You can listen to the Death Spa edition of the HDTGM podcast here. Synopsis: When an electrical storm hits a computerized health club, the machines seemingly come to life and start murdering the fitness junkies inside.Tagline: You'll Sweat Blood!

To celebrate Halloween, me and the gang at HDTGM decided to throw on our neon 1980's headbands and investigate what happens when good gymnasiums go bad.

Here's what happened, as told by those who made it happen...

Featuring:

PrologueIn 2007, Elijah Drenner received a list of little known horror films whose home video rights had been acquired, but not yet released, by a distributor named MPI Media. This list, and what it represented, was of particular interest to Drenner. Not only because, as a cinephile and horror enthusiast, he was in the small fraternity of people who had actually heard of these movies before. But also because, over the past few years, he'd been crafting making-of documentaries to accompany many of MPI's DVD releases. Elijah Drenner: I did this sort of work for a couple of labels under the MPI umbrella: Dark Sky Films and Gorgon Media. Gorgon was almost exclusively their Faces of Death stuff and Dark Sky used to be catalogue horror titles. But then after Hatchet 2 they started producing contemporary stuff. Like The Innkeepers and a new one called Deathgasm.Even though MPI was mainly focused on new content, they did still own the rights to a strange and expansive roster of older horror films. So they kept Drenner abreast with the state of their library in order to pick his brain about what might be worthy of a re-release and, in that event, whether it might add value for him to create a making-of. Elijah Drenner: I love doing these kinds of documentaries. You always learn something interesting, so I'm always eager to do more. And I remember, back in 2007, asking MPI what else they got. They sent me a list of this and this and this. Some were good some were bad. But also on this list was something called Death Spa. Huh? Death Spa? What the hell was that? I mean, no one had ever heard of this thing before....

PrologueIn 2007, Elijah Drenner received a list of little known horror films whose home video rights had been acquired, but not yet released, by a distributor named MPI Media. This list, and what it represented, was of particular interest to Drenner. Not only because, as a cinephile and horror enthusiast, he was in the small fraternity of people who had actually heard of these movies before. But also because, over the past few years, he'd been crafting making-of documentaries to accompany many of MPI's DVD releases. Elijah Drenner: I did this sort of work for a couple of labels under the MPI umbrella: Dark Sky Films and Gorgon Media. Gorgon was almost exclusively their Faces of Death stuff and Dark Sky used to be catalogue horror titles. But then after Hatchet 2 they started producing contemporary stuff. Like The Innkeepers and a new one called Deathgasm.Even though MPI was mainly focused on new content, they did still own the rights to a strange and expansive roster of older horror films. So they kept Drenner abreast with the state of their library in order to pick his brain about what might be worthy of a re-release and, in that event, whether it might add value for him to create a making-of. Elijah Drenner: I love doing these kinds of documentaries. You always learn something interesting, so I'm always eager to do more. And I remember, back in 2007, asking MPI what else they got. They sent me a list of this and this and this. Some were good some were bad. But also on this list was something called Death Spa. Huh? Death Spa? What the hell was that? I mean, no one had ever heard of this thing before....

CUT TO: 26 YEARS EARLIER...

Part 1: Woman on FireEvery movie—good or bad, big or small—is the byproduct of several individuals. That number, of course, can range from a few dozen to a few thousand, but regardless of the final tally there's one thing almost every movie has in common: a prime mover. The person who sets it all into motion and pushes everything along until the bitter (or beautiful) end. This is the person who, without them, the movie would not exist nor get finished. And in the case of Death Spa, that prime mover is Jamie Beardsley. Jamie Beardsley: Would I still have made the movie if I'd known, from the beginning, how hard it was all going to be? Oh yes, absolutely. I was so down for doing this. I was just a woman on fire. I would have done it if it was twice as hard. I just really wanted to get out there and get some shit done. I mean, we knew it wasn't going to be the greatest film in the world, but we just wanted to make something different and something cool.The "we" that Beardsley is referring to—a renegade-spirited cast and crew that would grow to over sixty by the time that Death Spa was all said and done—started off as just two people: her and Walter Shenson. Jamie Beardsley: The way I met Walter was kind of funny. I was living in LA and working with a financier named Bill Sharmat who was one of the engineers of the Australian and US tax shelter deals of the late 70s and early 80s. Things were going pretty well, until Bill decided he wanted to move to Australia. But luckily, before he left, he gave me a list of people who I could contact to see about scrounging up a job. And on that list, of about ten people, Walter happened to be one of those names and we just kind of struck up an incredible friendship that, you know, lasted until the day he died.

