What It Was Like To Film Eyes Wide Shut, Stanley Kubrick's Final Masterpiece [Exclusive Interview]

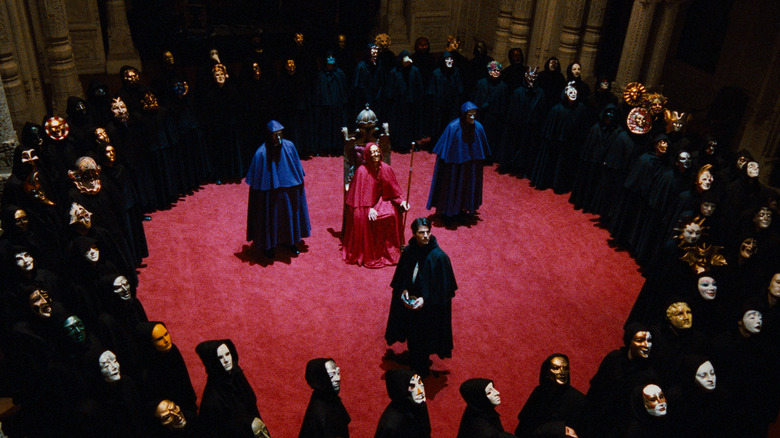

In 1999, Stanley Kubrick's "Eyes Wide Shut" arrived surrounding a wave of buzz and hype for various reasons. One was that the film's subject matter was kept highly secretive — all anyone knew was that sex played a big part in the story. Another was that the film featured married stars Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman playing the leads. But the biggest element that piqued people's curiosity was the fact that Kubrick had died after shooting the film and supposedly before he could deliver his final cut.

Already a legendary filmmaker at the time, Kubrick's death created an air of morbid curiosity about "Eyes Wide Shut." But when critics and audiences started to see the film, the reaction was mixed. In the years since, however, "Eyes Wide Shut" has rightly taken its place as one of Kubrick's best films. But an air of mythology still surrounds the pic, primarily thanks to insinuations that the cut that hit theaters was not the cut Kubrick would've preferred. The filmmaker was notorious for tinkering with his movies up to, and even after, release. So there was a sort of understanding that had Kubrick lived, he most likely would've kept working on "Eyes Wide Shut."

Kubrick may be gone, but someone who worked closely with him on the film, cinematographer Larry Smith, has just overseen a new 4K restoration of "Eyes Wide Shut" for the Criterion Collection. Smith worked with Kubrick on three films: he served as a gaffer on "Barry Lyndon" and "The Shining" before landing the cinematographer job on "Eyes Wide Shut." I was able to speak with Smith about what it was like working with Kubrick, creating the distinct lighting style of "Eyes Wide Shut," and what's been changed for the Criterion release.

Note: This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Working with Stanley Kubrick

At this point, Stanley Kubrick has this sort of mythical status surrounding him, but you really worked with him. You worked with him for several years: You were a gaffer on "Barry Lyndon" and "The Shining," and then of course you did "Eyes Wide Shut." So I wonder if you could just tell me a little bit about what it was like really working with this guy who's become this legend.

Well, of course when I first met him, which as you rightly say, was on "Barry Lyndon," I didn't know then — I was quite a young technician, early twenties. I mean, I knew about him, but I didn't know about him. You know what I mean? Sometimes you know about people, but you don't really know. You just hear some stuff and the work that he's done, but you don't really know too much about him. And that was the case for me. It took a while, because Stanley always spoke to a very few people on the set. The links in the chain were always quite short, because he didn't want to waste his time going through various people, which was one of the reasons that I didn't really speak to him that much in the early days of "Barry Lyndon." We said good morning. But in terms of conversation, there wasn't much of that between he and I.

