This Controversial Dustin Hoffman Movie Is Now Impossible To Watch Digitally

Has there ever been a more controversial year in cinema than 1971? It was the year that Ken Russell's "The Devils" caused outrage with its graphic sexuality and blasphemous imagery; elsewhere, Stanley Kubrick's "A Clockwork Orange" divided critics with its ugly violence upon making its debut in New York, while Ted Kotcheff's "Wake in Fright" turned stomachs with its grisly kangaroo hunt sequence. In the United States, the gloves were off after the Hays Code had given way to the more lenient MPAA ratings system in 1968, allowing filmmakers to explore challenging themes and show sex and violence in more explicit detail. Among the American movies that pushed these new boundaries were Don Siegel's "Dirty Harry" and Sam Peckinpah's "Straw Dogs," an intensely misanthropic psychodrama that became notorious for its depiction of sexual assault.

"Straw Dogs" was Peckinpah's first non-Western film, and it was an unusual hybrid, existing in a mostly uncharted hinterland between the burgeoning British folk horror scene (it was released the same year as "The Blood on Satan's Claw," itself part of folk horror's "Unholy Trinity") and the ferocious Wild West machismo that had made Bloody Sam infamous. It was also a means to an end for Peckinpah himself, who had recently been fired by Warner Bros. after the disastrous production of "The Ballad of Cable Hogue." With few options, the director headed to the southwest of England to make an adaptation of Gordon William's novel "The Siege of Trencher's Farm" — a book that Peckinpah deemed "lousy" apart from its climactic action set piece.

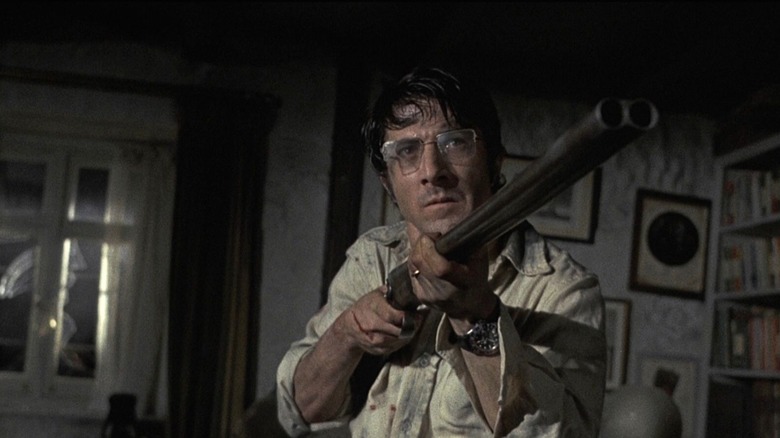

"Straw Dogs" stars Dustin Hoffman and Susan George as David and Amy Sumner, an ill-fitting young couple who move to Amy's home village in a remote corner of Cornwall. The local men resent one of their own marrying a meek American academic and tensions simmer as Amy's ex-boyfriend, Charlie Venner (Del Henney), and his roughneck friends are hired to work on the couple's home, culminating in a vicious attack on Amy and a subsequent last stand as the Sumners unwittingly harbor a sex offender. It proved so controversial in the UK that the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) only lifted a home video ban in 2002. Nowadays, the film is almost impossible to find, as it is currently unavailable on streaming platforms and physical media copies are few and far between. Let's take a closer look at Peckinpah's hugely contentious classic and how it holds up today.

Straw Dogs is notorious for its sexual violence

The disturbing sexual undercurrents of "Straw Dogs" are clear from the opening moments when we first meet Amy, parading confidently through the village in a short skirt and bra-less under her sweater. A younger village girl named Janice (Sally Thomsett) mimics her attitude and dress sense as the men folk look on with lust and disapproval — this is a remote rural community, and they haven't quite caught up with the latest trends in liberation for women. There is also the small matter of Henry Niles (David Warner), a despised local child molester who is only tolerated by the villagers because he's one of their own.

David is uncomfortable in the presence of the burly red-blooded types leering at Amy, passing his feelings of inadequacy onto his wife through belittling comments and blaming her for leading them on. She retaliates by petulantly flirting with Charlie and the other the workmen to spite him. After one of the men kills their cat to intimidate David further, Amy goads him into proving his masculinity and he accepts an invite to go hunting with the guys on the moors. But it turns out to be a ruse as Charlie heads back to the farm and forces himself on Amy, followed by a second and more brutal violation by his friend Scutt (Ken Hutchinson).

This sexual assault scene was controversial at the time and it is arguably even more problematic from a modern perspective. Although Amy tries to fend Charlie off and clearly says "no," she succumbs and appears to be enjoying the first assault by her ex. It's a harrowing scene that works in the context of the story's build-up of antagonism and micro-aggressions, but it comes across as extremely misogynistic because the film suggests Amy gets what she deserves and Peckinpah apparently couldn't agree more. Part of it may have been playing up to his reputation as a provocateur, but the filmmaker often peppered interviews with unbelievably offensive opinions about women and their role in sexual relationships. Discussing "Straw Dogs" with Playboy in 1972, he talked about the scene in terms of a sub-dom fantasy enjoyed by Amy and controversially stated that the second attack was the price she must pay for her "little game." Thanks to this attitude, it's not hard to see why the film still repulses and angers viewers to this day.

The violence in Straw Dogs is also hard-hitting

Straw Dogs" is also controversial for its strong violence, which fully explodes in the final siege at the farm. Things kick off as David and Amy attend an event at the church hall. Everyone is there, including Amy's attackers and the reviled Henry Niles. When David ignores the flirtatious advances of young Janice, the girl seeks attention by going off alone with Niles — something that the whole village knows is a Bad Idea. Sure enough, Niles accidentally kills her and flees the scene, but gets knocked over by David as the Sumners drive home. They then take the injured sex offender inside, and David phones the village doctor. However, his call also inadvertently leads a vigilante mob to their door.

The siege is an extended sequence of sustained tension as David uses his smarts to outwit, maim, and eventually kill the home invaders. While it isn't as splatter-y as the gruesome finale of "The Wild Bunch," it feels more intimidating due to the claustrophobic setting and prolonged brutality. More disturbing than the mob is David's behavior as he goes into caveman mode to defend his patch, literally dragging Amy by her hair at one point. One of Peckinpah's regular themes was exploring the violence inherent in society, and, like "Wake in Fright" and "Apocalypse Now" a few years later, the true horror is the primitivism lurking beneath the surface of the modern world and how quickly men regress to savagery.

Much like "The Wild Bunch," "Straw Dogs" is a blunt denouncement of violence from Peckinpah, who depicts it as something that debases everyone it touches. As the filmmaker told Playboy:

"You can't make violence real to audiences today without rubbing their noses in it. We watch our wars and see men die, really die, every day on television, but it doesn't seem real. We've been anesthetized by the media. What I do is show people what it's really like — not by showing it as it is so much as by heightening it, stylizing it."

The message is clear in the final scene when David drives Niles back to the village. The latter says he doesn't know his way home, and David replies that he doesn't, either. There is no way back to their old life for David or Susan after the events of the film. With "Straw Dogs" having come out while the Vietnam War was still ongoing, there was no way back for American society, either.