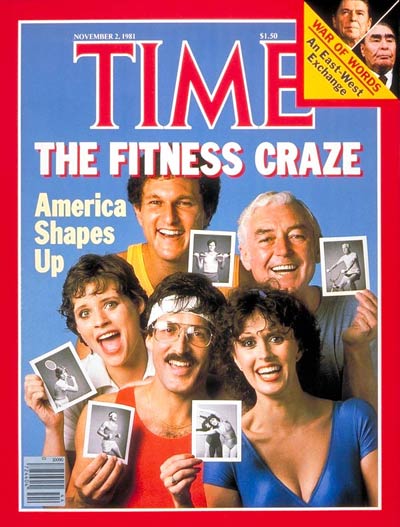

Walter Shenson was a seasoned producer who, by the time he met Beardsley, was 61 years old and hadn't made a film in over four years. But still, there was something magnetic and mysterious about him. Jamie Beardsley: Walter really was one of the last gentleman producers. Always wore a suit, always was nicely dressed and groomed. Very cultured. Very, very creative. And he just loved movies. He was a complete and total enthusiast. And so together, we set about making some movies together.Not long into their collaboration, a producer friend named Waleed Ali—who worked at MPI Media and had distributed several of Shenson's films—mentioned that the horror market was really hot and that they should consider doing a project in this space. Although neither Beardsley nor Shenson had any experience in the horror genre, they were both intrigued by the challenge and the financial upside of doing a low budget, self-contained scary movie. So too was a young, Austrian theater director. Michael Fischa: [thick Austrian accent] My first thing in America, I did a play called It's Not The End of the World or Is It? at the Beverly Hills Playhouse. And then Universal came in and bought the rights; they wanted to do a TV show and the whole blah blah. I thought this would be a good way to get into the film scene, so to speak, but I was new to Hollywood and Universal did not want anything to do with me. Then I met Walter.Jamie Beardsley: Walter just loved Michael. Right away. Walter was always very good at finding talented, new voices.Michael Fischa: I always did serious theater stuff, but I said to Walter I really wanted to do a horror movie. He said, "You know what? I did the Beatles movies and all those other movies, but I really want to do a silly horror movie too." That was the beginning! But I did not have a horror movie written and he did not either, so Jamie Beardsley, who was the producer, hired a writer. Beardsley brought on James Bartruff, a writer with no prior credits, to script a horror movie that captured the trendy zeitgeist of Los Angeles in the early eighties. Michael Fischa: The health craze had blossomed in LA. They came up like mushrooms. So quickly that they went out of business. So we thought, basically, we turn it around and we have a ghost in our health club. That could be a fun scenario.And so, with close collaboration from Beardsley, Shenson and Fischa, James Bartruff got to work writing Death Spa. But even though Bartruff managed finish a draft of the script by early 1983, nothing happened with project for another few years. There were two primary reasons for this delay:

Beardsley brought on James Bartruff, a writer with no prior credits, to script a horror movie that captured the trendy zeitgeist of Los Angeles in the early eighties. Michael Fischa: The health craze had blossomed in LA. They came up like mushrooms. So quickly that they went out of business. So we thought, basically, we turn it around and we have a ghost in our health club. That could be a fun scenario.And so, with close collaboration from Beardsley, Shenson and Fischa, James Bartruff got to work writing Death Spa. But even though Bartruff managed finish a draft of the script by early 1983, nothing happened with project for another few years. There were two primary reasons for this delay:

The first reason, with time, would eventually resolve itself. But the second, that would require the wordsmithery of one Mr. Mitch Paradise...  Part 2: A Hard Day's NightMitch Paradise: I was writing spec screenplays in San Francisco and I got recommended to her for this project. And we met and she gave me a copy of the script, which was really rather a pedestrian attempt...I mean, the idea of the haunted health club was there. But it really was something else. It was not very good. James Bartroff, I guess, was the original writer. Never met him. Never have met him. Don't even know if he's still around. But he's listed as the co-writer on Death Spa, which is something of a gift, by the way, in all honesty. I probably could have made that "written by Mitch Paradise" from a story by both of us. Because it was a total re-write. I totally re-concepted the thing.Michael Fischa: Story is so important. A good horror move has to have a story. Girls getting butchered in a room for two hours is not enough. Even if it's totally absurd and silly, you need a story to get into it and get entertainment out of it.Mitch Paradise: I felt it needed something a little twisted. So I came up with this idea that it's a computer-run club. And that the ghost was in the machine, basically. So I came up with the idea that all the machines were computer run. That you didn't, like, move weights around yourself. That was...I think I was the first guy to ever do that. I mean, there are clubs like that now. And then I came up with the idea that the owner's dead wife was a twin of the guy who runs the computer, you know, command station in the basement for the club. And so she was possessing, alternately, him and a female. So that was really the concept of all of that. So, I re-concepted it, re-wrote it, they liked it and they shot it.Jamie Beardsley: Actually, I don't know that Mitch even knows this. But one of the juicy, juicy tidbits...you probably know who Kirk Honeycutt is, right? So Mitch's draft was good, almost there. But he's the one that did the final polish on the script that got us to greenlight. And just to avoid having everyone and the kitchen sink's name on there, Mickey and I took our names off the script and let Jim and Mitch be the only ones with their names on it. And, you know, I don't think that Kirk wanted to be credited, per se, at that time.Mitch Paradise: For me, I was just thinking I was getting a shot here to write something and get paid for it. And I liked the people, so I was happy to do it. It was a fun project. I really liked Walter a lot and Jamie was a sweetheart. They seemed to like what I was doing and, when it was ready to go, they made it right here in Los Angeles.David Shaughnessy: [in a deep-voiced British accent] At a health spa, I believe, on the corner of Crescent and Sunset. Though I must confess that, at the time, I wasn't particularly familiar with the city. Nor did I really have much of an idea about what I was getting into with Death Spa.Shaughnessy had moved to the United States only a couple months prior to filming. And although, indeed, he did not know what he was getting into, he wouldn't have cared anyway because this was all just a means to an end.David Shaughnessy: My father knew Walter Shenson really well from England. So Walter basically gave me a job just so I could get my SAG card. And it was just the most bizarre thing. And I had no idea what the story was—I could never really follow the story—I'm not even sure if there was one. But it didn't matter anyway, because I was doing it—yes, of course, for the SAG card, but also for the chance to work with Walter. I mean, he wasn't just a producer; he was something of a legend.Mitch Paradise: Walter Shenson is a great man. Literally, a great man. The scion of a family of deli owners in San Francisco. There's a well-known Jewish delicatessen called Shensons out on Geary and 14th. Been there forever. But he sort of ran away from the deli business and went down to Hollywood and got involved in the movie business. And he was a publicist at Paramount when he went to England and discovered Dudley Moore and made Dudley Moore's first movie. Left Paramount, went out on his own. Made a lot of great films: The Mouse that Roared, 30 Is a Dangerous Age, Reuben, Reuben.Jamie Beardsley: And of course, you must know what he's most famous for?Mitch Paradise: Took a chance on this rock and roll band that people in America didn't think would amount to much—they're called The Beatles—and he was able to retain the rights to the movies. His estate now owns Help and A Hard Day's Night. That's crazy.David Shaughnessy: You want a piece of Beatles stuff? I don't know if it's true, but I was having lunch with Walter one day and he told me that years earlier—when they were shooting A Hard Days Night at L Street Studios in London—he was having lunch with John Lennon after a very long night of shooting. At that point, they still didn't have a title for the movie and, what's worse, they didn't have a title song. But apparently, at some point in the conversation, John recounted how the previous night they hadn't finished until 4 or so in the morning. And he mentioned that Ringo—who was always saying these weird malapropisms, weird phrases—had commented in the morning that, "Yeah, that was a Hard Day's Night." And Walter, mid-conversation, said "Oh my god! That's the title!" So he got John and Paul together and he told them to go off that night, after they were done shooting, he told them to go home and come up with a song called A Hard Day's Night. So they went off to Paul's apartment that night, and then the next day John called up Walter and said, "We need to see you right away." And Walter, at this point, thought: oh god, they're going to be in another fight, aren't they? Because John and Paul were always fighting about stuff. But what could he do? So Walter went to John's dressing room, where they had this little gold box of Benson and Hedges cigarettes. And on it, they had written down all the lyrics to their new song. And just as Walter is starting to read whatever it was they had written, John and Paul burst out into song. [doing his best Beatles impression]: IT'S BEEN A HARD DAY'S NIGHT...AND I'VE BEEN WORKING LIKE A DOG...Jamie: He just had a million stories and he wanted to tell them all to me. I felt so lucky. And those stories he would tell me, they just gave me an appreciation of great storytelling. The importance of talking about something. Not, you know, all about the effects and the guns and the sex and the whatever. Walter just was, he was amazing. He was amazing. He was kind of a father figure to me as well because I lost my father very young. He actually gave me away at my wedding.David Shaughnessy: Given that Walter had done so many great projects, yes, it did strike me as a bit odd that he'd be doing Death Spa. But, you know, I think at that point he was kind of semi-retired. And I think he kind just wanted to do something that was young and hip. He was very into wanting to stay hip and relevant, so I think that was why he wanted to do it. And, around this time, horror movies were the thing.