And then at some point during the filming of "Barry Lyndon," the gaffer, who was a friend of mine, had some problems and he didn't come into work one particular day or a couple of days, whenever it was. So because it was just [Kubrick] and I literally on the set all of the time and everybody else was kind of outside, apart from actors, I kind of got dragged into it. He had to speak to me and we had to communicate. Then from there on in, of course, we knew each other.

So that was my introduction, working with him. But what I did realize was that even though I didn't know that much about him, when I first ever set eyes on him, when he first came onto the set as he pulled up in his car and I was looking, doing something near a window, and I saw him get out of the car with his assistant. Even though I couldn't hear what was being said — I was maybe 50 feet away — you could see the reaction of the people. We were in a big stately home, so it was a lot of crew, and you didn't need a lot of words there because you could see this respect that people had for him. So I kind of took that on board. And this was, as I say, way before I got to talk to him.

So I knew there was something here. I knew there was this aura around him, that people that knew much more about him than me had. When I got to the stage where I was speaking to him more, [a] few months had gone by, so I'd seen him working the way he worked, which was very, very different to any other film set that I'd been on at that time. The way that he tested everything, he used to use a Polaroid camera in those days where he would do various, or get John Alcott, who [was the Director of Photography on "Barry Lyndon"], to do various exposures on the Polaroid camera in black and white — a professional Polaroid camera, by the way. We'd look at all of those and put them all in a book and then decide what the shooting stop was going to be for this next take. It may change the take after because of the light that was coming through the windows in this big stately home.

I'd never really seen anything like that before. To be honest, I didn't really understand it, what it was he was doing, because when I looked at the book, when we had the various exposures in, I could see very little if any change, from my eye at that time. So that was kind of fascinating to me, what he was seeing within this Polaroid still that nobody else probably could see. He would say, "That's the one, that's the stop. We're going to shoot at that."

Creating the look of Eyes Wide Shut

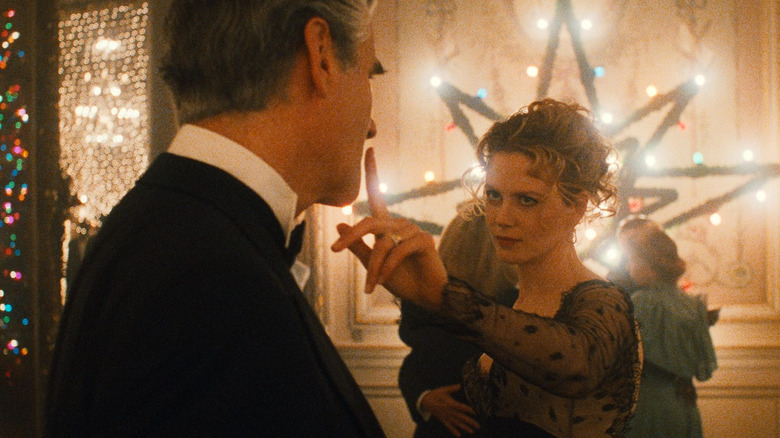

Kubrick had a reputation for being very meticulous. What did he tell you he wanted for "Eyes Wide Shut"? It has a very distinct look. It has a lot of blues, a lot of gold. It has all those Christmas lights. Was this part of the conversation? How did that come about — the look of the film?

I'm not saying that there wasn't a master plan at some stage in the planning and the prep, but Stanley was the kind of director who liked to let things evolve. So during the prep, during the set build and when we would do lighting tests, we just had a vision of ... okay, let's just say the opening scene in "Eyes Wide Shut," Tom's apartment. We knew it was Christmas in New York. It was night. We use practicals all the time, so they're going to be warm. So that was the premise for that set. It was night, interior, warm. So then we started testing things like, "Okay, so what are we going to see outside?" And in those days we were using translights to get the cityscape of New York ... So we get that, we test that. I [didn't] want them to be too bright, overtaking the scene ... so should we have anything coming through the windows? ... So I was like, "Well, we can. I've been playing around with a few color balance schemes, like lots of warm light and lots of blue light, and I [want to] show you something." He said, "Yeah, show me something. Give me a call when you're ready," which I did.