Part 2: A Hard Day's NightMitch Paradise: I was writing spec screenplays in San Francisco and I got recommended to her for this project. And we met and she gave me a copy of the script, which was really rather a pedestrian attempt...I mean, the idea of the haunted health club was there. But it really was something else. It was not very good. James Bartroff, I guess, was the original writer. Never met him. Never have met him. Don't even know if he's still around. But he's listed as the co-writer on Death Spa, which is something of a gift, by the way, in all honesty. I probably could have made that "written by Mitch Paradise" from a story by both of us. Because it was a total re-write. I totally re-concepted the thing.Michael Fischa: Story is so important. A good horror move has to have a story. Girls getting butchered in a room for two hours is not enough. Even if it's totally absurd and silly, you need a story to get into it and get entertainment out of it.Mitch Paradise: I felt it needed something a little twisted. So I came up with this idea that it's a computer-run club. And that the ghost was in the machine, basically. So I came up with the idea that all the machines were computer run. That you didn't, like, move weights around yourself. That was...I think I was the first guy to ever do that. I mean, there are clubs like that now. And then I came up with the idea that the owner's dead wife was a twin of the guy who runs the computer, you know, command station in the basement for the club. And so she was possessing, alternately, him and a female. So that was really the concept of all of that. So, I re-concepted it, re-wrote it, they liked it and they shot it.Jamie Beardsley: Actually, I don't know that Mitch even knows this. But one of the juicy, juicy tidbits...you probably know who Kirk Honeycutt is, right? So Mitch's draft was good, almost there. But he's the one that did the final polish on the script that got us to greenlight. And just to avoid having everyone and the kitchen sink's name on there, Mickey and I took our names off the script and let Jim and Mitch be the only ones with their names on it. And, you know, I don't think that Kirk wanted to be credited, per se, at that time.Mitch Paradise: For me, I was just thinking I was getting a shot here to write something and get paid for it. And I liked the people, so I was happy to do it. It was a fun project. I really liked Walter a lot and Jamie was a sweetheart. They seemed to like what I was doing and, when it was ready to go, they made it right here in Los Angeles.David Shaughnessy: [in a deep-voiced British accent] At a health spa, I believe, on the corner of Crescent and Sunset. Though I must confess that, at the time, I wasn't particularly familiar with the city. Nor did I really have much of an idea about what I was getting into with Death Spa.Shaughnessy had moved to the United States only a couple months prior to filming. And although, indeed, he did not know what he was getting into, he wouldn't have cared anyway because this was all just a means to an end.David Shaughnessy: My father knew Walter Shenson really well from England. So Walter basically gave me a job just so I could get my SAG card. And it was just the most bizarre thing. And I had no idea what the story was—I could never really follow the story—I'm not even sure if there was one. But it didn't matter anyway, because I was doing it—yes, of course, for the SAG card, but also for the chance to work with Walter. I mean, he wasn't just a producer; he was something of a legend.Mitch Paradise: Walter Shenson is a great man. Literally, a great man. The scion of a family of deli owners in San Francisco. There's a well-known Jewish delicatessen called Shensons out on Geary and 14th. Been there forever. But he sort of ran away from the deli business and went down to Hollywood and got involved in the movie business. And he was a publicist at Paramount when he went to England and discovered Dudley Moore and made Dudley Moore's first movie. Left Paramount, went out on his own. Made a lot of great films: The Mouse that Roared, 30 Is a Dangerous Age, Reuben, Reuben.Jamie Beardsley: And of course, you must know what he's most famous for?Mitch Paradise: Took a chance on this rock and roll band that people in America didn't think would amount to much—they're called The Beatles—and he was able to retain the rights to the movies. His estate now owns Help and A Hard Day's Night. That's crazy.David Shaughnessy: You want a piece of Beatles stuff? I don't know if it's true, but I was having lunch with Walter one day and he told me that years earlier—when they were shooting A Hard Days Night at L Street Studios in London—he was having lunch with John Lennon after a very long night of shooting. At that point, they still didn't have a title for the movie and, what's worse, they didn't have a title song. But apparently, at some point in the conversation, John recounted how the previous night they hadn't finished until 4 or so in the morning. And he mentioned that Ringo—who was always saying these weird malapropisms, weird phrases—had commented in the morning that, "Yeah, that was a Hard Day's Night." And Walter, mid-conversation, said "Oh my god! That's the title!" So he got John and Paul together and he told them to go off that night, after they were done shooting, he told them to go home and come up with a song called A Hard Day's Night. So they went off to Paul's apartment that night, and then the next day John called up Walter and said, "We need to see you right away." And Walter, at this point, thought: oh god, they're going to be in another fight, aren't they? Because John and Paul were always fighting about stuff. But what could he do? So Walter went to John's dressing room, where they had this little gold box of Benson and Hedges cigarettes. And on it, they had written down all the lyrics to their new song. And just as Walter is starting to read whatever it was they had written, John and Paul burst out into song. [doing his best Beatles impression]: IT'S BEEN A HARD DAY'S NIGHT...AND I'VE BEEN WORKING LIKE A DOG...Jamie: He just had a million stories and he wanted to tell them all to me. I felt so lucky. And those stories he would tell me, they just gave me an appreciation of great storytelling. The importance of talking about something. Not, you know, all about the effects and the guns and the sex and the whatever. Walter just was, he was amazing. He was amazing. He was kind of a father figure to me as well because I lost my father very young. He actually gave me away at my wedding.David Shaughnessy: Given that Walter had done so many great projects, yes, it did strike me as a bit odd that he'd be doing Death Spa. But, you know, I think at that point he was kind of semi-retired. And I think he kind just wanted to do something that was young and hip. He was very into wanting to stay hip and relevant, so I think that was why he wanted to do it. And, around this time, horror movies were the thing.

Jamie Beardsley: What? Time was a luxury we didn't have!Michael Fischa: Time, I think, was the biggest challenge on Death Spa. It is the biggest challenge on every movie. To manage the time right because you always want more. You always want one more day. To get it all done on time before the money runs out.Arledge Armenaki: But even though the film had a relatively small budget [$750,000] we were still able to do a lot of cool things. Like the opening scene.Michael Fischa: The opening scene, maybe, was my favorite part of the film. Because it was very elaborate.Jamie Beardsley: And it was cool. There was a style to it. It was the perfect way to bring viewers into the world that we were making.Arledge Armenaki: The shot starts off on the Marlboro Man, which was a very famous poster on Sunset Boulevard for many, many, many years. This big, giant, iconic poster.Michael Fischa: We had a crane and a steadicam operator on a crane, up 60 feet.Arledge Armenaki: We had to get a construction crane in there because conventional cranes couldn't get the height that we needed to be. And then we had to weld out a portion of basket so our camera operator fit inside. Liz Zeigler. Who, I believe at the time, was the only female steadicam operator in LA at the time. I called her the "Amazon Woman" because she was such a tall gal and very chesty. [chuckles] She had to have a special breastplate made for her steadicam, which totally thrilled the crew. But anyway, the shot starts up there on the Marlboro man and then it cranes down and you see the sign for the health club. Night time, it's raining. And then a lightening bolt—which we did with an optical flash—goes off and all of the sudden the sign goes kazonkers. The light dims on some of the letters in the sign and, all of the sudden STAR BODY HEALTH SPA becomes... STAR BODY HEALTH SPA.Michael Fischa: And then crane went down and she stepped off the platform and we went handheld through the whole spa.Arledge Armenaki: Which was a huge challenge, to do all that in one shot.Michael Fischa: One mistake, we had to start all over again.Arledge Armenaki: When Liz Zeigler was lowered on the crane the grips stabilized it by holding the crane basket and putting Apple box steps out so she could smoothly step out of a big construction crane basket down to the ground. So we had to rehearse all the lightening cues with the rain, the sign, the door opening—the exact movements of everything—so that she can glide into the health club and go into that dance room in one fluid shot. And you have to remember that, during all of this, I'm looking over the steadicam's shoulder and following her as close as I can without getting in the way. And there's no playback, you know? It's film.Jamie Beardsley: Have you ever carried a film canister, by the way? You can't believe how heavy they are. I mean they are so flippin' heavy I mean, it was crazy how heavy and how physical—very, very, physical—it all was.Arledge Armenaki: So we didn't have all the super extras that a major motion picture would have. We were an independent film. But we had just what we needed to get the job done.And they did. Not just with the opening shot, but with the entire production. It was never easy, nor particularly pretty, but the film managed to finish on time and on budget. But, unfortunately, that's when things got really difficult.