I had one big tungsten light for each window, and I added lots of color correction blue on it, but I put more blue on it than I would normally. I knew it was more of a theatrical look, but I just wanted to show him that. Then my plan was to take a layer off and another layer off to get back to what would be a more realistic blue light coming through the window, or a white light, even. Anyway, he came onto the set and he saw this blue light and he said, "It's very blue." When I explained to him what I was going to do, he said, "Well, I dunno. I like it. It's kind of interesting." And that was what happened on that first scene. We just happened to come across something in the early stages of testing that he liked. I already liked it anyway, but I just thought it was probably a bit theatrical. But he immediately grasped that, and we kind of ran with that literally for the rest of the movie.

Restoring (and altering) Eyes Wide Shut for the Criterion release

This new Criterion release, it has a new restoration, which you oversaw. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about what changed, or what do you think is different about this version than the theatrical cut? I watched the Blu-ray and it does look a little different. So I'm wondering what you focused on. What are the key differences?

Well ... the film grade. I don't know, in Stanley's career as a filmmaker, if he ever allowed his film to be graded, color graded by anybody else but him. I don't think it happened at all, but I'm not a hundred percent sure on that. It certainly didn't happen, I can say, from "Dr. Strangelove" all the way through "Eyes Wide Shut." So the tragedy of that was, that after he delivered the final cut, the film wasn't completely finished in terms of color grading. Well, it wasn't finished at all in terms of color grading, but we had a level of control over that already. Because again, unlike most other filmmakers, we used to give the labs our printer lights. So we knew what we were getting was what we were telling them that we wanted.

So you could arguably say the film was always going to be 70-odd-percent, 80% in the area that it should have been, but it wasn't finished, and it got finished by other people in the chaos after he died. I first saw the finished film at the premiere in L.A. and personally I wasn't too pleased with it, because they should have called me, and they should have gotten me in. Even though I was working on something else [at the time], I would've done something. So the film was never finished I would say definitely not to his standard, and certainly not the way I would've finished it. Now, fast forward to where we are now, and having the discussions with Criterion, they asked me what did I think about the look of the film? And I told them what my view was and they said, "Well, we think exactly the same thing."

So we then did a whole grading session based on how I felt it should be. And also, remember this: "Eyes Wide Shut," when we shot, it was all force-developed two stops, at a time when you don't have the post-production facilities that you have now. So there were things that weren't corrected. As an example, there's a scene in the overdose scene in the bathroom where when you track through the bathroom, there's a chrome strip, which is like a mirror. And my focus puller, my first [assistant cameraperson], was in that — and not just a glimpse; you could see who it was, it was a fairly slow track. That was never [fixed]. So things like that I was able to rectify.

The lengthy production of Eyes Wide Shut

Note: "Eyes Wide Shut" was in production for 400 days, making it the longest continuous film shoot on record.

This film is legendary for being so long to make. It took a long time to make this movie. Did it feel that way while you were making it? I understand that Kubrick's line of thinking, from what I've read, was, "Why would we rush this if we don't have to rush it?" Did it feel like that sort of set where it was just like, "We're going to get what we need to get"?

Well, obviously I had the luck of having [worked on] two other movies with him, so I knew Stanley's style. Stanley's philosophy is really, really simple: We spend all of this money building sets, getting [the] cast, preparing to get to this stage where we're going to shoot a movie. We've spent all of the money, so to speak. This is the cheapest part, in a way. We've bought ourselves time to make the kind of movie we want to make, or the kind of movie that he wanted to make. Did it seem long to me? Well, all of Stanley's movies seemed long to me when you are on them working. But when you know the system, when the format that he uses, it is what it is. This is how he works, and if it's just not for you, it's not for you.

Criterion's special edition 4K UHD and Blu-ray of "Eyes Wide Shut" will be available on November 25, 2025.