Part 4: In Which Women on Fire are Burnt OutJamie Beardsley: What were my expectations for the film when we finished shooting? Hmmm....that's a good question. I guess the first I should say is that even when you're "done," you're never really done. After production ended, I heard that they wanted to do re-shoots. I was like what? Okay, well what is it? They just needed some bits and bobs.Michael Fischa: You always sit there afterwards and say, "I should have done that, I should have done that." Whatever it is. You always think what you could have done different. Sometimes there is money to do such things, but usually there is not. So you're never really happy with the film. Which is not the right attitude, of course, but it is the truth.Jamie Beardsley: And then even after you have all the shots you need, or at least know all the shots that you're going to have, the editing can just be...by the way, we ended up editing the whole thing in Michael's living room. [referring to editor Michael Kewley]. That's what we could afford. So, you know, it just...those were the days, my friend.Mitch Paradise: I sat with Walter in the editing bay, once, when we went over it. You know, suggested a change or two. But I was not really involved in the production or editing part. I was the writer, I got paid, and I took my credit such as it was. And off it went. I think it went straight to video. I don't think it ever had a feature release.Jamie Beardsley: I thought for sure we would...well, back then, you sold your movie. And we did. We actually did. It wasn't a lot. I think we made like $350,000 was our advance. But I guess I was hoping to have a little more of a homerun, you know?Arledge Armenaki: It's a tough business. It's a tough, tough business.Jamie Beardsley: If not a homerun, I at least kind of expected that we would hit it somewhere. Get to third base, or something.Michael Fischa: I don't know about the financial outcome of the whole thing. But, I mean, it must have done something or they would not have re-release it.David Shaughnessy: I don't even think Death Spa went to movie theaters. Did it?Elijah Drenner: I think Death Spa had a limited theatrical run in the United States. A small theatrical screening probably just to satisfy SAG requirements and that was it. And then it played theatrically in Europe as a movie called Witch Bitch.Jamie Beardsley: Looking back, I don't know, sometimes I blame myself for not being better at making a deal. Like really selling the film. And well, you know, I must say that...by the end of it all...I kind of lost steam. By the end of making a film like this...you're just dead. You're done, you're cooked, you're over, it's finished. You're like: oh my god, I never want to see this film or any of these people again in my whole life. You know? After a while you just run screaming from the room. And yeah, it was a rough. So I don't know that I fought for it as much as I should have. You know? I mean, I wasn't the only person, but I don't think I did very well in that part of the movie. And I kind of, I don't know, I kind of feel sad and kind of blame myself a bit now that you mention it. Thanks! Now I'm all depressed.

Part 5: Midnight MadnessAfter watching Elijah Drenner's An Exercise in Terror: The Making of Death Spa—his 51 minute documentary included on the film's 2014 Blu-Ray release—I sent an e-mail to the director. In addition to letting him know how much I enjoyed his short film, I also asked him a question: Did he think that MPI ever would have re-released Death Spa if not for his pushing them to do so?

Jamie Beardsley: What? Time was a luxury we didn't have!Michael Fischa: Time, I think, was the biggest challenge on Death Spa. It is the biggest challenge on every movie. To manage the time right because you always want more. You always want one more day. To get it all done on time before the money runs out.Arledge Armenaki: But even though the film had a relatively small budget [$750,000] we were still able to do a lot of cool things. Like the opening scene.Michael Fischa: The opening scene, maybe, was my favorite part of the film. Because it was very elaborate.Jamie Beardsley: And it was cool. There was a style to it. It was the perfect way to bring viewers into the world that we were making.Arledge Armenaki: The shot starts off on the Marlboro Man, which was a very famous poster on Sunset Boulevard for many, many, many years. This big, giant, iconic poster.Michael Fischa: We had a crane and a steadicam operator on a crane, up 60 feet.Arledge Armenaki: We had to get a construction crane in there because conventional cranes couldn't get the height that we needed to be. And then we had to weld out a portion of basket so our camera operator fit inside. Liz Zeigler. Who, I believe at the time, was the only female steadicam operator in LA at the time. I called her the "Amazon Woman" because she was such a tall gal and very chesty. [chuckles] She had to have a special breastplate made for her steadicam, which totally thrilled the crew. But anyway, the shot starts up there on the Marlboro man and then it cranes down and you see the sign for the health club. Night time, it's raining. And then a lightening bolt—which we did with an optical flash—goes off and all of the sudden the sign goes kazonkers. The light dims on some of the letters in the sign and, all of the sudden STAR BODY HEALTH SPA becomes... STAR BODY HEALTH SPA.Michael Fischa: And then crane went down and she stepped off the platform and we went handheld through the whole spa.Arledge Armenaki: Which was a huge challenge, to do all that in one shot.Michael Fischa: One mistake, we had to start all over again.Arledge Armenaki: When Liz Zeigler was lowered on the crane the grips stabilized it by holding the crane basket and putting Apple box steps out so she could smoothly step out of a big construction crane basket down to the ground. So we had to rehearse all the lightening cues with the rain, the sign, the door opening—the exact movements of everything—so that she can glide into the health club and go into that dance room in one fluid shot. And you have to remember that, during all of this, I'm looking over the steadicam's shoulder and following her as close as I can without getting in the way. And there's no playback, you know? It's film.Jamie Beardsley: Have you ever carried a film canister, by the way? You can't believe how heavy they are. I mean they are so flippin' heavy I mean, it was crazy how heavy and how physical—very, very, physical—it all was.Arledge Armenaki: So we didn't have all the super extras that a major motion picture would have. We were an independent film. But we had just what we needed to get the job done.And they did. Not just with the opening shot, but with the entire production. It was never easy, nor particularly pretty, but the film managed to finish on time and on budget. But, unfortunately, that's when things got really difficult.

Part 4: In Which Women on Fire are Burnt OutJamie Beardsley: What were my expectations for the film when we finished shooting? Hmmm....that's a good question. I guess the first I should say is that even when you're "done," you're never really done. After production ended, I heard that they wanted to do re-shoots. I was like what? Okay, well what is it? They just needed some bits and bobs.Michael Fischa: You always sit there afterwards and say, "I should have done that, I should have done that." Whatever it is. You always think what you could have done different. Sometimes there is money to do such things, but usually there is not. So you're never really happy with the film. Which is not the right attitude, of course, but it is the truth.Jamie Beardsley: And then even after you have all the shots you need, or at least know all the shots that you're going to have, the editing can just be...by the way, we ended up editing the whole thing in Michael's living room. [referring to editor Michael Kewley]. That's what we could afford. So, you know, it just...those were the days, my friend.Mitch Paradise: I sat with Walter in the editing bay, once, when we went over it. You know, suggested a change or two. But I was not really involved in the production or editing part. I was the writer, I got paid, and I took my credit such as it was. And off it went. I think it went straight to video. I don't think it ever had a feature release.Jamie Beardsley: I thought for sure we would...well, back then, you sold your movie. And we did. We actually did. It wasn't a lot. I think we made like $350,000 was our advance. But I guess I was hoping to have a little more of a homerun, you know?Arledge Armenaki: It's a tough business. It's a tough, tough business.Jamie Beardsley: If not a homerun, I at least kind of expected that we would hit it somewhere. Get to third base, or something.Michael Fischa: I don't know about the financial outcome of the whole thing. But, I mean, it must have done something or they would not have re-release it.David Shaughnessy: I don't even think Death Spa went to movie theaters. Did it?Elijah Drenner: I think Death Spa had a limited theatrical run in the United States. A small theatrical screening probably just to satisfy SAG requirements and that was it. And then it played theatrically in Europe as a movie called Witch Bitch.Jamie Beardsley: Looking back, I don't know, sometimes I blame myself for not being better at making a deal. Like really selling the film. And well, you know, I must say that...by the end of it all...I kind of lost steam. By the end of making a film like this...you're just dead. You're done, you're cooked, you're over, it's finished. You're like: oh my god, I never want to see this film or any of these people again in my whole life. You know? After a while you just run screaming from the room. And yeah, it was a rough. So I don't know that I fought for it as much as I should have. You know? I mean, I wasn't the only person, but I don't think I did very well in that part of the movie. And I kind of, I don't know, I kind of feel sad and kind of blame myself a bit now that you mention it. Thanks! Now I'm all depressed.

Part 5: Midnight MadnessAfter watching Elijah Drenner's An Exercise in Terror: The Making of Death Spa—his 51 minute documentary included on the film's 2014 Blu-Ray release—I sent an e-mail to the director. In addition to letting him know how much I enjoyed his short film, I also asked him a question: Did he think that MPI ever would have re-released Death Spa if not for his pushing them to do so?

From: elijah drenner

Date: Wed, Oct 28, 2015 at 12:57 AM

Subject: Re: hey

To: Blake Harris

Hey Blake -

Glad you liked it the making-of.

I did pester Todd Wieneke at MPI to release DEATH SPA over the course of at least 5 years. I can't say it was my idea, since it was an asset that I'm sure they fully intended to exploit, it was just a matter of how and when. But yes, I would say that I was an outside force that nudged Todd, to nudge his bosses. I know Todd wanted it back out there, but the higher-ups perhaps didn't consider it in the same class as their other titles. He was able to get a budget for proper restoration, scan the elements (thats a whole other story) and ensure the new presentation was top-notch.

I'd say that it was a joint effort between the two of us.

Personally, I think that Elijah's being modest. But, based on the short time that I've known him, I wouldn't expect any less. I first reached out to him a couple weeks ago when starting on this piece and, it should be noted, he was incredibly helpful throughout.

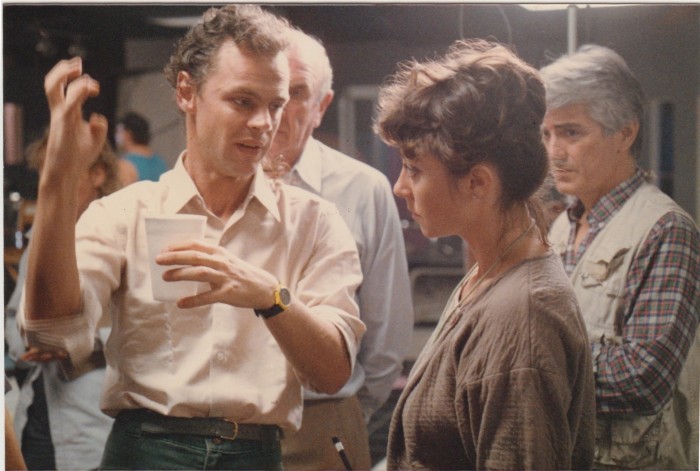

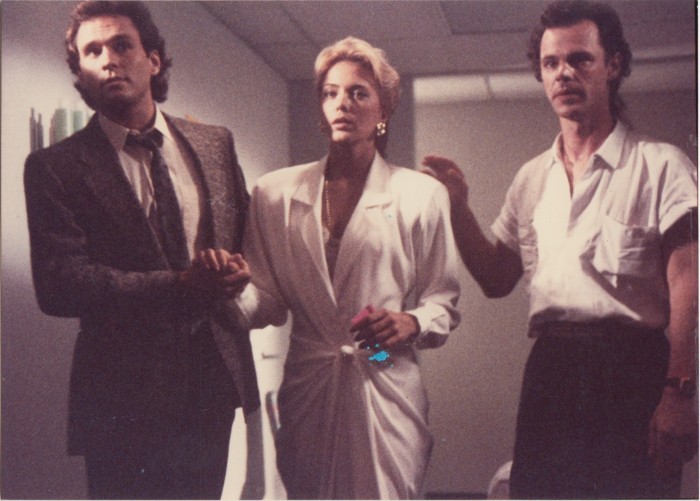

Jamie Beardsley on the right and editor Michael Kewley's wife on the left (there cameo is discovering the exploading woman in the bathroom)

If you're interested in learning more about this film, check out Elijah Drenner's An Exercise in Terror: The Making of Death Spa. In addition, I highly recommend one of Drenner's new films: That Guy Dick Miller, which chronicles the life and career of a great character actor whose career spanned over six decades and nearly 200 films.Or, if you're more interested in making films than watching them, you may want to consider the film program at Western Carolina University where Arledge Armenaki serves as an Associate Producer of Cinematography.

If you're interested in learning more about this film, check out Elijah Drenner's An Exercise in Terror: The Making of Death Spa. In addition, I highly recommend one of Drenner's new films: That Guy Dick Miller, which chronicles the life and career of a great character actor whose career spanned over six decades and nearly 200 films.Or, if you're more interested in making films than watching them, you may want to consider the film program at Western Carolina University where Arledge Armenaki serves as an Associate Producer of Cinematography.